Factor Investing

In this article, Youssef LOURAOUI (ESSEC Business School, Global Bachelor of Business Administration, 2017-2021) presents factor investing, which is an investment approach that focuses on distinct performance drivers across asset classes.

This article is structured as follows: we begin with the early works of factor investing (market factor). We then delve more in detail on the different factors available and their characteristics. We finish with an empirical analysis that aims to capture the performance of factor investing across time.

Early works

In the world of investing, a factor is a persistent driver that helps explain assets’ long-term risk and return properties across asset classes. It is important to understand how factors work to better capture their potential for excess return and reduced risk across asset classes.

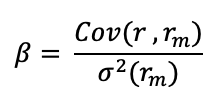

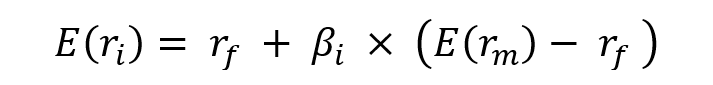

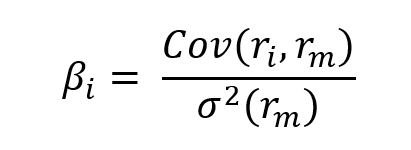

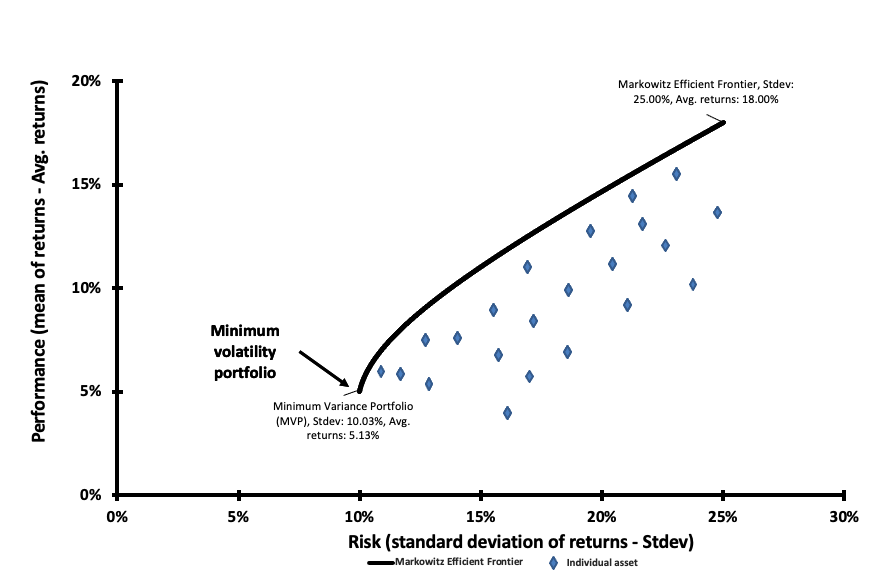

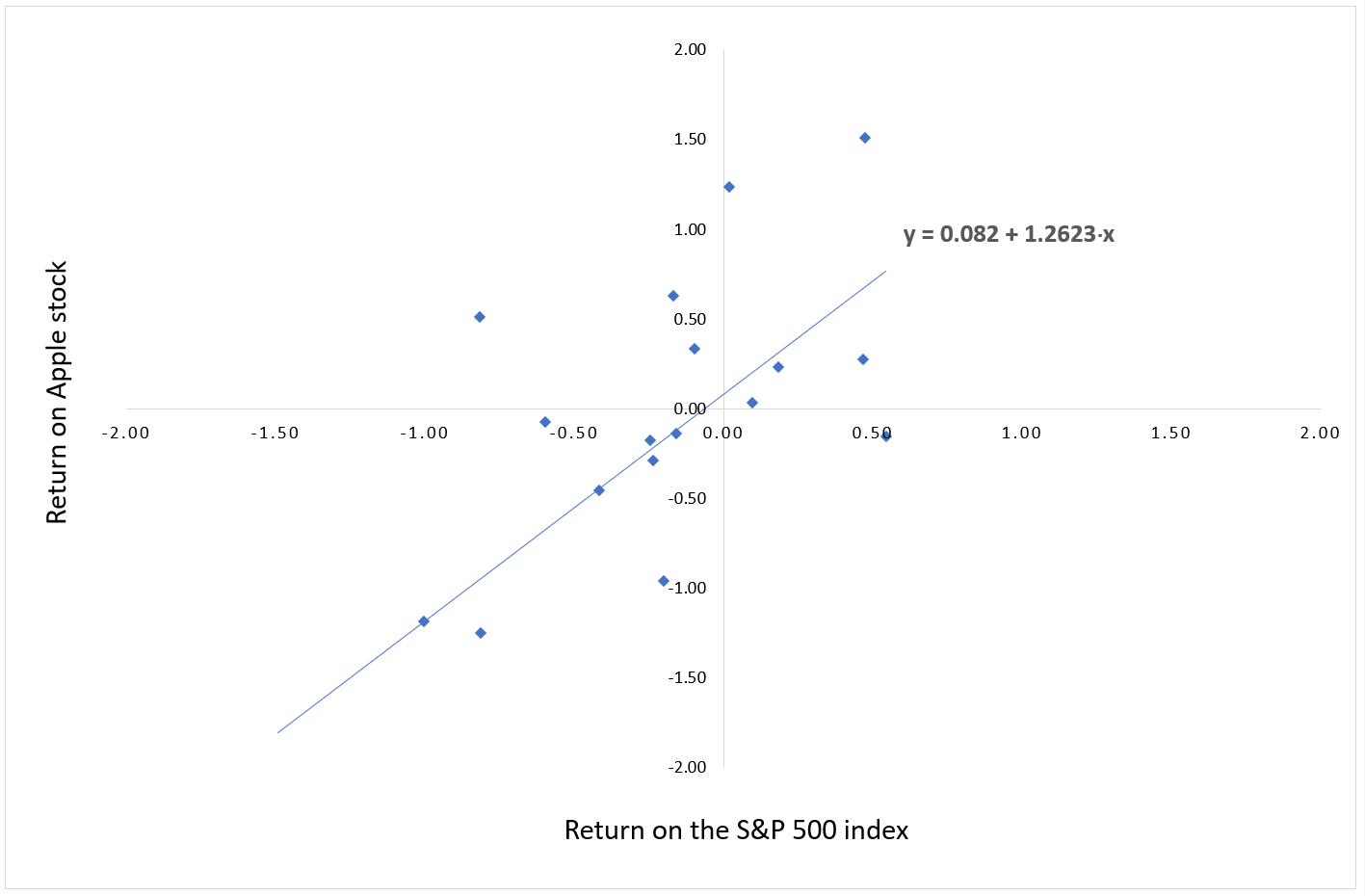

As a result of Harry Markowitz’s prior studies, William Sharpe, John Lintner, and Jan Mossin independently developed the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). The CAPM was a significant evolutionary step forward in capital market equilibrium theory because it allowed investors to value assets correctly in terms of systematic risk that impact all assets (Mangram, 2013). In the CAPM, the factor is the market factor representing the global uncertainty of the market.

In the late 1970s, the portfolio management industry aimed to capture the market portfolio return, but as financial research advanced and certain significant contributions were made, this gave rise to other factor characteristics to capture some additional performance.

Factor investing

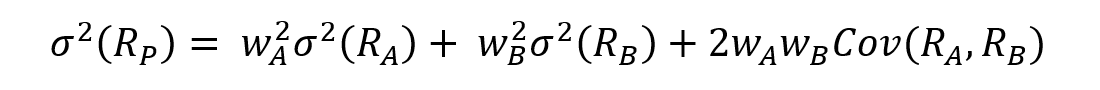

As defined by Blackrock (2021), “Factor investing” is an investment strategy that focuses on unique determinants of performance across asset classes. Factor investing may improve portfolio performance and decrease volatility by increasing portfolio diversification. Asset returns are driven by two main types of factors: macroeconomic factors and style factors. Macroeconomic factors capture broad risks across asset classes while style factors explain returns and risk within asset classes.

Considering macroeconomic factors, returns can be influenced by the following macroeconomic variables (BlackRock research, 2021):

- Economic growth: exposure to business and market cycles

- Real interest rates: sensitivity to interest rate movements

- Inflation: exposure to change in price

- Credit: default risk from lending to companies

- Emerging markets: political and sovereign risk

- Liquidity: holding liquid assets.

Considering style factors, returns can be influenced by the following style variables (BlackRock research, 2021):

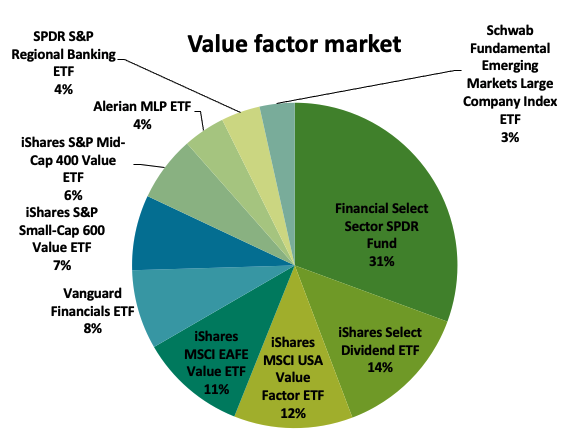

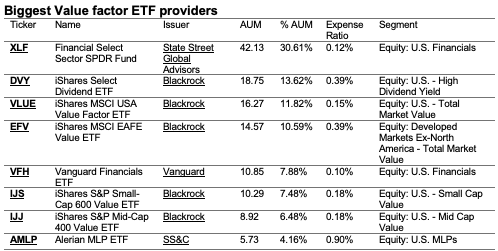

- Value: stocks discounted to relative value

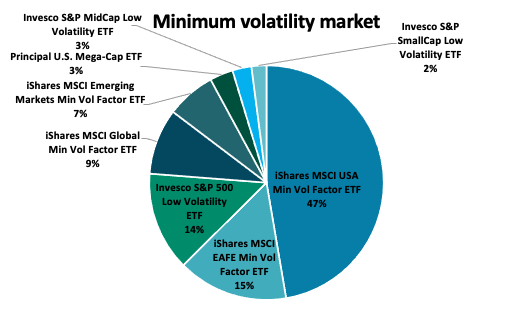

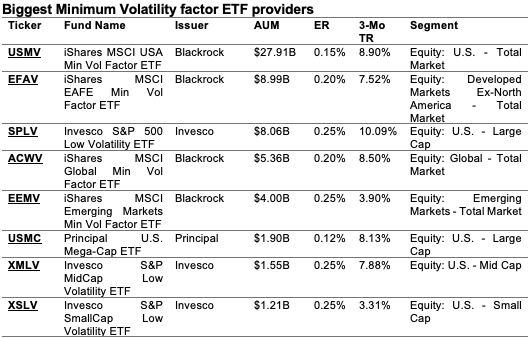

- Minimum volatility: stable, lower risk stocks

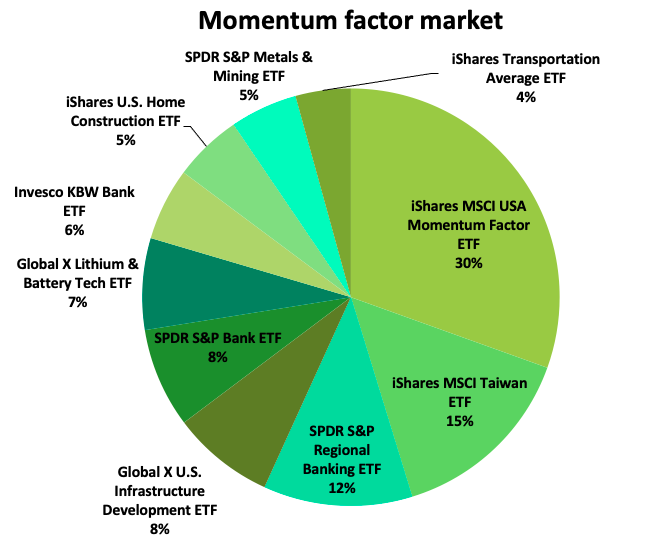

- Momentum: stocks with upward price trends

- Quality: financially healthy companies

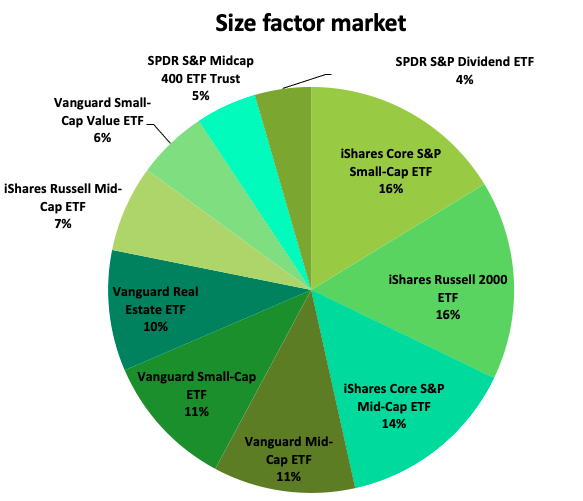

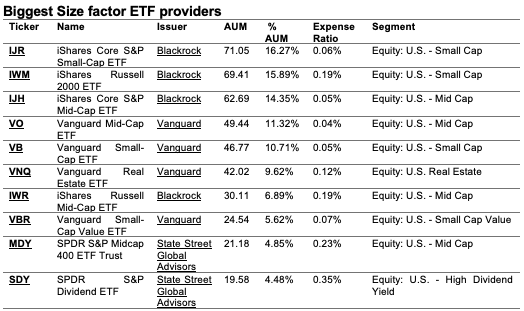

- Size: smaller, high growth companies

- Growth: companies that have a rate of growth above the market growth

- Yield: companies that have undervalued and stable dividends

Characteristics of a factor

As defined in the work of Ang (2013) a factor must comply with the following characteristics:

- A factor must be backed up by scholarly research: factors should have an academic basis. The research should illustrate either compelling logical reasoning or compelling behavioral biases, or both, in order to adequately justify the risk premium (Ang, 2013). Value, momentum, and minimum volatility among other strategies qualify as adequate risk factors under this criterion. New research may find new factors, qualify prior agreement on recognized factors, or even reject factors previously identified, all of which may be used to shape investment strategy.

- A factor must have maintained a substantial risk premium in the past and is anticipated to do so in the future: not only should investors understand why the risk premium existed in the past, but they should also have some reason to believe that it will continue to exist in the future (at least in the short run). By definition, factors are systematic–they emerge from risk or behavioral patterns that will likely continue (again, in the short run), even if everyone is aware of the factors and many investors pursue the same factor strategies (no crowding effect).

- A factor must be capable of being implemented in liquid, tradable instruments: factor strategies should be very inexpensive, which is best done via the use of liquid securities.

Academic literature on factor investing

Numerous academic studies and years of investing experience have revealed some types of stock, debt, and derivative assets with larger payoffs than the broad market index. Over extended periods of time, equities with low price-to-book ratios (value stocks) outperform those with high price-to-book ratios (growth stocks), creating a value-growth premium (Ang, 2013). Over time, equities with a history of high or positive returns (winners) outperform those with a history of low or negative returns (losers). This is at the heart of momentum strategies, which seeks to get exposure to stocks that have a winning tendency in the upside and downside assuming that they will continue to do well in the short term (Ang, 2013).

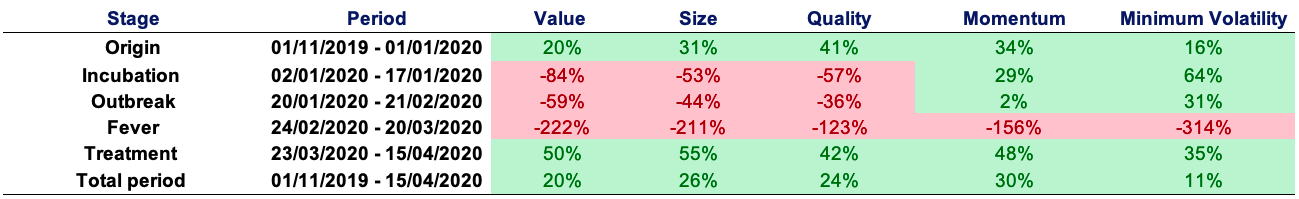

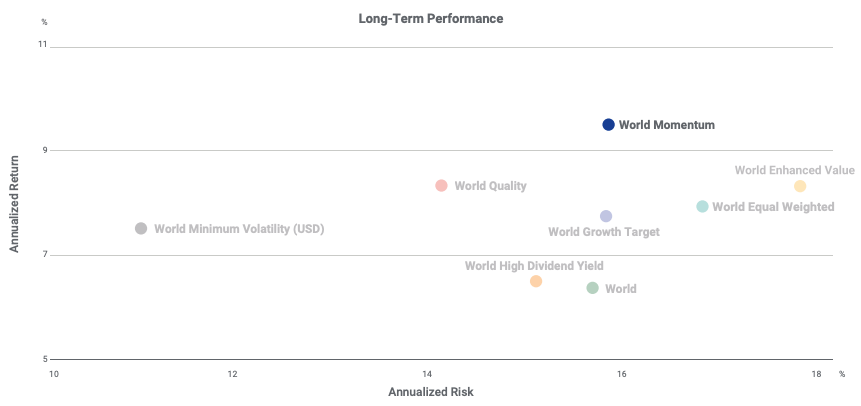

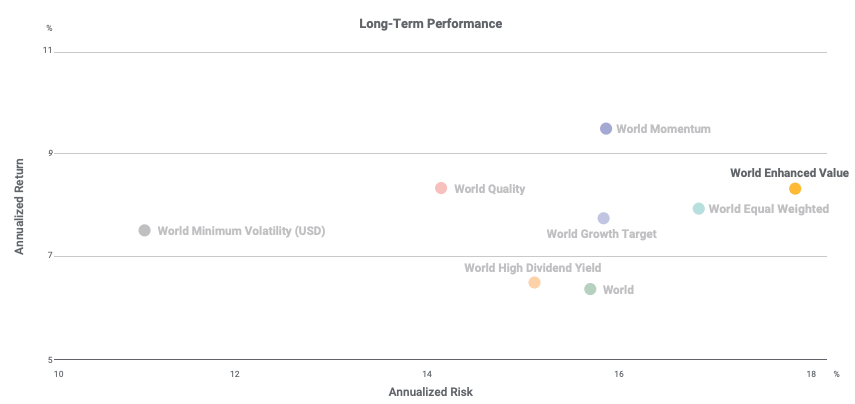

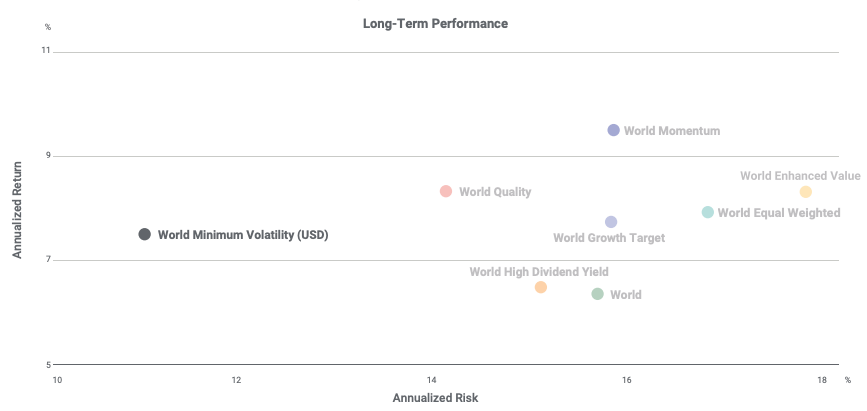

Investors seeking downside protection in a turbulent market environment may increase exposure to low volatility strategies, while those comfortable with more risk may choose for higher-return strategies such as momentum. The financial literature has explored deeper to show that some factors have had a long-term impact on returns. These factors contributed to returns for three reasons: an investor’s desire to take on risk, structural obstacles, and the reality that not all investors are not always entirely rational (BlackRock research, 2021). Particular factors yield higher returns as a result of increased risk but may underperform in certain market conditions. Enhanced methods use factors in more sophisticated ways, such as trading across various asset classes and sometimes investing in both long and short positions. These improved factor strategies are used by investors seeking absolute returns or as a supplement to hedge funds and classic active strategies (BlackRock research, 2021).

Securities that are less liquid trade at a discount to their more liquid counterparts and earn a higher average excess return on average. As a result, a premium is charged for illiquidity (Ang, 2013). Bonds with a greater risk of default often have higher average returns, owing to the credit risk premium. Additionally, because investors are ready to pay for protection against periods of extreme volatility, when returns tend to fall, sellers of volatility protection in option markets receive a high rate of return on average (Ang, 2013). As a result, investors can collect the premiums as follows (Ang, 2013):

- The value-growth premium is equal to the difference between value and growth stocks.

- The momentum premium is equal to the difference between winning and losing stocks.

- The illiquidity premium is equal to the difference between the value of illiquid assets and the value of liquid assets.

- The credit risk premium is the difference between the return on risky and safe debt.

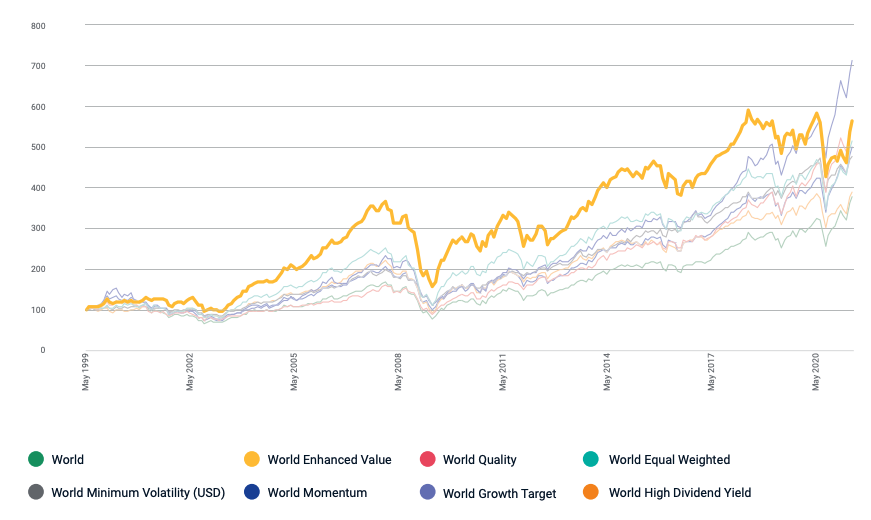

These are dynamic factors, since they reflect time-varying holdings in securities that fluctuate in value over time. While dynamic factors frequently outperform the market over extended periods of time, they can significantly underperform at select occasions — such as the 2008-2009 financial crisis. While dynamic factors frequently outperform the market over extended periods of time, they can outperform the market significantly at select moments — such as the 2008-2009 financial crisis. In the long term, factor risk premiums exist to compensate investors for experiencing losses during difficult times (Ang, 2013). In the end, the factors are not ideal for everyone due to the inherent risk associated with factor techniques.

Empirical analysis

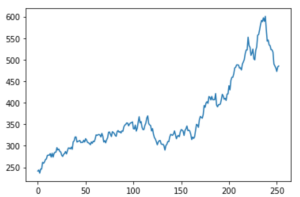

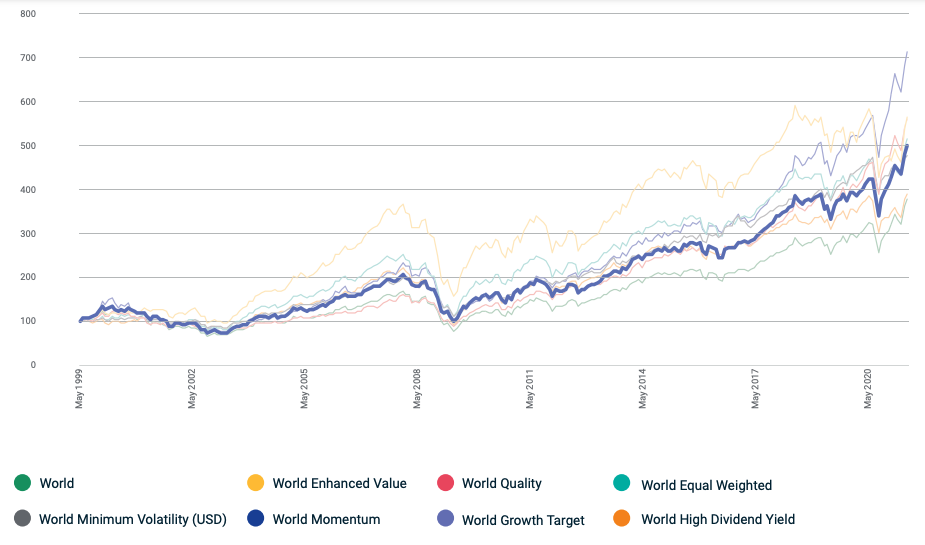

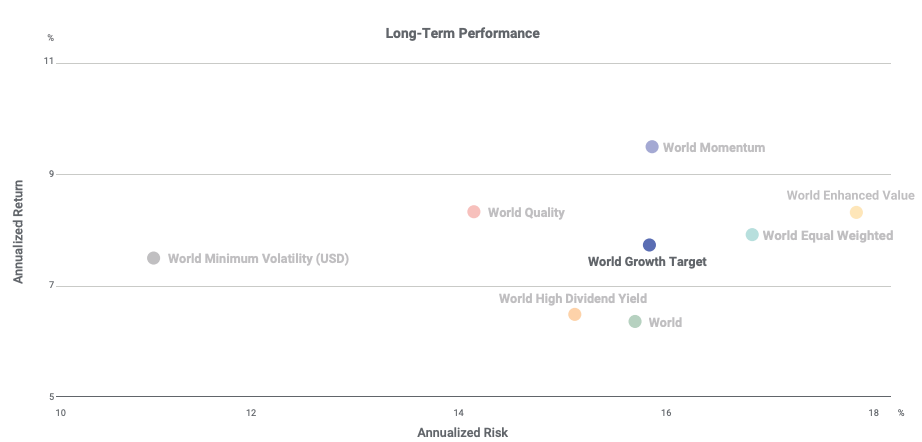

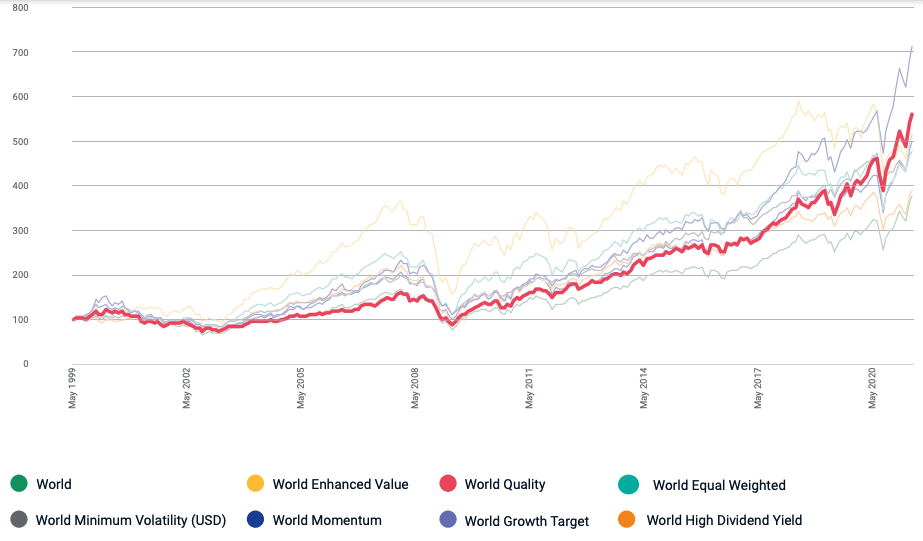

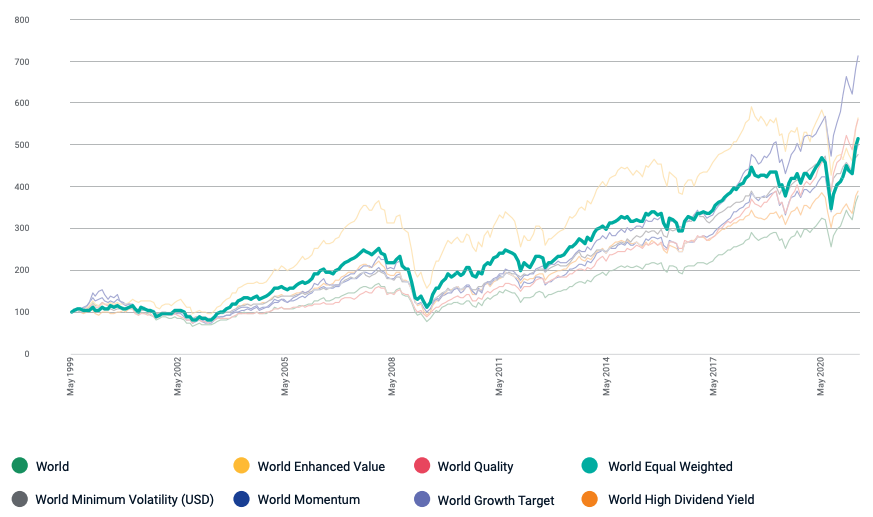

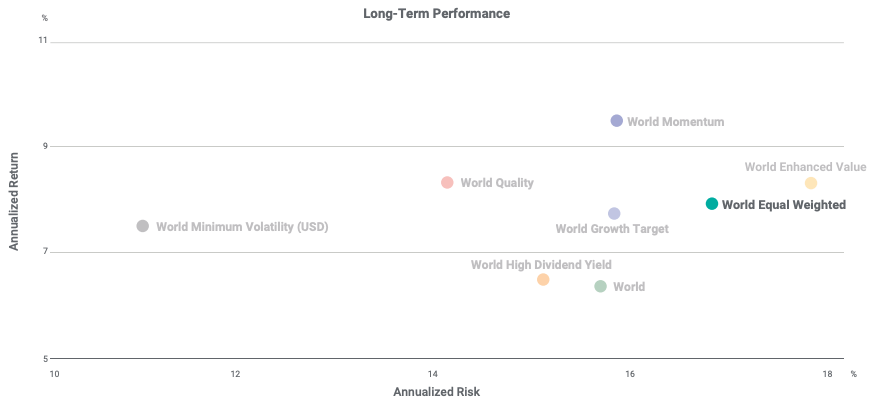

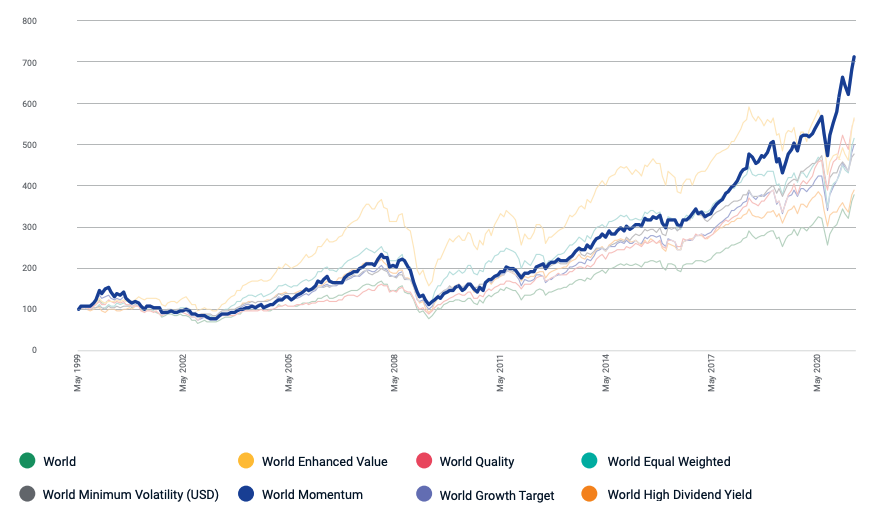

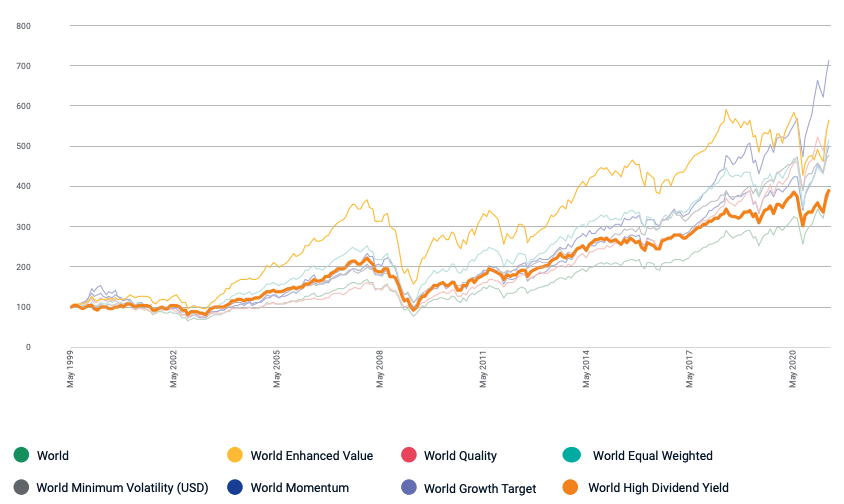

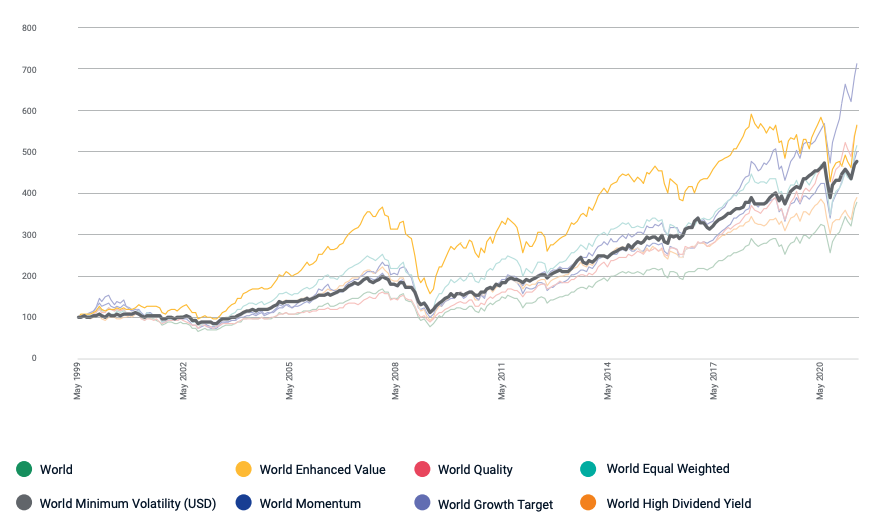

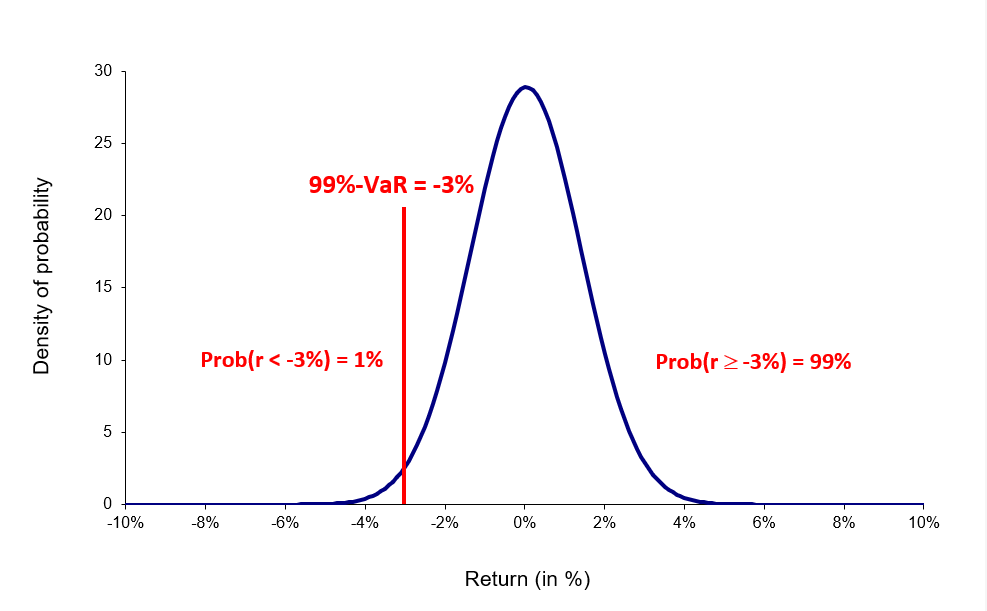

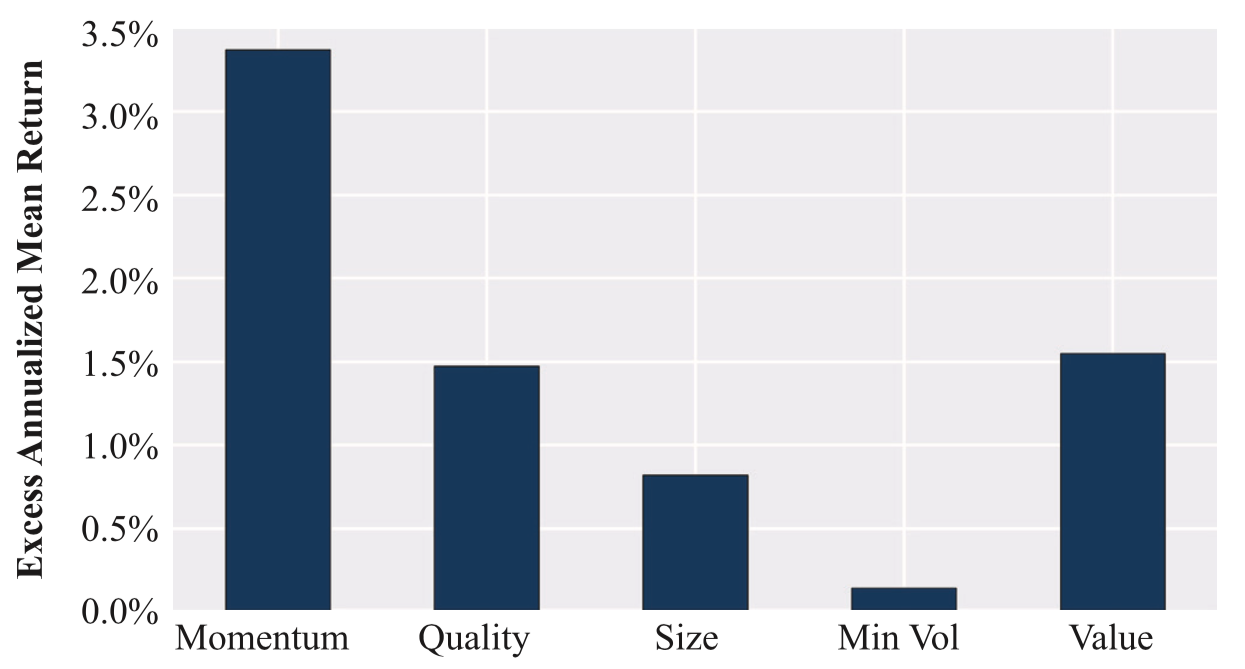

Hodges et al. (2017) published a study in the Journal of Portfolio Management that looks at the performance of factor funds over a 30-year period and examines the vectors of returns). Figure 1 illustrates the average excess returns (above the MSCI USA Index) of each factor from June 30, 1988 to September 30, 2016. Value, quality, momentum, and size all have positive average returns; momentum and value have the largest annual excess returns of 3.4 percent and 1.5 percent, respectively. Minimum volatility has generated an average return comparable to the market (but with less risk), similar with Ang’s findings (Hodges et al., 2017).

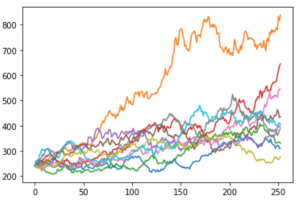

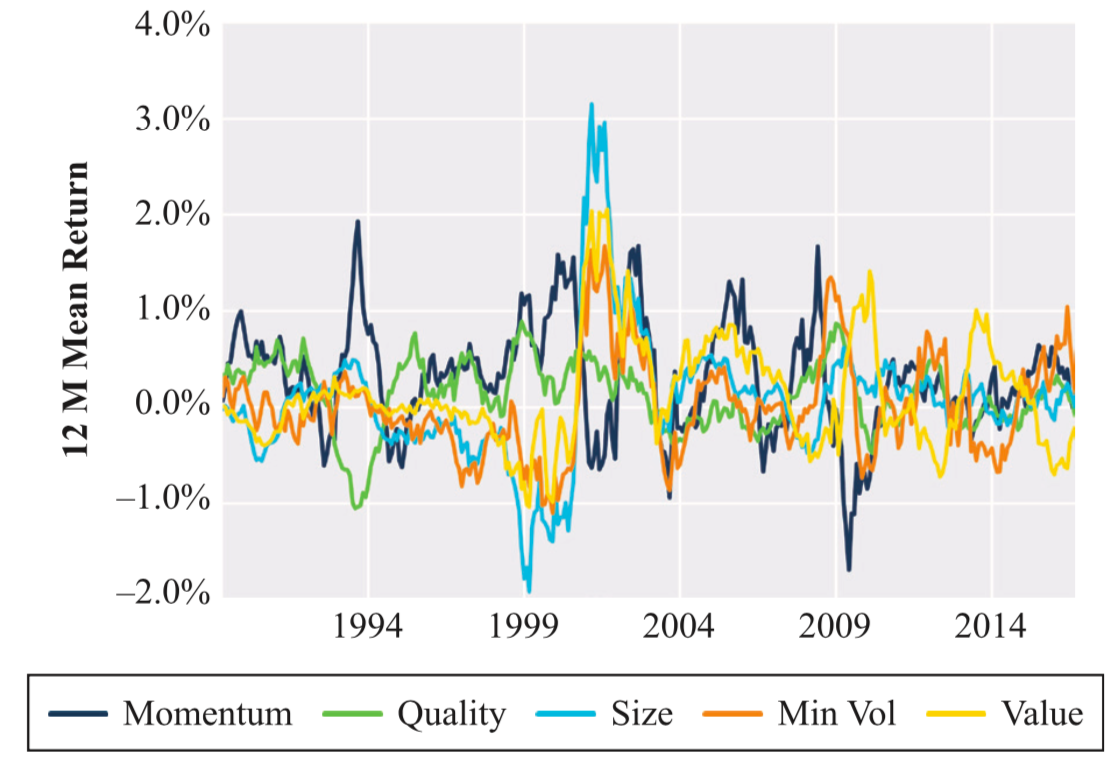

Figure 2 plots 12-month moving averages of excess factor returns and demonstrates that, while longrun excess premiums are positive, there is significant temporal variation throughout the sample. For instance, size changes from a negative 12-month mean return of -2.0 percent in 1999 to a positive 12-month mean return of 3.0 percent in the early 2000s.

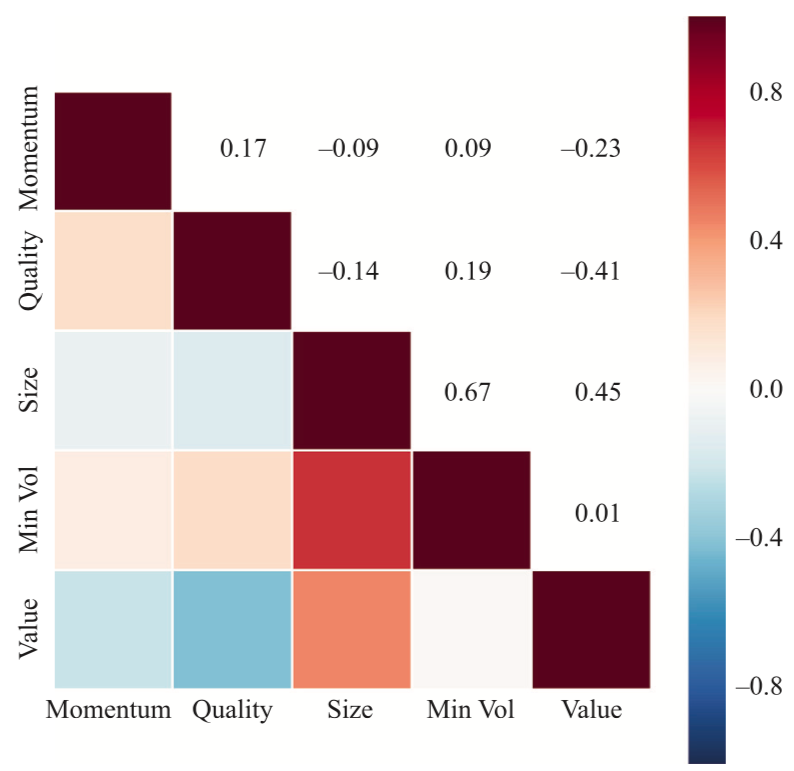

Figure 3 demonstrates that the excess factor returns are not substantially correlated: the lowest correlation is -0.42, while the largest is 0.67, between minimal volatility and size. Notably, momentum and value are negatively connected with a correlation coefficient of -0.22, which is consistent with their well-known negative association (Hodges, et al., 2017).

Why should I be interested in this post?

Numerous equity investors seeking greater returns at a cheaper cost have shifted their focus to factor investing. Active managers in the traditional sense typically make investing decisions based on their research of particular companies and their stocks. By contrast, factor strategies identify the qualities, or factors, that are most likely to beat the market and then invest in stocks that exhibit those characteristics. For instance, the value factor is based on the strategy of investing in companies that are undervalued in comparison to the market, whereas the momentum factor is based in the strategy of investing in equities that have recently seen a price acceleration.

Related posts on the SimTrade blog

▶ Youssef LOURAOUI Size Factor

▶ Youssef LOURAOUI Value Factor

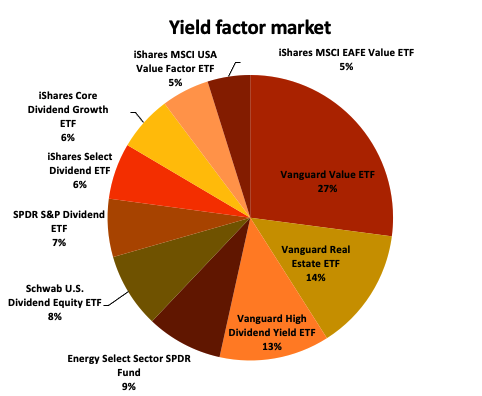

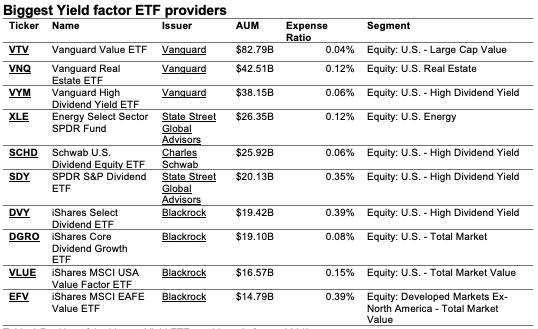

▶ Youssef LOURAOUI Yield Factor

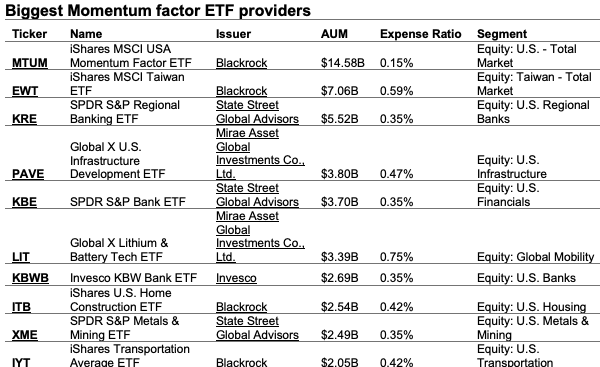

▶ Youssef LOURAOUI Momentum Factor

▶ Youssef LOURAOUI Quality Factor

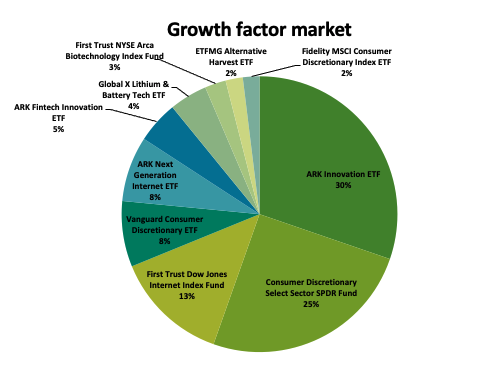

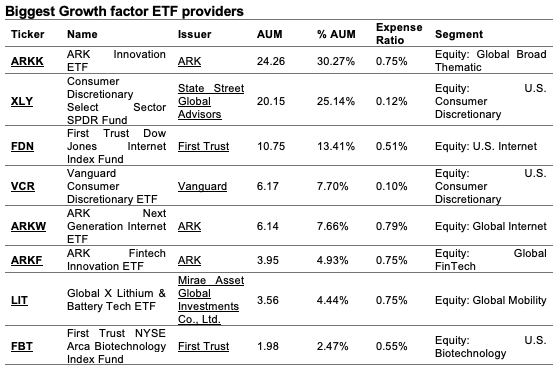

▶ Youssef LOURAOUI Growth Factor

▶ Youssef LOURAOUI Minimum Volatility Factor

Useful resources

Academic research

Ang, A., 2013. Factor Investing. Working paper.

Hodges, P., Hogan, K., Peterson, J. R., Ang, A., 2017. Factor Timing with Cross- Sectional and Time-Series Predictors. The Journal of Portfolio Management 44(1): 30-43.

Business Analysis

BlackRock research, 2021. What is Factor Investing?

About the author

The article was written in September 2021 by Youssef LOURAOUI (ESSEC Business School, Global Bachelor of Business Administration, 2017-2021).