Extreme Value Theory: the Block-Maxima approach and the Peak-Over-Threshold approach

In this article, Shengyu ZHENG (ESSEC Business School, Grande Ecole Program – Master in Management, 2020-2023) presents the extreme value theory (EVT) and two commonly used modelling approaches: block-maxima (BM) and peak-over-threshold (PoT).

Introduction

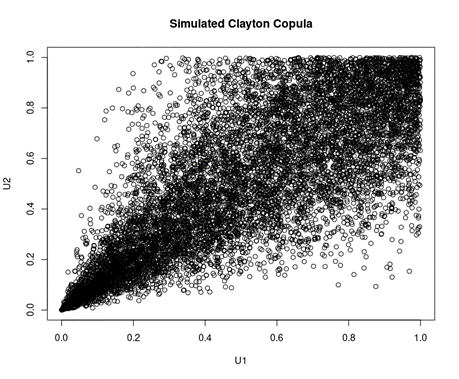

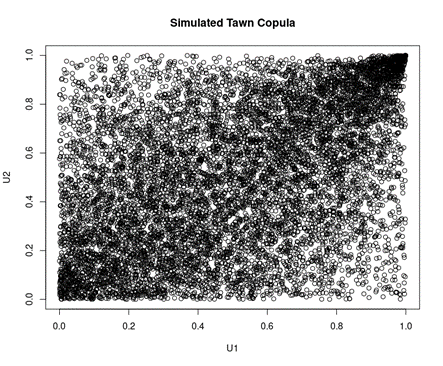

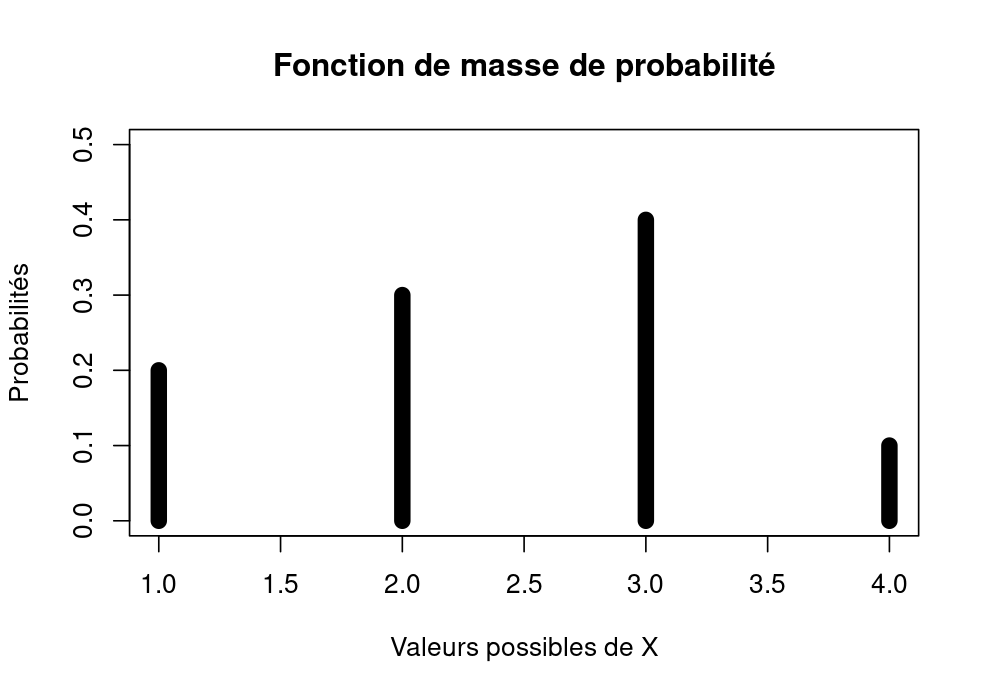

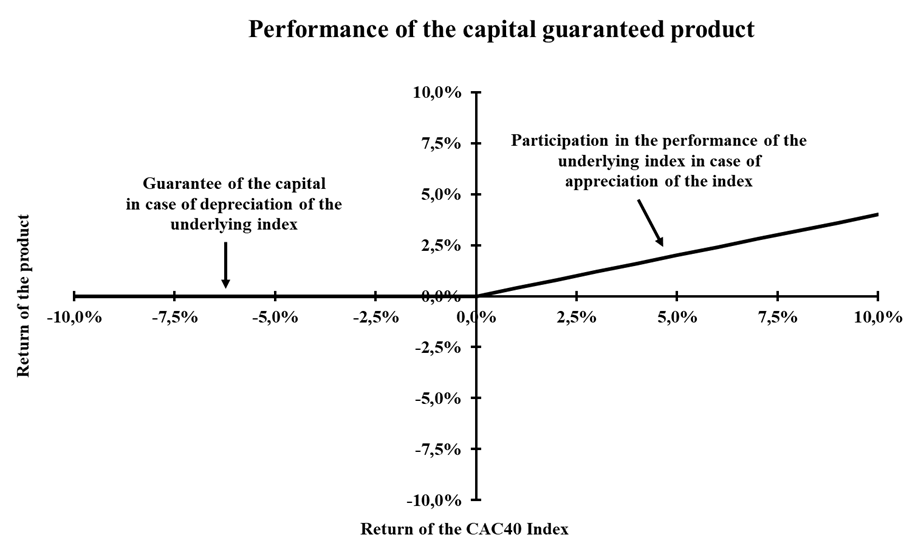

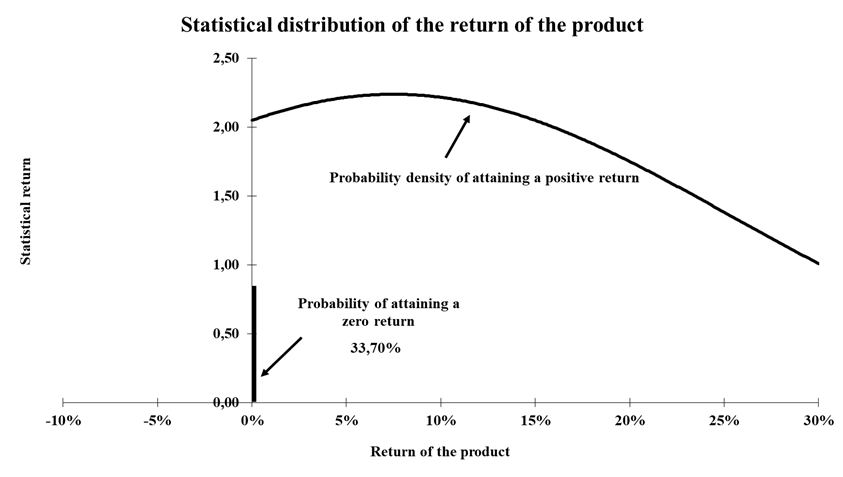

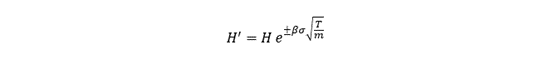

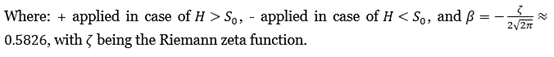

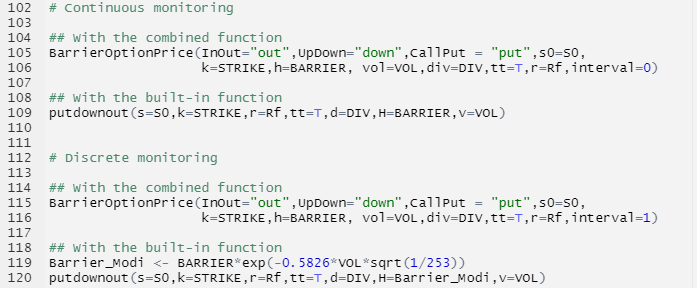

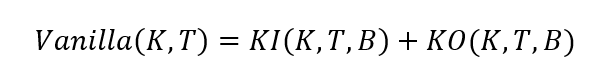

There are generally two approaches to identify and model the extrema of a random process: the block-maxima approach where the extrema follow a generalized extreme value distribution (BM-GEV), and the peak-over-threshold approach that fits the extrema in a generalized Pareto distribution (POT-GPD):

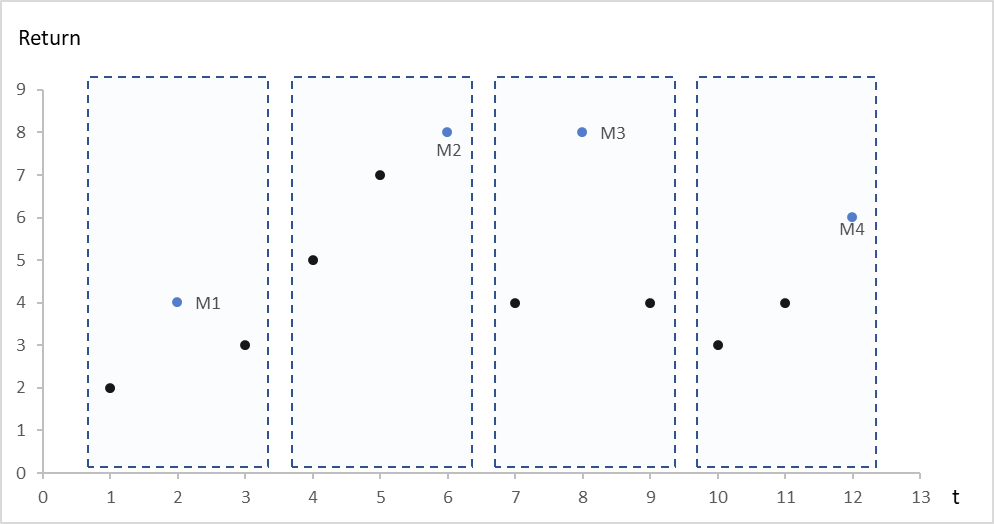

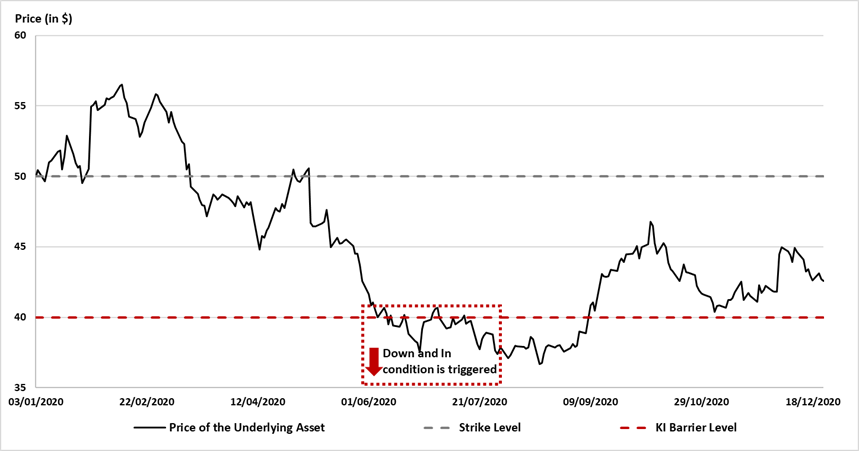

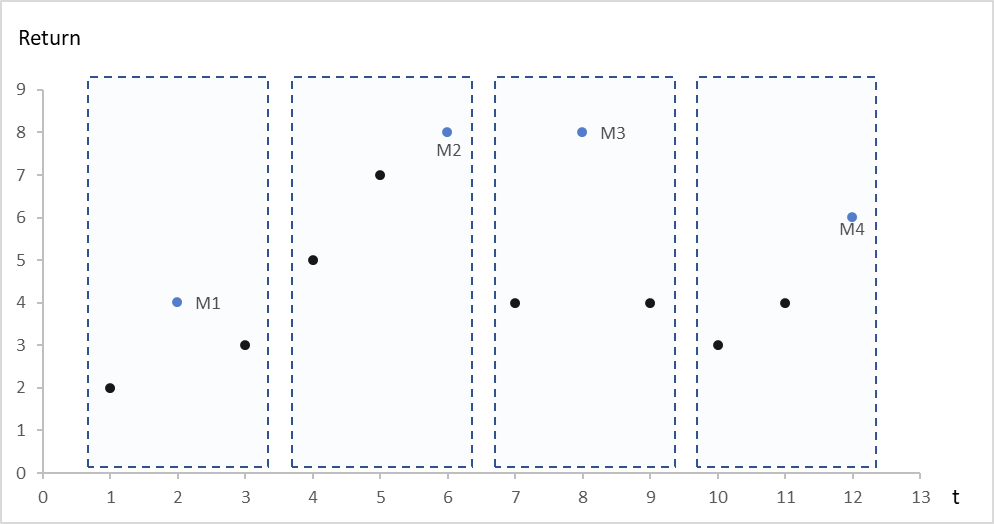

- BM-GEV: The BM approach divides the observation period into nonoverlapping, continuous and equal intervals and collects the maximum entries of each interval. (Gumbel, 1958) Maxima from these blocks (intervals) can be fitted into a generalized extreme value (GEV) distribution.

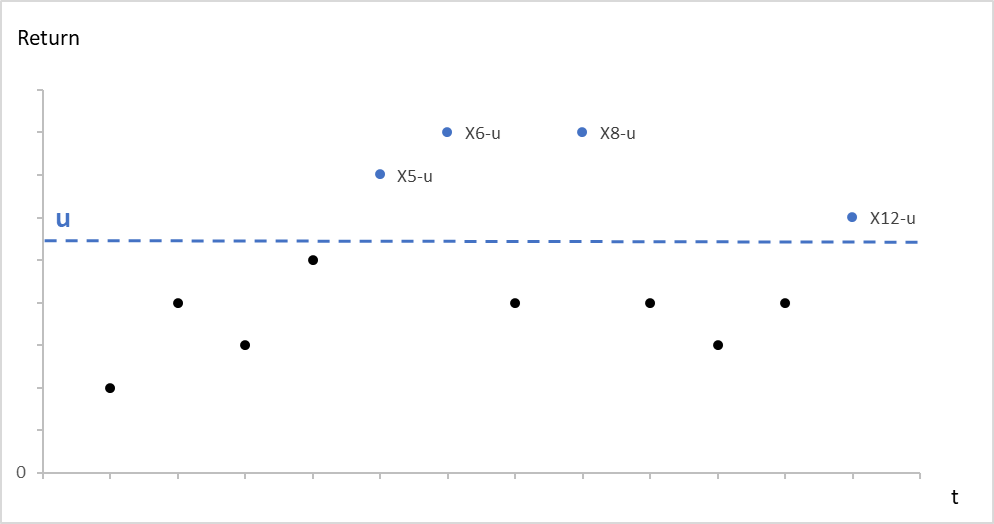

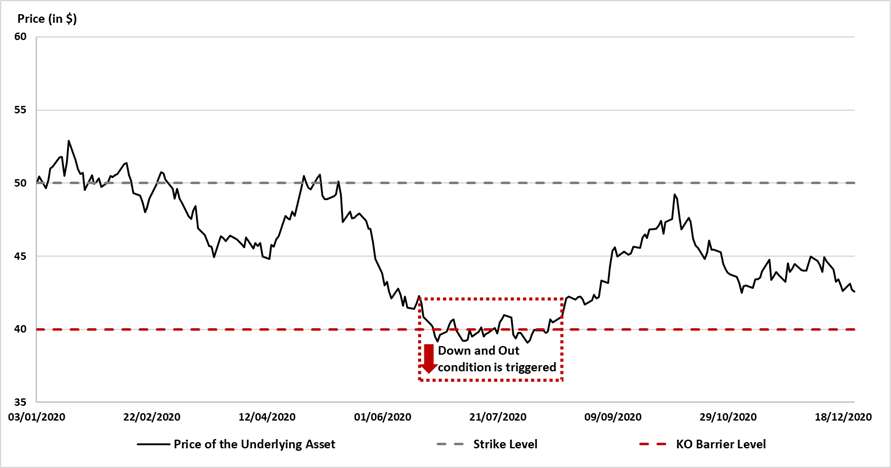

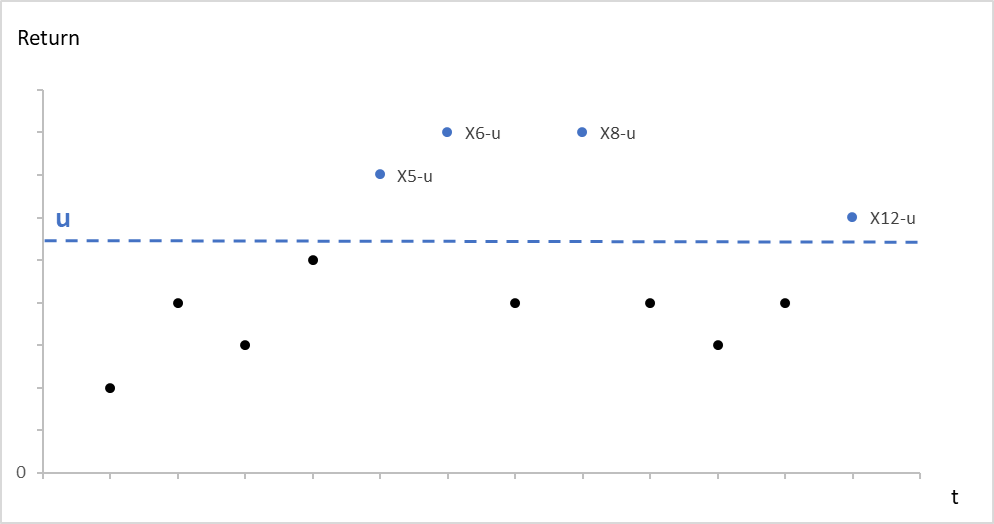

- POT-GPD: The POT approach selects the observations that exceed a certain high threshold. A generalized Pareto distribution (GPD) is usually used to approximate the observations selected with the POT approach. (Pickands III, 1975)

Figure 1. Illustration of the Block-Maxima approach

Source: computation by the author.

Figure 2. Illustration of the Peak-Over-Threshold approach

Source: computation by the author.

BM-GEV

Block-Maxima

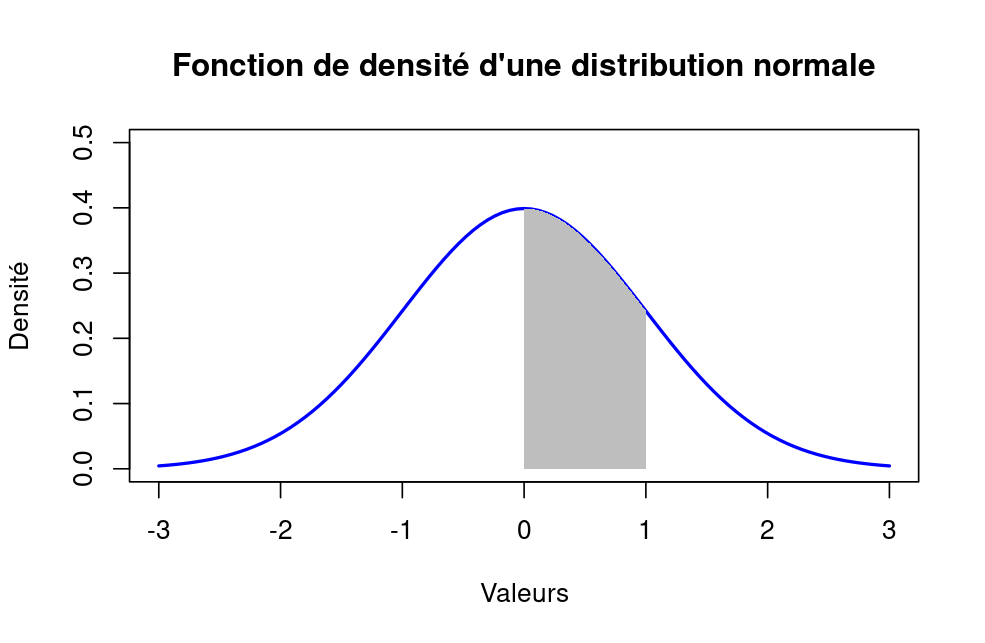

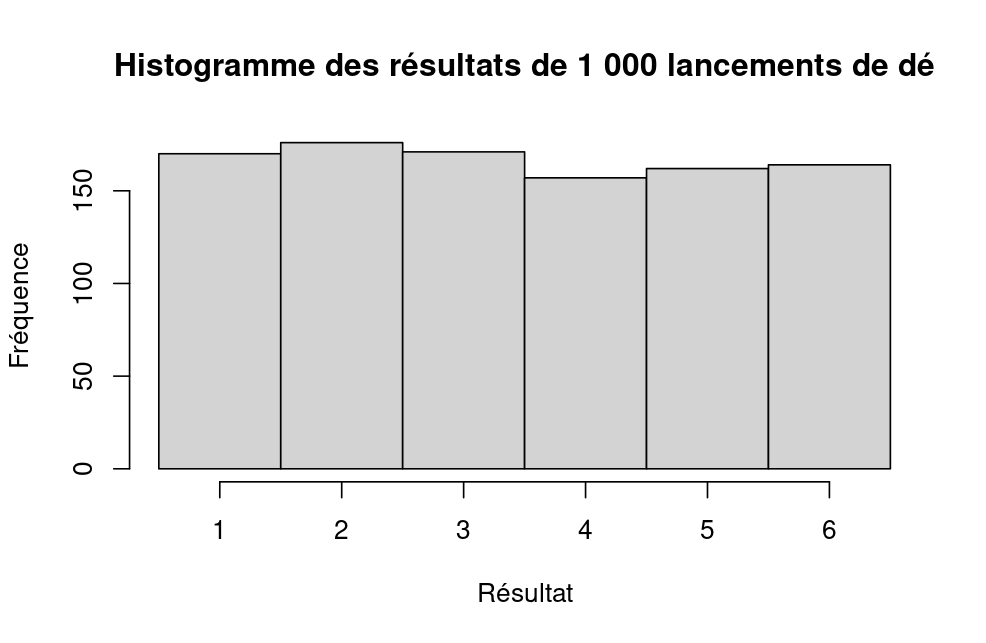

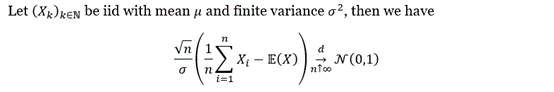

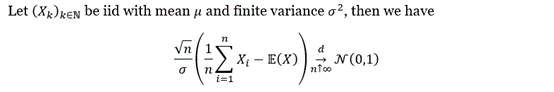

Let’s take a step back and have a look again at the Central Limit Theorem (CLT):

The CLT describes that the distribution of sample means approximates a normal distribution as the sample size gets larger. Similarly, the extreme value theory (EVT) studies the behavior of the extrema of samples.

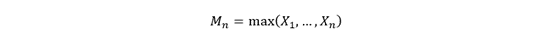

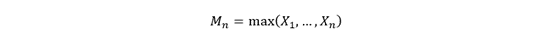

The block maximum is defined as such:

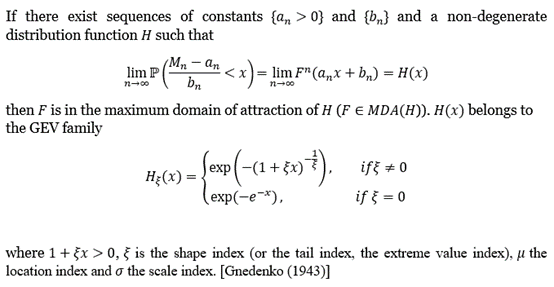

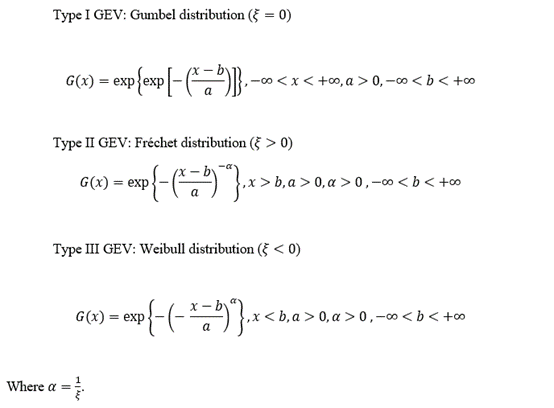

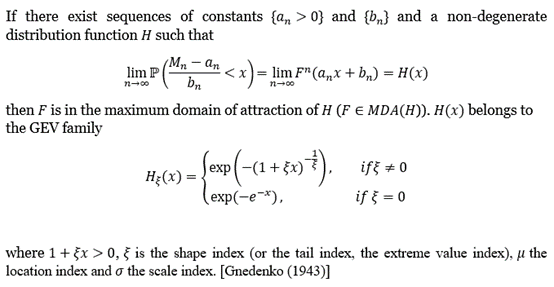

Generalized extreme value distribution (GEV)

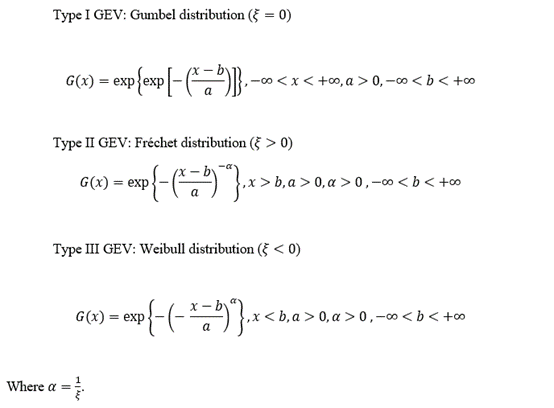

The GEV distributions have three subtypes corresponding to different tail feathers [von Misès (1936); Hosking et al. (1985)]:

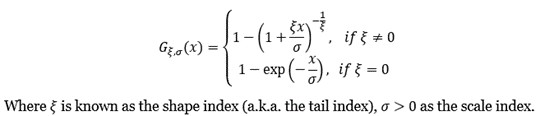

POT-GPD

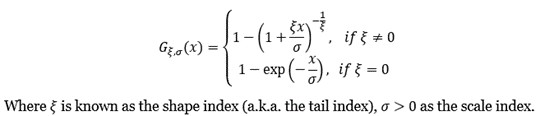

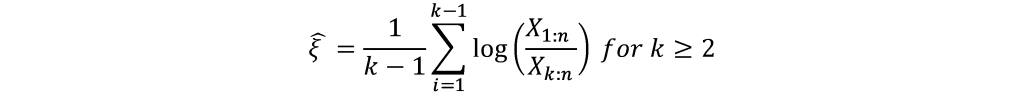

The block maxima approach is under reproach for its inefficiency and wastefulness of data usage, and it has been largely superseded in practice by the peak-over-threshold (POT) approach. The POT approach makes use of all data entries above a designated high threshold u. The threshold exceedances could be fitted into a generalized Pareto distribution (GPD):

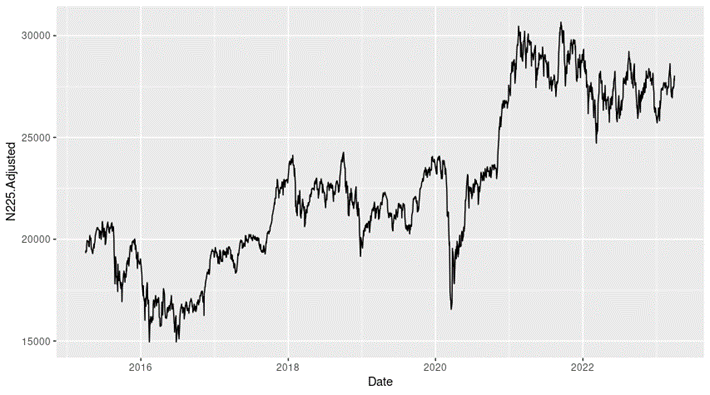

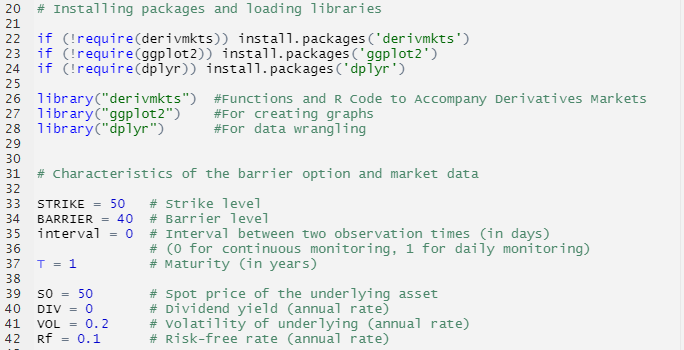

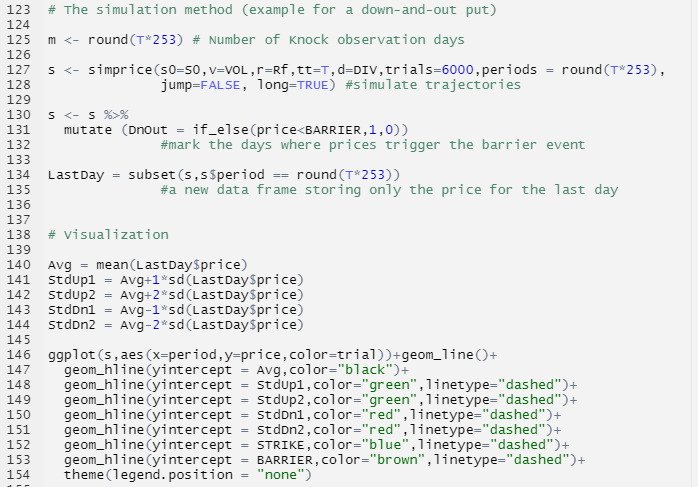

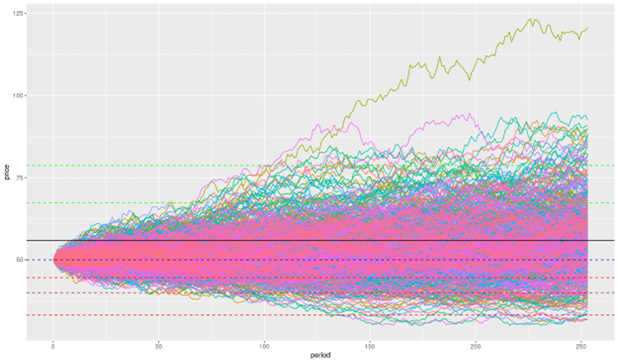

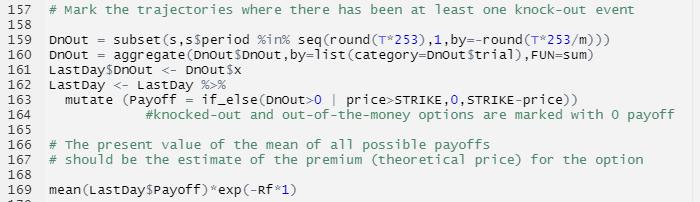

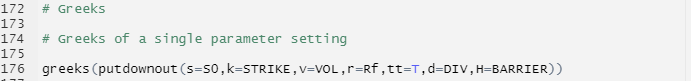

Illustration of Block Maxima and Peak-Over-Threshold approaches of the Extreme Value Theory with R

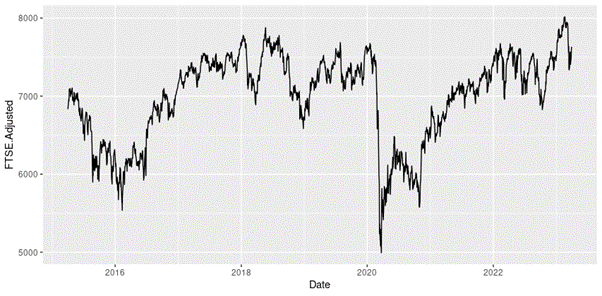

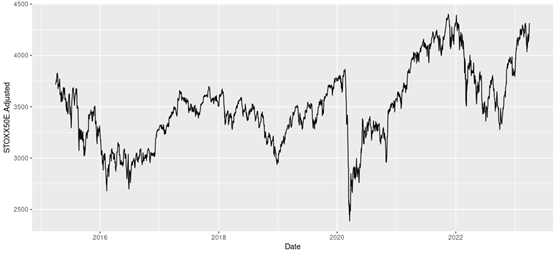

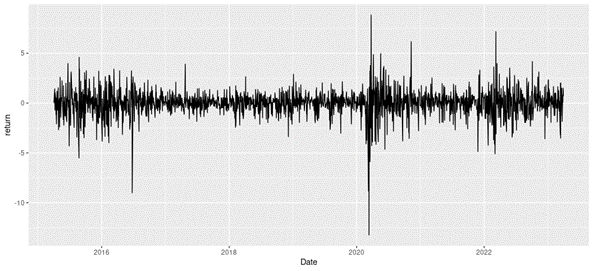

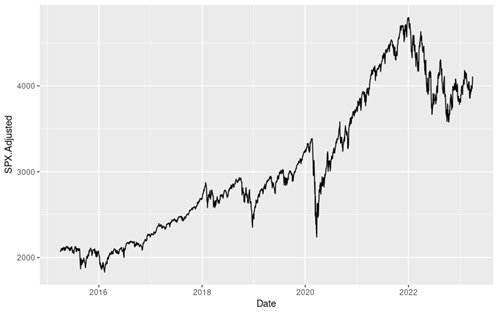

We now present an illustration of the two approaches of the extreme value theory (EVT), the block maxima with the generalized extreme value distribution (BM-GEV) approach and the peak-over-threshold with the generalized Pareto distribution (POT-GPD) approach, realized with R with the daily return data of the S&P 500 index from January 01, 1970, to August 31, 2022.

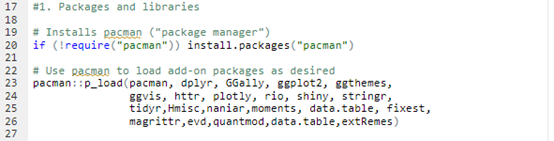

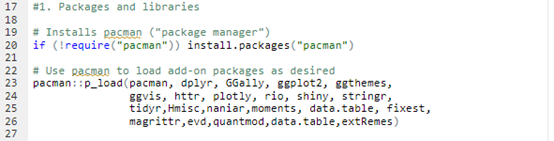

Packages and Libraries

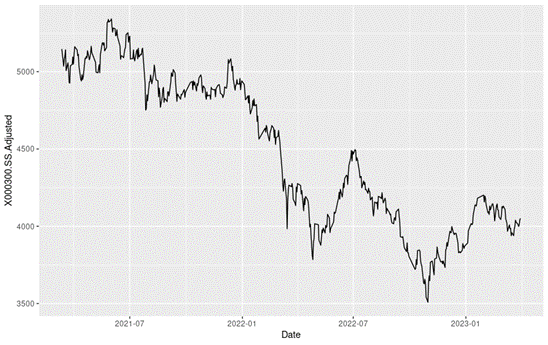

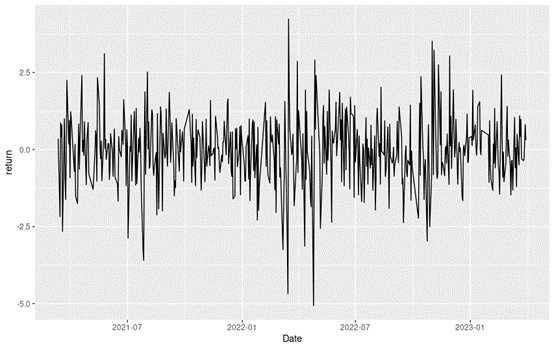

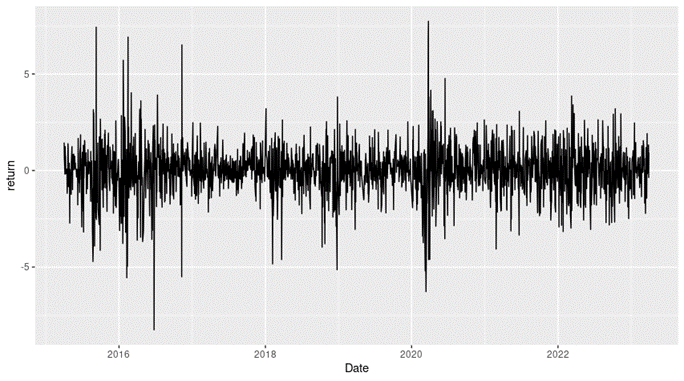

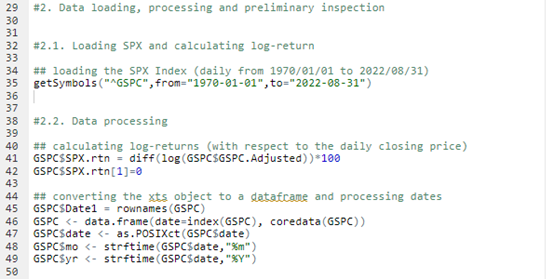

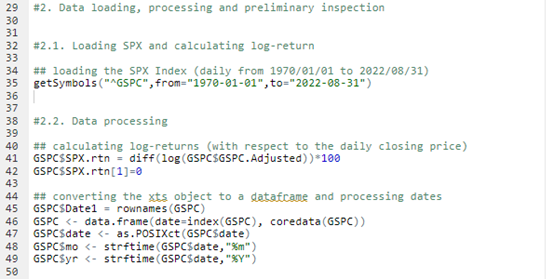

Data loading, processing and preliminary inspection

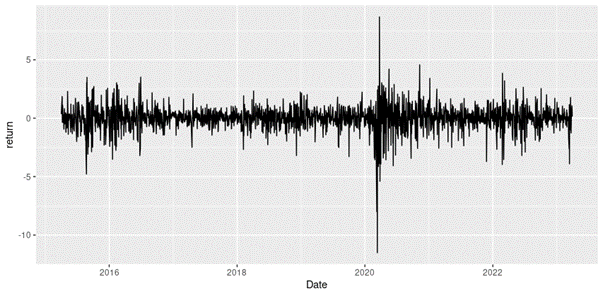

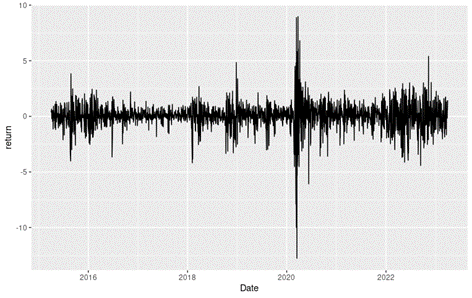

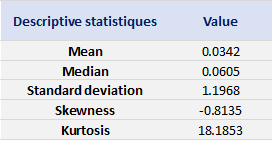

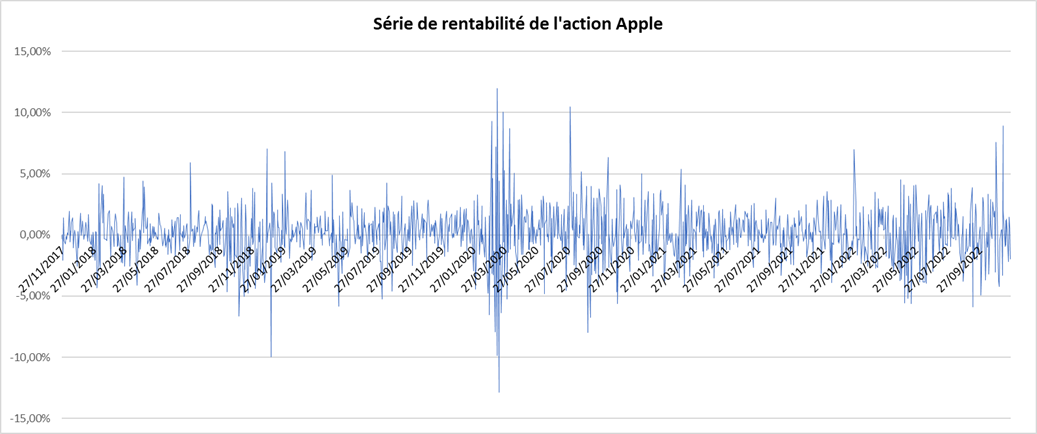

Loading S&P 500 daily closing prices from January 01, 1970, to August 31, 2022 and transforming the daily prices to daily logarithm returns (multiplied by 100). Month and year information are also extracted from later use.

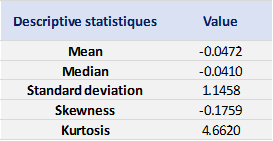

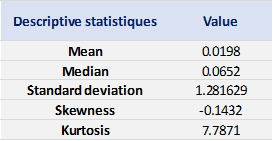

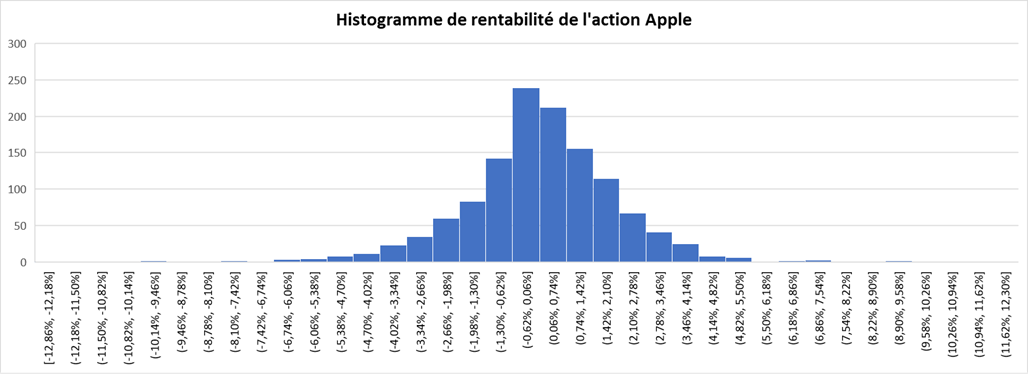

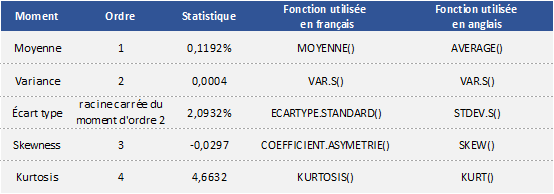

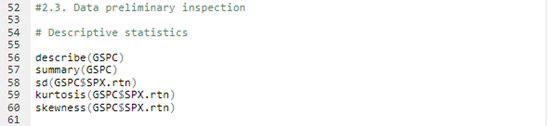

Checking the preliminary statistics of the daily logarithm series.

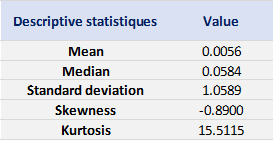

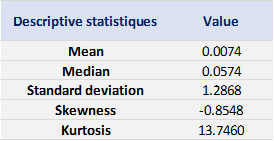

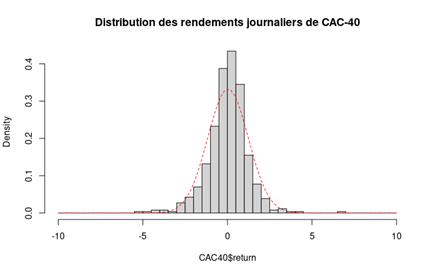

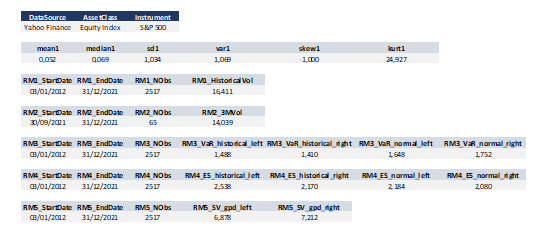

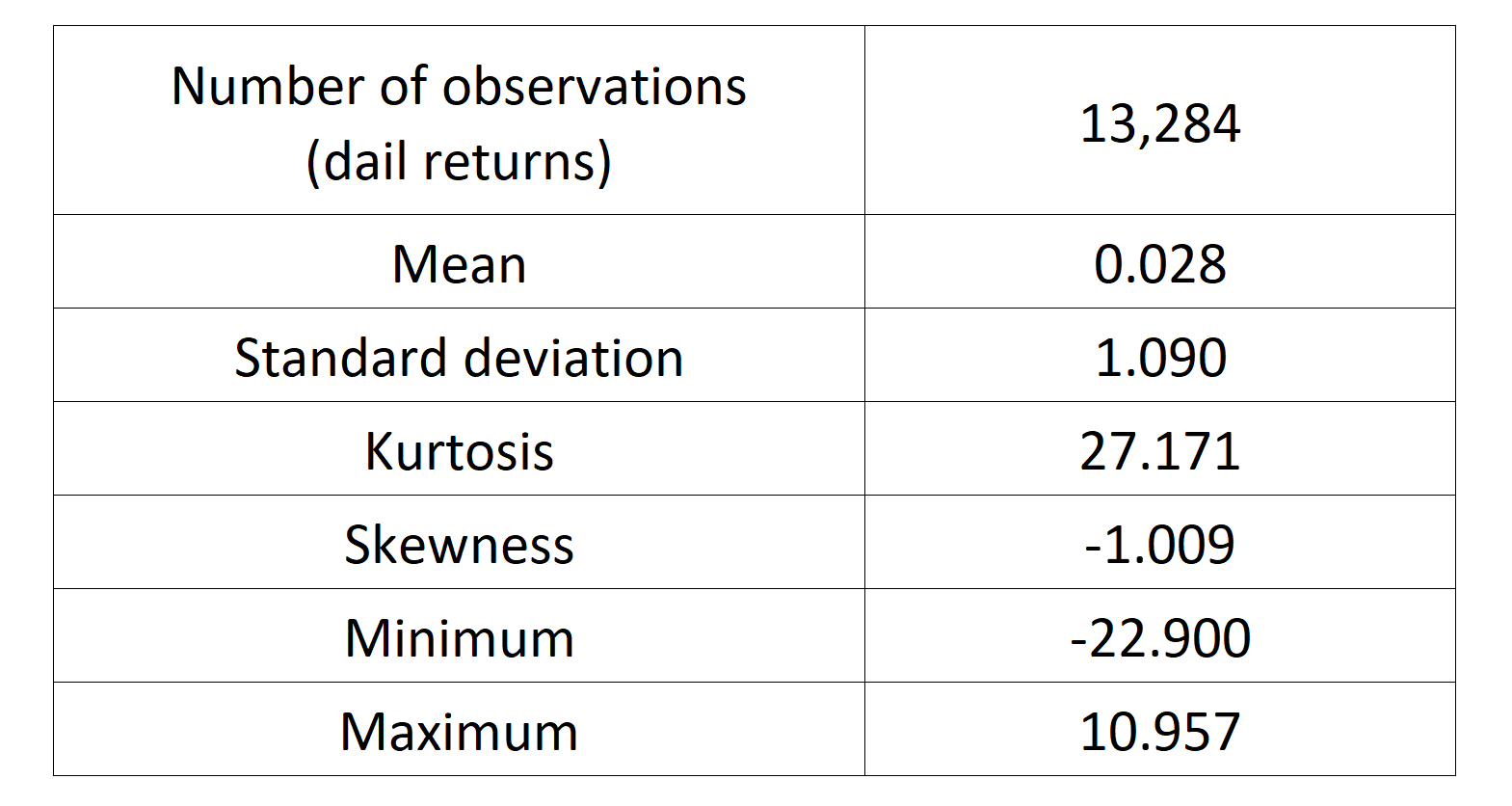

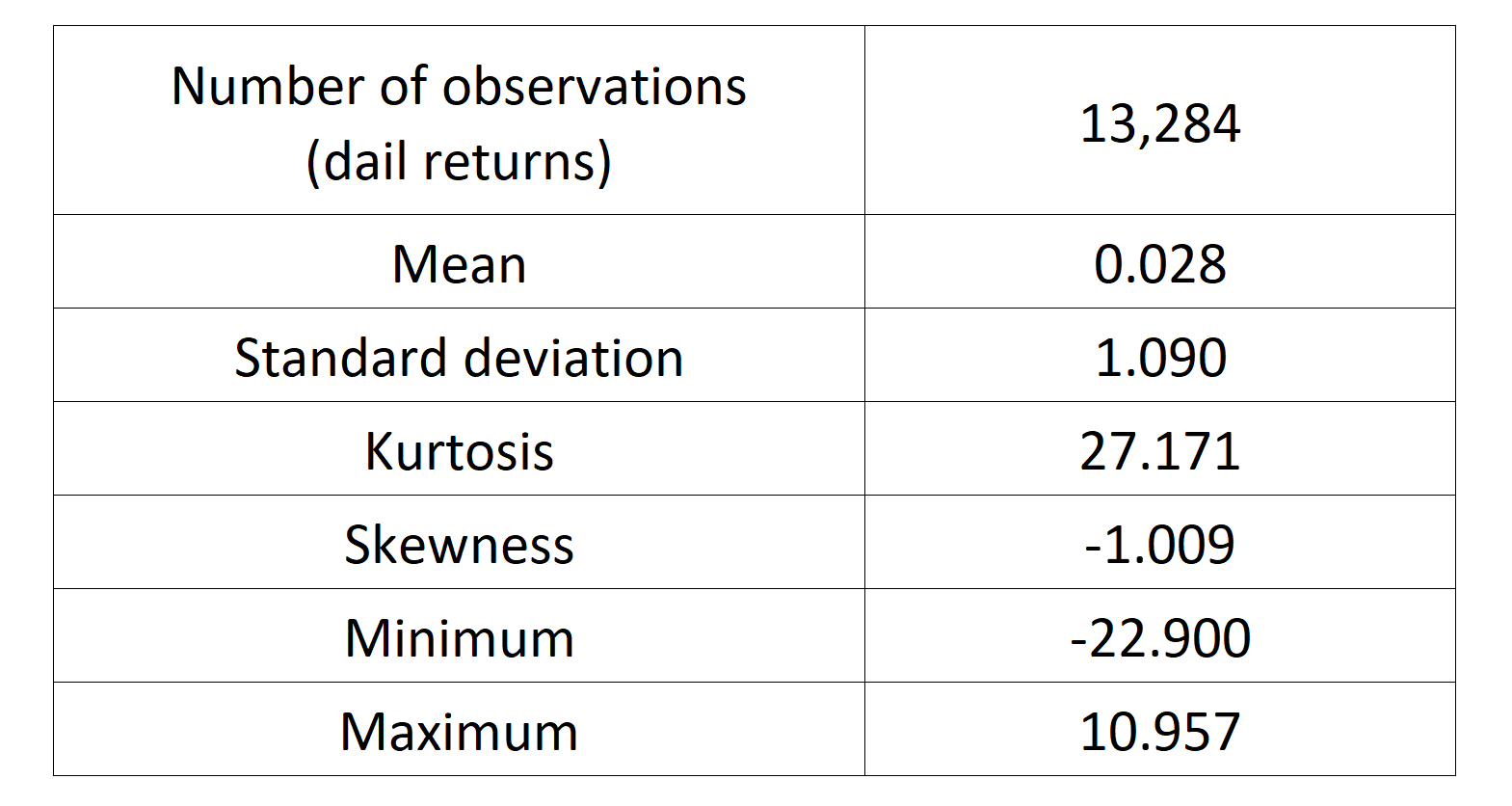

We can get the following basic statistics for the (logarithmic) daily returns of the S&P 500 index over the period from January 01, 1970, to August 31, 2022.

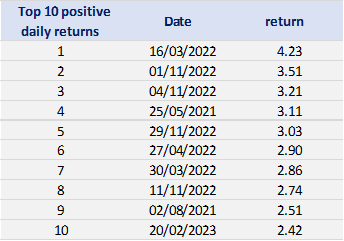

Table 1. Basic statistics of the daily return of the S&P 500 index.

Source: computation by the author.

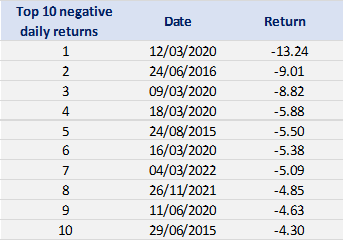

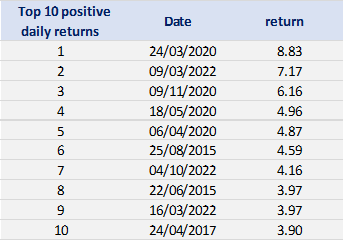

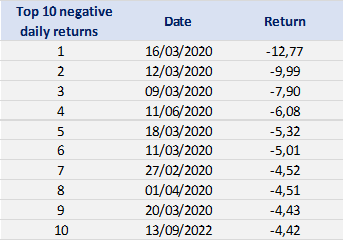

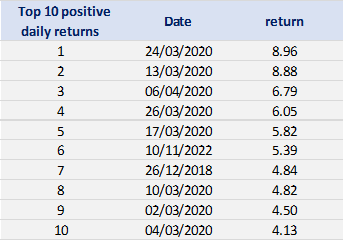

In terms of daily return, we can observe that the distribution is negatively skewed, which mean the negative tail is longer. The kurtosis is far higher than that of a normal distribution, which means that extreme outcomes are more frequent compared with a normal distribution. the minimum daily return is even more than twice of the maximum daily return, which could be interpreted as more prominent downside risk.

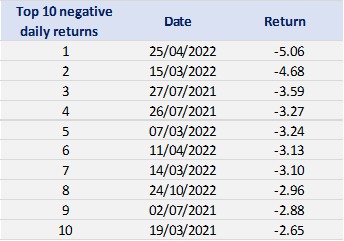

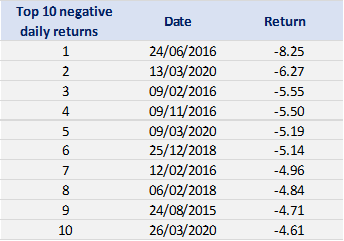

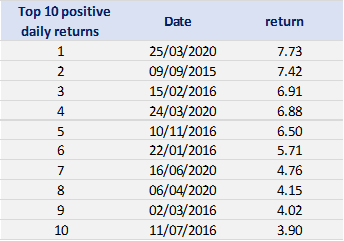

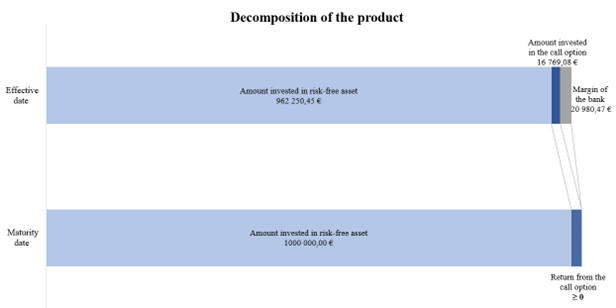

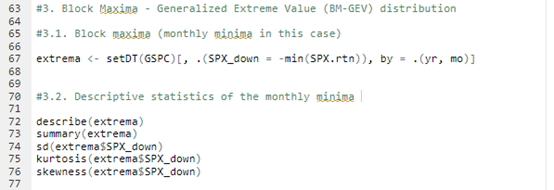

Block maxima – Generalized extreme value distribution (BM-GEV)

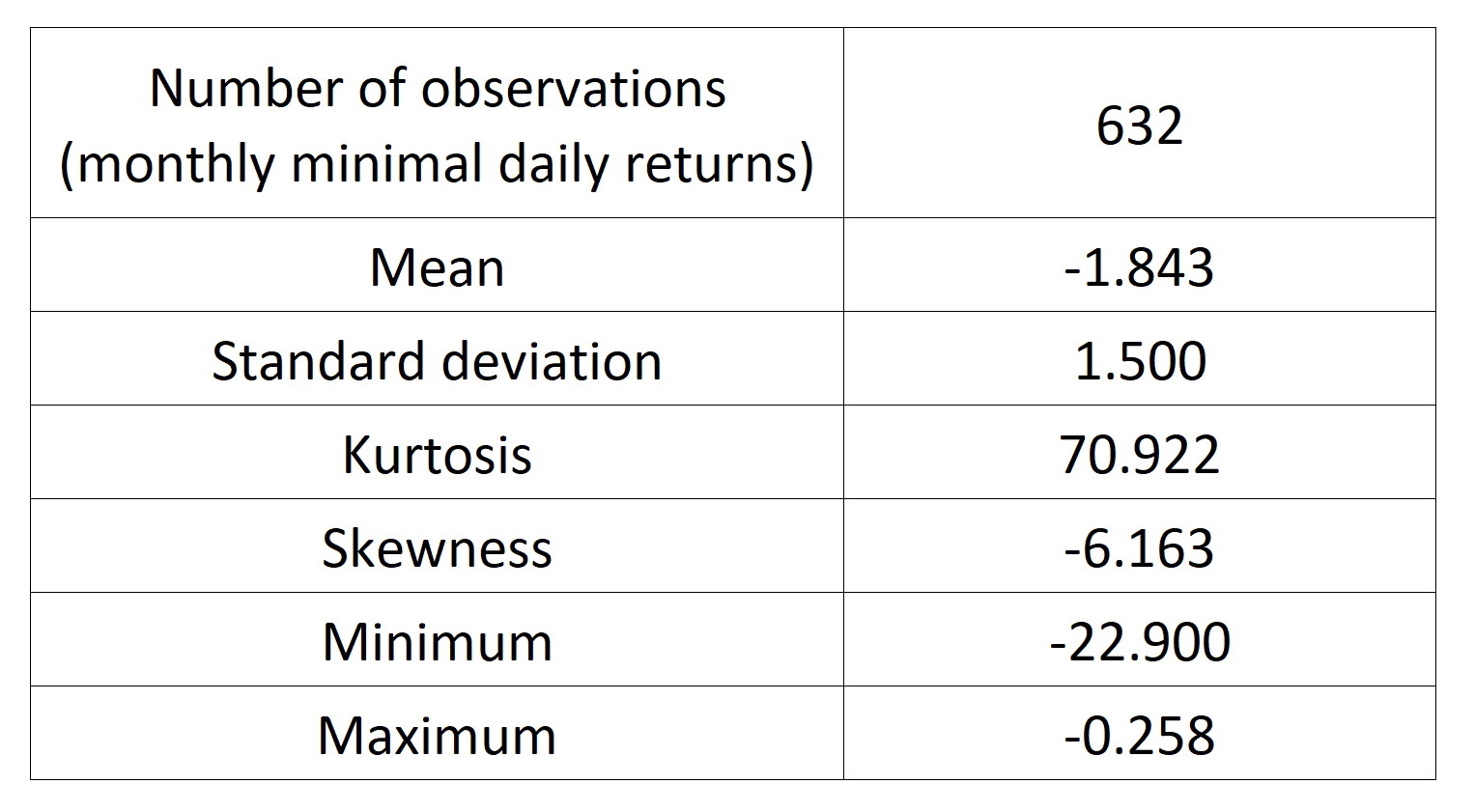

We define each month as a block and get the maxima from each block to study the behavior of the block maxima. We can also have a look at the descriptive statistics for the monthly downside extrema variable.

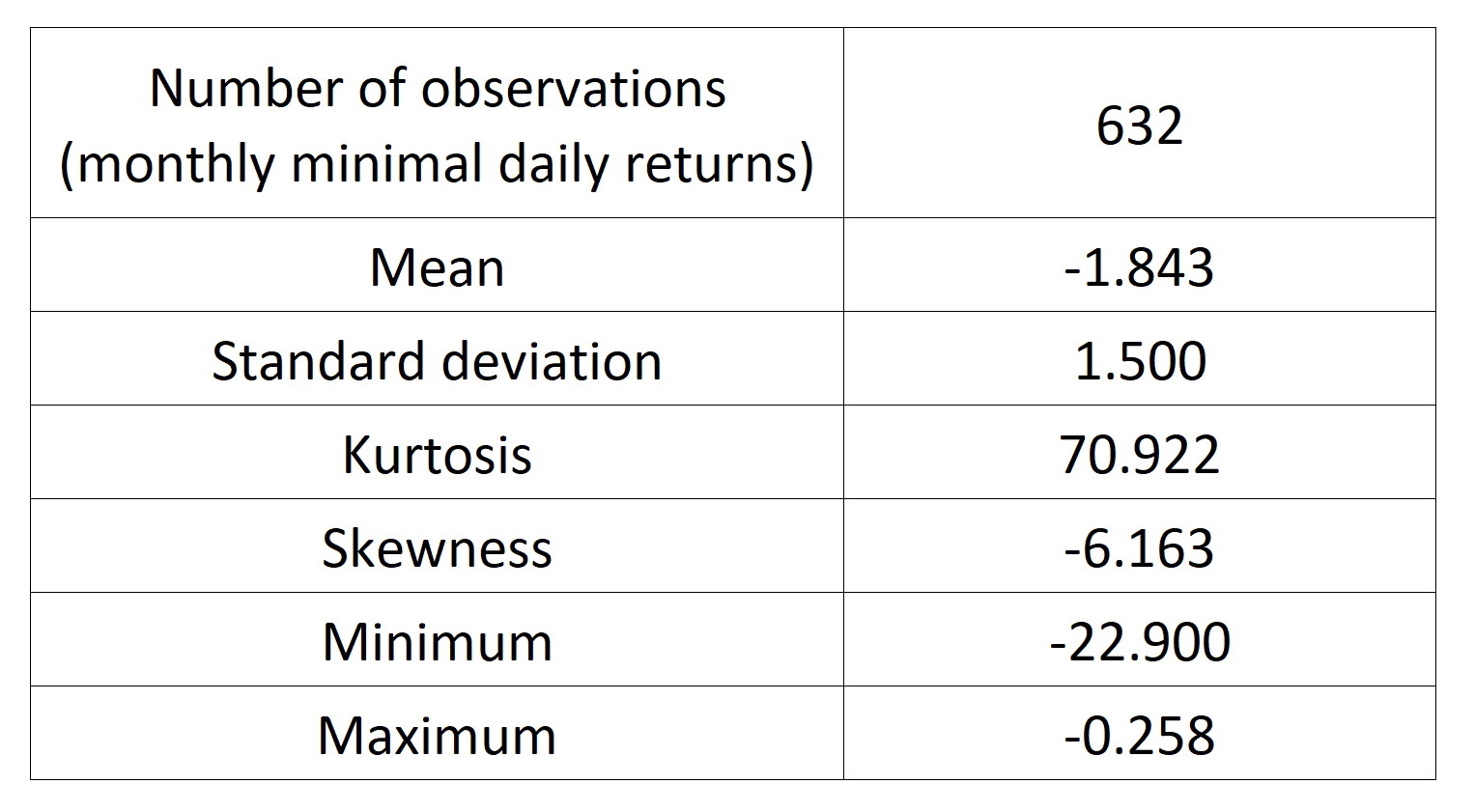

With the commands, we obtain the following basic statistics for the monthly minima variable:

Table 2. Basic statistics of the monthly minimal daily return of the S&P 500 index.

Source: computation by the author.

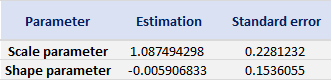

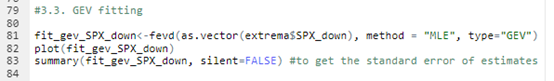

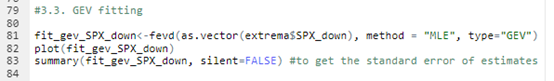

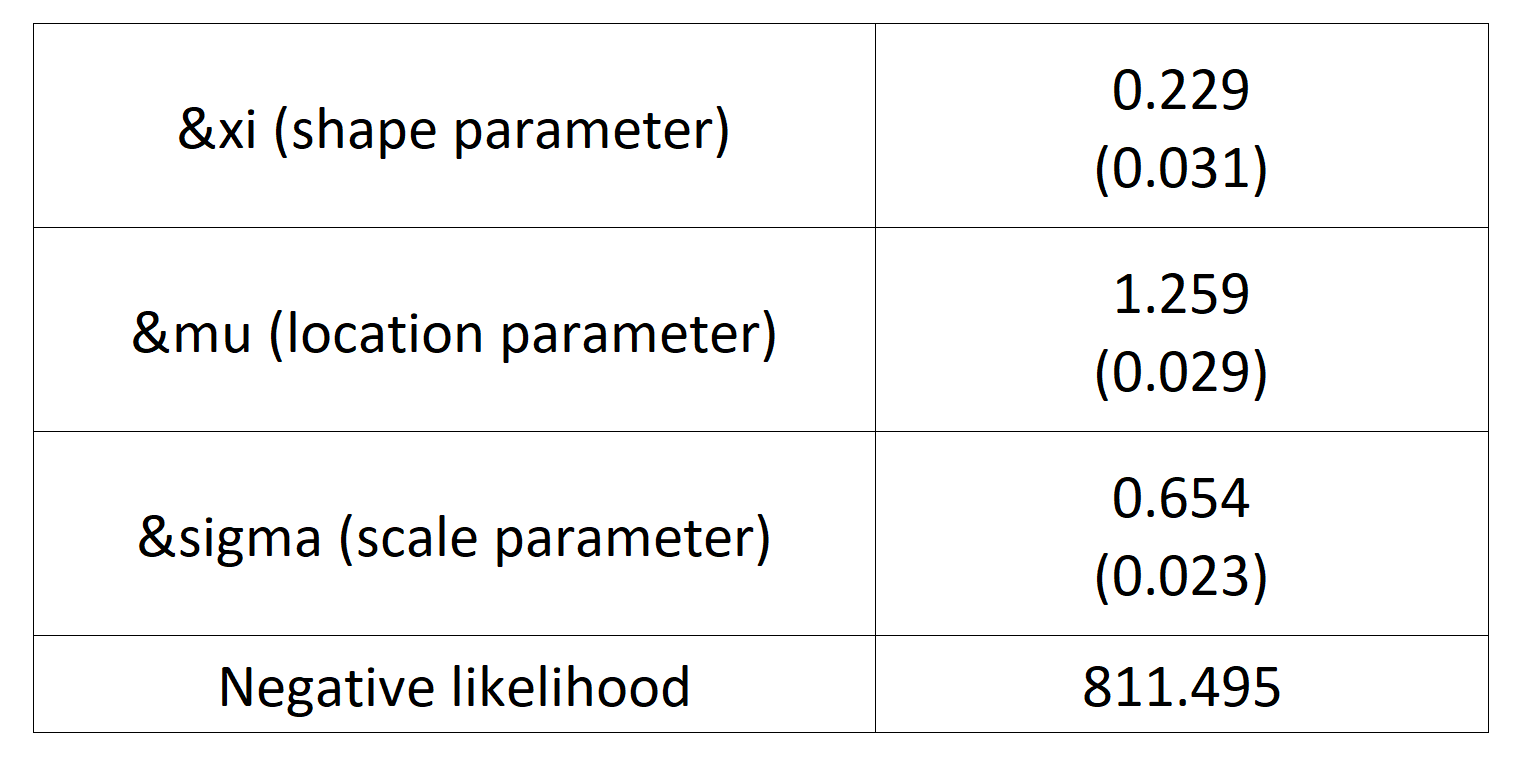

With the block extrema in hand, we can use the fevd() function from the extReme package to fit a GEV distribution. We can therefore get the following parameter estimations, with standard errors presented within brackets.

Table 3 gives the parameters estimation results of the generalized extreme value (GEV) for the monthly minimal daily returns of the S&P 500 index. The three parameters of the GEV distribution are the shape parameter, the location parameter and the scale parameter. For the period from January 01, 1970, to August 31, 2022, the estimation is based on 632 observations of monthly minimal daily returns.

Table 3. Parameters estimation results of GEV for the monthly minimal daily return of the S&P 500 index.

Source: computation by the author.

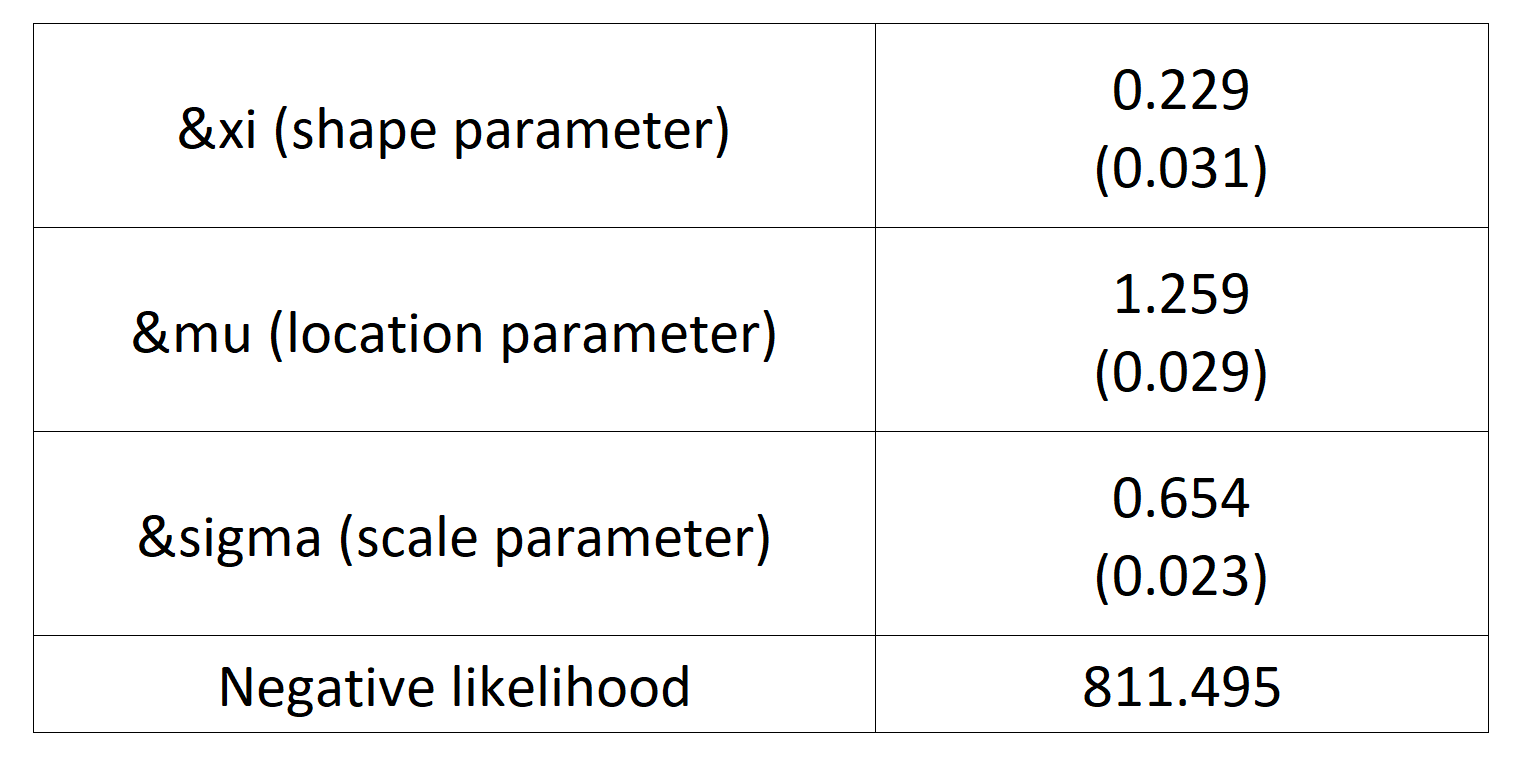

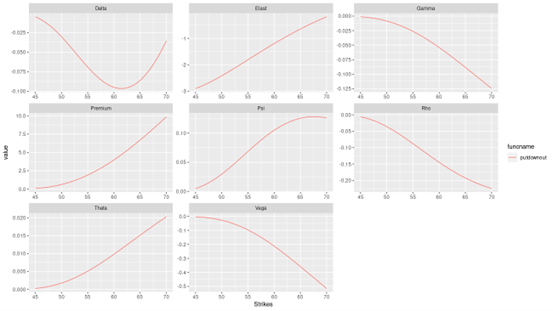

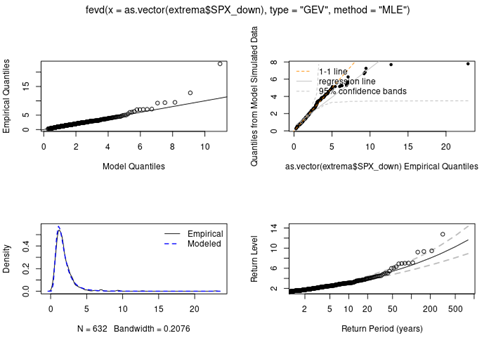

With the “plot” command, we are able to obtain the following diagrams.

- The top two respectively compare empirical quantiles with model quantiles, and quantiles from model simulation with empirical quantiles. A good fit will yield a straight one-to-one line of points and in this case, the empirical quantiles fall in the 95% confidence bands.

- The bottom left diagram is a density plot of empirical data and that of the fitted GEV distribution.

- The bottom right diagram is a return period plot with 95% pointwise normal approximation confidence intervals. The return level plot consists of plotting the theoretical quantiles as a function of the return period with a logarithmic scale for the x-axis. For example, the 50-year return level is the level expected to be exceeded once every 50 years.

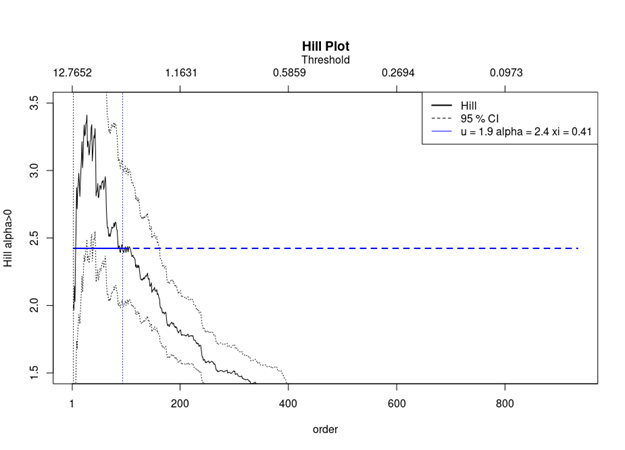

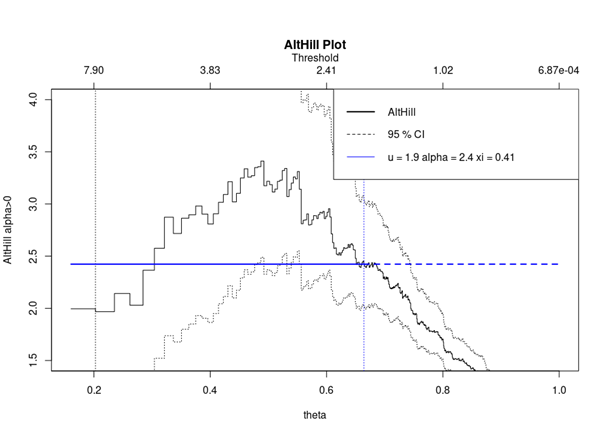

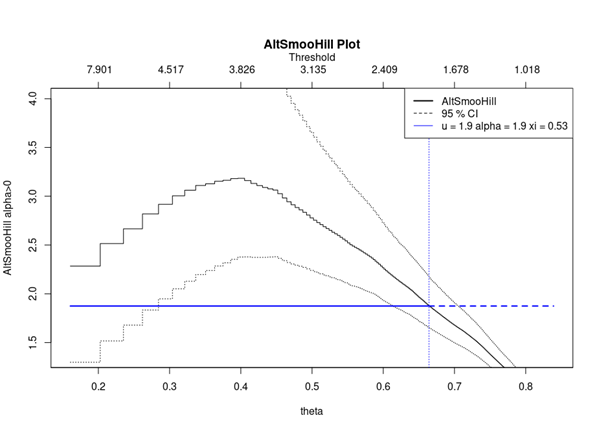

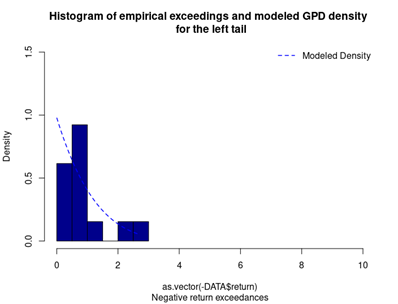

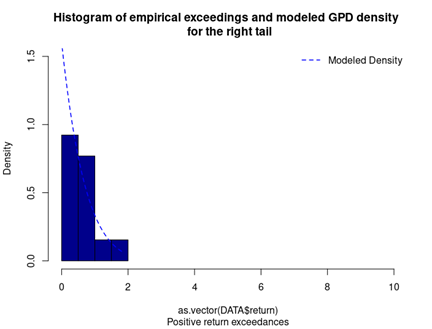

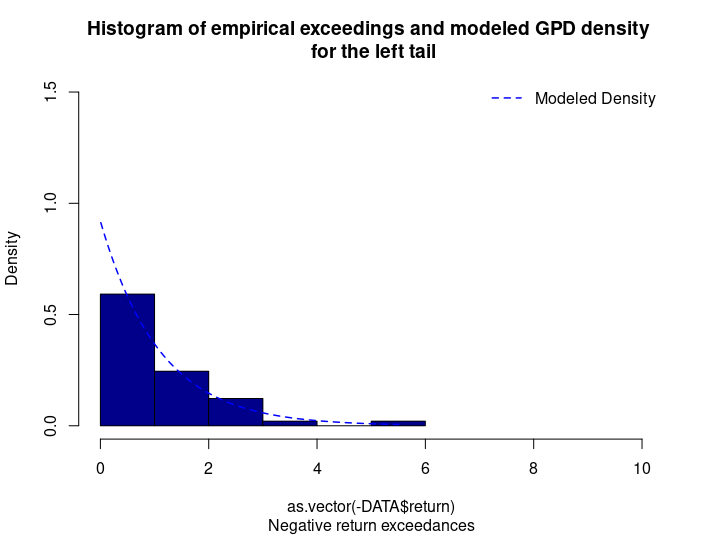

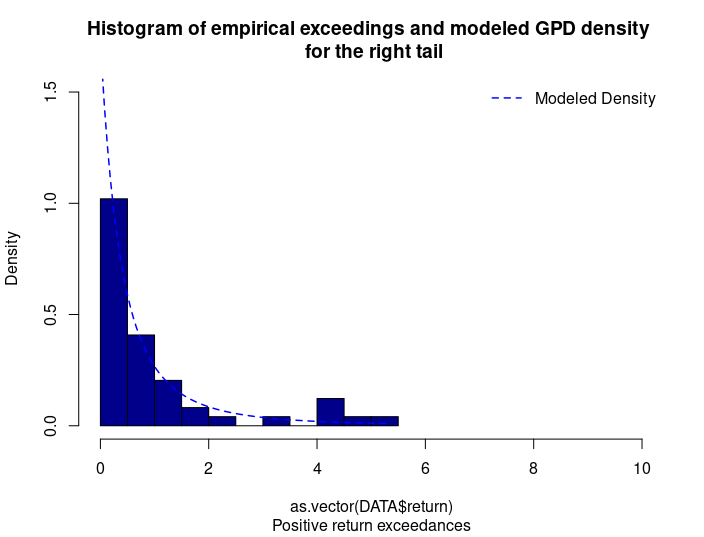

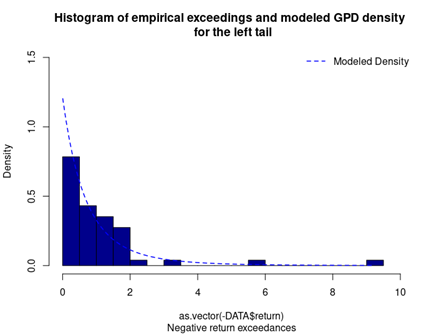

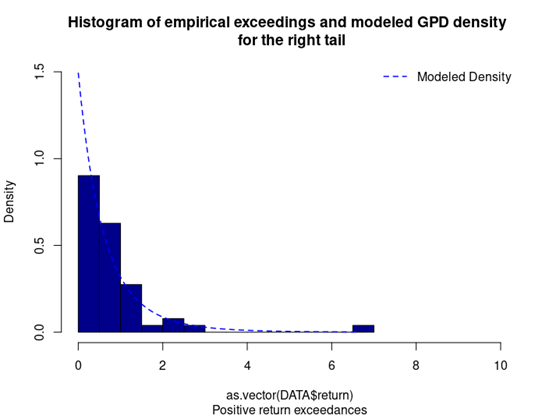

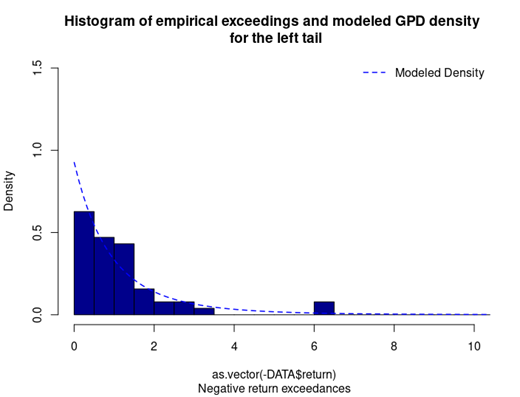

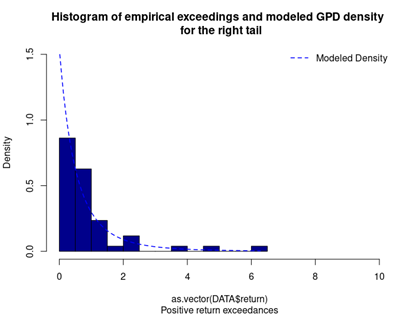

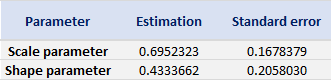

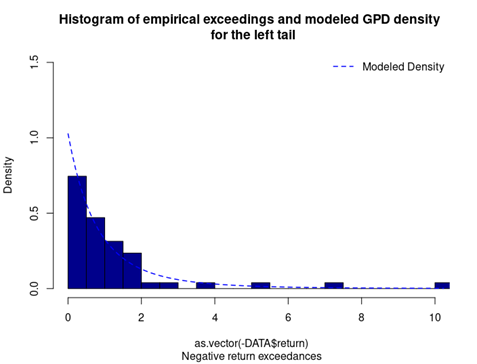

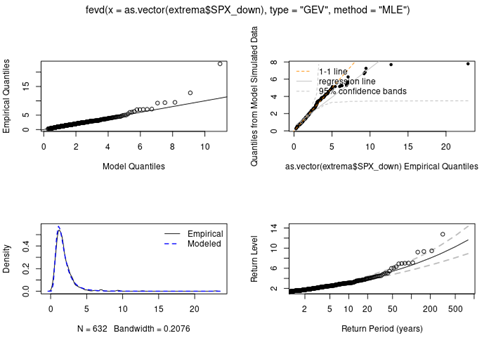

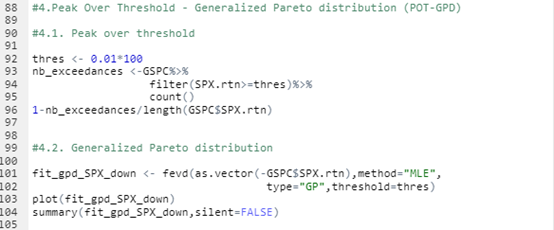

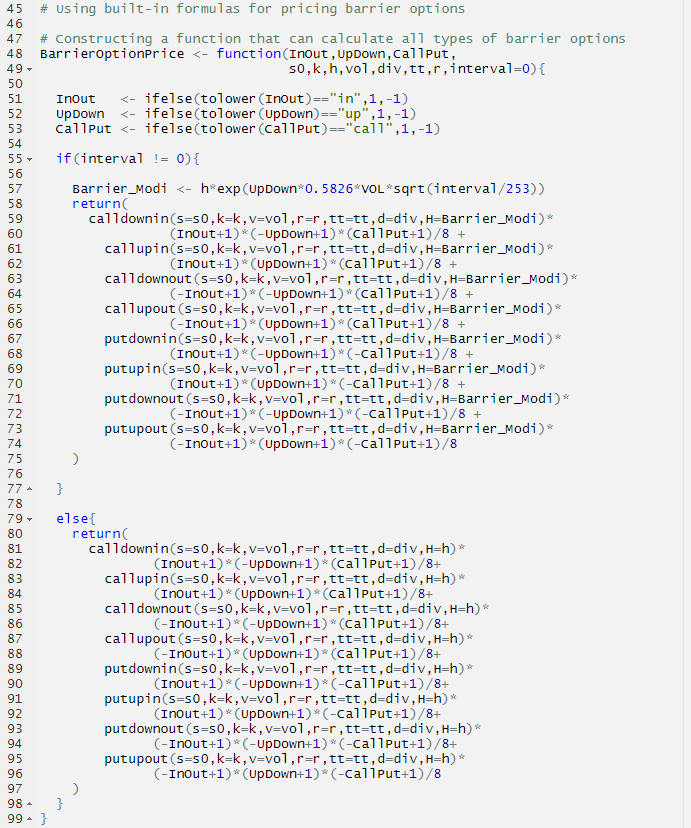

Peak over threshold – Generalized Pareto distribution (POT-GPD)

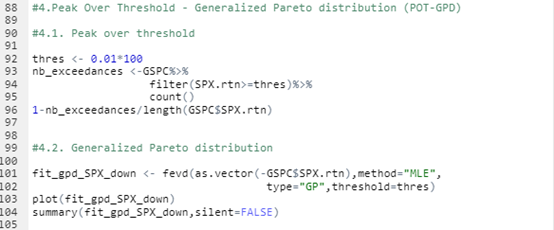

With respect to the POT approach, the threshold selection is central, and it involves a delicate trade-off between variance and bias where too high a threshold would reduce the number of exceedances and too low a threshold would incur a bias for poor GPD fitting (Rieder, 2014). The selection process could be elaborated in a separate post and here we use the optimal threshold of 0.010 (0.010*100 in this case since we multiply the logarithm return by 100) for stock index downside extreme movement proposed by Beirlant et al. (2004).

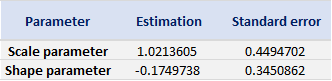

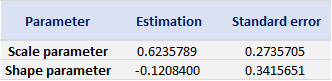

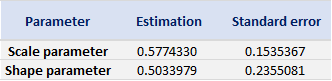

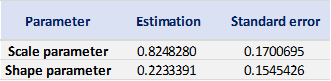

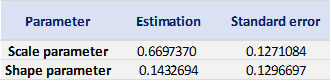

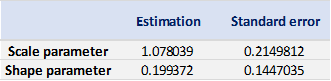

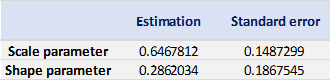

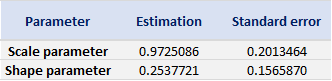

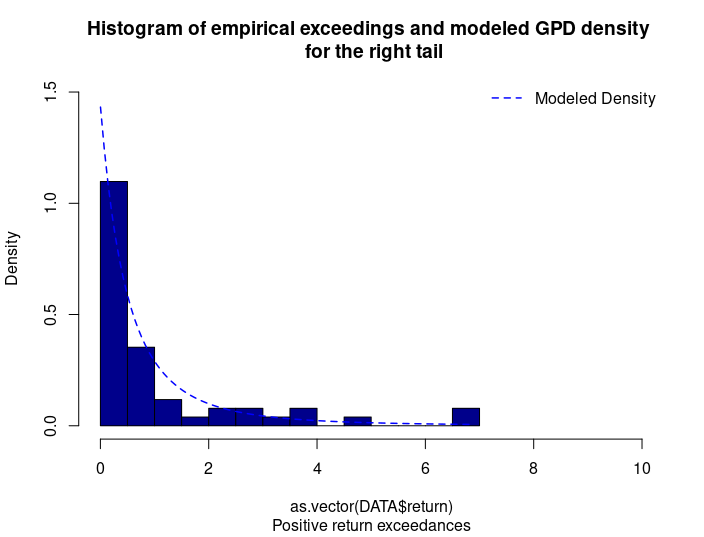

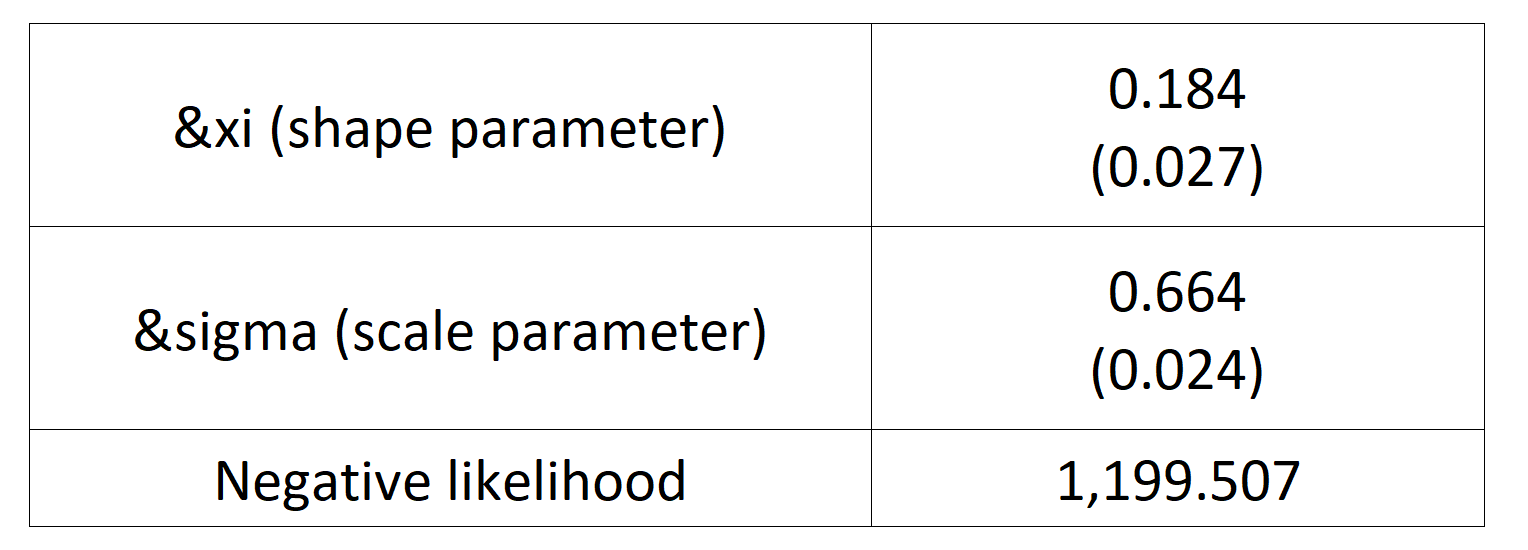

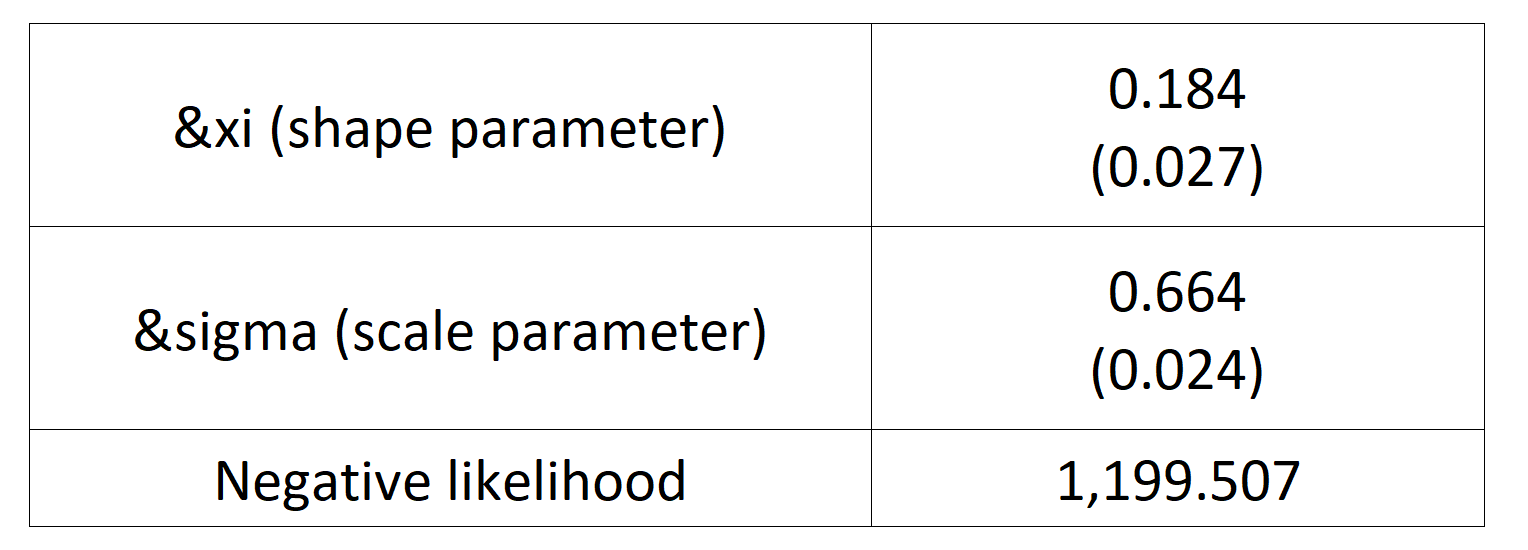

With the following commands, we get to fit the threshold exceedances to a generalized Pareto distribution, and we obtain the following parameter estimation results.

Table 4 gives the parameters estimation results of GPD for the daily return of the S&P 500 index with a threshold of -1%. In addition to the threshold, the two parameters of the GPD distribution are the shape parameter and the scale parameter. For the period from January 01, 1970, to August 31, 2022, the estimation is based on 1,669 observations of daily returns exceedances (12.66% of the total number of daily returns).

Table 4. Parameters estimation results of the generalized Pareto distribution (GPD) for the daily return negative exceedances of the S&P 500 index.

Source: computation by the author.

Download R file to understand the BM-GEV and POT-GPD approaches

You can find below an R file (file with txt format) to understand the BM-GEV and POT-GPD approaches.

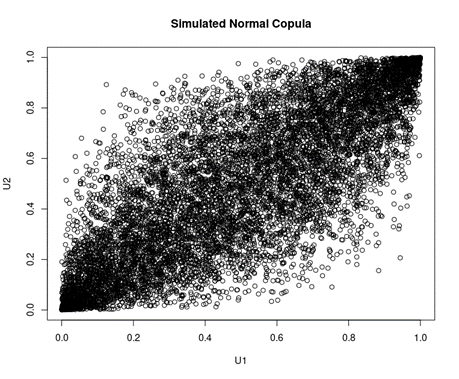

Why should I be interested in this post

Financial crises arise alongside disruptive events such as pandemics, wars, or major market failures. The 2007-2008 financial crisis has been a recent and pertinent opportunity for market participants and academia to reflect on the causal factors to the crisis. The hindsight could be conducive to strengthening the market resilience faced with such events in the future and avoiding dire consequences that were previously witnessed. The Gaussian copula, a statistical tool used to manage the risk of the collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) that triggered the flare-up of the crisis, has been under serious reproach for its essential flaw to overlook the occurrence and the magnitude of extreme events. To effectively understand and cope with the extreme events, the extreme value theory (EVT), born in the 19th century, has regained its popularity and importance, especially amid the financial turmoil. Capital requirements for financial institutions, such as the Basel guidelines for banks and the Solvency II Directive for insurers, have their theoretical base in the EVT. It is therefore indispensable to be equipped with knowledge in the EVT for a better understanding of the multifold forms of risk that we are faced with.

Related posts on the SimTrade blog

▶ Shengyu ZHENG Optimal threshold selection for the peak-over-threshold approach of extreme value theory

▶ Gabriel FILJA Application de la théorie des valeurs extrêmes en finance de marchés

▶ Shengyu ZHENG Extreme returns and tail modelling of the S&P 500 index for the US equity market

▶ Nithisha CHALLA The S&P 500 index

Resources

Academic research (articles)

Aboura S. (2009) The extreme downside risk of the S&P 500 stock index. Journal of Financial Transformation, 2009, 26 (26), pp.104-107.

Gnedenko, B. (1943). Sur la distribution limite du terme maximum d’une série aléatoire. Annals of mathematics, 423–453.

Hosking, J. R. M., Wallis, J. R., & Wood, E. F. (1985) “Estimation of the generalized extreme-value distribution by the method of probability-weighted moments” Technometrics, 27(3), 251–261.

Longin F. (1996) The asymptotic distribution of extreme stock market returns Journal of Business, 63, 383-408.

Longin F. (2000) From VaR to stress testing : the extreme value approach Journal of Banking and Finance, 24, 1097-1130.

Longin F. et B. Solnik (2001) Extreme correlation of international equity markets Journal of Finance, 56, 651-678.

Mises, R. v. (1936). La distribution de la plus grande de n valeurs. Rev. math. Union interbalcanique, 1, 141–160.

Pickands III, J. (1975). Statistical Inference Using Extreme Order Statistics. The Annals of Statistics, 3(1), 119– 131.

Academic research (books)

Embrechts P., C. Klüppelberg and T Mikosch (1997) Modelling Extremal Events for Insurance and Finance.

Embrechts P., R. Frey, McNeil A. J. (2022) Quantitative Risk Management, Princeton University Press.

Gumbel, E. J. (1958) Statistics of extremes. New York: Columbia University Press.

Longin F. (2016) Extreme events in finance: a handbook of extreme value theory and its applications Wiley Editions.

Other materials

Extreme Events in Finance

Rieder H. E. (2014) Extreme Value Theory: A primer (slides).

About the author

The article was written in October 2022 by Shengyu ZHENG (ESSEC Business School, Grande Ecole Program – Master in Management, 2020-2023).