Discovering the Secrets of a Bank Trading Room

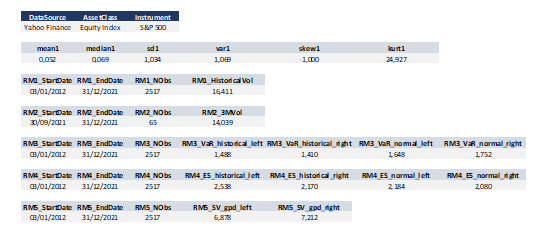

In this article, David GONZALEZ (ESSEC Business School, Global BBA, 2023-2024) delves into the amazing yet often concealed aspects that frequently transpire within different bank trading rooms. This investigation is rooted in his experiences at Banco Industrial y de Comercio Exterior (BICE).

BICE Bank

BICE Bank was founded in 1979 in Santiago, Chile, under the name Banco Industrial y de Comercio Exterior by a significant group of Chilean investors associated with some of the country’s leading export companies. Currently, BICE Bank has focused on providing services to high-income individuals in Chile. Currently, it is the seventh-highest commercial bank in Chile.

Logo of the company.

Source: the company.

My Internship at BICE

Ever since I was young, I have been drawn to the financial markets. This was the primary reason that led me to select a nine-month internship in the Market Risk and Liquidity division, a component of the trading room at BICE Bank. My primary responsibility was to provide daily reports on various risk indicators to the trading room, with a particular emphasis on highlighting the changes resulting from different trades conducted during the day. In the following paragraphs, I will provide a brief overview of some of the main indicators I was tasked with explaining, after that, I am going to talk about some interesting things that every aspiring trader should know about this business.

The risk indicators that I was in charge of

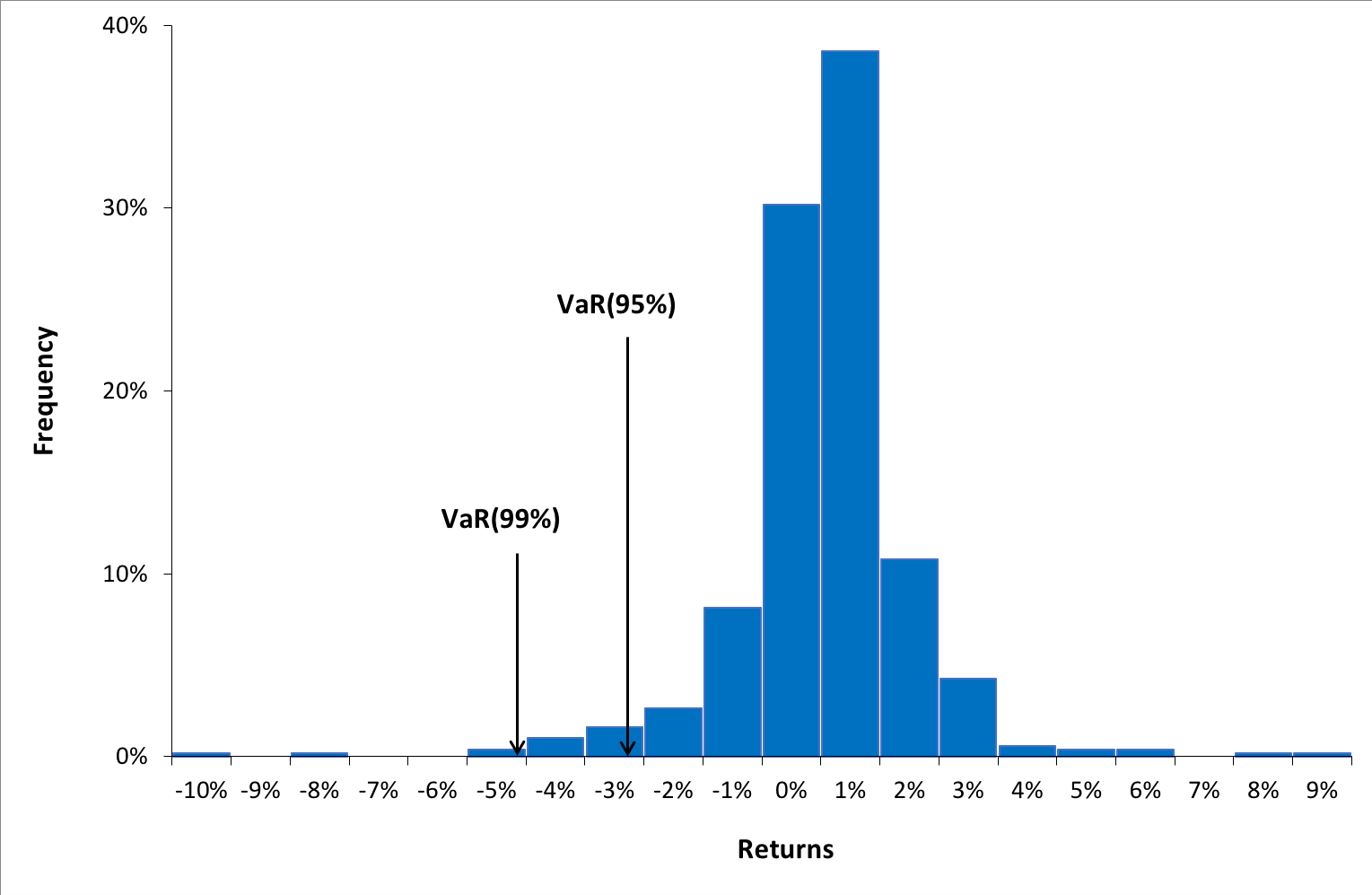

Value at Risk (VaR)

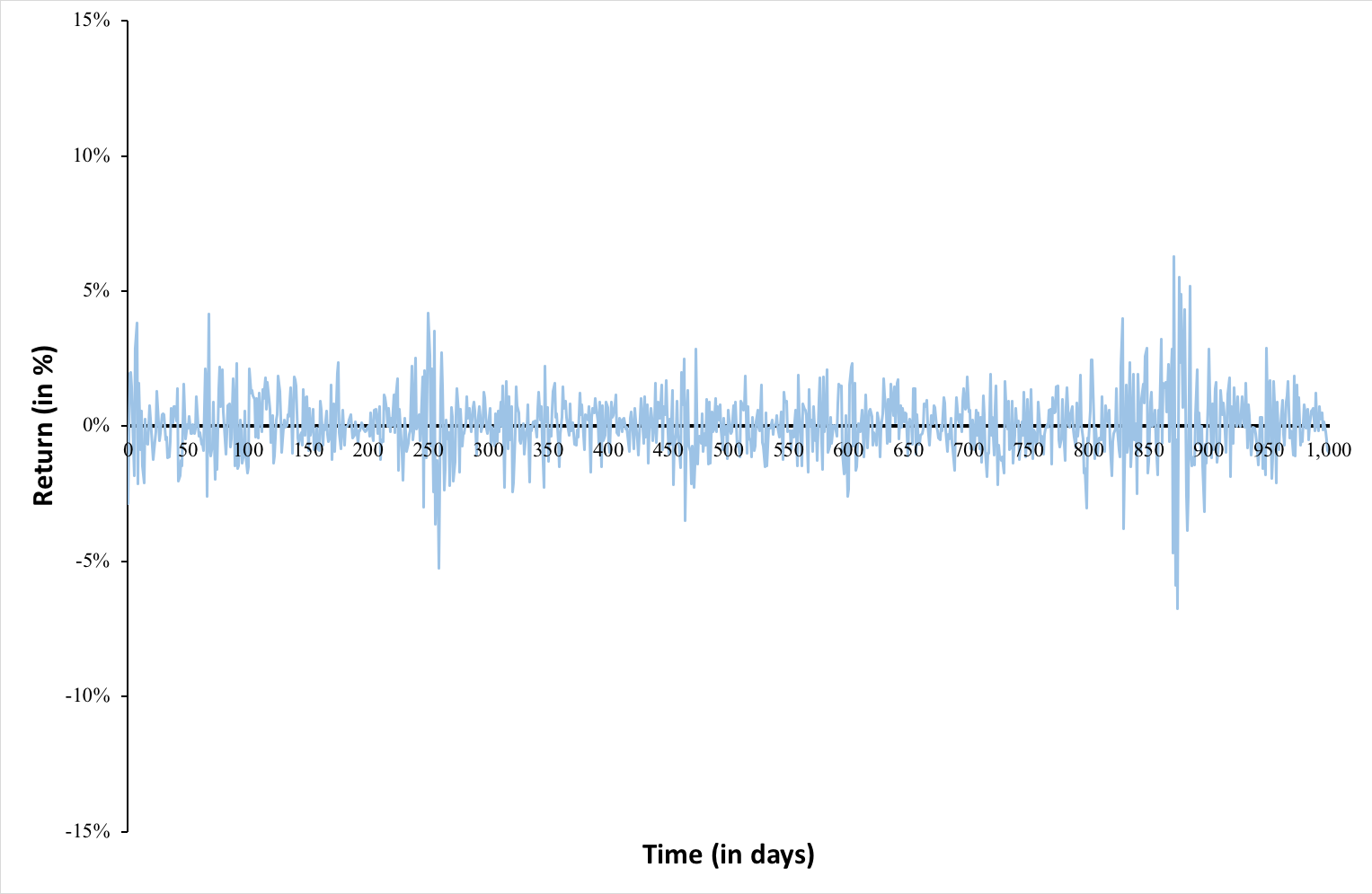

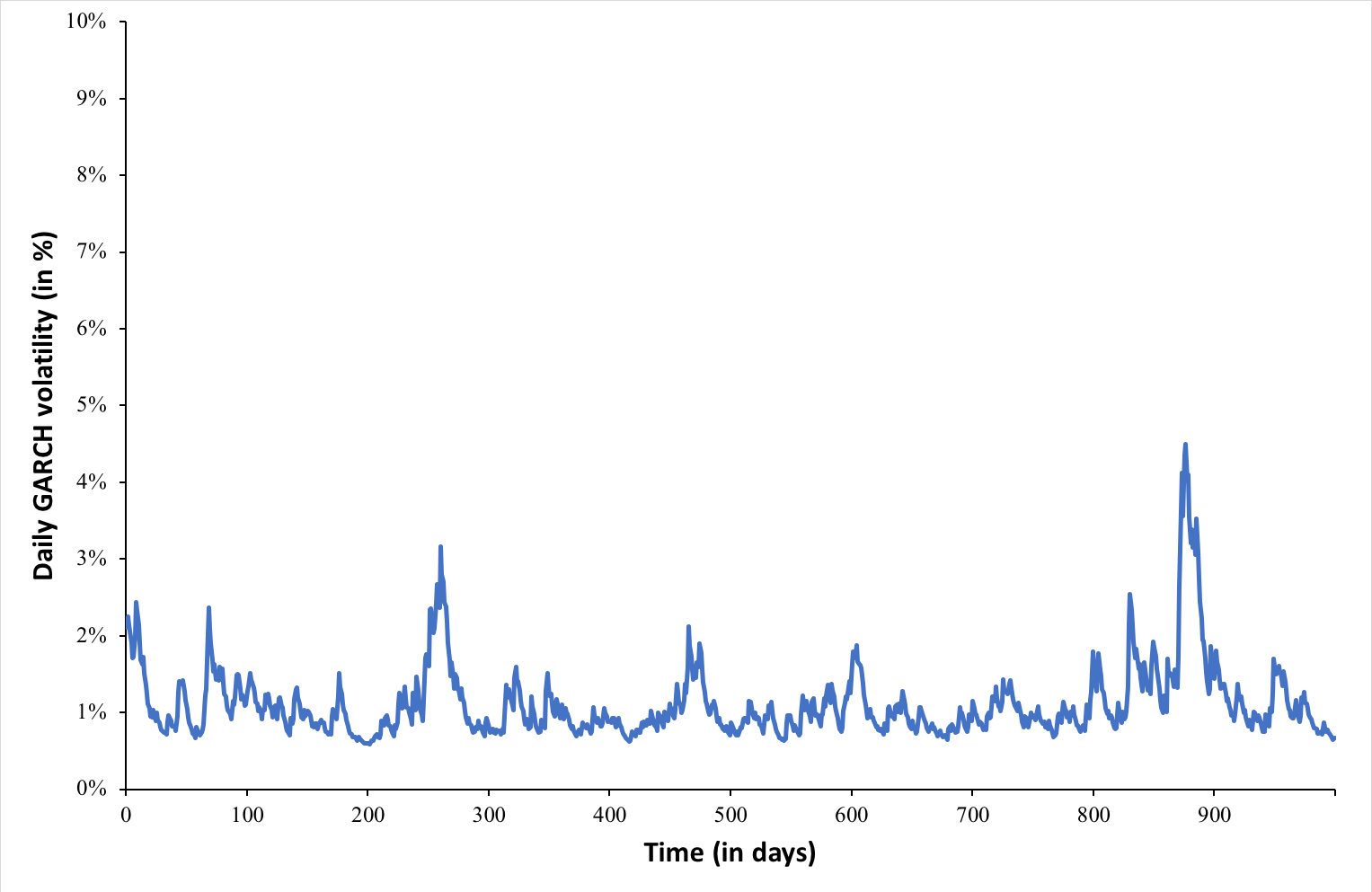

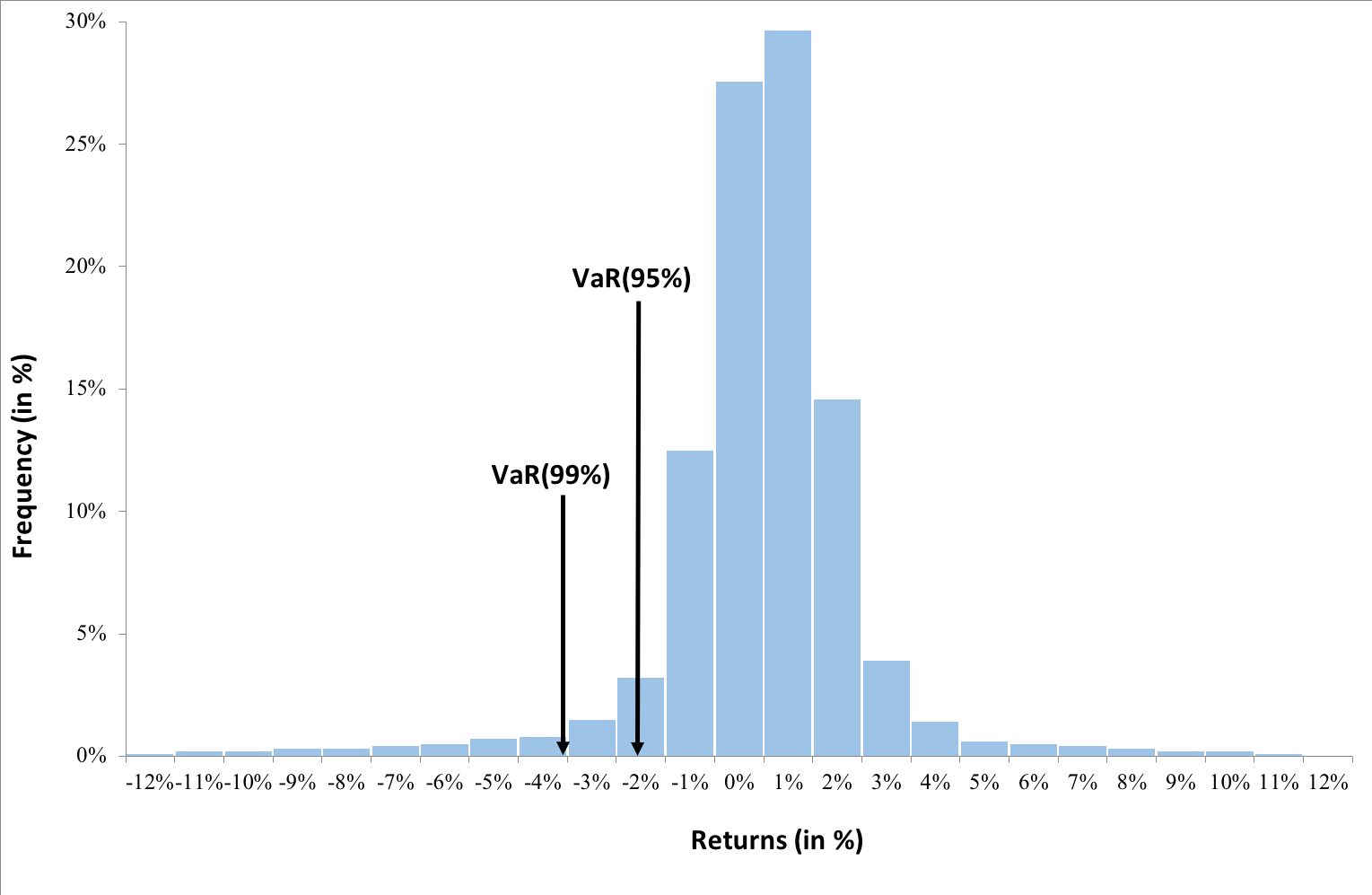

This indicator aims to quantify the worst-case scenario of losses in the bank’s portfolio, taking into account historical market data. In other words, it provides an estimate of the likely amount of money the portfolio could lose in a day of financial crisis (a stress scenario).

Present Value of 1 Basis Point (PV01)

This indicator seeks to quantify the potential loss in the portfolio resulting from a one-basis-point increase in interest rates. It is important to note that this indicator is applicable only to fixed-income assets, as it attempts to predict the change in the value of a bullet bond that is dependent on interest rate fluctuations.

Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR)

Have you ever heard of interbank loans? This indicator is of paramount importance to bankers as it assesses whether the bank possesses sufficient liquidity as required by regulatory standards or even for normal day-to-day operations. If the LCR falls below a certain threshold, the bank may need to enter into arrangements with a counterparty to borrow funds and restore this indicator to compliance.

Credit Value Adjustment (CVA)

Have you ever heard of the over-the-counter (OTC) market? Unlike centralized exchanges that guarantee the money or assets being traded, the OTC market lacks such centralized assurance. Banks frequently engage in OTC transactions, and the primary means by which they protect themselves against counterparty risk is through CVA. This is computed based on the credit rating of the counterparty. The CVA indicator reveals the bank’s exposure in relation to the counterparties with whom it conducts transactions.

Required skills and knowledge

In general, large trading rooms not only trade on the stock exchange, which is widely known, but they also engage in transactions in the over-the-counter (OTC) market. It was crucial for me to understand how this market operates, including what a swap is, what a forward contract entails, and how interest rates and inflation expectations influence the financial market. This knowledge was essential because I needed to stay informed about how macroeconomic factors or new transactions affected the bank’s portfolio. Every move in each risk indicator had to make economic or financial sense before being reported to the traders.

As for soft skills, effective communication when required was clearly important. Maintaining composure and seeking solutions rather than assigning blame when issues arose at work were vital skills as well. Furthermore, the ability to proactively seek solutions independently before seeking assistance from someone who might be occupied with their own tasks was crucial.

What just few people know (knowing the business)

Understanding Different Types of Trading Rooms: A Crucial Insight for Aspiring Traders

When I started working at BICE Bank, my boss told me that the bank had two trading rooms: one of them was the main trading room of the bank, and the other was the trading room of the stockbrokerage (which is a subsidiary of the bank). Obviously, this didn’t make sense to me, and I wondered, what is the reason for having two different trading rooms on two different floors of the building? When I expressed this concern to my boss, he explained, “It’s because they are oriented towards different sides. The main trading room focuses on the buy side, which means that traders manage, invest, and build portfolios while seeking returns within the risk level stipulated by the risk department. Usually, hedge funds, banks, insurance companies, and pension funds have this emphasis.” He continued, “The other trading room is part of the stockbrokerage, which is a subsidiary of this bank. They focus on the sell side. In this case, traders are responsible for executing transactions for clients who use our brokerage service. In other words, these traders don’t make decisions; they simply follow clients’ orders. Examples of this side include investment banks, brokerage firms, and market makers.”

Future traders must be clear on which side of the market they want to be on, so they can choose the right path for their careers. If the goal is to build their own portfolio and invest based on their own analyses and expectations, while assuming a higher level of risk, the trader should opt for the buy side. Conversely, if the aim is to avoid the risk of losses associated with maintaining a personal portfolio and only focus on achieving the best prices in the market, the sell side is the preferable choice. In this scenario, all the risk would be borne by the clients, as the trader would merely act as an intermediary between them and the market.

Financial concepts related my internship

The trader who triumphed over the 2008 crisis (Risks)

During my tenure at the bank, I had the privilege of meeting several senior traders, most of whom had over 20 years of experience in the market. One of them shared a fascinating story about how he navigated through the 2008 crisis.

Banks typically maintain a rather conservative investment policy, meaning they are risk averse. Consequently, one of the most common strategies is securities arbitrage (buying securities in a market where they are undervalued and selling them in other more expensive market). This strategy carries zero exposure, and profits are guaranteed when operating with substantial sums of money. This particular trader happened to be engaged in arbitrage on the day the 2008 financial crisis erupted. Upon realizing the unfolding catastrophe, he promptly closed his long positions remaining the shorts, that resulting in astronomical profits at a time when the global economy was collapsing.

Future traders looking to be on the buy side need to consider which financial institution is the best for advancing their career. Hedge funds, commercial banks, insurance companies, and pension fund managers tend to differ in terms of risk tolerance, either due to their own institutional policies or regulatory guidelines. For instance, in Chile, the regulatory commission does not allow commercial banks to invest in stocks.

Why a Chilean bank is concerned about federal reserve FED (Interest rates)

I had the fortune of gaining my experience at this bank during a period when the Fed and most central banks worldwide were raising their interest rates as a measure to control inflation stemming from the expansive policies implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic. I noticed that the traders were always closely monitoring the Fed’s announcements and whether they aligned with market expectations.

Intrigued by the heightened anticipation surrounding the market, I decided to seek insight from one of the traders. He offered the following explanation: “There are several factors contributing to this heightened attention. Primarily, monetary policy decisions in an inflationary environment tend to shape our trading strategies. On one hand, rate hikes affect all fixed-income assets, potentially causing our portfolio to depreciate in value and elevating risk indicators like VaR. Additionally, when the Federal Reserve tends to raise interest rates, it becomes more profitable for institutional investors to purchase bonds due to the relatively low levels of risk premium and liquidity premium demanded. Lastly, we also consider short positions in emerging market currencies since the dollar typically appreciates in the midst of Fed rate hikes.”

Federal Reserve announcements typically tend to influence financial markets. This is mainly because they shed light on the current state of the economy, enabling institutional investors to assess whether it is more profitable to invest in fixed income or equities. This assessment considers the risk premium and liquidity premium demanded from assets.

Liquidity the most important but the most avoided for banks (Banks Liquidity)

Every Monday afternoon, we held our weekly meeting where the latest developments were reported to the company’s top executives, including the CEO. During one such meeting, the bank’s CEO noticed that the bank’s liquidity indicators were quite comfortable, indicating an ample reserve of funds in the bank’s coffers.

Normally, customer deposits do not remain dormant in their accounts; instead, this money is put to use for investments or lent to other customers. Hence, the surplus liquidity captured the CEO’s attention. In the end, money entails a trade-off, and maintaining it in reserve can prove rather costly. The CEO raised a query regarding this with the head of the trading room, who clarified that the excess liquidity was a result of the impending release of the decision on whether to change the Chilean constitution or not, anticipated for that week. In anticipation of an adverse outcome, the trading room needed to uphold substantial liquidity to accommodate depositors wishing to withdraw their funds. The head of the trading room confirmed that, indeed, maintaining such high liquidity levels cost millions each day since interest rates were exceedingly high and the funds could have been invested. Nevertheless, this course of action was deemed necessary in light of the country’s political crisis.

Why should I be interested in this post?

Are you interested in pursuing a career in a trading room? Do you aspire to become a trader one day? If the answer is yes, you must read this post. By doing so, you will gain insights into how trading rooms operate and the various types of trading rooms available in the marketplace. Additionally, you will learn about some important concepts in finance, accompanied by an interesting story to introduce them.

Related posts on the SimTrade blog

Professional experiences

▶ All posts about Professional experiences

▶ Tanguy TONEL All posts about Professional experiences

▶ Shengyu ZHENG My experience as Actuarial Apprentice at La Mutuelle Générale

▶ Akshit GUPTA My apprenticeship experience within client services at BNP Paribas

Financial products

▶ Federico DE ROSSI Understanding the Order Book: How It Impacts Trading

▶ Alexandre VERLET Understanding financial derivatives: options

▶ Alexandre VERLET Understanding financial derivatives: futures

▶ Alexandre VERLET Understanding financial derivatives: swaps

▶ Alexandre VERLET Understanding financial derivatives: forwards

Useful resources

Hull J.C. (2021) Options, Futures, and Other Derivatives Pearson, 11th Edition.

Banco BICE (2022) Memoria Anual.

About the author

The article was written in December 2023 by David Gonzalez (ESSEC Business School, Grande Ecole Program – Global BBA, 2023-2024).