Could the 2008 financial crisis been foreseen?

In September 2008, the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers broke the news and disclosed to the public what would become the biggest financial crisis since 1929. This crisis, fuelled by the speculation around ill-rated and poorly packaged mortgage securities, has been explained by some by the “black swan” theory.

Developed by Nassim Nicholas Taleb (2007), the black swan theory states that, similarly to black swans which were unthinkable for Europeans before they conquered Australia, exceptional financial events have a very low probability of occurring and are unpredictable from a statistics point of view. Nonetheless, is it fair to consider the 2008 as an unpredictable “black swan”?

According to the dominant economic theory, 2008 was a surprise

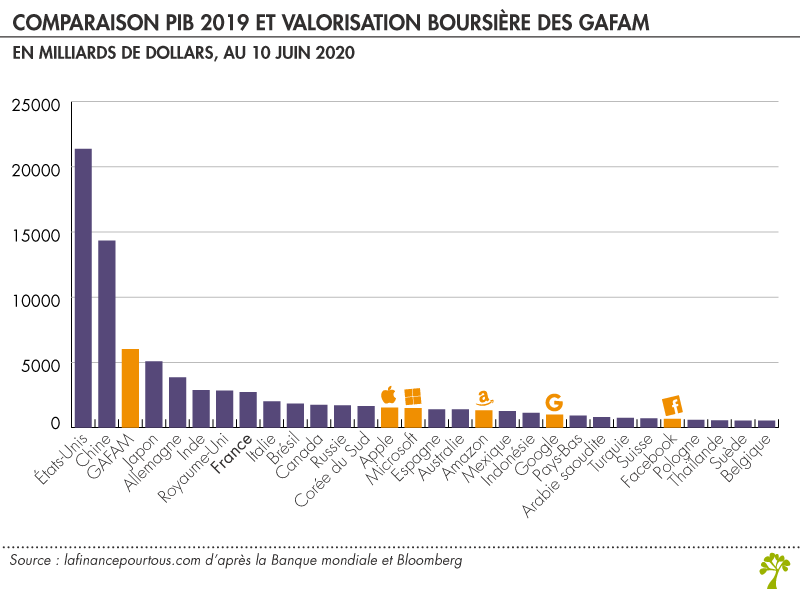

From the 1980’ to 2007, the “great moderation” period has reinforced in the dominant economic school of thought (the new classical economy) the idea of a stable long-term growth, uninterrupted by economics shocks and crisis. Indeed, from the 1980’, especially in the United States, all the indicators are green. The GDP is growing steadily, unemployment is low (under 4% for three years in a row under the Clinton presidency) and credit is accessible.

The “great moderation” is characterized by the reduction in the volatility of business cycle fluctuations in developed nations compared with the decades before. The flattening of business cycle fluctuations had been on the public debate since the 1967 and the famous conference led by Social Science Research Council Committee On Economic Stability called “Is the business cycle obsolete”.

During this period, Central banks became more independent, and governments began to widely use counter-cyclical policies in order to maintain growth in the long term with a balanced budget.

In “La Grande Crise: comment en sortir autrement”, James K. Galbraith describes this thirty-year period as a “great mirage”: everything was going well, so economists believed that everything was going well in the economy, and that everything would go well in the economy. Ben Bernanke, Governor of the Federal Reserve between 2005 and 2014, explained in 2015 that between the 1980’ and 2007, developed economics had returned to a stable economic pattern, thus that a shock could inevitably come from outside the economy. This framework of thought shared by most economists, politicians and central bankers at that time can explain why the 2008 crisis was not even foreseeable, as it is impossible to foresee an external shock.

Nonetheless, the analysis of certain parameters foreshadowed an upcoming financial crisis

During the early 2000s, Dean Baker studied the evolution of bubbles across history in order to understand when the future crisis would occur. He specifically studied the price-to-earnings ratio (stock price / net income) of stocks on the stock market. He explained that a bubble appears when the gap between price and earnings widens in a non-proportional way (i.e., the stock prices increase more quickly than the net income or earnings does). During the course of his analysis, Dean Baker has even estimated the size of the mortgage bubble. He valued the bubble at $8,000 billion, which is strangely equivalent to the total amount of wealth destroyed during the 2008 financial crisis…

Minsky in 1986 stated that financial crises are a moment of the financial cycle. He explained that during a period of stability (here the “great moderation”), speculators get bored and begin to take more and more risks, until they reach a Ponzi phase, and the economy collapses. According to Minsky, the international wave of financial deregulation and the recombination of investment and commercial banks during the 1980s have allowed the speculative game to become even more dangerous. According to this theory, the 2008 crisis was thus bound to happen, the only uncertainty has been the exact date of the collapse of the economy.

Financial crisis are not black swans: they are rather common

Modern history is paved with financial crises. In 1637 the “tulip mania” in Holland led to a dramatic increase and then collapse in the price of the tulip bulb. At the height of the tulip craze, in February 1637, promises to sell a bulb were negotiated for ten times the annual salary of a skilled craftsman. Some historians have called this crisis the “first speculative bubble” in history, as the sudden drop in prices is similar to a crash and the financial instruments used (futures sales, “options” contracts – purchase/sale at a fixed price in advance) make it a real financial crisis.

Anonymous, The Sale of Tulip Onions, 17th century. Oil on wood

During the XIXth century, the crises of the modern era appear. They are usually overproduction industrial crises which spread internationally. In 1857 occurred the “1st international crisis of the industrial era”. A series of bank failures in the US spread to the financial spheres in Europe, and then to the real economy, impacting industrial production and generating wage decreases. In May 1873, an intense speculation around real-estate led to a financial crash which spread to the rest of developed world. It was followed by a depression, a thirty-year period of depression and growth deceleration, characterized by persistent underemployment.

The 20th century also had its share of financial crises: 1929, the 1970s, etc.

Furthermore, economic research on financial crisis mainly focuses a western-centric event. If developed countries have enjoyed a high degree of stability, despite regular financial crises, it is not the case for economies of less-developed countries, which experience numerous repeated financial crises.

Useful resources

Baker D. (2008), The housing bubble and the financial crisis, Center for Economic and Policy Research (issue #46)

Bernanke B. (2015) The Federal Reserve and the Financial Crisis.

Galbraith J. (2015) La Grande Crise : Comment en Sortir Autrement.

Taleb N. (2007) The Black Swan: The Power of the Unpredictable.

About the author

Article written in June 2021 by Raphaël ROERO DE CORTANZE (ESSEC Business School, Master in Management, 2019-2022).