The return of inflation

In this article, Alexandre VERLET (ESSEC Business School, Master in Management, 2017-2021) explains how inflation could become an issue again for the first time in 40 years.

Inflation is not something we usually worry about. In fact, few understand what inflation is about beyond the fact that it is characterized by a rise in prices. But since inflation has been around for 40 years without causing any problem, it seems to be absolutely not dangerous and perfectly controlled by central banks. Problem is, the Covid-19 crisis and the economics policies launched by governments and central banks in response are unprecedented. Moreover, an excess of inflation can be a major problem for developed economies: the UK in the 1970’s was Europe’s sick man and had to revolutionize its economy the hard way in order to get out of its stagflation spiral.

So why are we talking about a 40 year old subject? Because for several weeks now, markets have been worried about a sustained return of inflation. Fantasy for some, harsh reality for others: the scenario of a sustainable return of inflation is far from unanimous among economists. None of them, however, disputes the appearance of signals favorable to an at least temporary rise in prices, even if the extent of the phenomenon is debated. Indeed, the latest figures from the United States speak for themselves: in April, prices there rose by 4.2% over one year. This is the first time since September 2008 that the markets have been particularly nervous in recent days. In the euro zone, inflation, although more moderate (+1.6% year-on-year), also seems to be accelerating as economies are recovering from the crisis.

What is inflation and what is causing it to return?

To put it simply, inflation is the sustained rise of general prices over a period of time. It is calculated using a basket of products in which their weight in the GDP is taken into account so the basket represents the economy as a whole. The causes of inflation can be derived from a simple phenomenon: the imbalance between supply and demand of good. In our case, all the ingredients were in place for a rise in prices. Initially, the end of the Covid-19 epidemic in China and the roll-out of the vaccination campaign, particularly in the United States, contributed to the sudden rebound in global demand. But the supply side was not able to keep up with the movement and meet all the needs, since supply chains and production processes are still disorganized. Adding to that, some countries remain closed, and global supply chains cannot be restarted overnight after more than a year of pause. As a result, bottlenecks have developed in some sectors and manufacturers are now facing shortages of raw materials. Companies must also adapt their production processes under the Covid-19 regulation, and all this has a cost.This automatically leads to higher production costs, which companies pass on in their prices.

Beyond the tensions on the goods and services market, other signals are worrying the markets across the Atlantic. Starting with Joe Biden’s three stimulus plans, which will involve almost 30% of US GDP. These massive plans, which are flourishing both in the United States and in Europe, are encouraged by the central banks’ accommodating policy and their unlimited power of money creation which, through asset purchases, allow governments to go into debt at lower cost. But by injecting so much money to stimulate demand, the Fed and the White House are taking the risk of putting the US economy in a state of overheating which could lead to a surge in prices in the US and, by contagion, in Europe. This is the principle of the quantitative theory of money developed by the economist Milton Friedman in 1970 when he stated that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon in the sense that it is and can be generated only by an increase in the quantity of money faster than the increase in output. The other phenomenon fueling fears of a sustained acceleration in prices is the tightness in the US labor market. Some sectors are facing a shortage of labor, including low-skilled workers, which could restart the “wage-price loop”. Several companies, including McDonald’s and Amazon, have already announced a significant increase in their minimum wage and attractive hiring bonuses to attract new candidates to the United States.

How would the return of the inflation impact us?

If it does not exceed a certain level, inflation is not necessarily harmful to the economy and can even be good for some. Keep in mind that the European Central Bank is aiming for an inflation rate close to but below 2% per year. The markets fear the return of inflation, but everyone is waiting for this inflation. Since 2008, the world entered a phase of low inflation but also of risk of deflation. While rising prices cause consumers to lose purchasing power in the short term, they often result in higher wages in the medium term. Not least because the French minimum wage is indexed to inflation, as are a number of social benefits. And an increase in the minimum wage most often results in an increase in the lowest wages, as explained by INSEE in a study on wages in France. In addition, employee representatives usually use inflation as a reason to obtain wage increases during annual negotiations in the company. If the employer accepts an increase at least equal to that of prices, then the purchasing power of employees remains stable. But one of the main winners from an acceleration of inflation is the state. When prices rise across the board, tax revenues increase. Another positive consequence is that inflation increases the capacity to repay public debt, since it increases nominal GDP and thus reduces the debt/GDP ratio. The same mechanism applies to all borrowers. At least if wages keep pace with inflation over time. Let us take the case of an employee earning 2000 euros per month. This person has taken out a fixed-rate loan with a monthly payment of 500 euros. Let us also assume an inflation rate of 2% for three consecutive years. Assuming that wages increase at the same rate, the employee will receive 2122 euros per month three years later but will still have to continue to repay 800 euros. His debt ratio would then fall from 32% to 30%. It would then be easier for him to repay his loan. The opposite is true for savers. When inflation is higher than the rate of return on savings, which is the case for the Livret A, the real return becomes negative. This means that the capital invested loses value. Finally, civil servants or pensioners can also be the big losers of a return of inflation if their income is not revalued in line with inflation, as has been the case in recent years. Provided that it is not excessive, inflation is not always a bad thing and is even often synonymous with growth. The question is therefore to know how much inflation will be and whether it will be sustainable.

In the current context, the prospect of uncontrolled inflation cannot be ruled out. The pre-existing equilibrium was not one of non-existent inflation, but one of well-anchored inflation expectations. The extremely accommodating fiscal and monetary policies are now threatening that balance.

If private agents start to doubt the willingness and ability of their central bank to defend price stability, then expectations may be derailed and a return to normal inflation would require huge sacrifices. To prevent expectations from deteriorating further, the central bank would be forced to absorb liquidity by a reverse quantitative easing, which would cause a rise in long-term rates and a contraction in economic activity. As a consequence, the ability of States to take on debt would become severely limited, which would threaten the sustainability of post-covid recovery plans.

Should we worry about the future because of inflation?

The inflation threat should be definitely be treated seriously by central banks. Nevertheless, the scenario of an uncontrolled inflation remains unlikely, especially in Europe where the stimulus package were far from the size of Biden’s plan. Firstly, the rise in prices in the United States is largely temporary. The shortage of raw materials and labor will eventually fade, so the resulting inflation should do the same. Secondly, the inflation figures observed in April should be put into perspective as they reflect a catch-up phenomenon. Indeed, demand had fallen at the same time last year due to the confinement, which had also pushed prices down. It should also be noted that the increase in prices in the US is highly sectorised: one third of the monthly inflation in April was linked to the evolution of second-hand car prices. And if we exclude volatile prices such as energy and food, US inflation reached 3% over one year. For their part, central banks such as the US Fed point out that a number of deflationary elements have not disappeared, starting with unemployment, which puts the risk of wage inflation into perspective. If inflation anticipations are still strong enough to offset those two trends, central banks will have to raise key rates to cool the economy in order to limit price increases. It would then be the end of the years of “free money”, and that is something that will impact all of us as potential borrowers. So keep an eye on economic indicators over the next few months!

Related posts on the SimTrade blog

▶ Verlet A. Inflation and the economic crisis of the 1970s and 1980s

About the author

Article written in August 2021 by Alexandre VERLET (ESSEC Business School, Master in Management, 2017-2021).

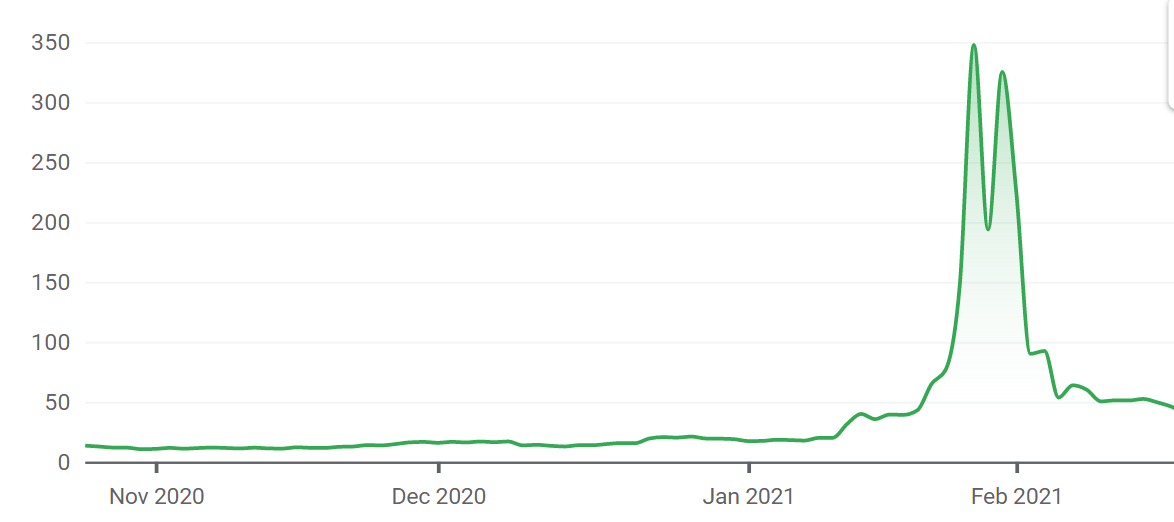

Source: GameStop

Source: GameStop