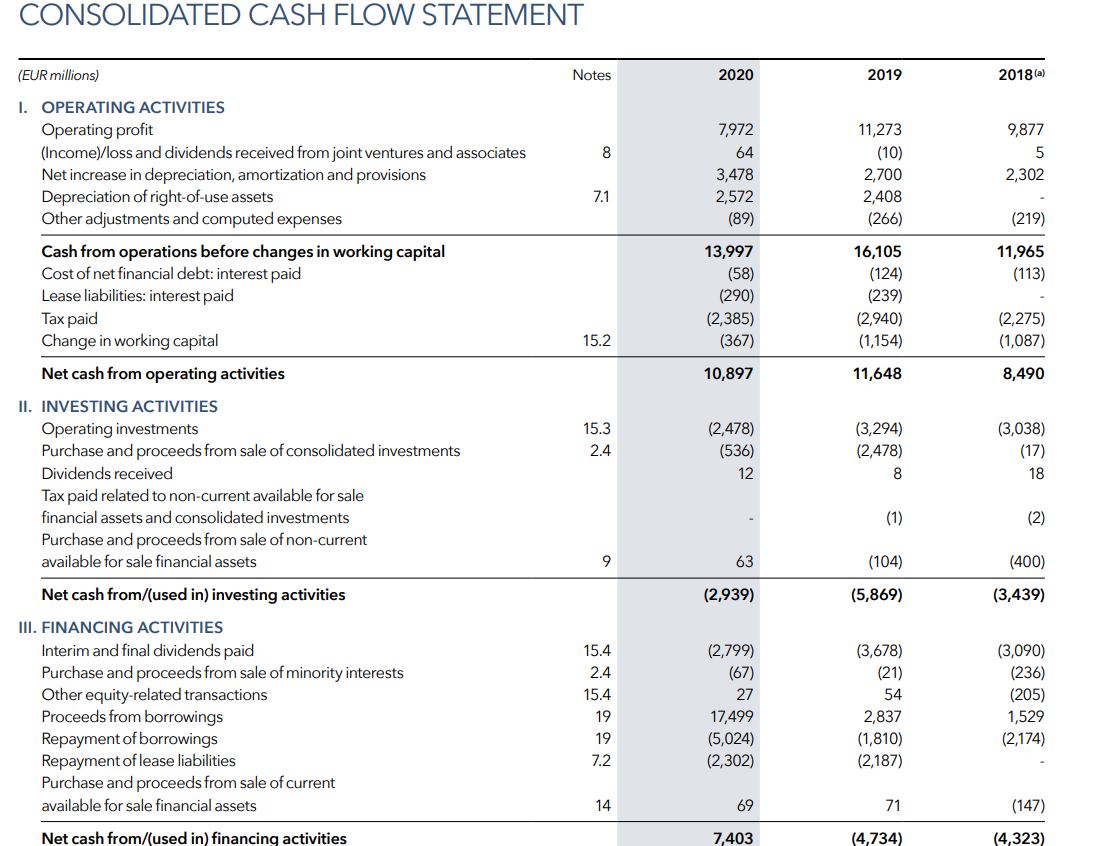

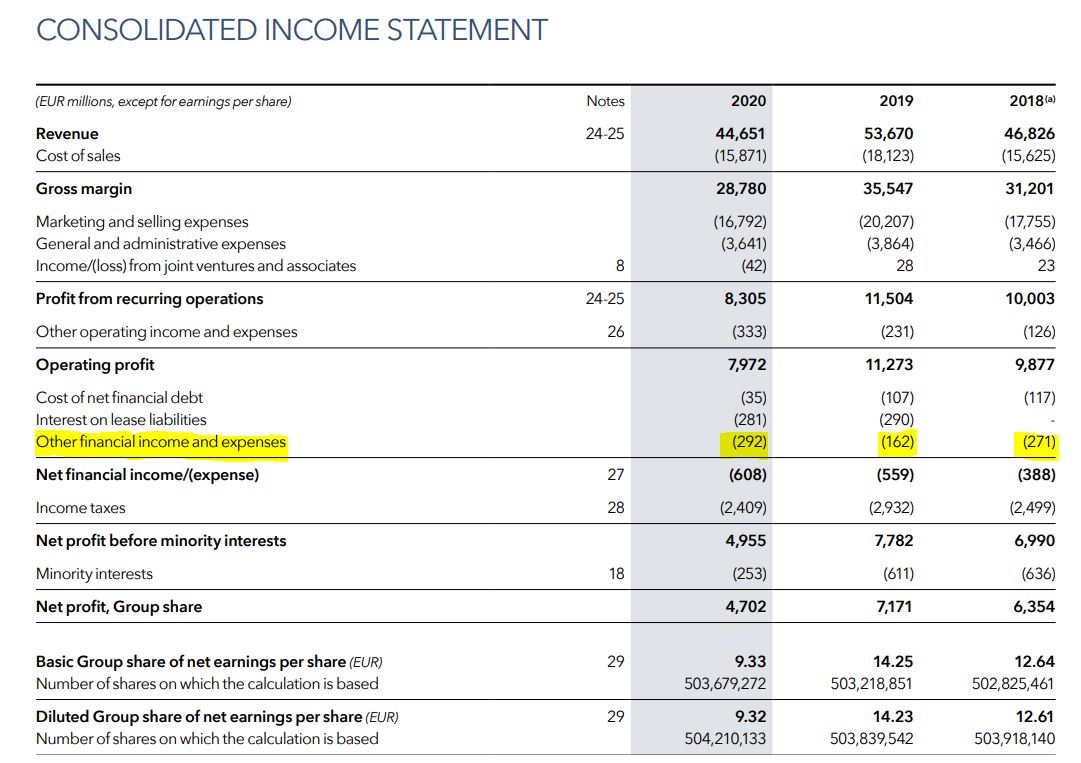

This article written by Akshit GUPTA (ESSEC Business School, Master in Management, 2019-2022) presents the technical subject of theta, an option Greek used in option pricing and hedging to deal with he passing of time.

Introduction

Theta is a type of option Greek which is used to compute the sensitivity or rate of change of the value of an option contract with respect to its time to maturity. The theta is denoted using the symbol (θ). Essentially, the theta is the first partial derivative of the price of the option contract with respect to the time to maturity of the option contract.

It is shown as:

Where V is the value of the option contract and T the time to maturity for the option contract.

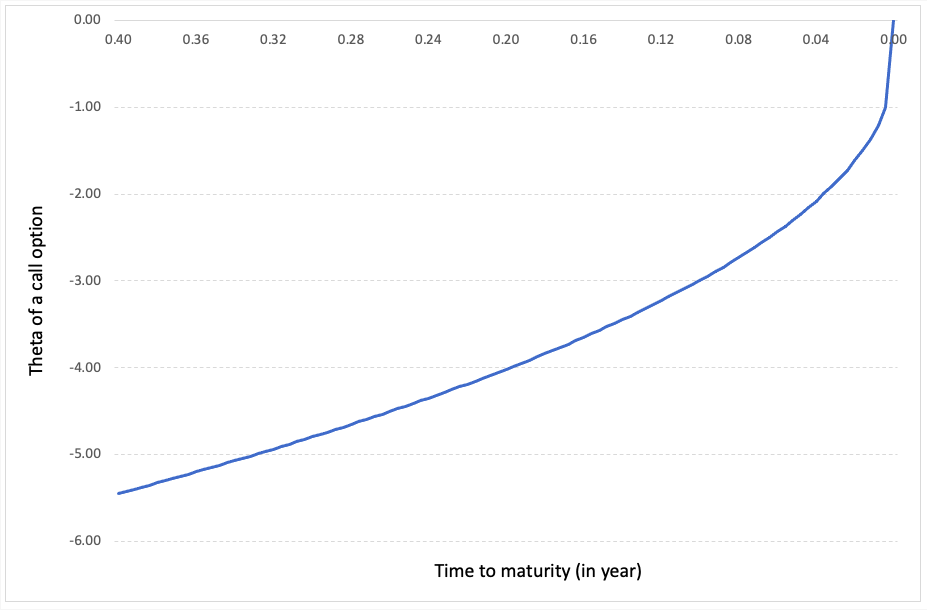

Theoretically, as the option contract approaches maturity, the theta of on option contract increases and moves towards zero as the time value or the time value of the option decreases. This is referred to as “theta decay”.

For example, an option contract is trading at a premium of $10 and has a theta of -0.8. Thus, with theta decay, the option price will decrease to $9.2 after one day and further to $6 after five days.

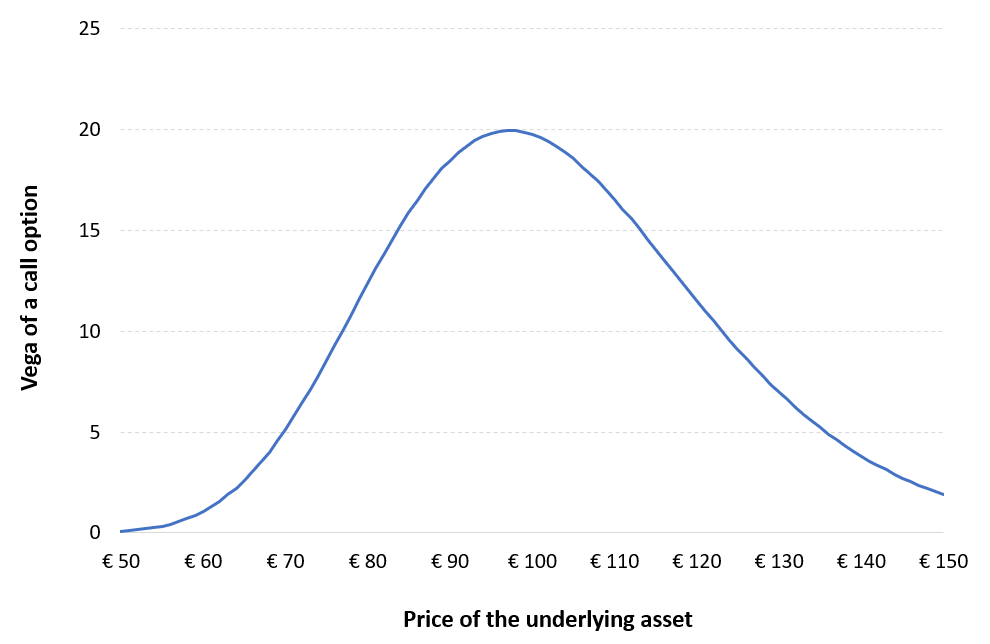

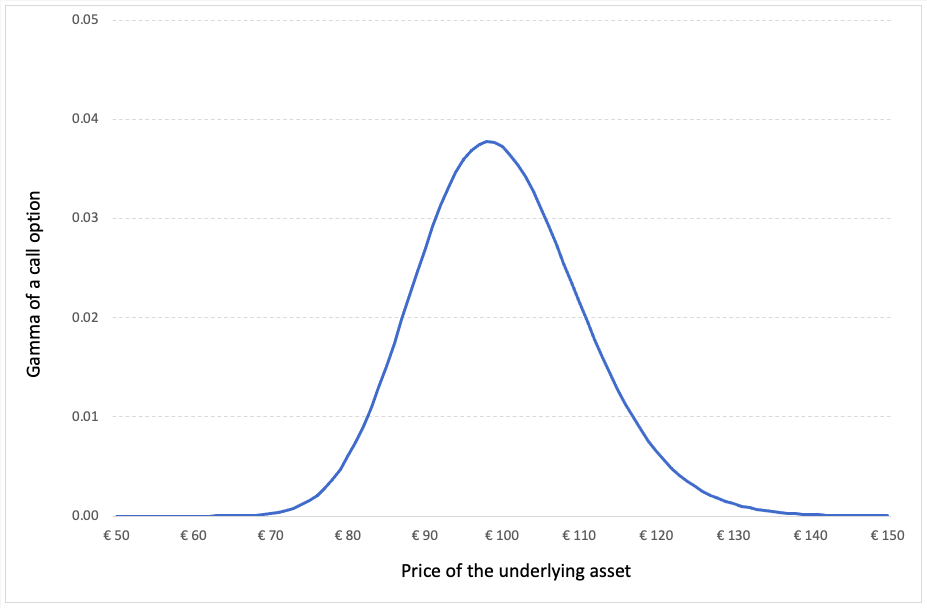

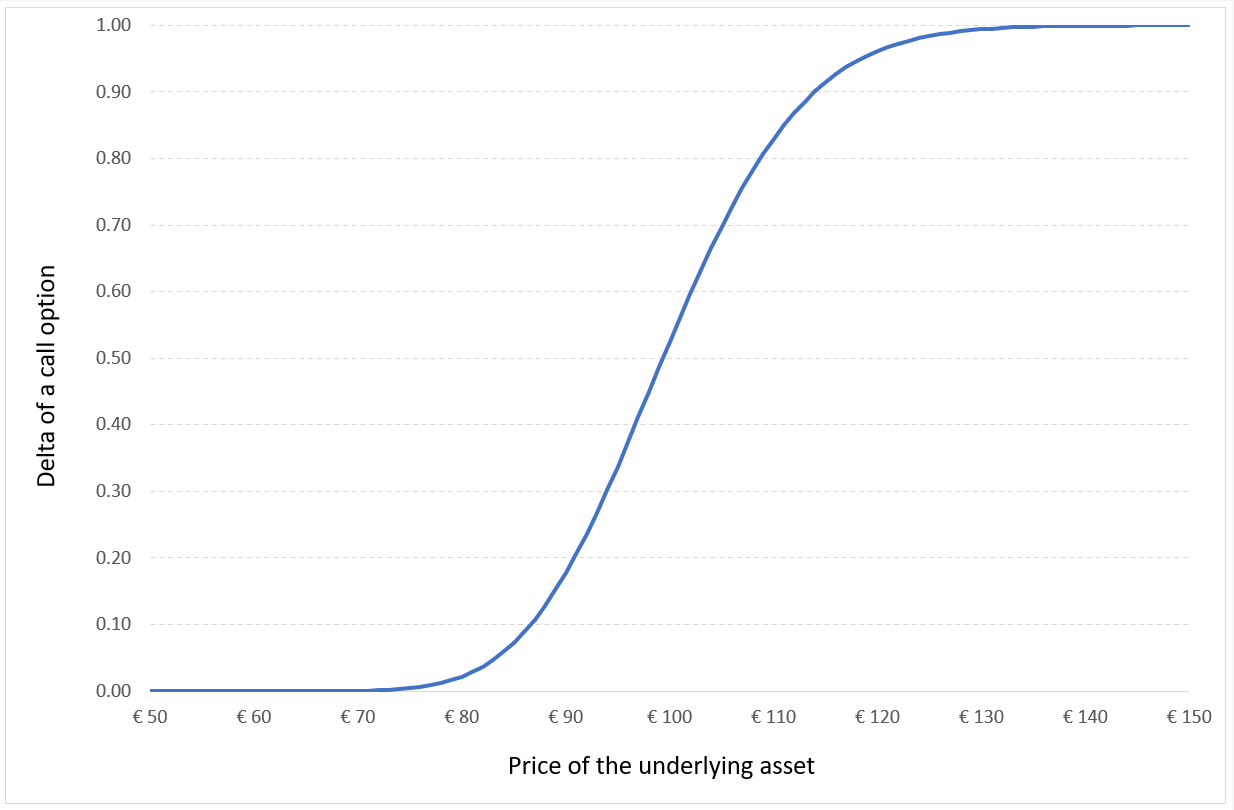

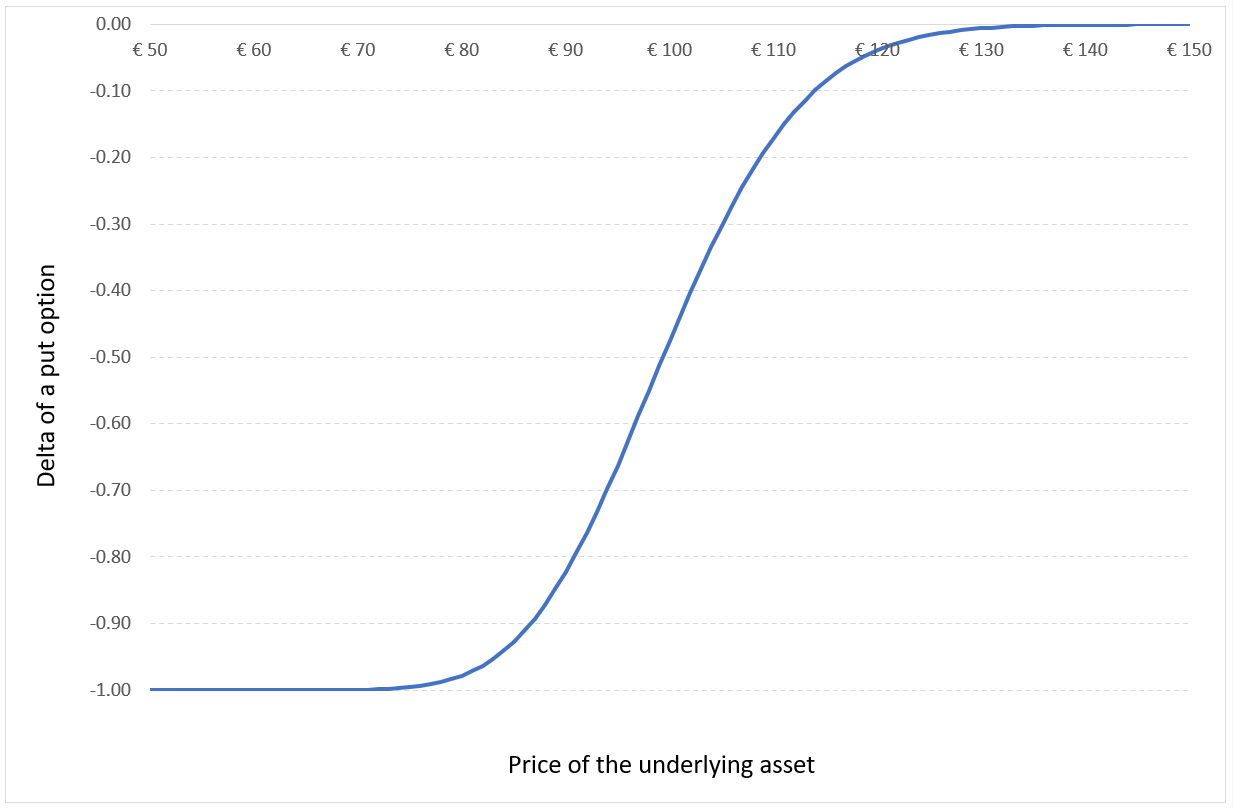

The figure below represent the theta of a call option as a function of the time to maturity:

Figure 1. Theta of a call option as a function of time to maturity.

Source: computation by the author (Model: Black-Scholes-Merton).

Intrinsic and time value of an option contract

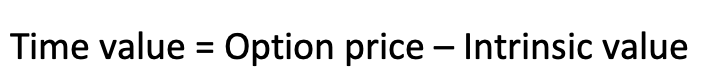

Essentially, the price of an option contract consists of two values namely, the intrinsic value and the time value (sometimes called extrinsic value). The intrinsic value in the price of an option contract is the real value or the fundamental value of an option based on the price of the underlying asset at a given point in time.

For example, a call option contract has a strike price of $10 and the underlying asset has a market price of $17. Theoretically, the buyer of a call option can execute the contract and buy the asset at $10 and sell it in the market for $17. He/she can make an immediate profit of $7 if they decide to exercise the option. Thus, the intrinsic value of the option contract is $7.

If the current call option price/premium is $9 in the market and the intrinsic value is $7, then the time value can be calculated as:

Thus, the time value is $9-$7 is equal to $2. The $2 is the time value of an option contract which is determined by the factors other than the price of the underlying asset. As the option approaches maturity, the time value of the option contract declines and tends to zero. The price of an option contract which is at the money or out the money, it consists entirely of the time value as there is no intrinsic value involved.

For example, a call option contract with a strike price of $20, the underlying asset price of $15, and option premium of $3, has a time value equal to the option premium, $3, since the option is out of money.

Calculating Theta for call and put options

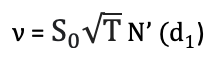

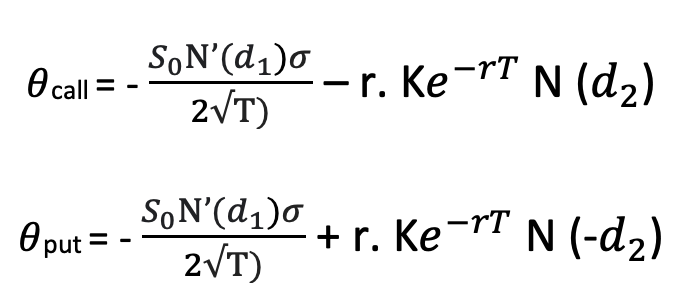

The theta for a non-dividend paying stock in a European call and put option is calculated using the following formula from the Black-Scholes Merton model:

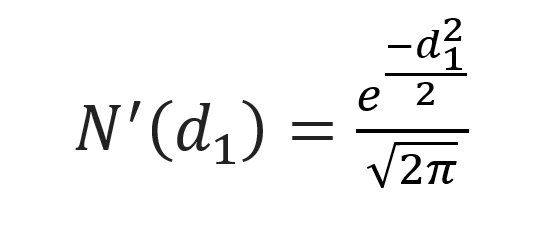

Where N’(d1) represents the first order derivative of the cumulative distribution function of the normal distribution given by:

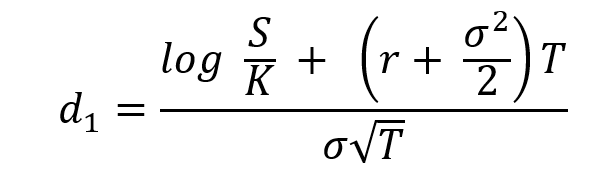

d1 is given by:

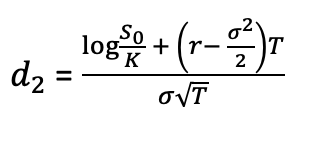

d2 is given by:

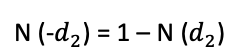

And N(-d2) is given by:

Where S is the price of the underlying asset (at the time of valuation of the option), σ the volatility in the price of the underlying asset, T time to option’s maturity, K the strike price of the option contract and r the risk-free rate of return.

Excel pricer to calculate the theta of an option

You can download below an Excel file for an option pricer (based on the Black-Scholes-Merton or BSM model) which allows you to calculate the theta of a European-style call option.

Example for calculating theta

Let us consider a call option contract with the following characteristics: the underlying asset is an Apple stock, the option strike price (K) is equal to $300 and the time to maturity (T) is of one month (i.e., 0.084 years).

At the time of valuation, the price of the Apple stock (S) is $300, the volatility (σ) of Apple stock is 30% and the risk-free rate (r) is 3% (market data).

The theta of a call option is approximately equal to -0.2636 per trading day.

Using the above example, we can say that after one trading day, the price of the option will decrease by $0.2636 (approximately) due to time decay.

Related Posts on the SimTrade blog

▶ Akshit GUPTA Options

▶ Akshit GUPTA History of Options markets

▶ Akshit GUPTA Option Trader – Job description

▶ Jayati WALIA Black-Scholes-Merton option pricing model

▶ Akshit GUPTA The Option Greeks – Delta

▶ Akshit GUPTA The Option Greeks – Gamma

▶ Akshit GUPTA The Option Greeks – Vega

Useful resources

Hull J.C. (2015) Options, Futures, and Other Derivatives, Ninth Edition, Chapter 19 – The Greek Letters, 424–431.

Wilmott P. (2007) Paul Wilmott Introduces Quantitative Finance, Second Edition, Chapter 8 – The Black Scholes Formula and The Greeks, 182-184.

About the author

Article written in August 2021 by Akshit GUPTA (ESSEC Business School, Master in Management, 2019-2022).