In this article, Yann TANGUY (ESSEC Business School, Global Bachelor in Business Administration (GBBA), 2023-2027) explains the concept of “diworsification” and shows how to avoid falling into its trap.

The Concept of Diworsification

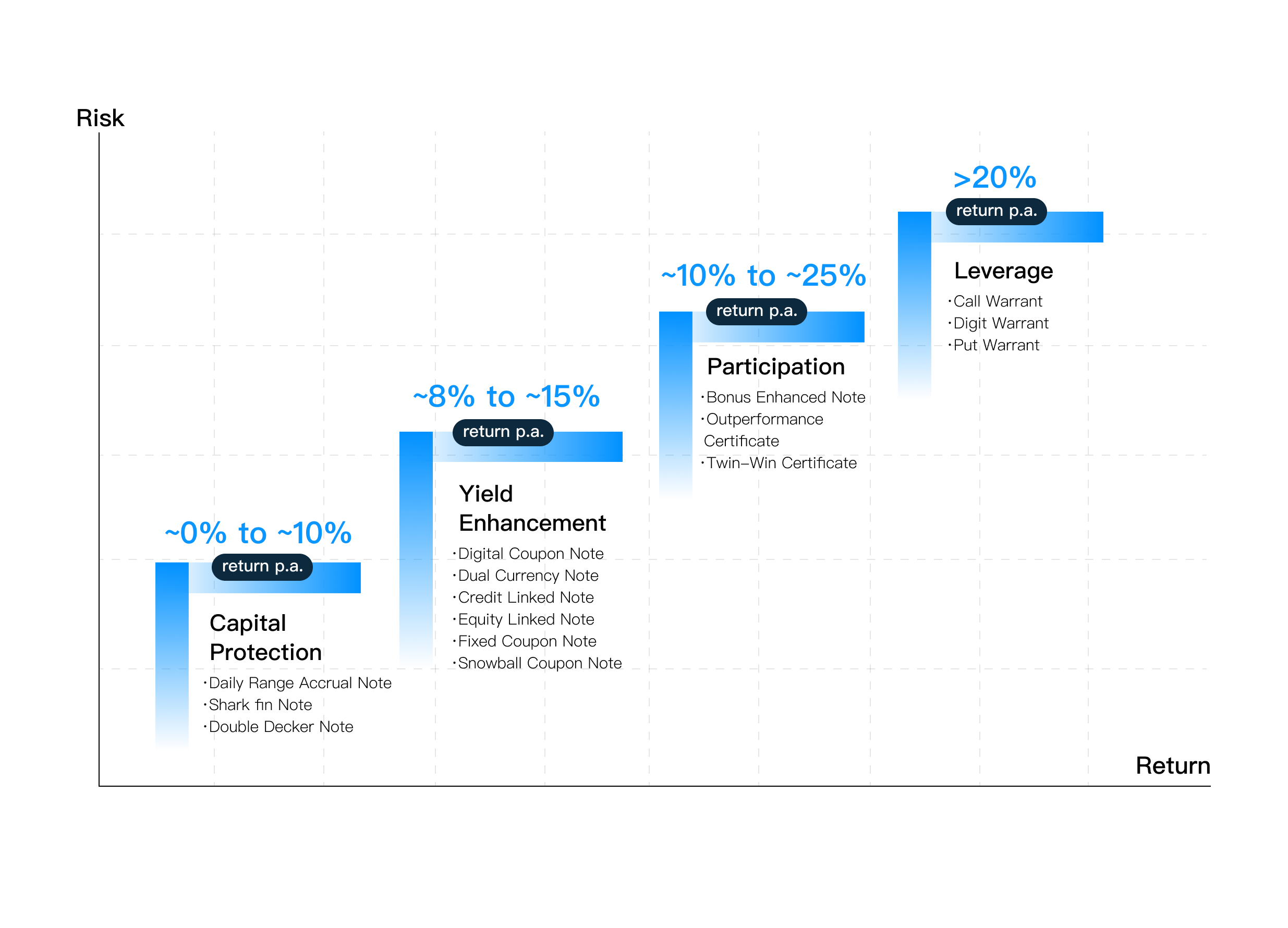

The word “diworsification” was coined by famous portfolio manager Peter Lynch to denote the habit of supplementing a portfolio with investments which, instead of improving risk-adjusted return, add complexity. It demonstrates a common misconception of one of the fundamental pillars of the Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT): diversification.

Whereas the adage “don’t put all your eggs in one basket” exemplifies the foundation of prudent portfolio building, diworsification occurs when an investor adds too many baskets and thus loses sight of the quality and purpose of each one.

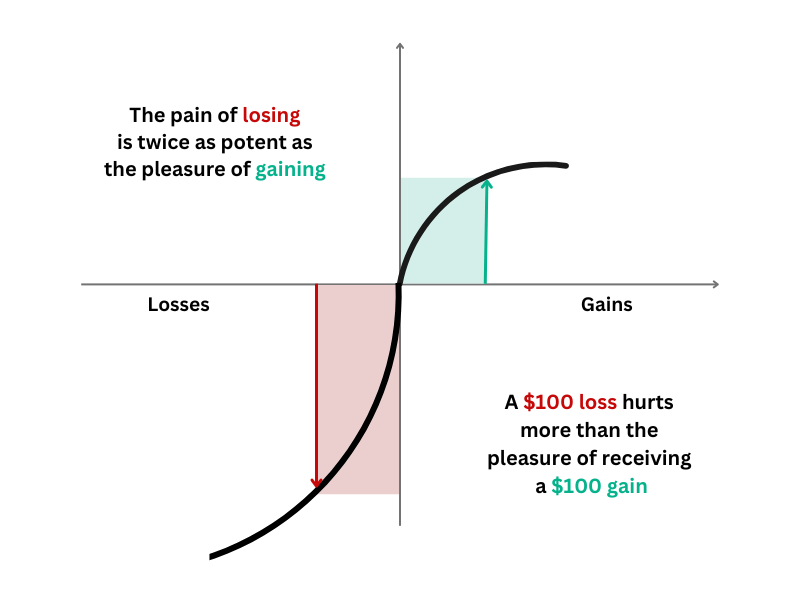

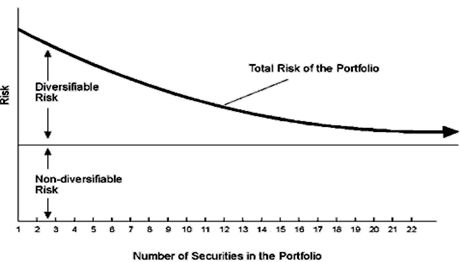

This mistake comes from a fundamental misunderstanding of what diversification actually is. Diversification is not a function of the quantity of assets owned by an investor but of the interconnections of assets. If an investor introduces assets highly correlated with assets owned to a portfolio, the diversification effect of risk is greatly reduced, and a portfolio’s possible return can be diluted.

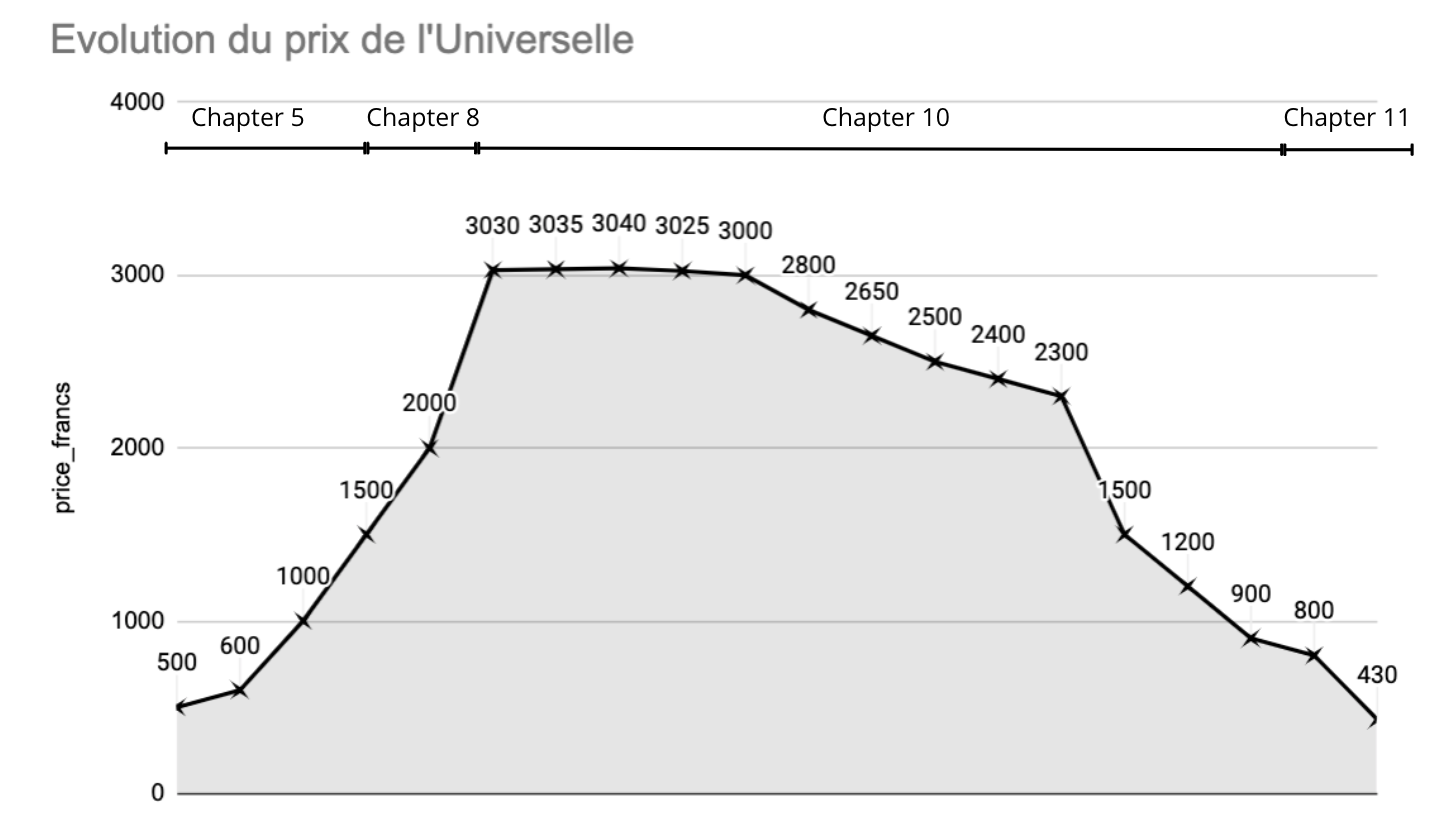

Practical Example

Let’s assume there are two investors.

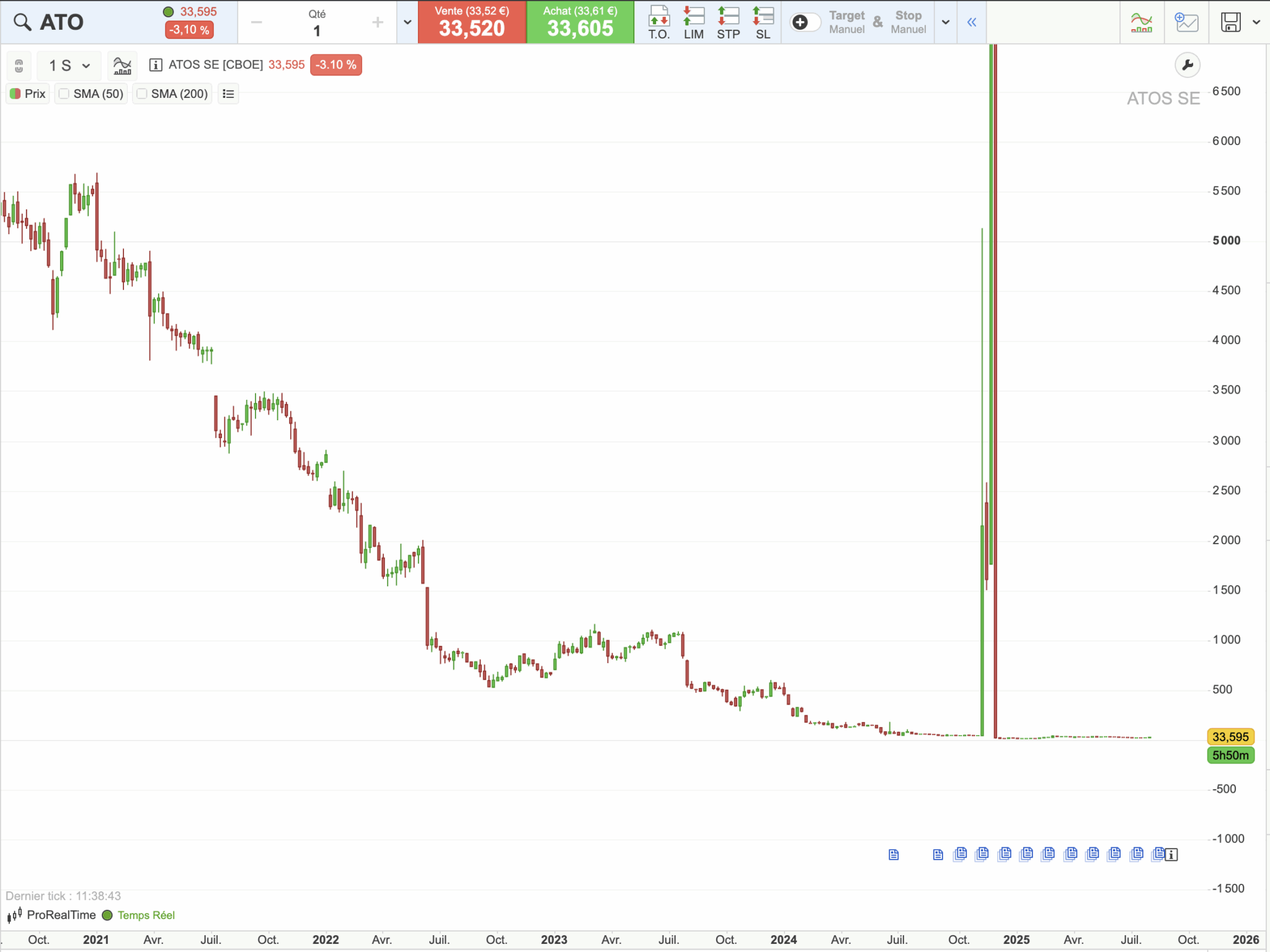

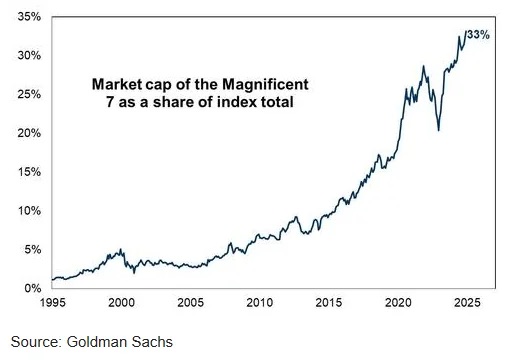

An investor who is interested in the tech industry may hold shares in 20 different software and hardware companies. This portfolio appears diversified on the surface. However, since all the companies are in the same industry, they are all subject to the same market forces and risks. In a decline of the tech industry, it is likely many of the stocks will decline at the same time due to their high correlation.

A second investor maintains a portfolio of three low-cost index funds: one dedicated to the total US stock market, another for the total international stock market, and a third focusing on the total bond market. Despite the simplicity of holding just these three positions, this investor enjoys a far more effective level of diversification in their portfolio. The assets, US stocks, international stocks, and bonds, have a low correlation with one another. Consequently, poor performance in one asset class is likely to be counterbalanced by stable or positive returns in another, resulting in a smoother return profile and a reduction in overall portfolio risk.

The portfolio of the first investor is a perfect case of diworsification. Increasing the number of technology stocks did not do any sort of risk diversification, but it introduced complexity and diluted the effect of performing stocks.

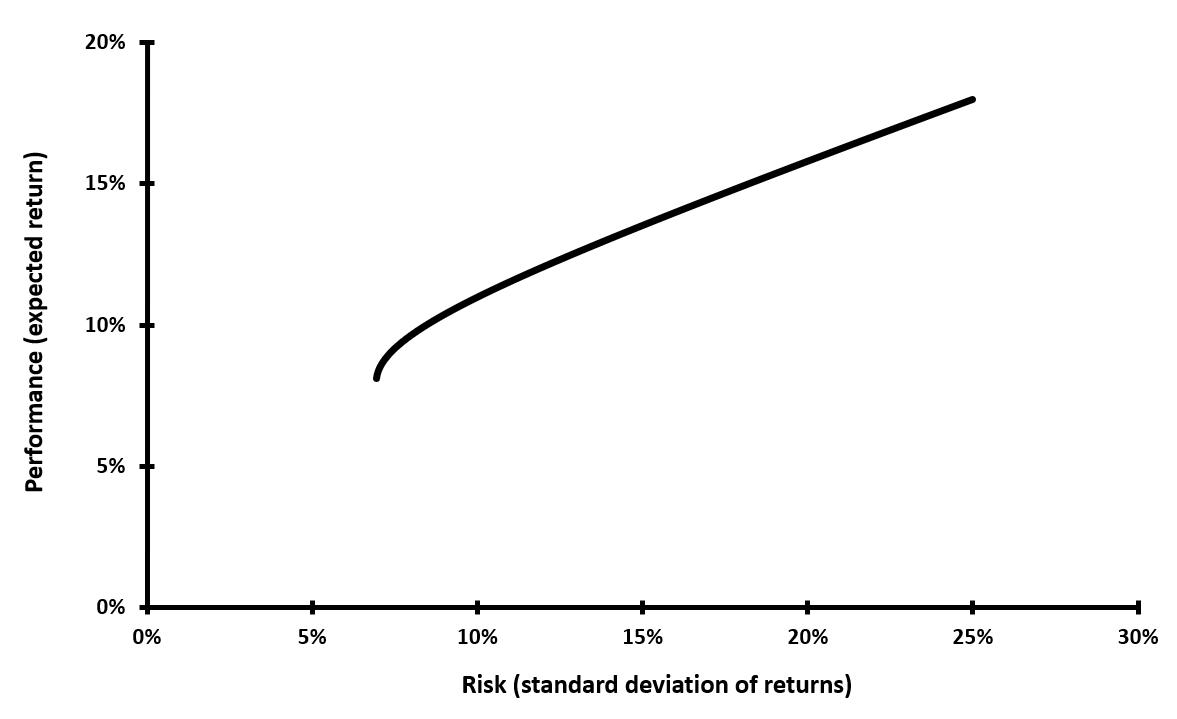

The point at which diversification began to operate to its own harm can be identified with several factors. Diversification’s initial goal is to improve the risk-adjusted return, a concept often evaluated using the Sharpe ratio. Diworsification begins when adding a new asset does not contribute to an improvement in the portfolio’s Sharpe ratio.

You can download the Excel below with a numerical example of the impact of correlation in diversification.

Here is a short summary of what is shown in the Excel spreadsheet.

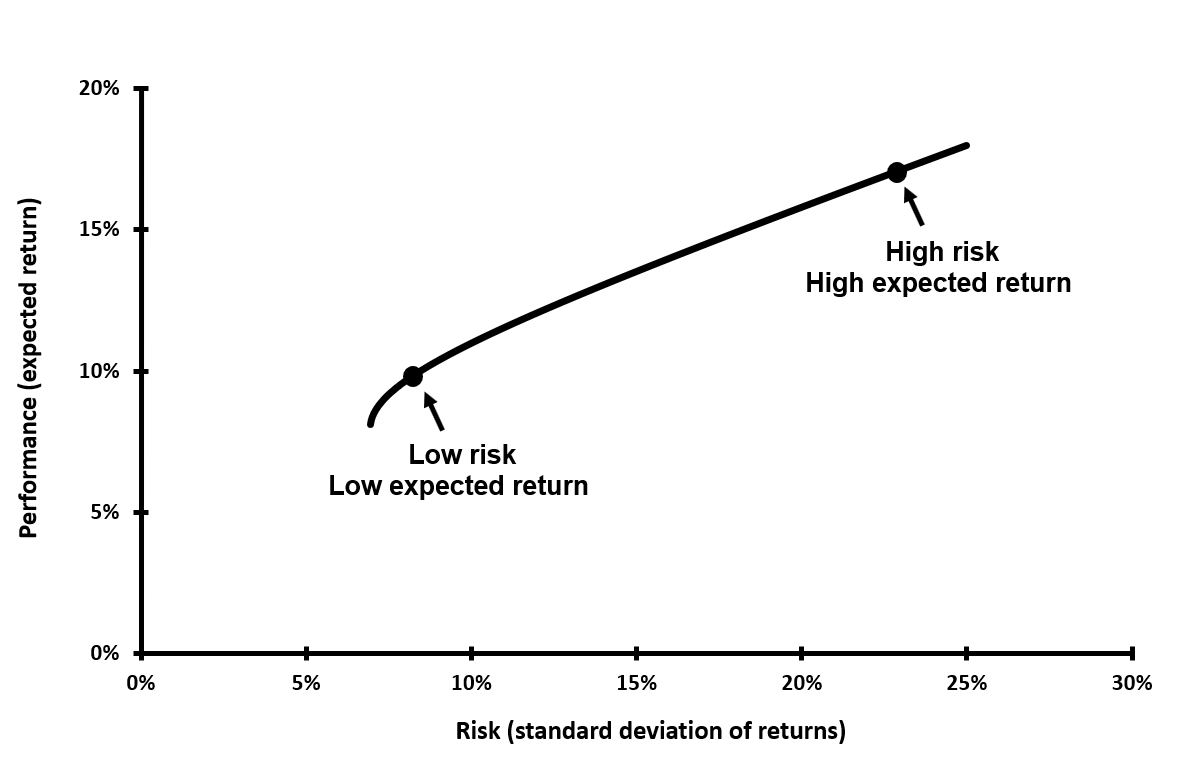

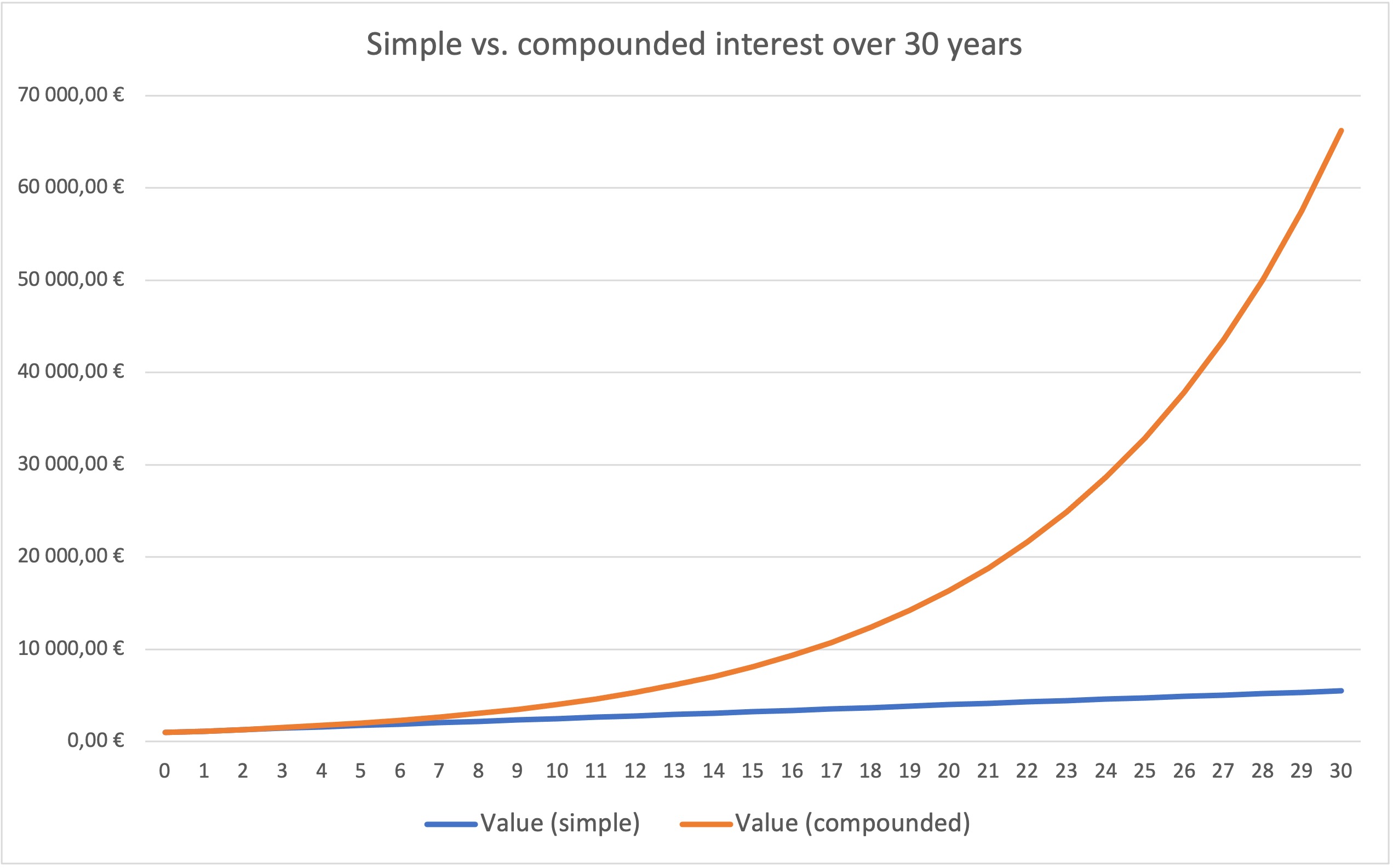

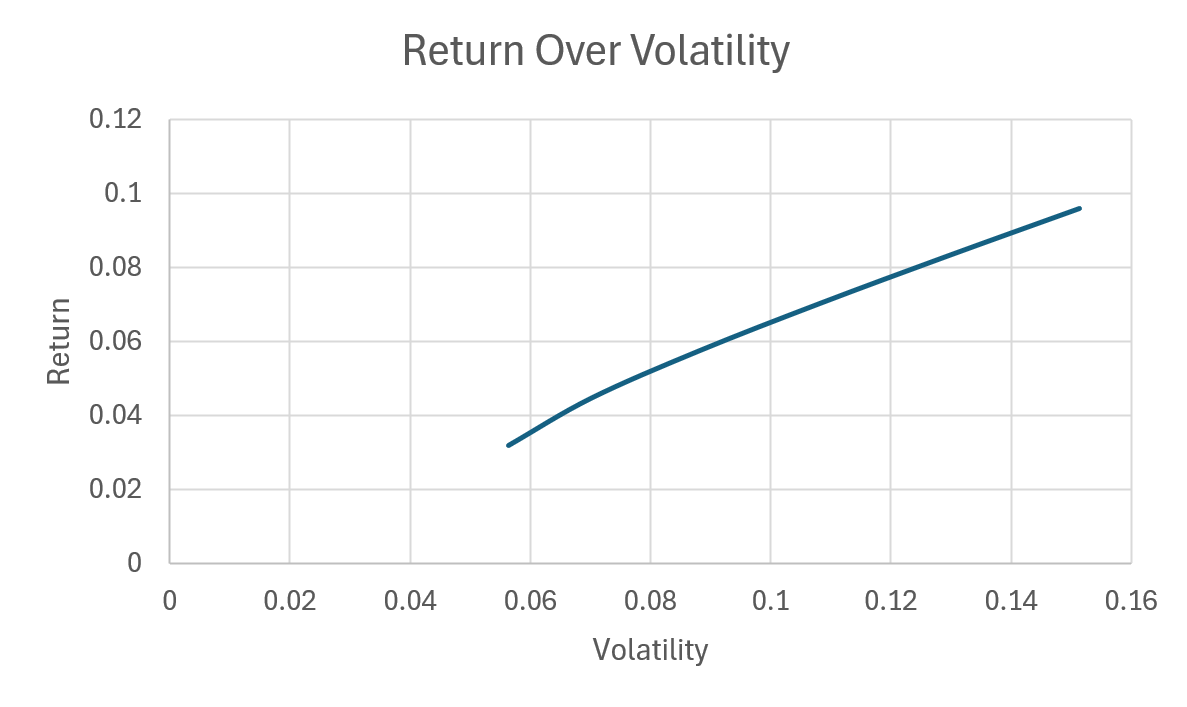

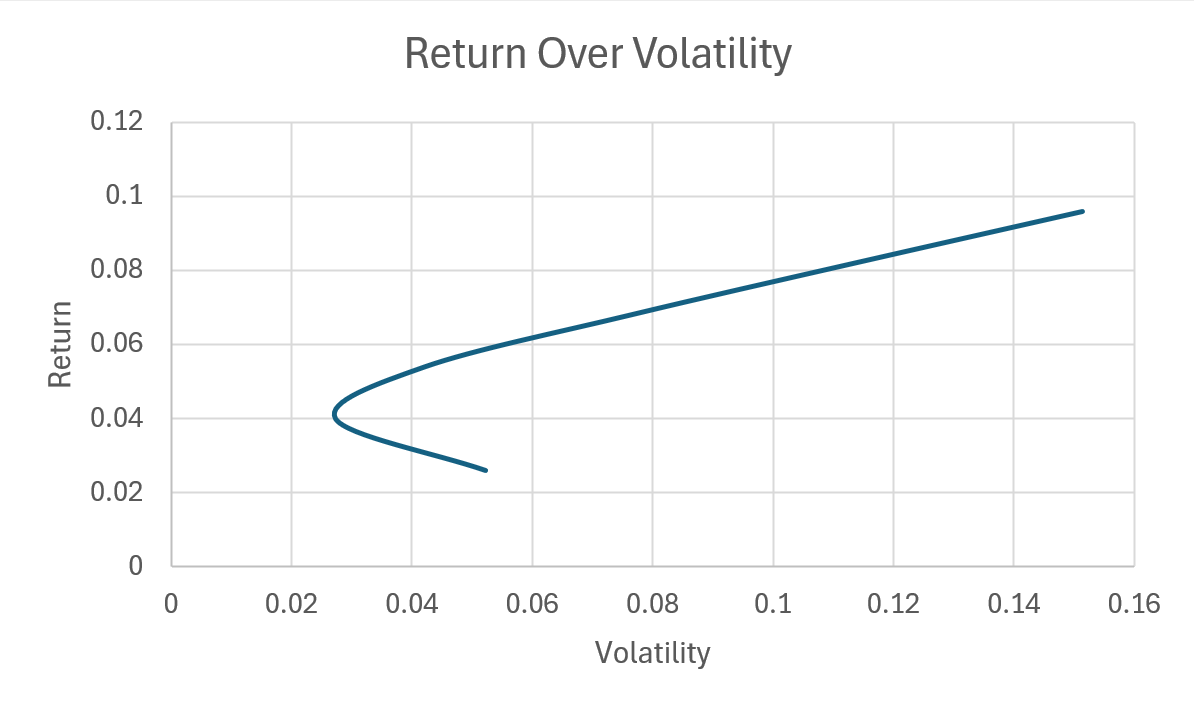

We used two different portfolios, each with 2 assets and both portfolios having a similar expected return and average volatility of assets. The only difference is that the first portfolio has correlated assets, whereas the second portfolio has non-correlated assets.

As you can see in these graphs, the diversification effect is much more potent for the non-correlated portfolio, leading to higher returns for a given volatility.

Target number of assets for a diversified portfolio

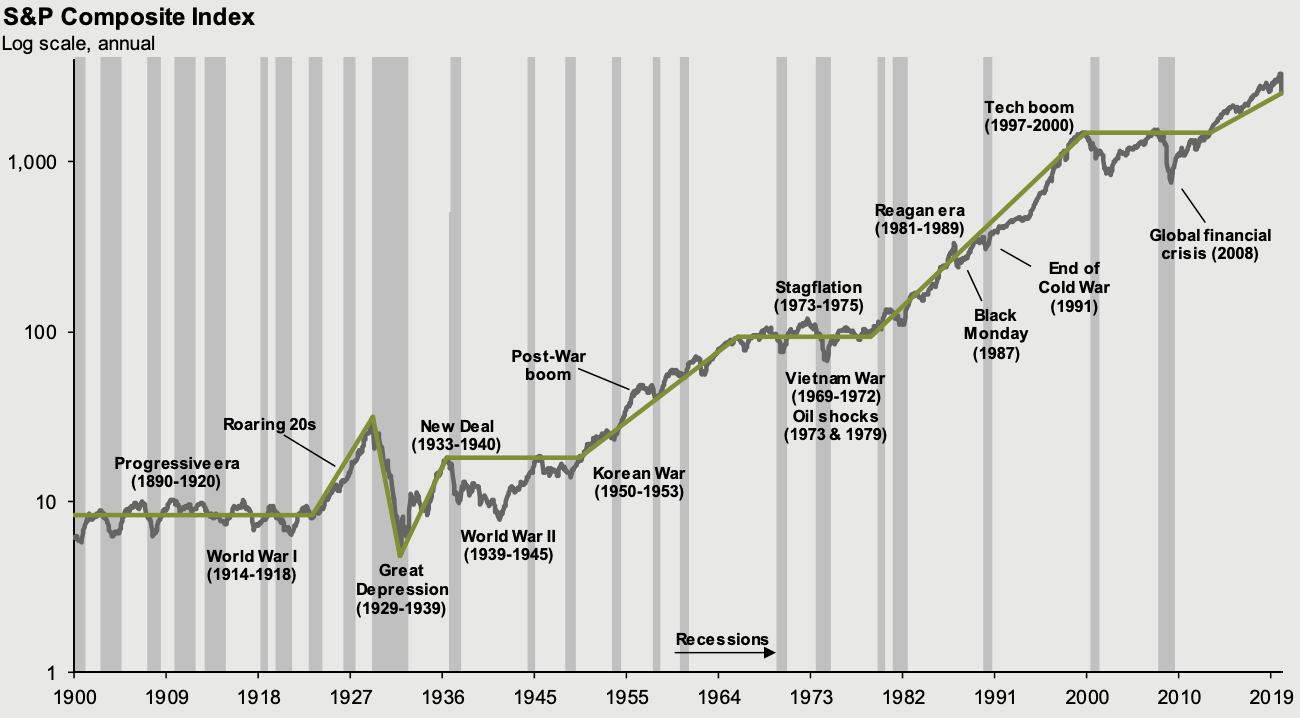

One of the most important considerations when assembling a portfolio is determining the optimal number of assets relative to which greater diversification can be realized prior to the onset of diworsification. Studies of equity markets had indicated that a portfolio of 20 to 30 stocks could diversify away unsystematic risk.

However, this number varies according to different asset classes and the complexity of the assets. In the world of alternative investments, a landmark study, “Hedge fund diversification: how much is enough?,” was published by authors François-Serge Lhabitant and Michelle Learned in 2002, for the Journal of Alternative Investments. The authors aimed to dispel the myth that ‘more is better’ in the complex world of hedge funds. They analyzed the effect of the size of the portfolio on risk and return, determining that although adding to the portfolio reduces risk, the marginal benefits of diversification diminished rapidly.

Importantly they found that adding too many funds could lead to a convergence toward average market returns, effectively eroding the “alpha” (excess return) that investors seek from active management. Furthermore, even when volatility is reduced, other forms of risks, such as skewness and kurtosis, can get worse. The significance of this research is that it offers empirical evidence for the phenomenon of ‘diworsification’—the idea that, after a certain point, adding assets to a portfolio worsens its efficiency.

Crossover from Diversification to Diworsification

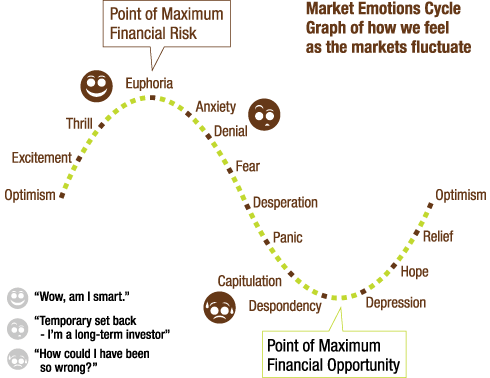

The crossover from diversification to diworsification is normally marked by three main factors.

The first is diluted returns, as the number of assets increases, the performance of the portfolio starts to resemble that of a market index, albeit with elevated costs. The favorable influence of a handful of significant winners is offset by the poor performance of many other investments.

The second is an increase in costs as each asset, and particularly each asset owned through a managed fund, comes with some costs. These can be transaction costs, management fees, or costs of research. The more assets there are, the costs add up and ultimately impose a drag on final performance.

The third is unnecessary complexity as a portfolio with too many holdings becomes hard to keep tabs on, analyze, and rebalance. Which can confuse an investor about his or her asset allocation and expose the portfolio to unnecessary risk.

Causes of Diworsification

The causes for diworsification differ systematically between individual and institutional investors. For individual investors, this fundamental mistake arises from an incorrect understanding of genuine diversification, far too often leading to an emphasis on numbers rather than quality. Behavioral biases, such as familiarity bias, manifested in a preference for investing in well-known names of firms, or fear of missing out, which drives investors toward recently outperforming “hot” stocks, can generate portfolios concentrated in highly correlated securities.

The causes of diworsification for institutional investors are fundamentally different. The asset management business puts on a lot of strain that can lead to diworsification. Fund managers, measured against a comparator index, may prefer to build oversized funds whose portfolios are similar to the index, a process called “closet indexing.” Even if such a strategy reduces the risk of underperforming the comparator and thus losing clients, it also ensures that the fund will not show meaningful outperformance, all the time collecting fees for what is wrongly qualified as active management. In addition, the sale of complex product types like “funds of funds” adds further levels of fees and can mask the fact that the underlying assets are often far from unique.

How to avoid Diworsification

Diworsification doesn’t refer to an abandonment of diversification. Rather, it demands a more intelligent strategy. The emphasis should move from raw number of holdings to the correct asset allocation of the portfolio. The key is to mix asset classes with low or even adverse correlations to each other, for example, stocks, government securities, real estate, and commodities. This method allows for a more solid shelter from price fluctuations than keeping a long list of homogeneous stocks.

A low-cost and efficient means for many investors to achieve this goal is to utilize broad-market index funds and ETFs. These financial products give exposure to thousands of underlying securities representing full asset classes within a single holding, thus eliminating the difficulties and high costs of creating an equivalent portfolio of single assets.

Conclusion

Modern Portfolio Theory provides an intriguing framework for crafting portfolios for investments, and its essential concept of diversification still forms its basis. However, implementing this concept requires thoughtful consideration. Diworsification represents a misinterpretation of the objective, and not an objective to add assets simply in numbers, but to improve the risk-return of the portfolio as a whole.

A successful diversification strategy is built on a foundation of asset allocation to low-correlation assets. By focusing on the quality of diversification rather than the quantity of positions, investors can create portfolios that are closer to what they want, avoiding unnecessary costs and lower returns of a diworsified outcome.

Why should I be interested in this post?

Diworsification is a trap that should be avoided, and is really easy to avoid when you understand the mechanisms at work behind it.

Related posts on the SimTrade blog

▶ All posts about Financial techniques

▶ Raphael TRAEN Understanding Correlation

▶ Youssef LOURAOUI Minimum Volatility Portfolio

Useful resources

Lhabitant, F.-S., M. Learned (2002) Hedge fund diversification: how much is enough? Journal of Alternative Investments, 5(3):23-49.

Lynch P., J. Rothchild (2000) One up on Wall Street. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Markowitz, H. (1952). Portfolio Selection. The Journal of Finance, 7(1), 77–91.

About the author

This article was written in November 2025 by Yann TANGUY (ESSEC Business School, Global Bachelor in Business Administration (GBBA), 2023-2027).