Eurozone Crisis 2011

This article written by Akshit Gupta (ESSEC Business School, Master in Management, 2019-2022) presents the real life case of the Eurozone Crisis 2011.

Introduction

The Eurozone Crisis, also called the European sovereign debt crisis, took place between 2010 and 2012 when several European countries faced an unmanageable increase in their sovereign debts, fall of their financial institutions and a sharp rise in the government bond yield spreads (difference between the yield of bonds issued by a country and the yield of bonds issued by Germany). The crisis was a result of excessive borrowing done by the Eurozone member states and a lowered refinancing or repayment capacity following the financial crisis of 2008.

Origin of the crisis

The Eurozone, also called the Euro area, was formed in 1999 with the primary aim to promote economic integration and have a stable, growth-oriented Europe by means of a unified primary currency across all member countries. Around 2010, Eurozone was comprised of 17 European countries all of which share a unified primary currency named Euro (€). The monetary policies of the Eurozone member states are governed by a central authority named the European Central Bank (ECB), whereas each country has the power to decide their fiscal and economic policies individually. As a result of a unified monetary framework, countries with weaker economy have access to more debt at a comparatively lower interest rates than before the creation of the Eurozone. Due to the excessive availability of debt, weaker countries increased their spending which resulted in high fiscal deficits. Since, the fiscal policies were controlled by countries individually, no centralized authority could keep a tab on it.

The beginning of the crisis came to light in 2009, when the new Greek government reported irregularities in the accounting system followed by the previous government. The new fiscal deficit showed a sovereign debt amounting to €300 billion which represented more than 110% of the country’s GDP at that time. The chances of default on the government’s debt started building up and the tension started to soar across the European continent.

The peak of the crisis

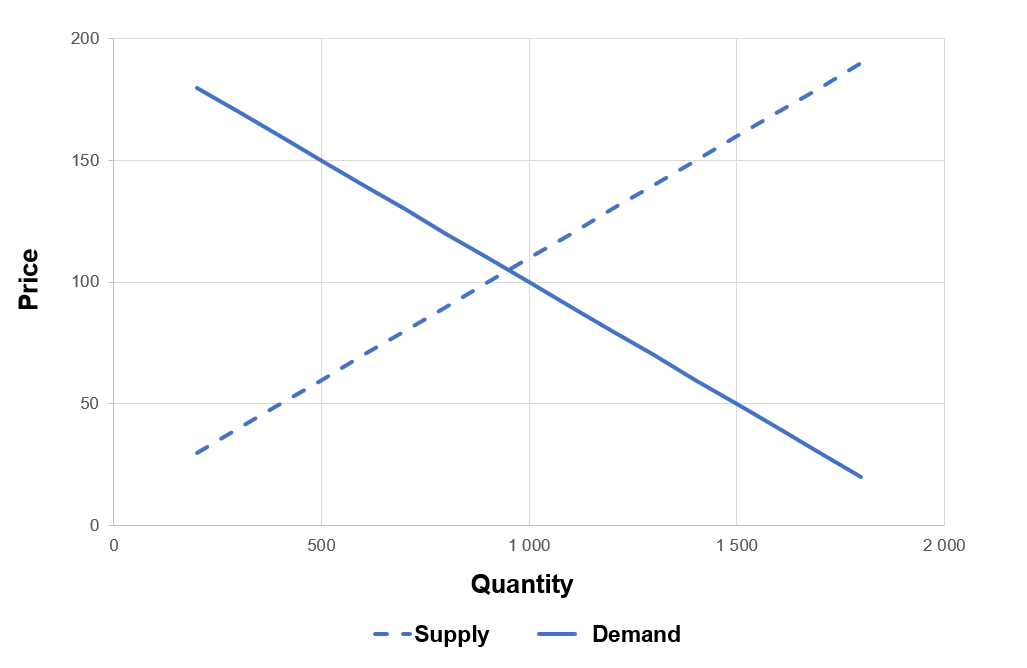

After the Greek government reported the higher levels of sovereign debt, rating agencies started downgrading the country’s debt ratings. The creditors started demanding higher yields on the government bonds, leading to higher borrowing costs for the government and a fall in the prices of these bonds (there is an inverse relationship between the price and yield of bonds). The fall in the prices of these securities sparked an outrage when many large European countries, financial institutions and central banks holding these securities started to lose money due to fall in their prices. By 2010, many other countries including Portugal, Italy, Ireland, and Spain reported similarly high level of sovereign debts.

Causes of the crisis

The Eurozone crisis was a result of many policy failures including high fiscal deficits, lack of unified body to monitor fiscal policies, trade imbalances, and also cultural differences. Some of the primary reasons that triggered the crisis are:

-

- The Eurozone crisis was triggered by the financial crisis of 2008 when access to capital at low interest rates became tough and the countries with high sovereign debt were unable to refinance or repay their debts without the intervention or help of other countries. During the recession that followed the financial crisis of 2008, tax revenues decreased whereas the public spending on unemployment benefits and infrastructure development increased. This resulted in further worsening the fiscal deficit for the weaker economies.

- Another cause for the crisis can be attributed to an easy access to cheap capital to the weaker countries during early 2000’s and a lack of centralized fiscal policy framework to put a check on the individual government borrowing and spending.

- The trade imbalance resulting from the flow of capital from developed countries like France and Germany to southern nations like Greece, Spain, Italy etc. led to an increase in the wages in these countries which was not matched by the increase in productivity. The increased wages led to an increase in prices of finished goods, thus making these country’s exports less competitive. The increase inflow of capital led to a trade deficit in these countries further aggravating the crisis.

Solutions

All the seventeen member states of the Eurozone voted to create a European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF), which was a temporary measure to provide financial assistance to the countries impacted by the sovereign debt crisis. With the intervention of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the European Central Bank and the EFSF, a bailout package was provided to the debt-ridden countries amounting to €1 trillion. Several conditions were applied on countries which received bailout funds from the EFSF. The countries were bound to apply severe EU-mandated austerity measures which were formed to reduce government deficits and sovereign debts to acceptable levels. But the measures also faced criticism from the impacted countries as it could have halted the economic recovery for the impacted countries by cutting their spending capacities.

The creation of the EFSF provided remedial measures to the impacted countries by means of financial assistance subject to certain reforms and conditions that the fund – receiving country must undertake. The EFSF functioned by issuing EFSF bonds and other marketable securities to lenders. The bonds and securities were secured and backed by the Eurozone member countries up to the proportion of their share of capital in the ECB.

After effects

In 2012, a European Stability Mechanism (ESM) was instated to replace the EFSF as a permanent financial stability and crisis resolution measure for the Eurozone countries. The ESM is fully backed by the members of the Eurozone. This backing provides a relief to the lenders and assures them of their capital protection. The crisis saw the creation of the Eurobonds, which are used as a new way of financing the bailout funds. The ESM is funded by issuance of Eurobonds worth €700 billion which are backed by the Eurozone countries.

Lessons learnt from the crisis

The Eurozone crisis has affected the world economy at large, posing a threat to the global markets. Although, the decisions taken by the Eurozone countries helped in containing the damage, some policy changes are required to prevent such events to happen in the future. Political consensus among Eurozone member countries is required to ensure efficient decision making. The coordination and monitoring of the fiscal policies along with the monetary policies of the Eurozone countries is also essential to ensure a balanced economy growth. The policy makers should implement centralized fiscal policies to ensure the long-term viability and stability of the European economies.

Relevance to the SimTrade certificate

The concepts about pricing of securities in the secondary market and incorporation of information in market prices can be learnt in the SimTrade Certificate:

About theory

-

-

- By taking the Trade orders course, you will know more about the different type of orders that you can use to buy and sell assets in financial markets.

- By taking the Market information course, you will understand how information is incorporated into market prices and the associated concept of market efficiency.

-

About practice

-

-

- By launching the Sending an Order simulation, you will practice how financial markets really work and how to act in the market by sending orders.

- By launching the Efficient market simulation, you will practice how information is incorporated into market prices through the trading of market participants and grasp the concept of market efficiency.

-

Useful resources

Solving the Financial and Sovereign Debt Crisis in Europe – by Adrian Blundell-Wignall

Investopedia Article – European Financial Stability Facility

Article written by Akshit Gupta (ESSEC Business School, Master in Management, 2019-2022).