Size Factor

In this article, Youssef LOURAOUI (ESSEC Business School, Global Bachelor of Business Administration, 2017-2021) presents the size factor, which is based on a risk factor that aims to capture the documented outperformance of small-cap firms compared to larger enterprises.

This article is structured as follows: we begin by defining the size factor and reviewing academic studies. The MSCI Size Factor Index, which is well used as a benchmark in the asset management industry, is next presented in terms of performance, risk-return trade-off, and behavior during the Covid-19 crisis. We showcase the ETF market for investors looking to profit from the size factor.

Definition

In the world of investing, a factor is any aspect that helps explain an asset’s long-term risk and return performance. In the late 1970s, the portfolio management industry’s objective was to capture the market return on a portfolio. As a result of Markowitz and Tobin’s earlier research, William Sharpe, John Lintner, and Jan Mossin independently developed the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). Because it enabled investors to properly value assets in terms of systematic risk, the CAPM was a significant evolutionary step forward in the theory of capital market equilibrium (Mangram, 2013).

Eugene Fama and Kenneth French, following the CAPM’s original work, developed the Fama-French Three-Factor model in 1993 to solve the CAPM’s inadequacies. It claims that, in addition to the market risk component of the CAPM, two other factors have an effect on the returns on securities and portfolios: market capitalization (called the “size” factor) and the book-to-market ratio (referred to as the “value” factor). Other factor characteristics were developed to capture some additional performance as financial research advanced and significant contributions were made.

The Size factor has captured the long-run proclivity of small-cap firms to outperform larger enterprises. The work of Banz (1981) adds another piece to the growing puzzle. It evaluates the link between a firm’s overall market value and its return on common shares. The findings indicate that, on average, small businesses common stock generated greater risk-adjusted returns than large firms’ common stock throughout the 1936 – 1975 period (Banz, 1981). This impact is referred to as the “size effect”.

Academic research

Rolf Banz, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Chicago at that time, found the size factor in US stocks in 1981. The size effect’s proponents provide many explanations for it. Banz stated that it is the result of a weakness in the capital asset pricing model (CAPM, the typical approach for forecasting risk and return on stock investments) or a lack of information regarding businesses that receive minimal analyst attention. After economists Eugene Fama and Kenneth French incorporated size as a critical component of their renowned three-factor model, size research exploded (MSCI Factor research, 2021).

Empirical studies

According to academic literature, the single-period capital asset pricing model (henceforth CAPM) postulates a straightforward linear connection between a security’s projected return and market risk. While direct testing has proved inconclusive, emerging evidence supports the possibility of other asset price variables.

For the period 1936-1977, Litzenberger and Ramaswamy (1979) demonstrate a substantial positive association between dividend yield and return on common stocks. Basu (1977) establishes a link between price-earnings ratios and risk-adjusted returns (Banz, 1981). He interprets his findings as evidence of market inefficiency; however, market efficiency tests are frequently conducted in conjunction with tests of the efficient market hypothesis and a particular equilibrium connection. Thus, some of the abnormalities ascribed to a lack of market efficiency may easily be the consequence of model misspecification. However, because the study’s findings are not based on a particular theoretical equilibrium model, it is impossible to clearly establish whether market value matters in and of itself or whether it is only a proxy for undiscovered actual extra elements linked with market value (Banz, 1981).

According to the data given in this paper, the CAPM is misspecified. Over a forty-year period, tiny NYSE businesses have generated considerably higher risk-adjusted returns than large NYSE enterprises (Banz, 1981). This size impact is not linear in market proportion (or market proportion log) but is most evident for the sample’s smallest companies. Additionally, the impact is not very stable over time. A comparison of the ten-year subperiods reveals significant variations in the magnitude of the size factor’s coefficient (Banz, 1981).

Such an impact has no theoretical basis. Banz asserts that we don’t even know if the factor is size itself or if size is only a proxy for one or more genuine but unknown factors that are linked with size (Banz, 1981). However, it is feasible to make certain hypotheses and even debate some aspects for which size is a proxy. Reinganum’s (1980) recent study has ruled out one obvious candidate: the price-earnings (P/E) ratios. He discovers that the P/E effect, as reported by Basu (1977), vanishes when he controls for size for both NYSE and AMEX stocks, but that there is a significant size effect even when he controls for the P/E ratio, implying that the P/E ratio effect is a proxy for the size effect and not the other way around (Banz, 1981).

Naturally, there are still a vast number of potential elements to evaluate. Thus, a lack of knowledge about small businesses results in less diversification and thus greater returns on ‘undesirable’ small business stocks (Banz, 1981). It may be tempting to use the size effect as the basis for a theory of mergers – big businesses may pay a premium for small firms’ shares because they can discount the same cash flows at a lower discount rate. Naturally, this may turn out to be total nonsense if it is demonstrated that size is only a proxy. While this informal model fits the empirical data, it is only speculation. The size effect occurs, but its cause is unknown. It should be regarded with caution until an answer is found (Banz, 1981).

MSCI Size Factor Index

MSCI Factor Indexes are rules-based, transparent indexes that target equities with favorable factor qualities, as determined by academic discoveries and empirical outcomes, and are designed for easy implementation, replicability, and usage in both standard indexed and active portfolios. The MSCI Equal Weighted Indexes tend to favor smaller cap firms. At each rebalance date, index components are weighted equally, thereby eliminating the influence of that constituent’s price (high or low) from the index. Size is a “pro-cyclical” element, which means it has historically benefited from periods of economic boom.

For decades, institutional investing has included a size premium. It has been a key component of several factor-based indexes during the last few years. MSCI Equal Weighted Indexes tend to favor smaller sized firms in comparison to the benchmark parent index (MSCI Factor research, 2021). At each rebalancing date, index components are weighted equally, thereby eliminating the influence of a constituent’s price (high or low) on the index.

Performance of the MSCI Size Factor Index

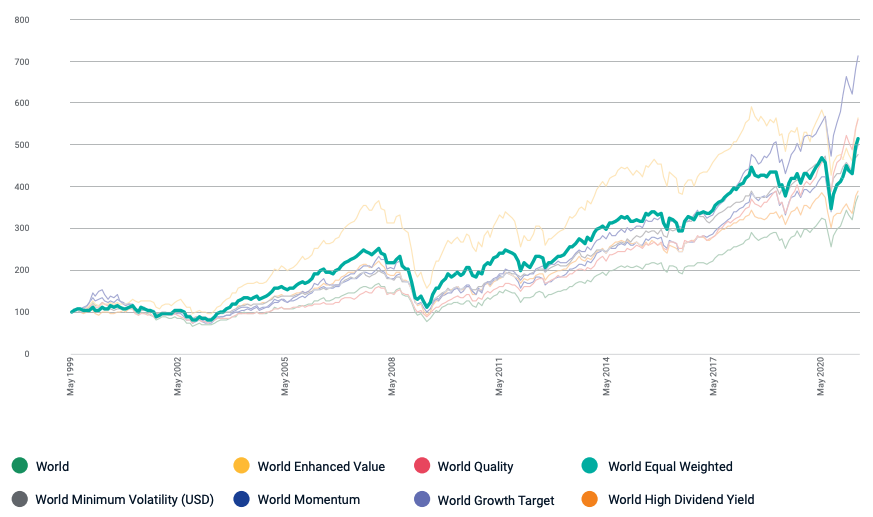

Figure 1 compares MSCI World Equal Weighted Index (Size factor) performance to those of other factors from May 1999 to May 2020. All indices are rebalanced on a 100-point scale to ensure consistency in performance and to facilitate factor comparisons.

Figure 1. Performance of the MSCI Size Factor Index from 1999-2020.

Source: MSCI Factor research (2021).

Over the long term, the MSCI World Equal Weighted Index (Size factor) has traditionally provided excess returns, with an annual return of 1.54 percent over the MSCI World Index since 1999 (MSCI Factor research, 2021).

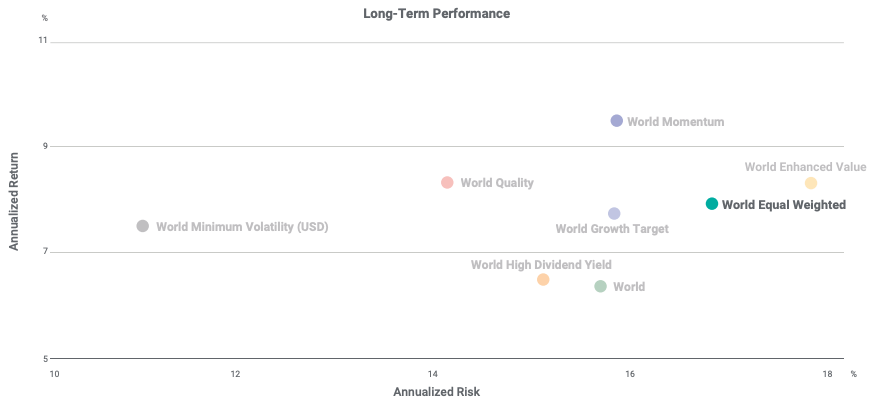

Risk-return profile of MSCI Size Factor

Figure 2 shows the MSCI World Equal Weighted Index (Size factor) compared to other factors over the period May 1999 – May 2020 in terms of risk/reward. The risk-return trade-off states that the potential return rises with an increase in risk. Individuals connect low levels of uncertainty about future returns with low potential returns, while high levels of uncertainty or risk are associated with large potential returns. According to the risk-return trade-off, an investor’s money can generate higher returns only if the investor is willing to endure a higher risk (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Risk-return profile of MSCI Size Factor Index compared to a peer group.

Source: MSCI Factor research (2021).

Behavior of the MSCI Size Factor Index during the Covid-19 crisis

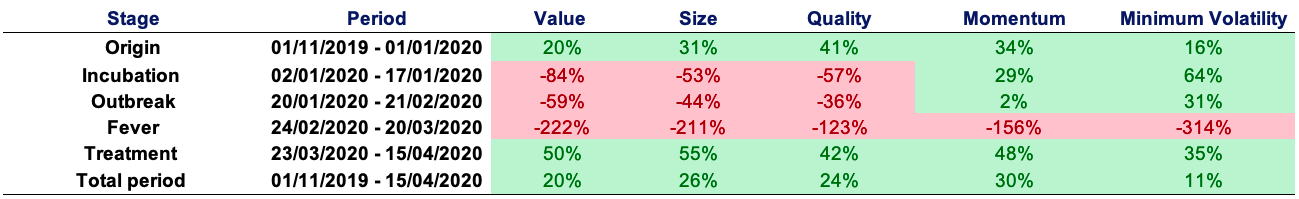

The Covid-19 crisis has not only caused significant social and economic suffering, but it had also an impact on financial markets. To study the behavior of the factors during the Covid-19 crisis, we compute the return of the MSCI Factor indexes during the different stages of the crisis. The MSCI Factor indexes are: value, size, quality, momentum and minimum volatility. Following Pagano et al. (2020) and Hasaj and Sherer (2021), we decompose the Covid-19 crisis into five stages: origin, incubation, outbreak, fever, and treatment. Each stage is described below.

- Origin (01/11/2019 – 01/01/2020): the first instances are reported in Wuhan, China.

- Incubation (02/01/2020 – 17/01/2020): during this phase, the number of patients began to rise at a faster rate, raising concerns about the disease’s severity.

- Outbreak (20/01/2020 – 21/02/2020): the number of cases rose to the point that the World Health Organization (WHO) decided that this illness may pose a major threat to the world’s population, and the pandemic was proclaimed.

- Fever (24/02/2020 – 20/03/2020): markets are extremely volatile, owing to government restrictions aimed at flattening the infection curve, with the decision to impose a lockdown in numerous nations as the most notable measures, among others.

- Treatment (23/03/2020 – 15/04/2020): most of this turnaround occurs between March and June 2020, which corresponds with the start of good news about the discovery and widespread use of the vaccine.

Table 1 gives the performance of the MSCI factor indexes during the different stages of the Covid-19 crisis. Performance is measured by the return computed on the time-period of each stage, and then annualized for comparison across the different stages. We use data are from Thomson Reuters.

Table 1. Performance of the MSCI factor indexes during the Covid-19 crisis.

Source: computation by the author. Data source: Thomson Reuters.

According to an examination of more than one year worth of market data, the size factor underperformed throughout the study period, most notably during the period of economic stress in the financial markets caused by the Covid-19 crisis. Given the crisis’s unprecedented severity, lockdown essentially shut down small and medium-sized firms, which finally suffered a period of catastrophic financial hardship, culminating in a non-negligible number of chain bankruptcies in the hardest-hit industries. This may help to explain why the Fever phase is the lowest-returning for the size factor. As the crisis progressed and governments spent billions on an accommodating monetary strategy to stimulate demand and re-establish healthy growth, size outperformed in the time after the pandemic’s fever phase (Figure 3).

ETFs to capture the Size factor

Let us recall that an Exchange-Traded Fund (ETF) is an investment vehicle that seeks to mirror the performance of a benchmark like an equity index and is traded on a continuous basis during the day like stocks. By investing in ETFs, an investor gains access to a plethora of diversification options through several asset classes (equity, bonds, currency, commodity, real estate, etc.).

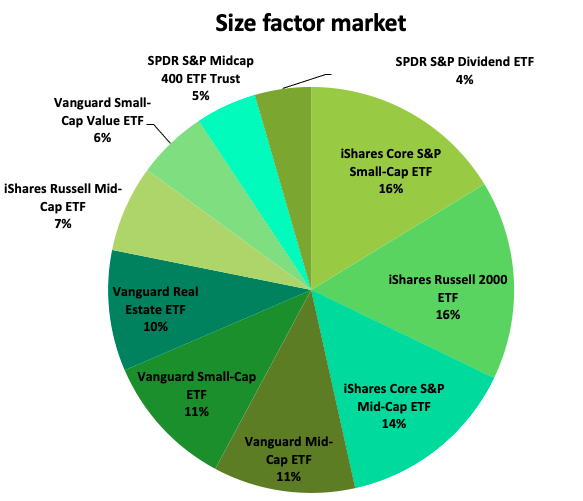

Figure 3 illustrates the overall ETF distribution of the major providers of size factor ETFs in terms of percentage of asset under management. By examining the market overview for size factor investments, we can observe Blackrock and Vanguard dominance in this factor investing market, with 53.40% and 37.27% respectively, representing 90.67% of the overall size factor ETF market.

Figure 3. Size factor ETF market.

Source: etf.com (2021).

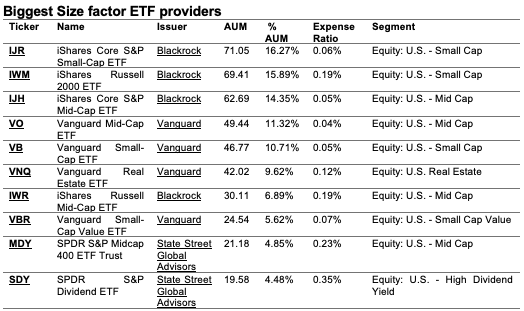

Table 2 gives more detailed information about the biggest size factor ETF providers: the asset under management (AUM), expense ratio (ER) and the segment for the investments.

Table 2. Ranking of the biggest Size ETF providers.

Source: etf.com (2021).

Why should I be interested in this post?

If you are an undergraduate or graduate student in a business school or at the university, you may have seen in your 101 finance course the CAPM related to the market factor. This post makes aware of the existence of another risk factor priced by the market.

If you are an investor, you may consider adding an exposure to size factor to enhance the overall portfolio return.

Related posts on the SimTrade blog

▶ Youssef LOURAOUI Minimum Volatility

▶ Youssef LOURAOUI Value Factor

▶ Youssef LOURAOUI Yield Factor

▶ Youssef LOURAOUI Momentum Factor

▶ Youssef LOURAOUI Quality Factor

▶ Youssef LOURAOUI Growth Factor

Useful resources

Academic research

Banz, R.W., 1981. The relationship between return and market value of common stocks. Journal of Financial Economics, 9: 3-18.

Basu, S., 1977. Investment performance of common stocks in relation to their price-earnings ratios: A test of Efficient Market Hypothesis. The Journal of Finance, 32: 663-682.

Fama, E.F., French, K.R. 1992. The Cross-Section of Expected Stock Returns. The Journal of Finance, 47: 427-465.

Fama, E.F., French, K.R., 2015. A five-factor asset pricing model. Journal of Financial Economics, 116(1): 1-22.

Hasaj, M., Sherer, B., 2021. Covid-19 and Smart-Beta: A Case Study on the Role of Sectors. EDHEC-Risk Institute Working paper.

Litzenberger, R., Ramaswamy, K., 1982. The Effects of Dividends on Common Stock Prices Tax Effects or Information Effects? The Journal of Finance, 37(2): 429-443.

Mangram, M.E., 2013. A simplified perspective of the Markowitz Portfolio Theory. Global Journal of Business Research, 7(1): 59-70.

Pagano, M., Wagner, C., Zechner, J., 2020. Disaster Resilience and Asset Prices, Working paper.

Reinganum, M., 1981. The Arbitrage Pricing Theory: Some Empirical Results. The Journal of Finance, 36(2): 313-321.

Business analysis

etf.com, 2021. Biggest Size Factor ETF providers.

MSCI Investment Research, 2021. Factor Focus: Size.

About the author

The article was written in September 2021 by Youssef LOURAOUI (ESSEC Business School, Global Bachelor of Business Administration, 2017-2021).

9 thoughts on “Size Factor”

Comments are closed.