Value Factor

In this article, Youssef LOURAOUI (ESSEC Business School, Global Bachelor of Business Administration, 2017-2021) presents the value factor, which is based on a risk factor that aims to get exposure to undervalued firms in relation to their industry competitors in order to benefit from the potential upside.

This article is structured as follows: we begin by defining the value factor and reviewing academic studies. The MSCI Value Factor Index, which is well used as a benchmark in the asset management industry, is next presented in terms of performance, risk-return trade-off, and behavior during the Covid-19 crisis. We showcase the ETF market for investors looking to profit from the value factor.

Definition

In the world of investing, a factor is any aspect that helps explain an asset’s long-term risk and return performance. In the late 1970s, the portfolio management industry’s objective was to capture the market return on a portfolio. As a result of Markowitz and Tobin’s earlier research, William Sharpe, John Lintner, and Jan Mossin independently developed the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). Because it enabled investors to properly value assets in terms of systematic risk, the CAPM was a significant evolutionary step forward in the theory of capital market equilibrium (Mangram, 2013). Eugene Fama and Kenneth French, following the CAPM’s original work, developed the Fama-French Three-Factor model in 1993 to solve the CAPM’s inadequacies. It claims that, in addition to the market risk component of the CAPM, two other factors have an effect on the returns on securities and portfolios: market capitalization (called the “size” factor) and the book-to-market ratio (referred to as the “value” factor). Other factor characteristics were developed to capture some additional performance as financial research advanced and significant contributions were made.

The value factor is based on a risk factor that aims to get exposure to undervalued firms in relation to their industry competitors in order to benefit from the potential upside (Graham, 1971).

Academic research

The most influential academic studies in the value investing literature may be traced back to Fama and French’s foundational work. In 1993, Eugene Fama and Kenneth French created the Fama-French Three-Factor model in response to the CAPM’s shortcomings. It claims that, in addition to the market risk component introduced by the CAPM, two more variables affect the returns on securities and portfolios: market capitalization (often referred to as “size”) and book-to-market ratio (referred to as the “value” factor). According to Fama and French, the primary justification for include these qualities is that both size and book-to-market (BtM) ratios are related to the business issuing the securities’ economic fundamentals (Fama and French, 1993).

Fama and French assert in 2014 that their initial 1993 three-factor model does not sufficiently explain for some observed discrepancies in anticipated returns. As a result, Fama and French added two more factors to their three-factor model: profitability and investment. These two elements are justified by the dividend discount model’s (DDM) theoretical implications, which assert that profitability and investment contribute to the explanation of the returns obtained from the HML element in the first model (Fama & French, 2015).

Business investors analysis

Benjamin Graham’s book: “The intelligent investor”

The cornerstone of value investing is the belief that low-cost stocks beat higher-cost firms over time. Value is a “pro-cyclical” element, which means that it has tended to gain during periods of economic boom. The seminal work on the value factor is undoubtedly the contribution of Benjamin Graham in his work “The intelligent investor”, one of the most adored and glorified books in finance and considered as a menhir of modern investment (Graham, 1971). According to the value investment approach, he considers that intelligence is not the most important parameter in investing. There’s evidence that a high IQ and a college degree aren’t enough to create a smart investor. Long-Term Capital Management L.P., a hedge fund operated by a squadron of mathematicians, computer scientists, and two Nobel Laureates in Economics (Myron Scholes and Robert C. Merton), lost more than $2 billion in a couple of weeks in 1998 on a massive bet that the bond market would return to “normal.” However, the bond market continued to become increasingly anomalous, and LTCM had borrowed so much money that its failure threatened to capsize the entire financial system. Graham’s work deconstructs several interesting notions that allow one to make a well-reasoned investment decision and to escape from the various cognitive biases that can lead to taking more dangerous positions in the markets (Graham, 1971). In a nutshell, among the most important points for a value investor are (Graham, 1971):

- A stock is more than a ticker symbol; it’s a share of ownership in a real firm with a value apart from its share price. The stock market is a pendulum that swings back and forth between unjustified optimism (which pushes up stock prices) and unjustified pessimism (which drives down stock prices) (which makes them too cheap)

- A savvy investor buys from pessimists and sells to optimists. The present price of an investment determines its future value. The higher the price you pay, the lower your return

- No investor, no matter how careful they are, will ever eliminate the possibility of making a mistake. Only by adhering to Graham’s “margin of safety,” that is, never overpaying for an investment, no matter how attractive it seems, can you decrease your odds of making a mistake

- The key to financial success is personal growth in terms of how an investor reacts to market events without including emotions in the decision-making process, as this has a negative impact

Benjamin Graham and David Dodd’s book: “Security Analysis”

With the release of Security Analysis in 1934, Benjamin Graham and David Dodd permanently altered the philosophy and practice of investing. The United States, and indeed the rest of the globe, was engulfed in the Great Depression, a period of unprecedented financial turmoil (Graham & Dodd, 2010). The authors replied with a thorough modification in 1940. Many investors regard the second edition of Security Analysis to be the ultimate word from the most prominent investing philosophers of our time. Security Analysis is still considered the standard text for stock and bond analysis across the world. The work of Graham with “The Intelligent Investor” and “Security Analysis” is regarded as the “bible” of value investing. In a nutshell, the book describes the following aspects (Graham & Dodd, 2010):

- The purpose of security analysis is to provide critical information about a stock or bond in an informative and useful manner to a prospective owner; and to make accurate judgments about a security’s safety and attractiveness relative to its current price range based on facts and criteria.

- Graham and Dodd describe investing as follows: “An investment activity is one that, after careful analysis, guarantees the safety of money and an acceptable rate of return.” Speculative operations are those that do not comply with these requirements”.

- Investors are classified into two types: those who are defensive and those who are adventurous. The former’s portfolio is comprised of a diverse selection of high-price stocks purchased at a discount. The entrepreneurial investor understands the value between market and intrinsic value, which enables him or her to analyze specific stocks in type of and profit from price-to-value discrepancies.

- An analysis of a security involves two distinct types of factors: quantitative and qualitative. The former domain should encompass capital structure, earnings power, dividend distributions, and operational effectiveness. The qualitative domain is more ‘fluffy’; it encompasses the ‘character’ of the business, its market position(s), and an appraisal of the management team, among other things. Quantitative data is only useful when accompanied by qualitative analysis.

- The most critical word in the book is “earnings power.” The authors emphasize the significance of estimating a company’s real future earnings based on its historical earnings (adjusted for one-time events) as well as its vulnerability to factors such as cyclical swings.

Example of a “value” stock

A value stock is one that trades at a lower price than the company’s actual performance. Because the price of the underlying shares may not reflect the company’s performance, value stock investors seek to profit from market inefficiencies (Investopedia, 2021). Value stocks, for example, include big money center banks. JPMorgan Chase & Co. (JPM) is a value stock that trades at a substantial discount to the market based on earnings.

MSCI Value Factor Index

MSCI Factor Indexes are rules-based, transparent indexes that target equities with favorable factor qualities, as determined by academic discoveries and empirical outcomes, and are designed for easy implementation, replicability, and usage in both standard indexed and active portfolios. The stock price as a multiple of business earnings, the price as a multiple of dividends paid, the price as a multiple of book value, and other “ratio descriptors” are all examples of value. Academics and investors disagree on which business best symbolizes a value company, resulting in a market potential for a range of investment products. On a sector-by-sector basis, the MSCI Enhanced Value Index uses three valuation ratio descriptors:

- Forward price to earnings (Fwd P/E)

- Enterprise value/operating cash flows (EV/CFO)

- Price to book value (P/B)

The index tries to avoid the problems of value investing, such as “value traps,” or stocks that look inexpensive but do not grow in value. The research demonstrates that whole-firm valuation metrics like enterprise value have decreased concentration in highly leveraged businesses (those that have taken on a lot of debt).

Performance of the MSCI Value Factor Index

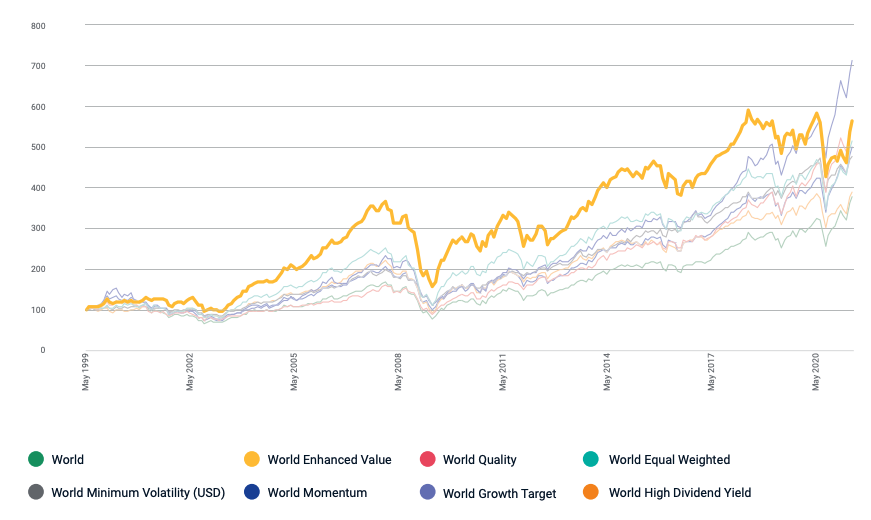

Figure 1 compares the MSCI Value Factor Index’s performance to those of other factors from May 1999 to May 2020. All indices are rebalanced on a 100-point scale to ensure consistency in performance and to facilitate factor comparisons.

Figure 1. Performance of the MSCI Value Factor Index from 1999-2020.

Source: MSCI Factor research (2021).

Since 1999, the MSCI World Enhanced Value Index has achieved excess returns above the MSCI World Index, with a 1.99 percent annual return over the MSCI World Index as seen above. (MSCI Factor research, 2021).

Risk-return profile of MSCI Value Factor Index

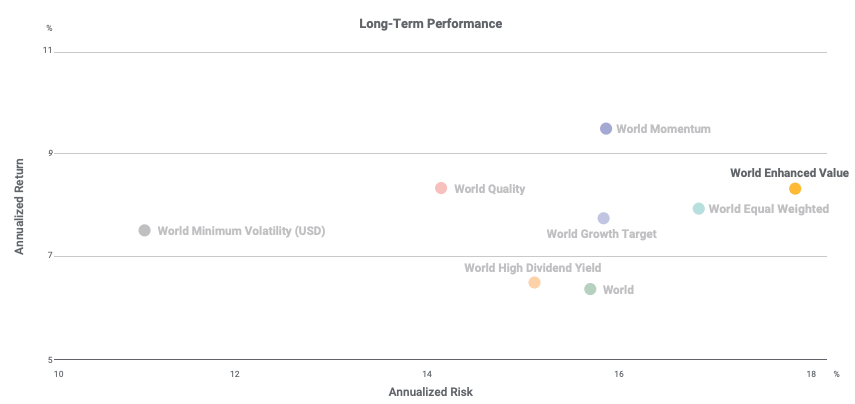

Figure 2 shows the MSCI Value Factor Index compared to other factors over the period May 1999 – May 2020 in terms of risk/reward. The risk-return tradeoff states that the potential return rises with an increase in risk. Individuals connect low levels of uncertainty about future returns with low potential returns, while high levels of uncertainty or risk are associated with large potential returns. According to the risk-tradeoff trade-off, an investor’s money can generate higher returns only if the investor is willing to endure a higher risk of loss (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Risk-return profile of MSCI Value Factor Index compared to a peer group.

Source: MSCI Factor research (2021).

The basis of value investing is identifying stocks whose prices appear to understate their fundamental worth. While many institutional investors may agree, value-index strategies are executed in a number of ways. Incorporating the value factor into a portfolio might potentially boost returns and function as a well-researched performance vector (MSCI Factor research, 2021).

Behavior of the MSCI Value Factor Index during the Covid-19 crisis

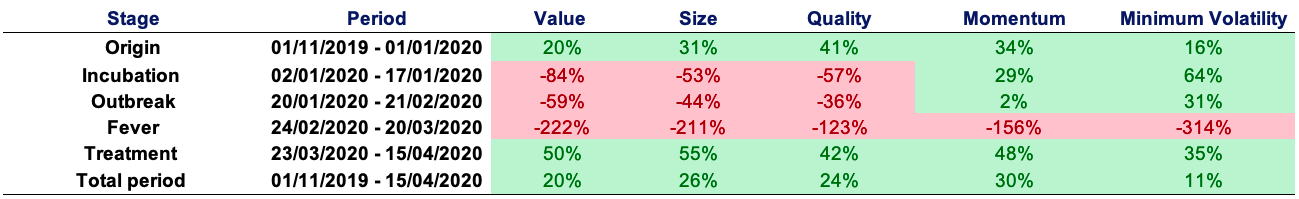

The Covid-19 crisis has not only caused significant social and economic suffering, but it had also an impact on financial markets. To study the behavior of the factors during the Covid-19 crisis, we compute the return of the MSCI Factor indexes during the different stages of the crisis. The MSCI Factor indexes are: value, size, quality, momentum and minimum volatility. Following Pagano et al. (2020) and Hasaj and Sherer (2021), we decompose the Covid-19 crisis into five stages: origin, incubation, outbreak, fever, and treatment. Each stage is described below.

- Origin (01/11/2019 – 01/01/2020): the first instances are reported in Wuhan, China.

- Incubation (02/01/2020 – 17/01/2020): during this phase, the number of patients began to rise at a faster rate, raising concerns about the disease’s severity.

- Outbreak (20/01/2020 – 21/02/2020): the number of cases rose to the point that the World Health Organization (WHO) decided that this illness may pose a major threat to the world’s population, and the pandemic was proclaimed.

- Fever (24/02/2020 – 20/03/2020): markets are extremely volatile, owing to government restrictions aimed at flattening the infection curve, with the decision to impose a lockdown in numerous nations as the most notable measures, among others.

- Treatment (23/03/2020 – 15/04/2020): most of this turnaround occurs between March and June 2020, which corresponds with the start of good news about the discovery and widespread use of the vaccine.

Table 1 gives the performance of the MSCI factor indexes during the different stages of the Covid-19 crisis. Performance is measured by the return computed on the time-period of each stage, and then annualized for comparison across the different stages. We use data are from Thomson Reuters.

Table 1. Performance of the MSCI factor indexes during the Covid-19 crisis.

Source: computation by the author. Data source: Thomson Reuters.

The value factor has performed not quite well in comparison to the other factors, finishing fourth out of five throughout the time period studied. Additionally, our study demonstrates that the value factor was the poorest performer during the incubation and outbreak stages and the second worst performer during the fever stage. This demonstrates the value factor’s instability during the Covid-19 crisis, which acted as a stress test.

ETFs to capture the Value factor

Let us recall that an Exchange-Traded Fund (ETF) is an investment vehicle that seeks to mirror the performance of a benchmark like an equity index and is traded on a continuous basis during the day like stocks. By investing in ETFs, an investor gains access to a plethora of diversification options through several asset classes (equity, bonds, currency, commodity, real estate, etc.).

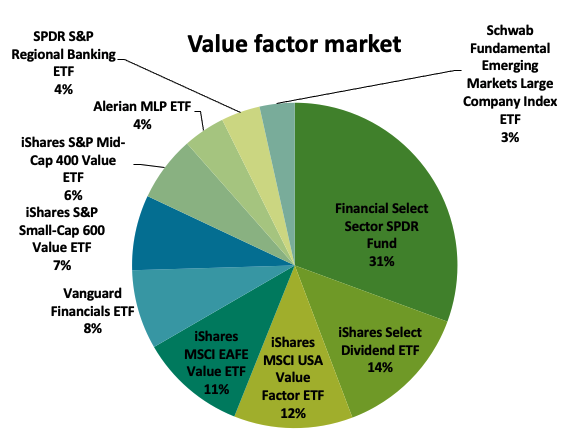

Figure 3 gives the overall ETF distribution of the major providers of value factor ETFs in terms of asset under management. By examining the market overview for minimal volatility factor investments, we can observe Blackrock (iShares) and State Street Global Advisors as the most dominant players in this segment. They hold nearly 50% and 34% respectively of the overall value factor ETF market, which underpins nearly 117B$ of the overall 138B$ in terms of market value for the value factor ETF market retained in this benchmark.

Figure 3. Value factor ETF market.

Source: etf.com (2021).

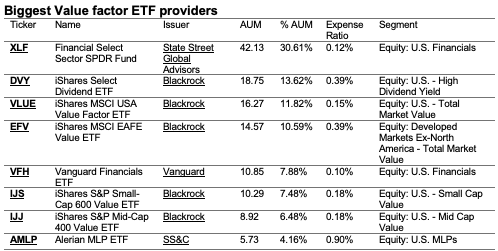

Table 2 gives more detailed information about the biggest value factor ETF providers: the asset under management (AUM), expense ratio (ER) and the segment for the investments.

Table 2. Ranking of the biggest Value ETF providers.

Source: etf.com (2021).

Why should I be interested in this post?

If you are an undergraduate or graduate student in a business school or at the university, you may have seen in your 101 finance course the CAPM related to the market factor. This post makes aware of the existence of another risk factor priced by the market.

If you are an investor, you may consider adding an exposure to value factor to enhance the overall portfolio return.

Related posts on the SimTrade blog

▶ Youssef LOURAOUI Minimum Volatility

▶ Youssef LOURAOUI Size Factor

▶ Youssef LOURAOUI Yield Factor

▶ Youssef LOURAOUI Momentum Factor

▶ Youssef LOURAOUI Quality Factor

▶ Youssef LOURAOUI Growth Factor

Useful resources

Academic articles

Fama, E.F. French, K.R., 1992. The Cross-Section of Expected Stock Returns. The Journal of Finance , 47: 427-465.

Fama, E.F. French, K.R., 2015. A five-factor asset pricing model, Journal of Financial Economics , 116(1): 1-22.

Graham, B., Dodd, D., 1934. Security Analysis. 6th Edition, McGraw Hill.

Graham, B., 1949. The Intelligent Investor. 4th edition, Harper Business Essentials.

Hasaj, M., Sherer, B., 2021. Covid-19 and Smart-Beta: A Case Study on the Role of Sectors”. EDHEC-Risk Institute Working Paper.

Mangram, M.E., 2013. A simplified perspective of the Markowitz Portfolio Theory. Global Journal of Business Research, 7(1): 59-70.

Pagano, M., Wagner, C., Zechner, J. 2020. Disaster Resilience and Asset Prices, Working paper.

Business analysis

etf.com, 2021. Biggest Value Factor ETF providers.

MSCI Investment Research, 2021. Factor Focus: Value

Investopedia, 2021. Value Stock Definition.

About the author

The article was written in September 2021 by Youssef LOURAOUI (ESSEC Business School, Global Bachelor of Business Administration, 2017-2021).

Pingback: Yield Factor - SimTrade blogSimTrade blog

Pingback: Minimum Volatility Factor - SimTrade blogSimTrade blog

Pingback: Momentum Factor - SimTrade blogSimTrade blog

Pingback: Size Factor - SimTrade blogSimTrade blog

Pingback: Quality Factor - SimTrade blogSimTrade blog

Pingback: Growth Factor - SimTrade blogSimTrade blog

Pingback: Origin of factor investing - SimTrade blogSimTrade blog

Pingback: Factor Investing - SimTrade blogSimTrade blog

Pingback: VIX index - SimTrade blogSimTrade blog