In this article, Saral BINDAL (Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur, Metallurgical and Materials Engineering, 2024-2028 & Research assistant at ESSEC Business School) explains how the business of derivatives markets has evolved over time and the pivotal role of the Black–Scholes–Merton option pricing model in their development.

Introduction

The derivatives market is among the most dynamic segments of global finance, serving as a tool for risk management, speculation, and price discovery across diverse asset classes. Spanning from bespoke over-the-counter contracts to standardized exchange-traded instruments, derivatives have become indispensable for investors, institutions, and corporations alike.

This post explores the derivatives landscape, examining market structures, contract types, underlying assets, and key statistics of business activity. It also highlights the pivotal role of the Black–Scholes–Merton model, which provided a theoretical framework for options pricing and catalysed the growth of derivatives markets.

Types of derivatives markets

The derivatives market can be categorized according to their market structure (over-the-counter derivatives and exchange-traded derivatives), the types of derivatives contracts traded (futures/forward, options, swaps), and the underlying asset classes involved (equities, interest rates, foreign exchange, commodities, and credit), as outlined below.

Market structure: over-the-counter derivatives and exchange-traded derivatives

Over-the-counter derivatives are privately negotiated, customized contracts between counterparties like banks, corporates, and hedge funds, traded via phone or electronic networks. OTC derivatives offer high flexibility in terms (price, maturity, quantity, delivery) but are less regulated, with decentralized credit risk management, no central clearing, low price transparency, and higher counterparty risk. They suit specialized or low-volume trades and often incubate new products.

Exchange-traded derivatives are standardized contracts traded on organized exchanges with publicly reported prices. Trades are cleared through a central clearing house that guarantees settlement, with daily marking-to-market and margining to reduce counterparty risk. ETDs are more regulated, transparent, and liquid, making them ideal for high-volume, widely traded instruments, though less flexible than OTC contracts.

Types of derivatives contracts

A derivative contract is a financial instrument that derives its values from an underlying asset. The four major types of such instruments are explained below.

A forward contract is a private agreement to buy or sell an asset at a fixed future date and price. It is traded over the counter between two counterparties (e.g., banks or clients). One party takes a long position (agrees to buy), the other a short position (agrees to sell). Settlement happens only at maturity, and contracts are customized, unregulated, and expose parties to direct counterparty risk.

A futures contract has the same economic purpose as a forward, future delivery at a fixed price, but is traded on an exchange with standardized terms. A clearing house stands between buyers and sellers and guarantees performance. Futures are marked to market daily so gains and losses are realized continuously. They are regulated, more transparent, and carry lower counterparty risk than forwards.

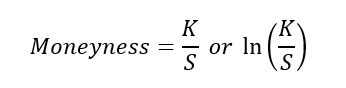

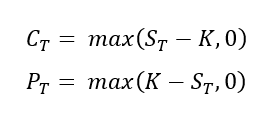

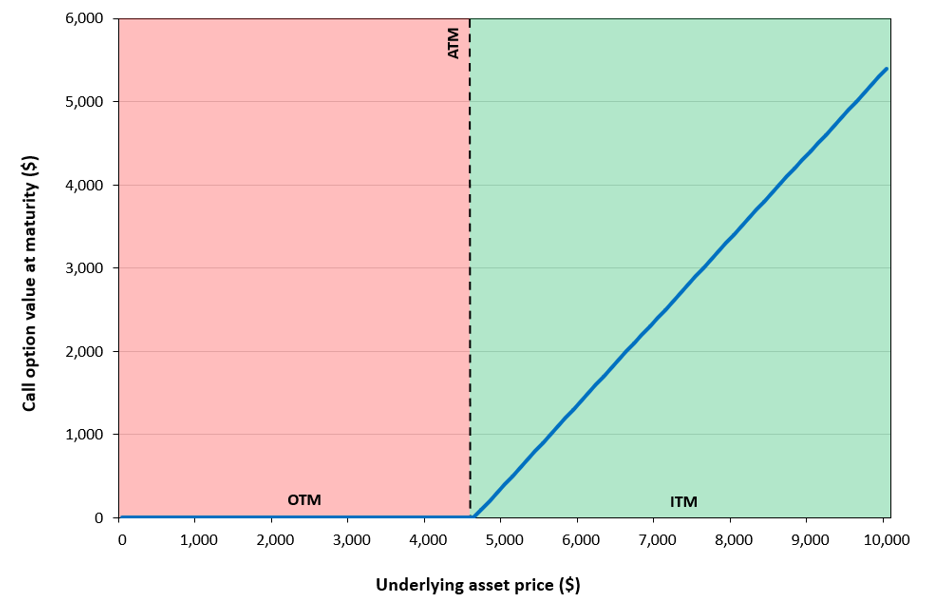

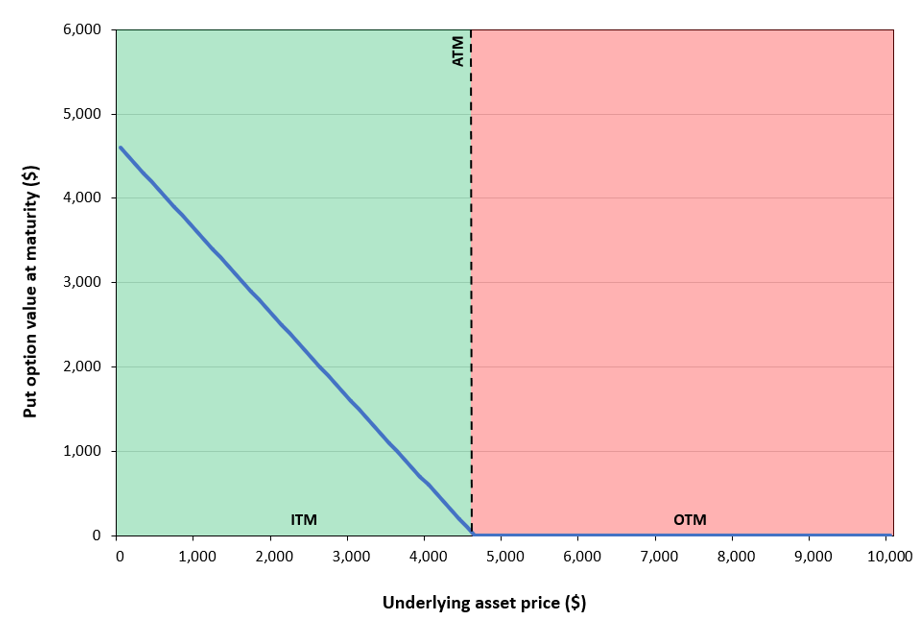

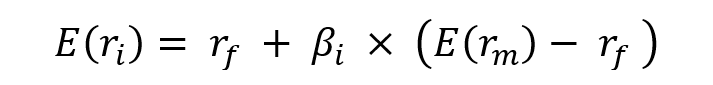

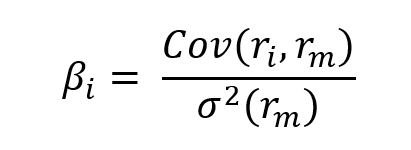

Options are contracts that give the holder the right but not the obligation to buy (call) or sell (put) an asset at a fixed strike price by a given expiration date. The buyer pays an upfront premium to the writer. If the option expires unexercised, the buyer loses only the premium. If exercised, the writer bears the payoff. Options can be American (exercise anytime) or European (exercise only at expiry) and are traded both on exchanges (standardized) and OTC (customized).

Swaps are bilateral contracts to exchange streams of cash flows over time, typically based on fixed versus floating interest rates or other reference indices. Payments are calculated on a notional principal that is not exchanged. Swaps are core OTC instruments for managing interest rate and financial risk.

Types of underlying asset classes

Underlying assets are the products on which a derivative instrument or contract derives its value. The most commonly traded underlying assets are explained below.

Equity derivatives include futures and options on stock indices, such as the S&P 500 Index. These instruments offer capital-efficient ways to manage market risk and enhance returns. Through index futures, institutional investors can achieve cost-effective hedging by locking in prices, while index options provide a non-linear, asymmetric payoff structure that protects against tail risk. Furthermore, equity swaps allow for the seamless exchange of total stock returns for floating interest rates, providing exposure to specific market segments without the capital requirements of direct physical ownership.

Interest rate derivatives include swaps and futures that help manage interest rate risk. Interest rate swaps involve exchanging fixed and floating payments, protecting banks against mismatches between loan income and deposit costs. Interest rate futures allow investors to lock in future borrowing or investment rates and provide insight into market expectations of monetary policy.

Commodity derivatives hedge price risk arising from storage, delivery, and seasonal supply-demand fluctuations. Forwards and futures on crude oil, natural gas, and power are widely used.

Foreign exchange derivatives include forward contracts and cross-currency swaps, allowing firms to hedge currency risk. Cross-currency swaps also support local currency bond markets by enabling hedging of interest and exchange rate risk.

Credit derivatives transfer the risk of default between counterparties. The most widely used is the credit default swap (CDS), which acts like insurance: the buyer pays a premium to receive compensation if a reference entity default.

Quantitative measures of derivatives market activity and size

This section presents the principal measures or statistics used to evaluate the size of the derivatives markets, covering both over-the-counter and exchange-traded instruments, the different derivatives products, and asset classes.

Notional outstanding and gross market value are the primary measures used to assess the size and economic exposure of OTC derivatives markets, while ETDs are typically evaluated using indicators such as open interest and trading volume.

Notional amount

Notional amount, or notional outstanding, is the total principal or reference value of all outstanding derivatives contracts. It captures the overall scale of positions in the derivatives market without reflecting actual market risk or cash exchanged.

For example let us consider a FX forward contract in which two parties agree to exchange $50 for euros in three months at a predetermined exchange rate. The notional amount is $50, because all cash flows (and gains or losses) from the contract are calculated with reference to this amount. No money is exchanged when the contract is initiated, and at maturity only the difference between the agreed exchange rate and the prevailing market rate determines the gain or loss computed on the $50 notional.

Now consider a call option on a stock with a strike price of $50. The notional amount is $50. The option buyer pays only an upfront premium, which is much smaller than $50, but the payoff of the option at maturity depends on how the market price of the stock compares to this $50 reference value.

When measuring notional outstanding in the derivatives market, the notional amounts of all individual contracts are simply added together. For example, one FX forward with a notional of $50 and two option contracts each with a notional of $50 result in a total notional outstanding of $150. This aggregated figure indicates the overall scale of derivatives activity, but it typically overstates actual economic risk because contracts may offset each other and only a fraction of the notional is ever exchanged.

Gross market value

Gross market value is the sum of the absolute values of all outstanding derivatives contracts with either positive or negative replacement (mark-to-market) values, evaluated at market prices prevailing on the reporting date. It reflects the potential scale of market risk and financial risk transfer, showing the economic exposure of a dealer’s derivatives positions in a way that is comparable across markets and products.

To continue the previous FX forward example, suppose a dealer has two outstanding FX forward contracts, each with a notional amount of $50. Due to movements in exchange rates, the first contract has a positive replacement value of $0.50 (the dealer would gain $0.50 if the contract were replaced at current market prices), while the second contract has a negative replacement value of –$0.40. The gross market value is calculated as the sum of the absolute values of these replacement values: |0.50| + |−0.40| = $0.90. Although the total notional outstanding of the two contracts is $100, the gross market value is only $0.90. This measure therefore reflects the dealer’s actual economic exposure to market movements at current prices, rather than the contractual size of the positions.

When this concept is extended to the entire derivatives market, the same distinction becomes apparent at a global scale. While the global derivatives market is often described as having hundreds of trillions of dollars in notional outstanding (approximately USD 850 trillion for OTC derivatives), the economically meaningful exposure is an order of magnitude smaller when measured using gross market value. Unlike notional amounts, gross market value aggregates current mark-to-market exposures, making it a more meaningful and comparable indicator of market risk and financial risk transfer across products and markets.

Open Interest

Open interest refers to the total number of outstanding derivative contracts that have not been closed, expired, or settled. It is calculated by adding the contracts from newly opened trades and subtracting those from closed trades. Open interest serves as an important indicator of market activity and liquidity, particularly in exchange-traded derivatives, as it reflects the level of active positions in the market. Measured at the end of each trading day, open interest is widely used as an indicator of market sentiment and the strength behind price trends.

For example on an exchange, a total of 100 futures contracts on crude oil are opened today. Meanwhile, 30 existing contracts are closed. The open interest at the end of the day would be: 100 (new contracts) − 30 (closed contracts) = 70 contracts. This indicates that 70 contracts remain active in the market, representing the total number of positions that traders are holding.

Trading Volume

Trading volume measures the total number of contracts traded over a specific period, such as daily, monthly, or annually. It provides insight into market liquidity and activity, reflecting how actively derivatives contracts are bought and sold. For OTC markets, trading volume is often estimated through surveys, while for exchange-traded derivatives, it is directly reported.

Consider the same crude oil futures market. If during a single trading day, 50 contracts are bought and 50 contracts are sold (including both new and existing positions), the trading volume for the day would be: 50 + 50 = 100 contracts

Here, trading volume shows how active the market is on that day (flow), while open interest shows how many contracts remain open at the end of the day (stock). High trading volume with low open interest may indicate rapid turnover, whereas high open interest with rising prices can signal strong bullish sentiment.

Key sources of statistics on global derivatives markets

Bank for International Settlements (BIS)

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) provides quarterly statistics on exchange-traded derivatives (open interest and turnover in contracts, and notional amounts) and semiannual data on OTC derivatives outstanding (notional amounts and gross market values across risk categories like interest rates, FX, equity, commodities, and credit). All the data used in this post has been sourced from the BIS database.

Data are collected from over 80 exchanges for ETDs and via surveys of major dealers in 12 financial centers for OTC derivatives. BIS ensures comparability by standardizing definitions, consolidating country-level data, halving inter-dealer positions to avoid double counting, and converting figures into USD. Interpolations are used to fill gaps between triennial surveys, ensuring consistent time series for analysis.

International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA)

ISDA develops and maintains standardized reference data and contractual frameworks that underpin global OTC derivatives markets. This includes machine-readable definitions and value lists for core market terms such as benchmark rates, floating rate options, currencies, business centers, and calendars, primarily derived from ISDA documentation (notably the ISDA Interest Rate Derivatives Definitions). The data are distributed via the ISDA Library and increasingly designed for automated, straight-through processing.

ISDA’s standards are created and updated through industry working groups and are widely used to support trade documentation, confirmation, clearing, and regulatory reporting. Initiatives such as the Common Domain Model (CDM) and Digital Regulatory Reporting (DRR) translate market conventions and regulatory requirements across multiple jurisdictions into consistent, machine-executable logic. While ISDA does not publish comprehensive market volume statistics, its frameworks play a central role in harmonizing OTC derivatives markets and enabling reliable post-trade transparency.

Futures Industry Association (FIA)

Futures Industry Association (FIA), via FIA Tech, provides comprehensive derivatives data including position limits, exchange fees, contract specifications, and trading volumes for futures/options across global products.

Sources aggregate from exchanges, indices (1,800+ products, 100,000+ constituents), and regulators for reference data like symbologist and corporate actions. The process involves standardizing data into consolidated formats with 500+ attributes, automating regulatory reporting (e.g., CFTC ownership/control), and ensuring compliance via databanks.

How to get the data

The data discussed in this article is drawn from the BIS, FIA and Visual Capitalist. For comprehensive statistics on global derivatives markets (both over-the-counter (OTC) and exchange-traded derivatives (ETDs)), the data are available at https://data.bis.org/ and for exchange-traded derivatives specifically, detailed data are provided by the Futures Industry Association (FIA) through its ETD volume reports, accessible at https://www.fia.org/etd-volume-reports. Data on equity spot market and real economy sectors are sourced from Visual Capitalist.

Derivatives market business statistics

Global derivatives market

In this section, we focus on two core measures of derivatives market activity and size: the notional amount outstanding and the gross market value, which together provide complementary perspectives on the scale of contracts and the associated economic exposure.

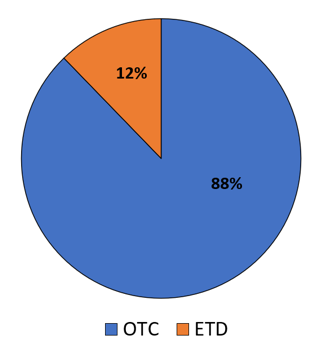

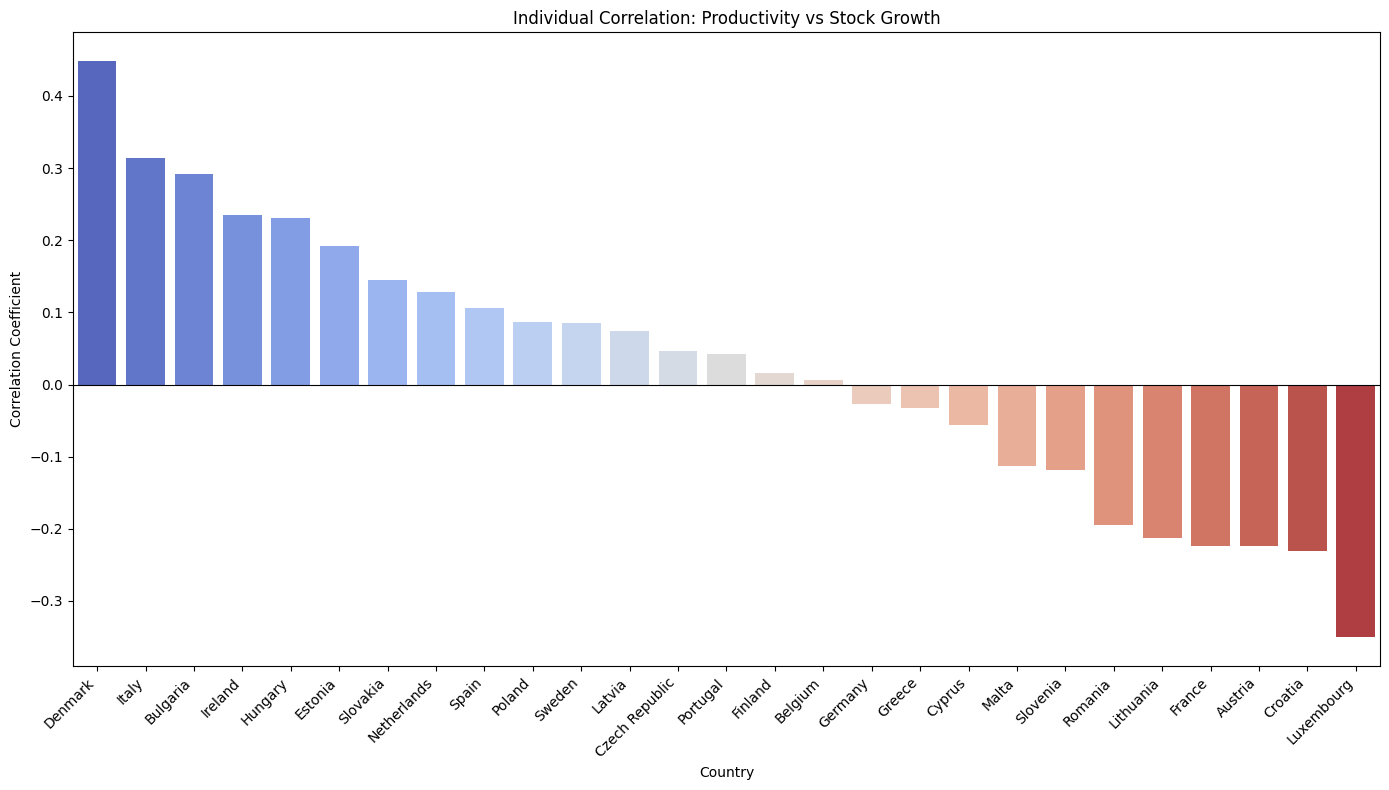

As of 30th July 2025, the global derivatives market is estimated to have an outstanding notional value of approximately USD 964 trillion, according to the Bank for International Settlements (BIS). As illustrated in the figure below, the market is largely dominated by over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives, which account for nearly 88% of total notional amounts, whereas exchange-traded derivatives (ETDs) represent a comparatively smaller share of about USD 118 trillion.

Figure 1. Derivatives Markets: OTC versus ETD (2025)

Source: computation by the author (BIS data of 2025).

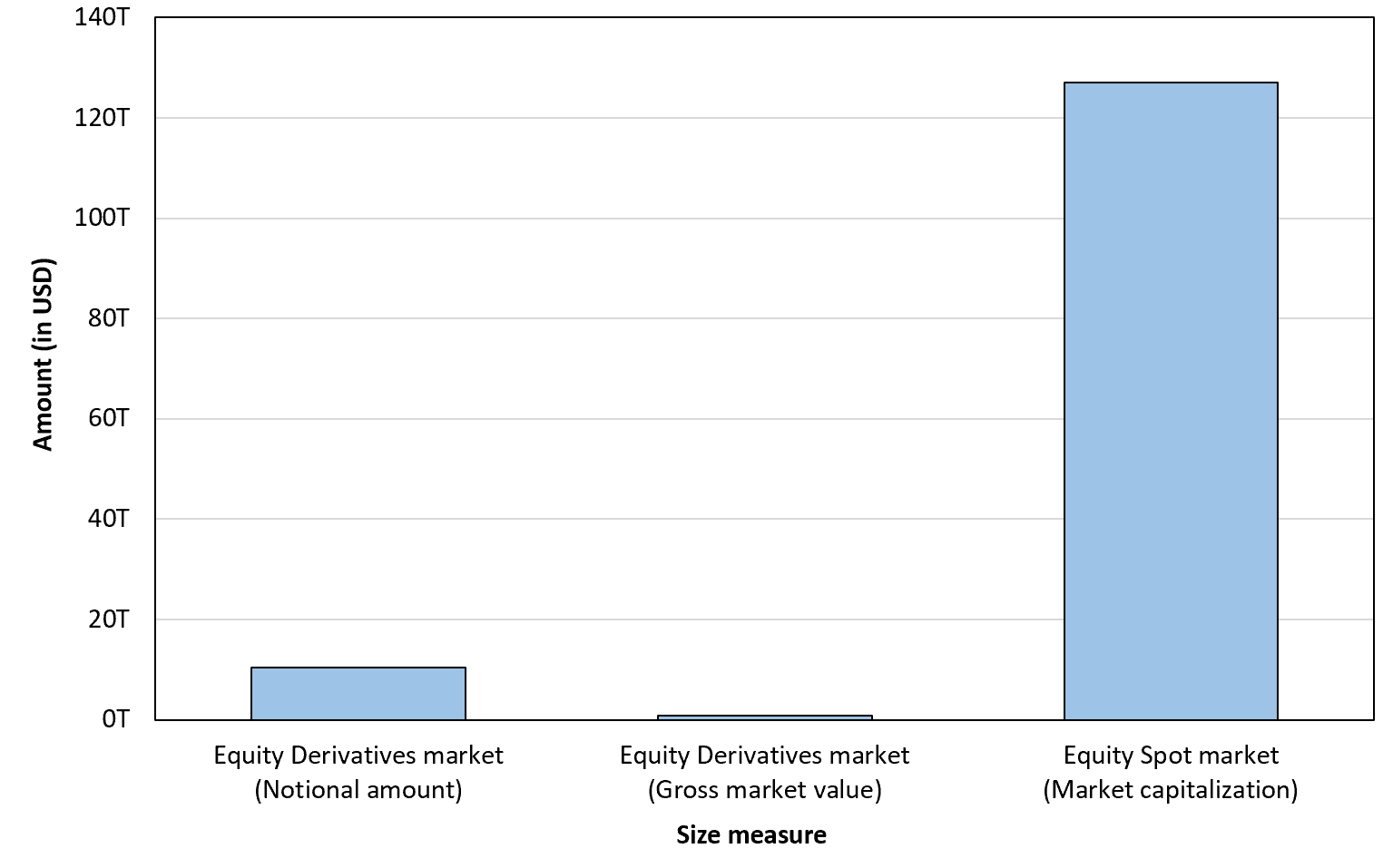

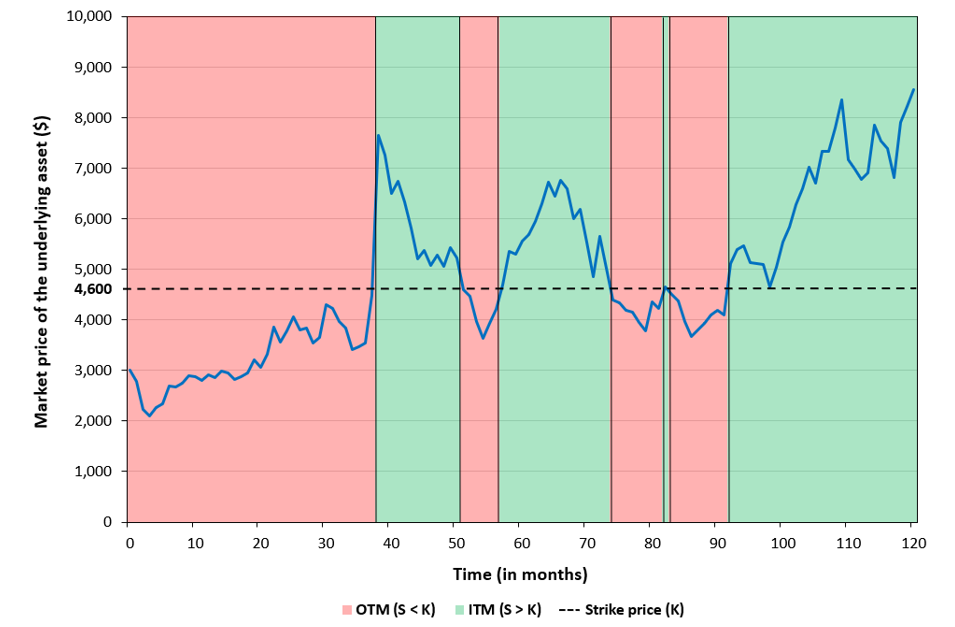

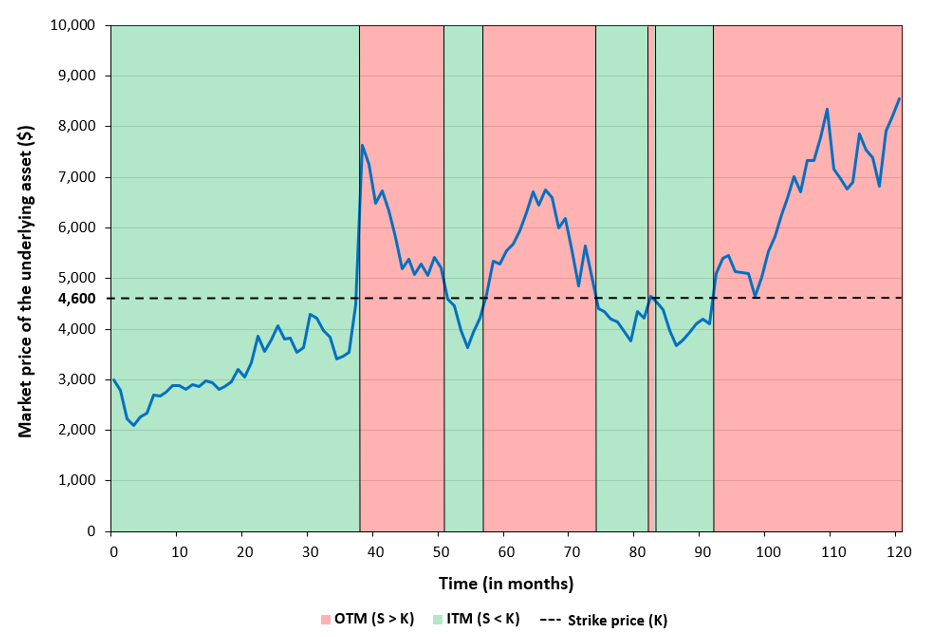

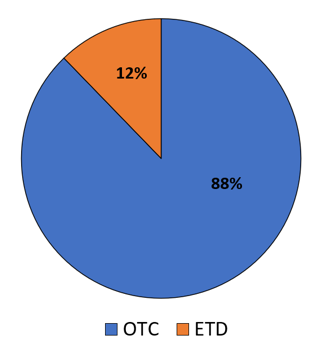

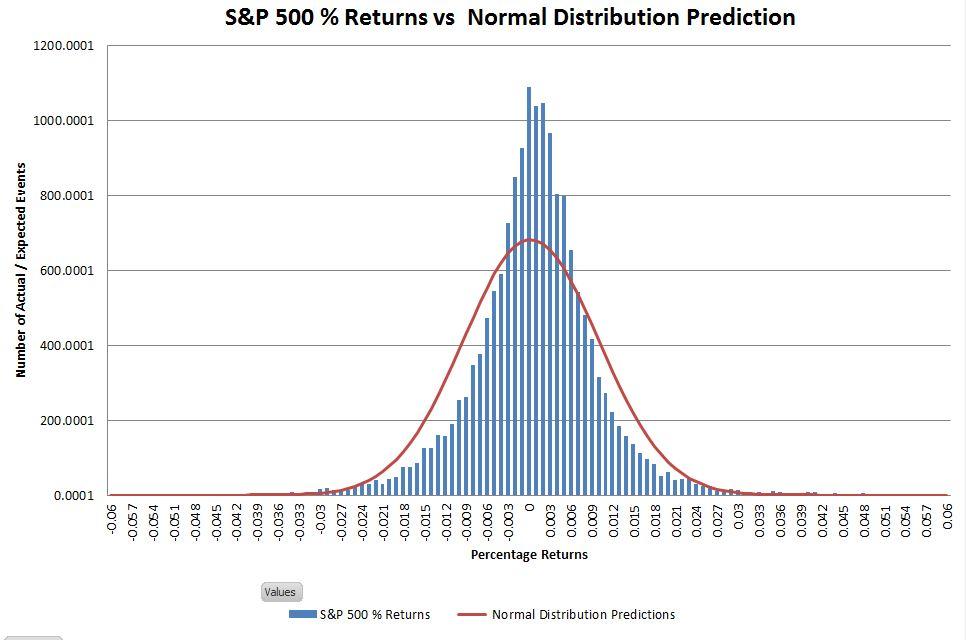

Figure 2 below compares the scale of the global equity derivatives market with that of the underlying equity spot market as of mid-2025. The figure shows that, although equity derivatives represent a sizeable market in notional terms, they are still much smaller than the equity spot market measured by market capitalization. This suggests that the primary locus of economic value in equities remains in the spot market, while the derivatives market mainly represents contingent claims written on that underlying value rather than a comparable pool of market wealth. The relatively small gross market value of equity derivatives further indicates that only a limited portion of derivative notional translates into actual market exposure.

Figure 2. Equity Markets: Spot versus Derivatives (2025)

Source: computation by the author (BIS and Visual Capitalist data of 2025).

Data sources: global derivatives notional outstanding as of mid-2025 BIS OTC and exchange traded data; global equity spot market capitalization as of 2025 (Visual Capitalist).

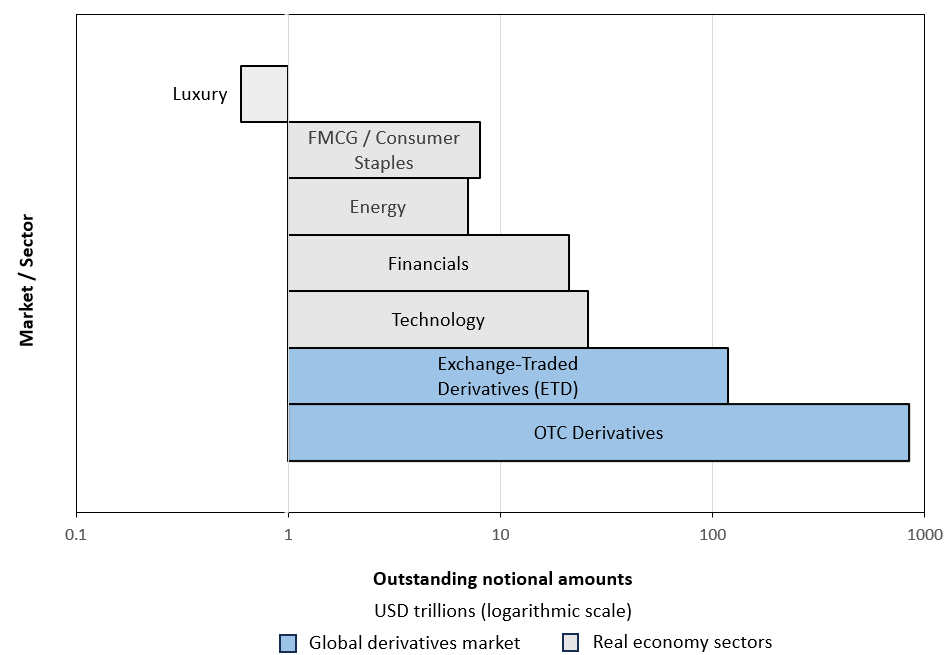

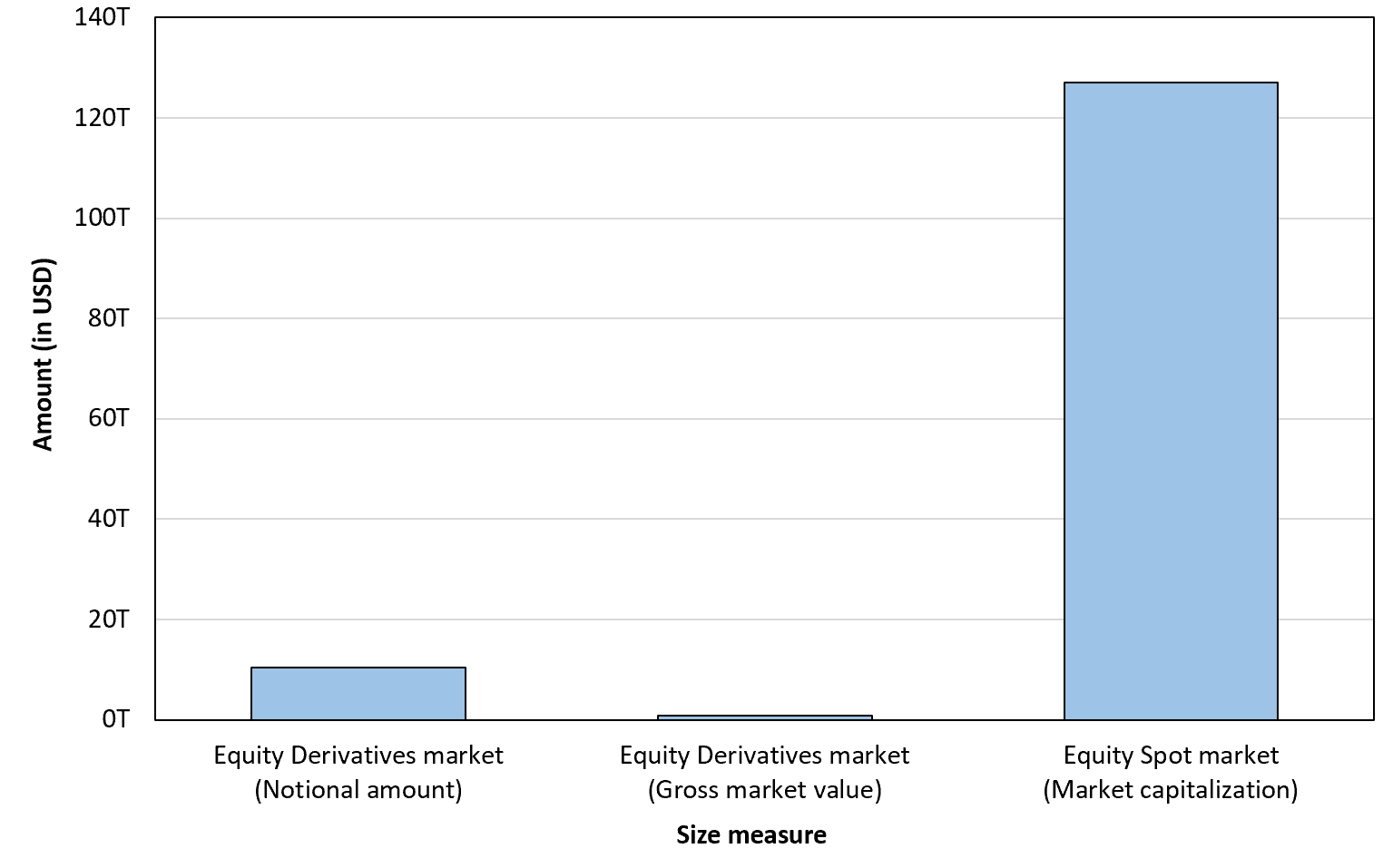

Figure 3 below juxtaposes the global derivatives market with selected real-economy sectors to provide an intuitive comparison of scale. Values are reported in USD trillions and plotted on a logarithmic axis, such that equal distances along the horizontal scale correspond to ten-fold (×10) changes in magnitude rather than linear increments. This representation allows quantities that differ by several orders of magnitude to be meaningfully displayed within a single chart.

Interpreted in this manner, the figure illustrates that the notional size of derivatives markets far exceeds the market capitalization of major real-economy sectors, including technology, financials, energy, fast moving consumer goods (FMCG), and luxury. The comparison is illustrative rather than like-for-like, and is intended to contextualize the scale of financial contract exposure rather than to imply equivalent economic value or direct risk.

Figure 3. Scale of Global Derivatives Relative to Major Real-Economy Sectors (2025)

Source: computation by the author (BIS and Visual Capitalist data).

Data sources: BIS OTC derivatives statistics (June 2025) for notional outstanding; Visual Capitalist global stock market sector data (2025) for sector market capitalizations; companies market cap / Visual Capitalist for luxury company market caps.

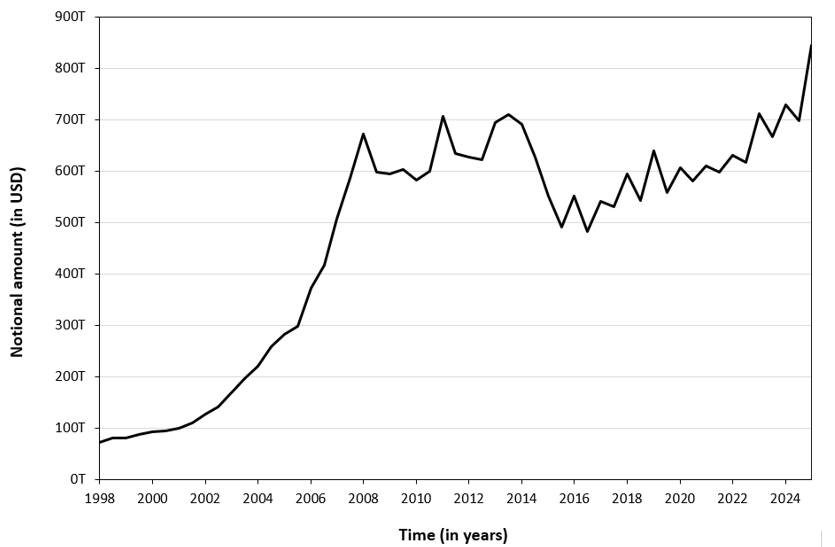

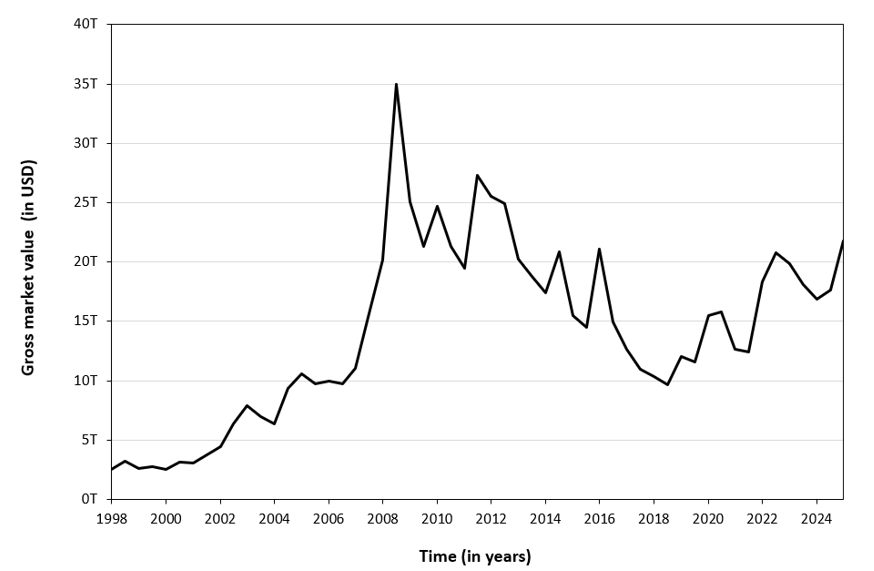

OTC derivatives market

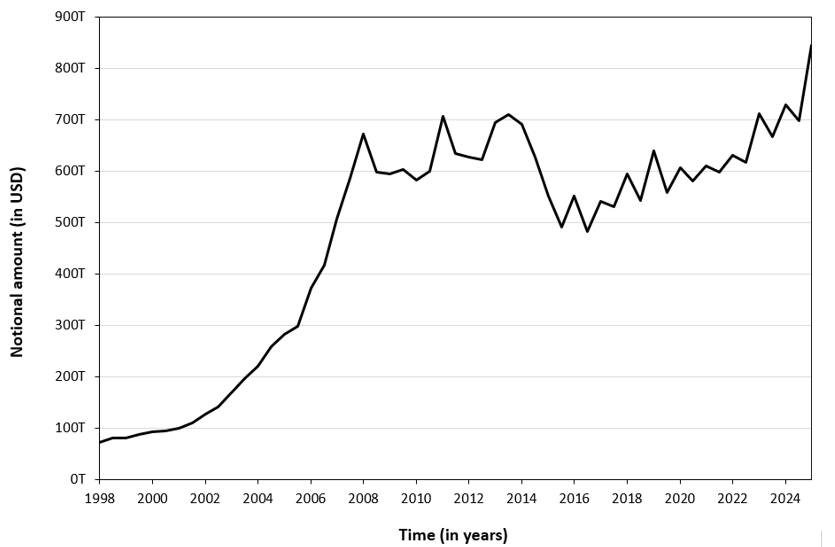

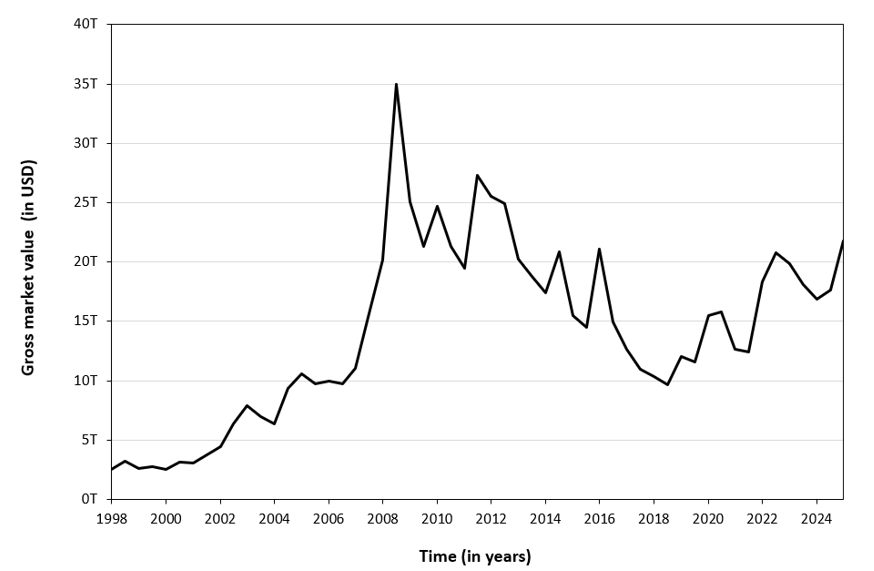

Figures 4 and 5 below illustrate the evolution of the OTC derivatives market from 1998 to 2025 using the two measures discussed above: outstanding notional amounts (Figure 4) and gross market value (Figure 5). As the data show, notional outstanding tends to overstate the effective economic size of the market, as it reflects contractual face values rather than actual risk exposure. By contrast, gross market value provides a more economically meaningful measure by capturing the current cost of replacing outstanding contracts at prevailing market prices.

Figure 4. Size of the OTC Derivatives Market (Notional amount)

Source: computation by the author (BIS data).

Figure 5. Size of the OTC Derivatives Market (Gross market value)

Source: computation by the author (BIS data).

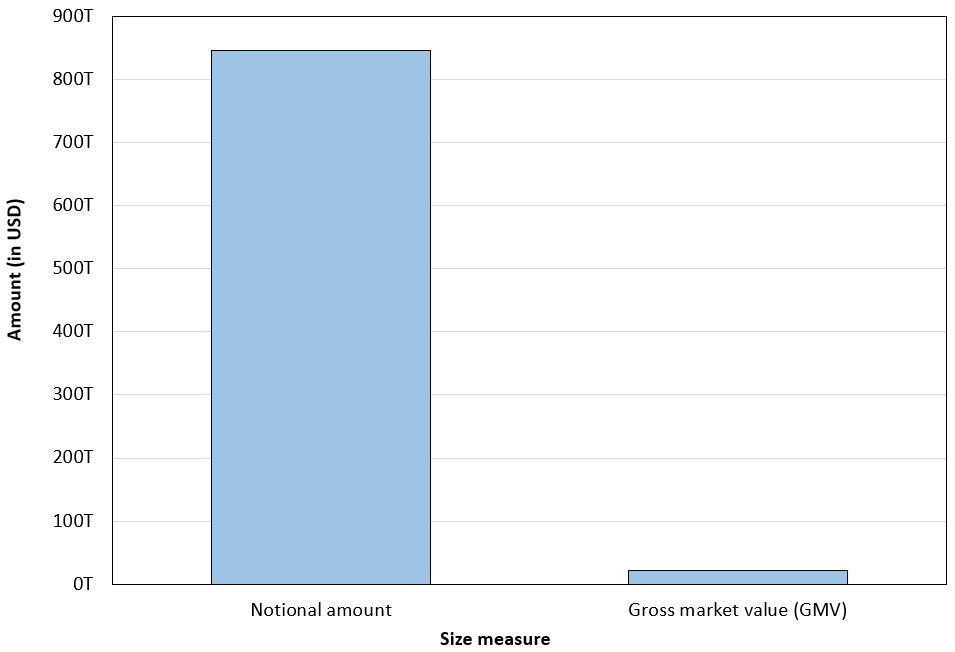

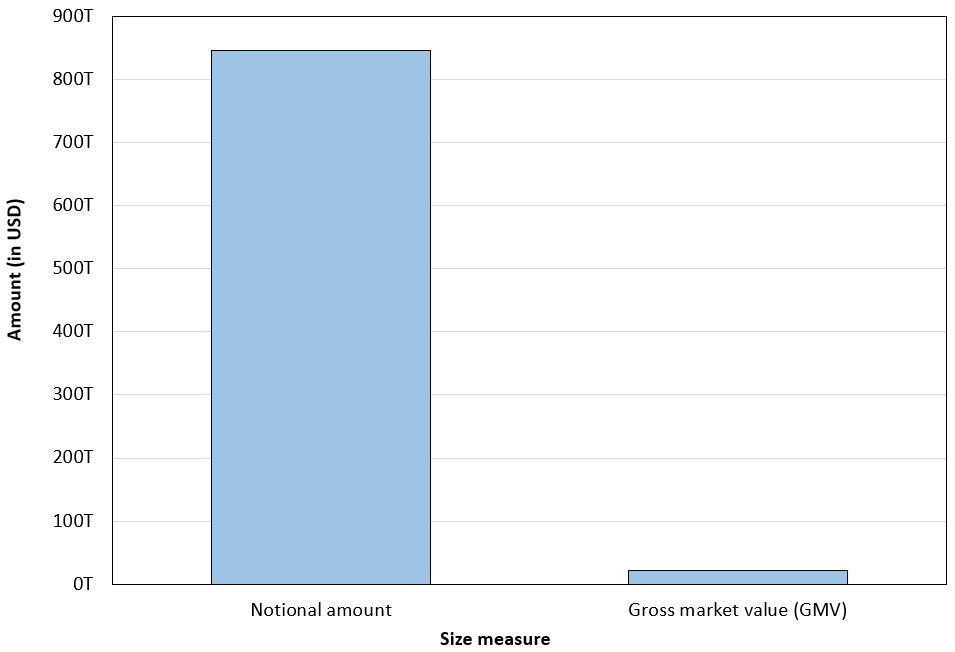

The figure below illustrates the OTC derivatives market data as of 30th July 2025 based on the two metrics discussed above: outstanding notional amounts and gross market value. As the data show, Gross market value (GMV) represents only about 2.6% of total notional outstanding, highlighting the large gap between contractual face values and economically meaningful exposure.

Figure 6. Size measure of the OTC derivatives market (2025)

Source: computation by the author (BIS data).

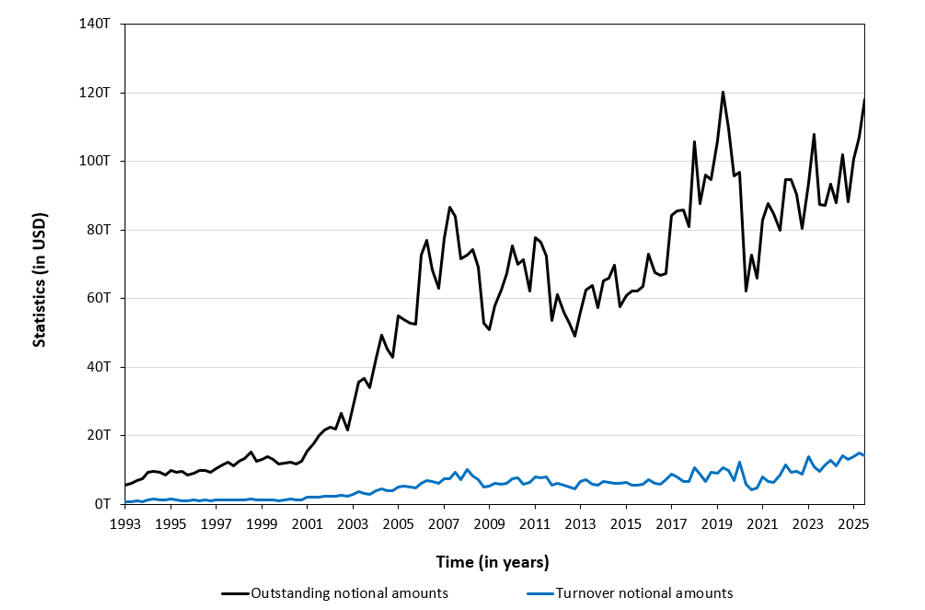

Exchange-traded derivatives market

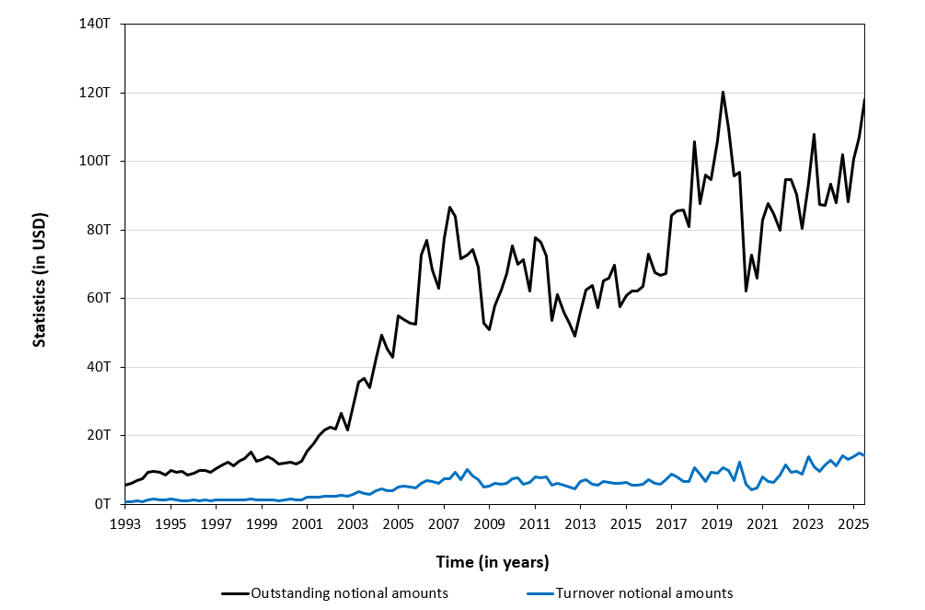

Figure 7 below illustrates the growth of the exchange-traded derivatives market from 1993 to 2025, based on outstanding notional amounts (open interest) and turnover notional amounts (trading volume). For comparability across contracts and exchanges, open interest is expressed in notional terms by multiplying the number of open contracts by their contract size, yielding US dollar equivalents. Turnover is defined as the notional value of all futures and options traded during the period, with each trade counted once.

Figure 7. Size of the Exchange-Traded Derivatives Market

Source: computation by the author (BIS data).

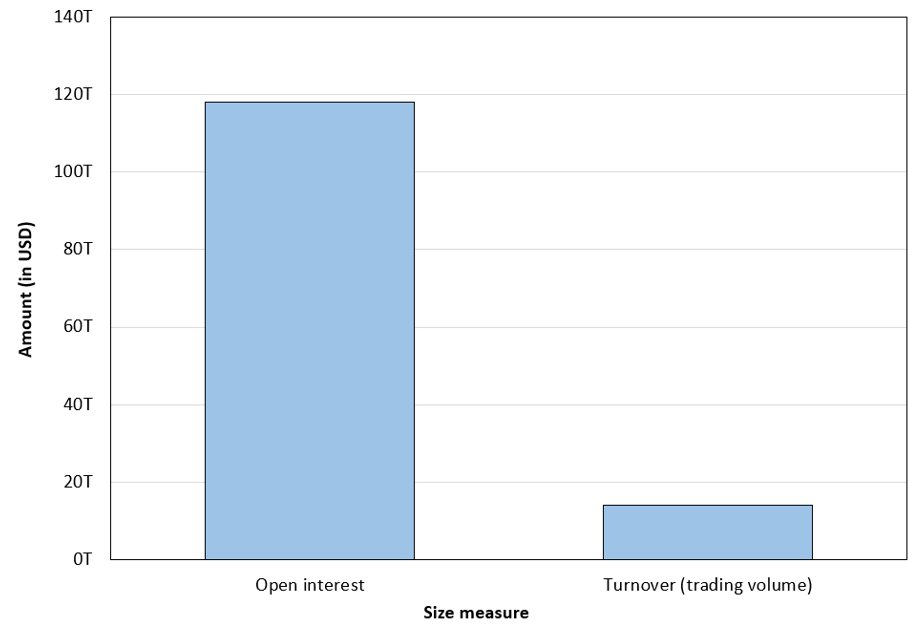

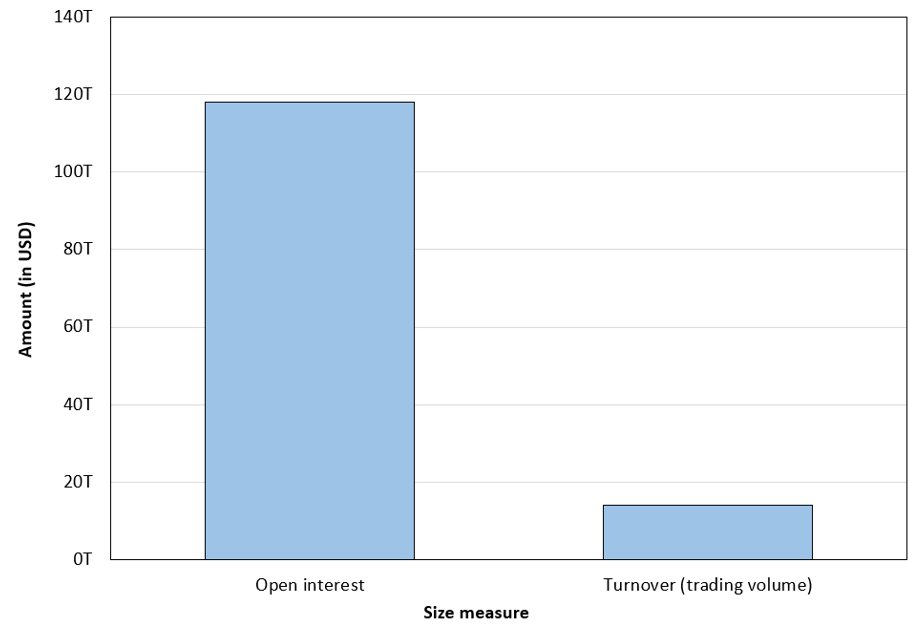

The figure below illustrates the exchange-traded derivatives market data as of 30th July 2025 based on the two metrics discussed above: open interest and turnover (trading volume). The chart shows that only about 12%, of the open positions is actively traded, highlighting the difference between market size and the trading activity.

Figure 8. Size of the Exchange traded derivatives market (2025)

Source: computation by the author (BIS data).

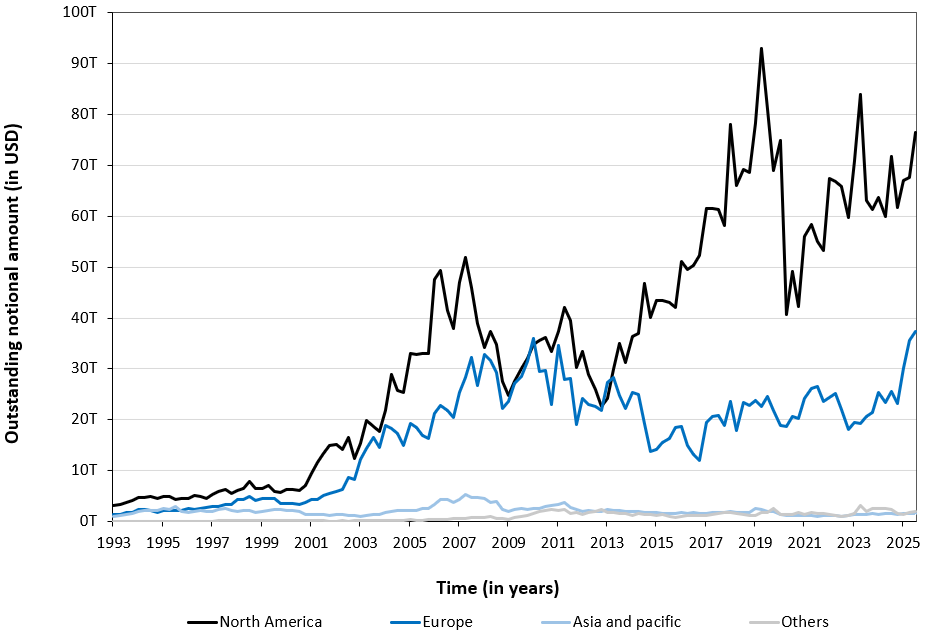

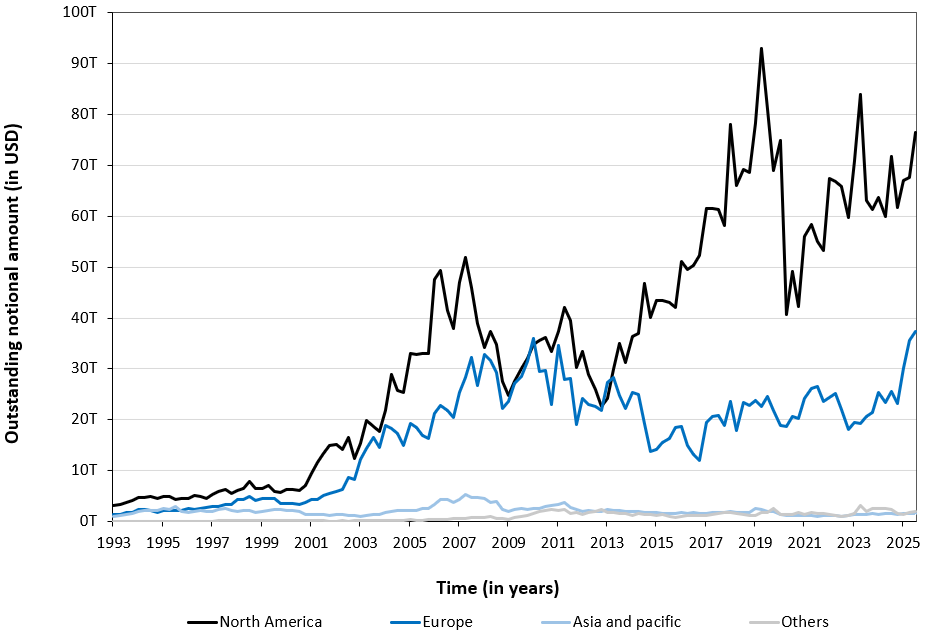

Figure 9 below illustrates the evolution of the global exchange-traded derivatives market from 1993 to 2025, measured by outstanding notional amounts across major regions. The figure reveals a pronounced concentration of activity in North America and Europe, which drives most of the market’s expansion over time, while Asia-Pacific and other regions play a more modest role. Despite cyclical fluctuations, the overall trajectory is one of sustained long-run growth, underscoring the increasing importance of exchange-traded derivatives in global risk management and price discovery.

Figure 9. Size of the Exchange-Traded Derivatives Market by geographical locations

Source: computation by the author (BIS data).

Underlying asset classes

This section analyzes underlying asset-class statistics for derivatives traded in exchange-traded (ETD) and over-the-counter (OTC) markets.

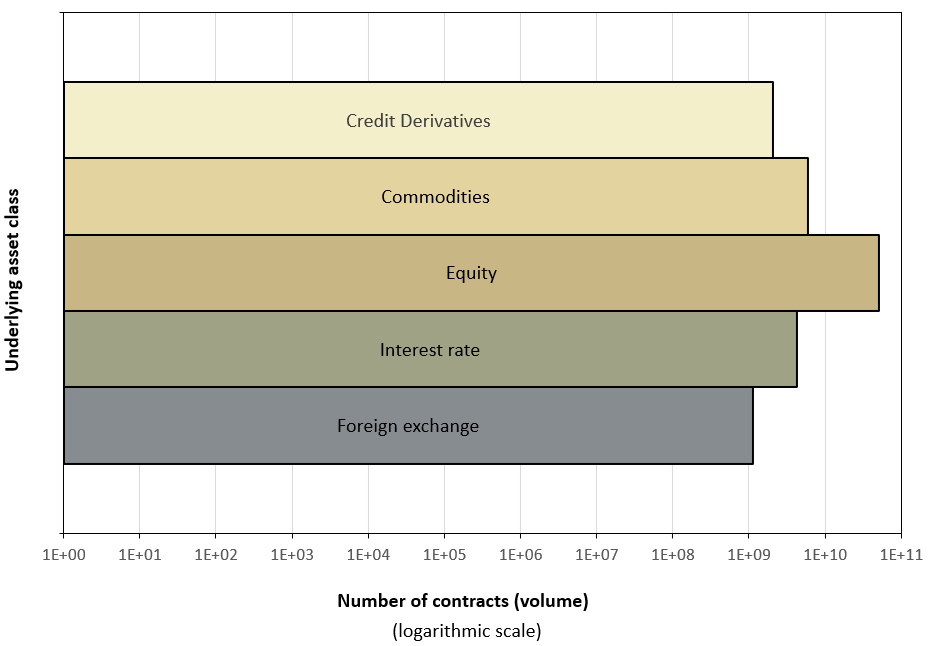

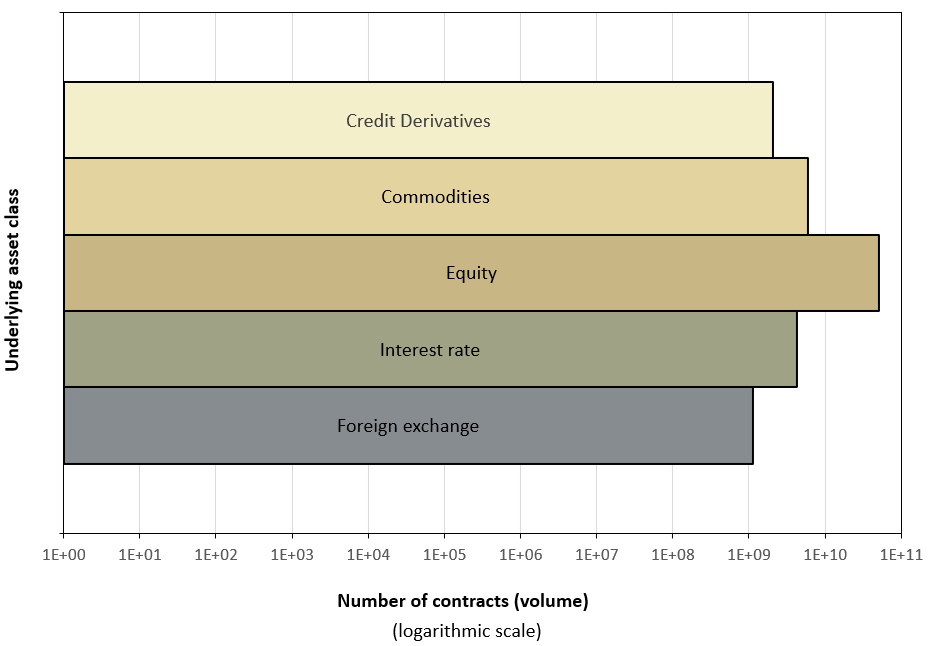

Figure 10 below presents the distribution of exchange-traded derivatives (ETDs) activity across major underlying asset classes. When measured by the number of contracts traded (volume), the market is highly concentrated, with Equity derivatives dominating and accounting for the vast majority of activity. This is followed at a significant distance by Interest Rate and Commodity derivatives. However, this distribution reverses when measured by the notional value of outstanding contracts, where Interest Rate derivatives represent the largest share of the market due to the high underlying value of each contract.

Figure 10. Size of the exchange-traded derivatives market by asset classes

Source: computation by the author (FIA data).

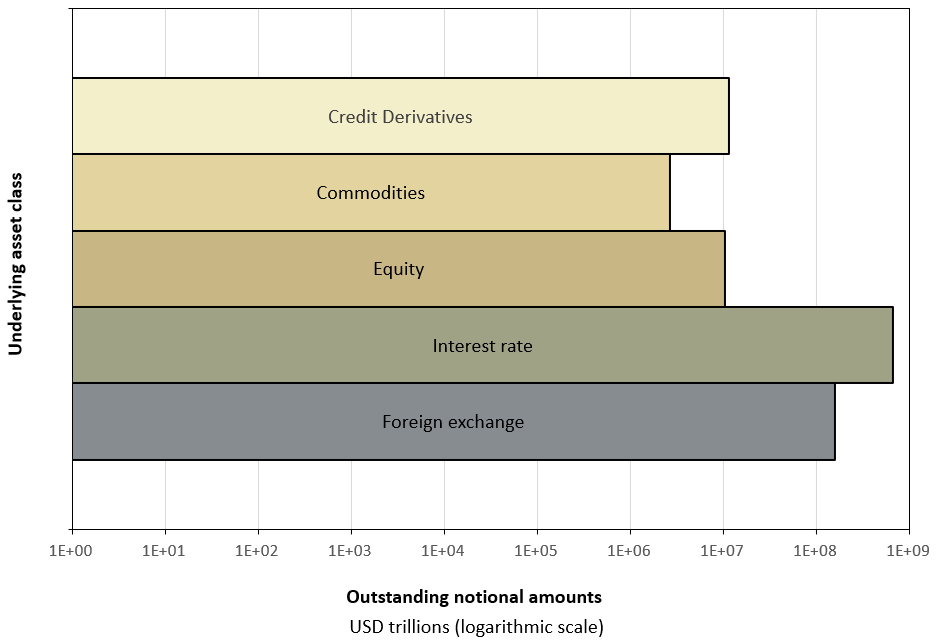

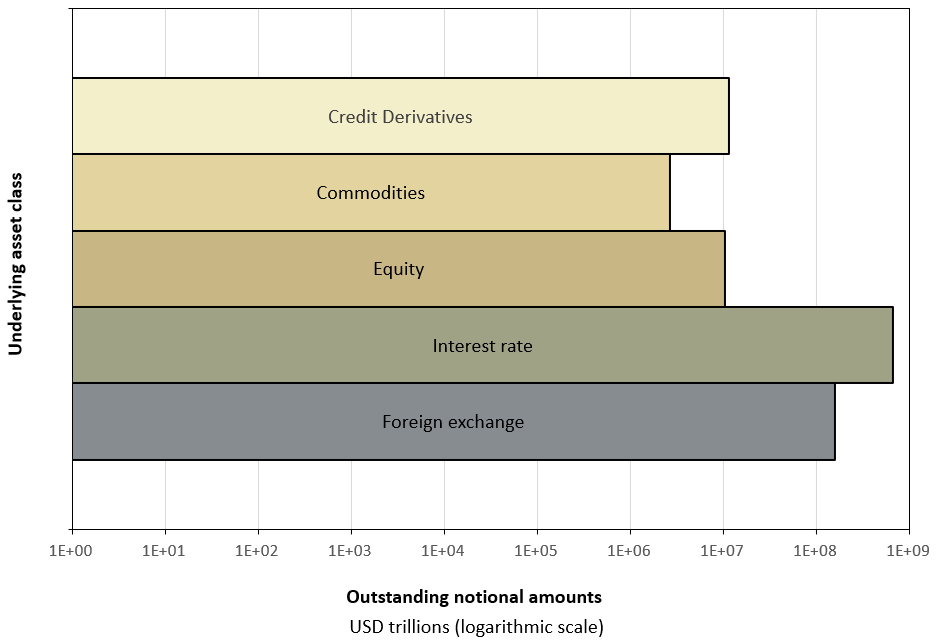

Figure 11 below presents the distribution of OTC derivatives activity across major underlying asset classes, measured by the outstanding notional amounts and displayed on a logarithmic scale. Read in this way, the chart shows that OTC activity is broadly diversified across interest rates, equity indices, commodities, foreign exchange, and credit, with interest rate and foreign exchange derivatives accounting for the largest contract volumes.

Figure 11. Size of the OTC derivatives market by asset classes

Source: computation by the author (BIS data).

Role of the Black–Scholes–Merton (BSM) model

The Black–Scholes–Merton (BSM) model played a role in financial markets that extended well beyond option pricing. As argued by MacKenzie and Millo (2003), once adopted by traders and exchanges, it actively shaped how options markets were organized, priced, and operated rather than merely describing pre-existing price behaviour. Its use at the Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE) helped standardize quoting practices, enabled model-based hedging, and supported the rapid growth of liquidity in listed options markets.

At a broader level, MacKenzie (2006) shows that BSM contributed to a transformation in financial culture by embedding theoretical assumptions about risk, volatility, and rational pricing into everyday market practice. In this sense, BSM acted as an “engine” that reshaped markets and economic behaviour, not simply a “camera” recording them.

Beyond markets and firms, the diffusion of the BSM model also had wider societal implications. By formalizing risk as something that could be quantified, priced, and hedged, BSM contributed to a broader cultural shift in how uncertainty was perceived and managed in modern economies (MacKenzie, 2006). This reframing reinforced the view that complex economic risks could be controlled through mathematical models, with public perceptions of financial stability.

Why should you be interested in this post?

For anyone aiming for a career in finance, understanding the derivatives market is essential, as it is currently one of the most actively traded markets and is expected to grow further. Studying the statistics and business impact of derivatives provides valuable context on past challenges and the solutions developed to manage risks, offering a solid foundation for analyzing and navigating modern financial markets.

Related posts on the SimTrade blog

▶ Jayati WALIA Derivatives Market

▶ Alexandre VERLET Understanding financial derivatives: options

▶ Alexandre VERLET Understanding financial derivatives: forwards

▶ Alexandre VERLET Understanding financial derivatives: futures

▶ Akshit GUPTA Understanding financial derivatives: swaps

▶ Akshit GUPTA The Black Scholes Merton model

▶ Luis RAMIREZ Understanding Options and Options Trading Strategies

Useful resources

Academic research on option pricing

Black F. and M. Scholes (1973) The pricing of options and corporate liabilities. Journal of Political Economy, 81(3), 637–654.

Merton R.C. (1973) Theory of rational option pricing. The Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science, 4(1), 141–183.

Hull J.C. (2022) Options, Futures, and Other Derivatives, 11th Global Edition, Chapter 15 – The Black–Scholes–Merton model, 338–365.

Academic research on the role of models

MacKenzie, D., & Millo, Y. (2003). Constructing a Market, Performing Theory: The Historical Sociology of a Financial Derivatives Exchange. American Journal of Sociology, 109(1), 107–145.

MacKenzie, D. (2006). An Engine, not a Camera: How Financial Models Shape Markets. MIT Press.

Data

Bank for International Settlements (BIS). Retrieved from BIS Statistics Explorer.

Futures Industry Association (FIA). Retrieved from ETD Volume Reports.

Visual Capitalist. Retrieved from The Global Stock Market by Sector.

Visual Capitalist. Retrieved from Piecing Together the $127 Trillion Global Stock Market.

About the author

The article was written in February 2026 by Saral BINDAL (Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur, Metallurgical and Materials Engineering, 2024-2028 & Research assistant at ESSEC Business School).

▶ Discover all articles written by Saral BINDAL

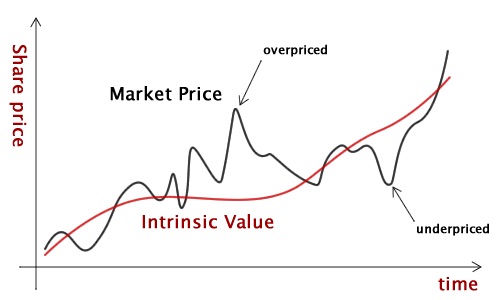

Source: Fisher Investments

Source: Fisher Investments

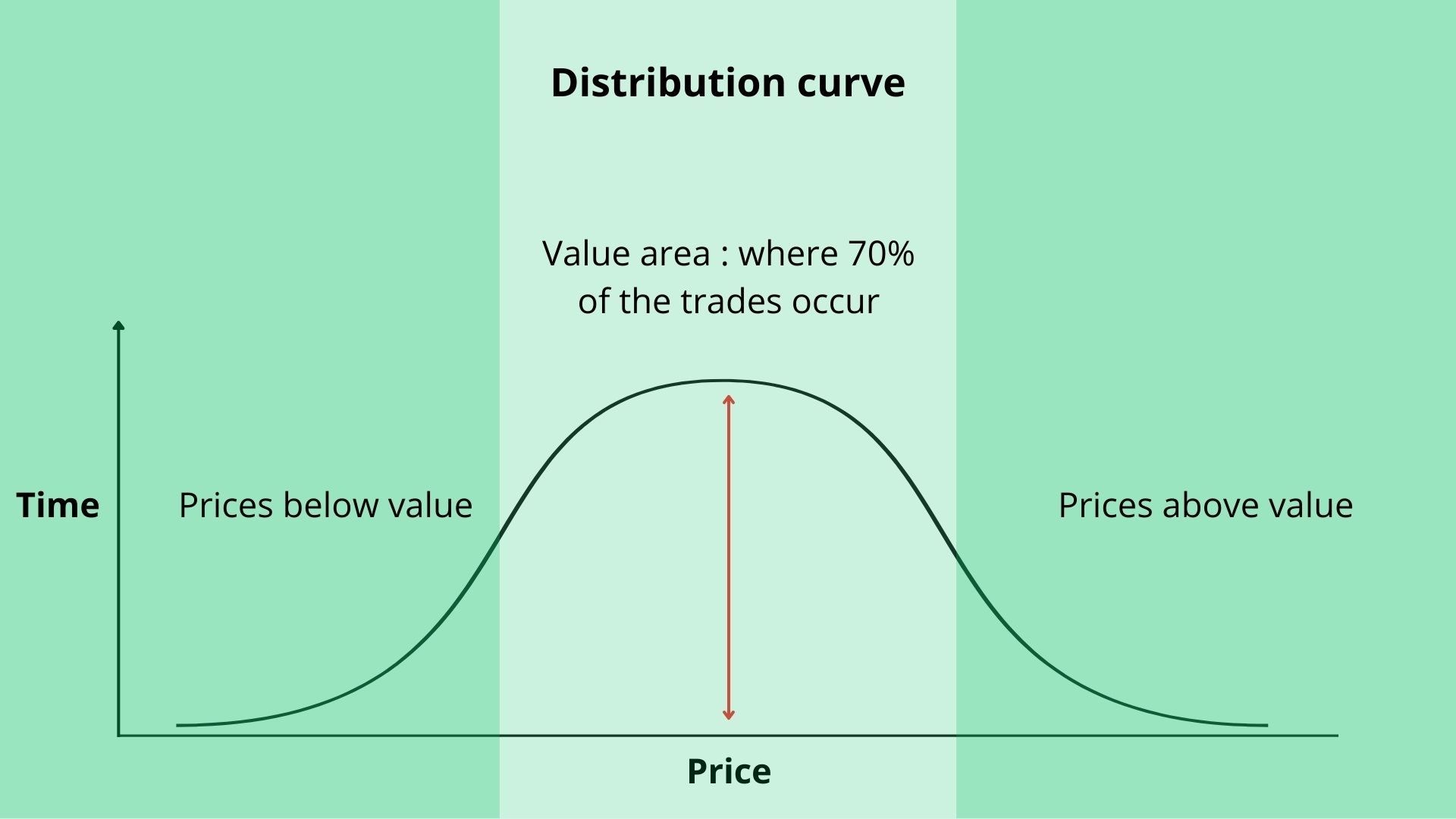

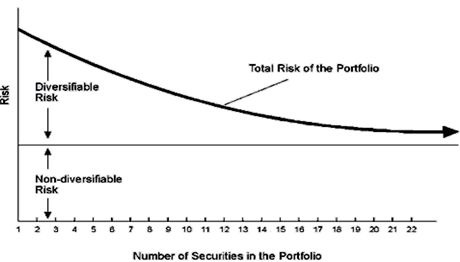

Increasing the number of securities in a portfolio reduces unnecessary risk, limiting the risk of excessive fear for the investor

Increasing the number of securities in a portfolio reduces unnecessary risk, limiting the risk of excessive fear for the investor