In this article, Mathilde JANIK (ESSEC Business School, Global Bachelor in Business Administration (GBBA), 2021-2025) comments on two quotes that bridge the gap between financial philosophy and personal development: one from the world’s most successful investor, Warren Buffett, and another from the self-help pioneer, Napoleon Hill. These quotes collectively highlight the profound truth that success in finance, much like success in life, is less about quick wins and more about the quality of the long-term compounding investments we make in businesses and ourselves.

About the Quoted Authors

This post draws on the wisdom of two influential figures: Warren Buffett, the chairman and CEO of Berkshire Hathaway, widely regarded as one of the most successful investors in history and the architect of the Value Investing philosophy; and Napoleon Hill (1883–1970), the American author of the classic 1937 self-help book Think and Grow Rich, whose work focused on the power of belief and consistent, long-term personal discipline.

The selection of these two quotes is deliberate: the first establishes the principle of quality over price in capital allocation (finance), while the second extends this exact same principle to the allocation of time and effort in personal life (self-growth). Together, they form a complete roadmap for achieving sustainable success, reminding us that both financial and personal wealth are built patiently through consistent, high-quality choices.

Quotes

The quote by Warren Buffett

“It’s far better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price than a fair company at a wonderful price.” – Warren Buffett

The quote by Napoleon Hill

“Tell me how you use your spare time, and how you spend your money, and I will tell you where and what you will be in ten years from now.” – Napoleon Hill

Analysis of the quotes

The first quote, from Warren Buffett, is the cornerstone of Value Investing. It focuses on the financial market and how to choose a company to invest in. It makes a lot of sense to always take into account not only the stock price of the company but also everything that goes beyond its market capitalization. Factors like the management and leadership within the company, the cash flows (and their robustness and stability), and the market share compared to competitors are really important. Investing in a robust company that does good things every day may be more profitable than investing in a company that may be cheaper and more appealing for one specific innovation but may not be profitable at all.

This is why I also wanted to include the second quote, which applies the same long-term quality principle to personal development. I came across this quote shortly after reading the book “Think and Grow Rich” by Napoleon Hill, an American author widely known for his self-help books, first published in 1937. He asserted that desire, faith, and persistence can propel one to great heights if one can suppress negative thoughts and focus on long-term goals. I like this quote because it shows that, depending on what we focus on, we can become anything we want. It also shows that it’s about the little things you do every day that will bring you where you want to be in life. I appreciate how this quote shows that spending money is not a deliberate act and we should think this through, questioning ourselves on our own goals and how making specific spending decisions may or may not bring us towards them and what our future self would think of our present decision.

Financial concepts related to the quotes

We can relate these quotes to three core concepts that govern both capital and personal allocation: intrinsic value vs. market price, economic moats and competitive advantage, and the power of compounding.

Intrinsic value vs. Market price

Buffett’s quote directly addresses the difference between a stock’s intrinsic value (the true, underlying economic worth of a business, determined by its future cash flows and qualitative factors like management quality and competitive advantage) and its volatile market price (the price at which it trades publicly). He emphasizes that while price is what you pay, value is what you get. A “wonderful company” has a high intrinsic value, meaning its quality justifies the price, whereas a “fair company” may trade at a low price, but its lack of quality means that price is likely justified by its poor prospects.

Economic moats and competitive advantage

The concept of a “wonderful company” is often defined by its economic moat: a structural feature that protects a company’s long-term profits and market share from competition. Taken from moats that protect castles, certain advantages help protect companies from their competitors. Moats can come from high switching costs for customers, network effects, or intangible assets like brand strength (e.g., Coca-Cola). A company with a strong moat has robust and stable cash flows, which, as I noted, are crucial. Hill’s quote is a mirror: investing in personal skills and knowledge creates a personal “moat” around your career and future earning potential.

The power of compounding

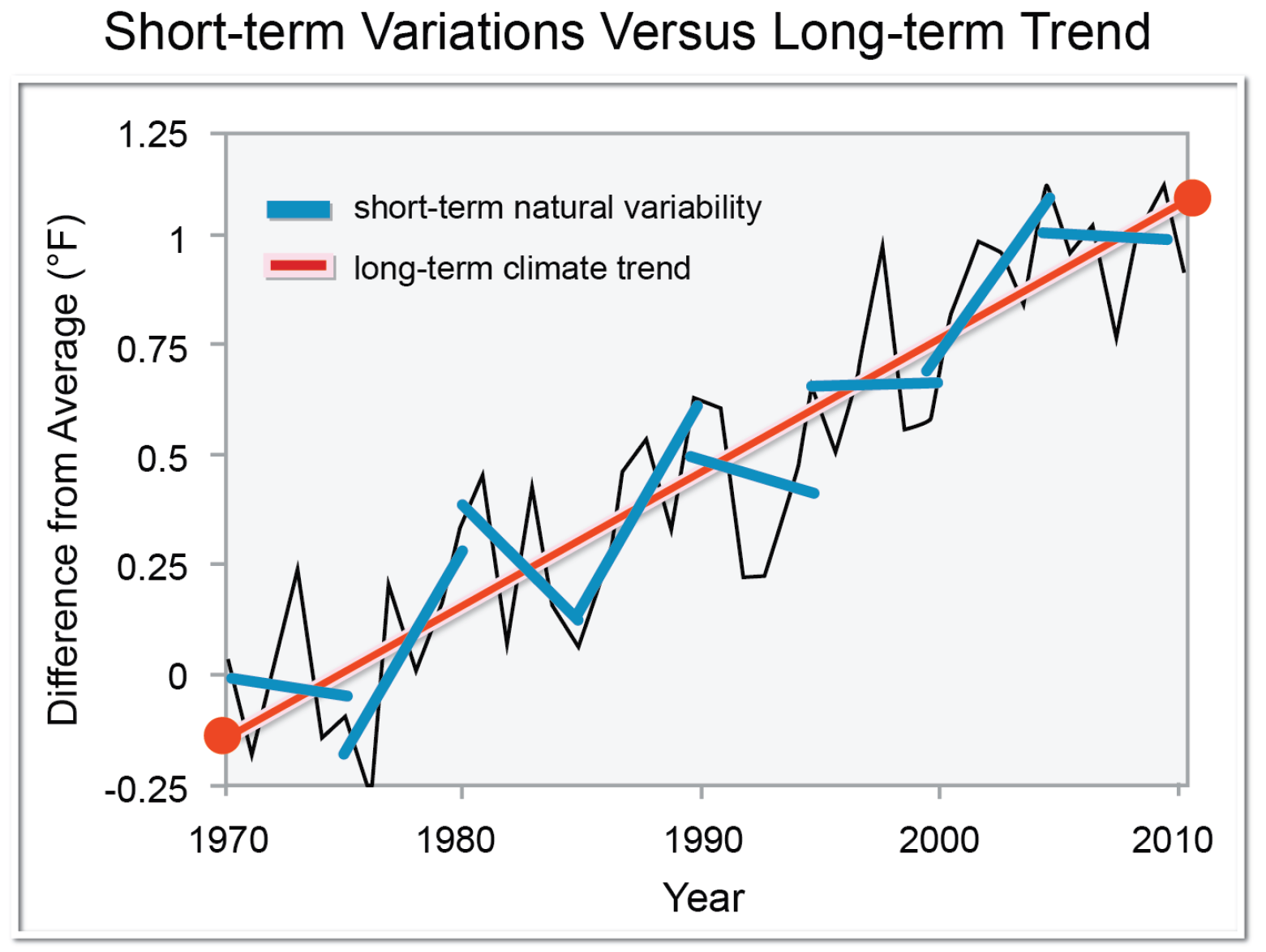

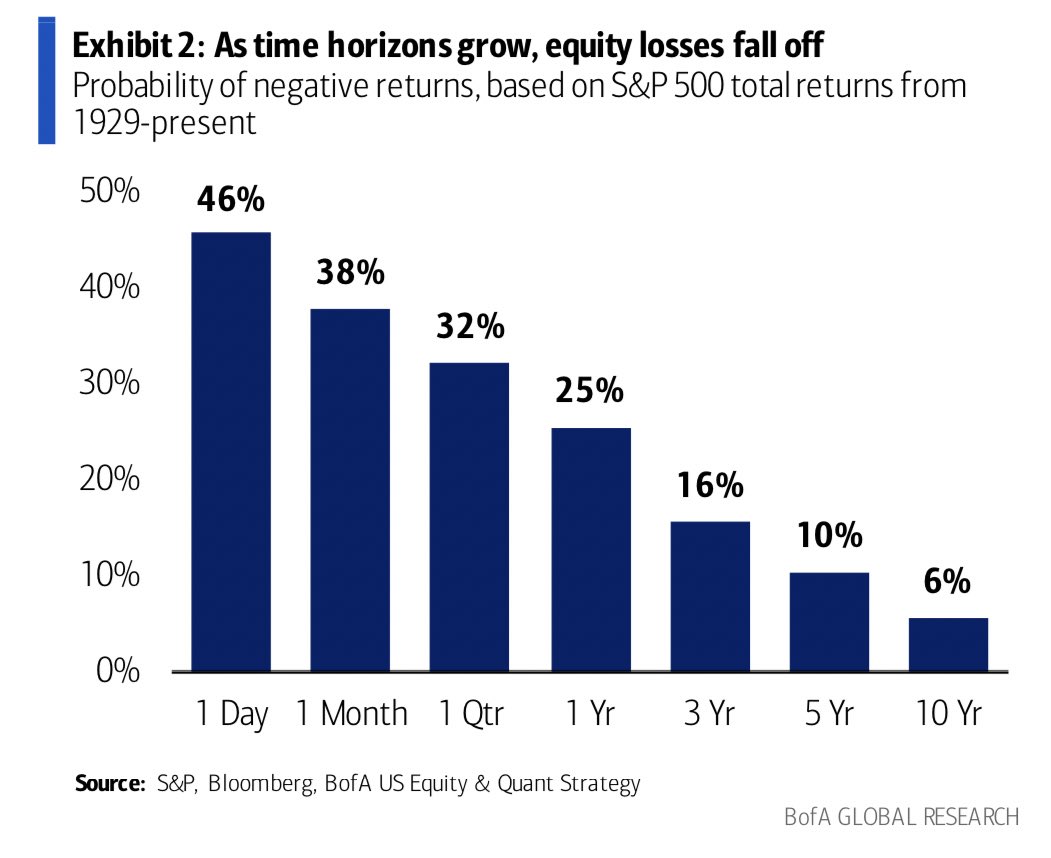

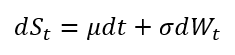

Both quotes relates to the principle of compounding. In finance, it’s the ability of an asset to generate earnings that are then reinvested to generate their own earnings. Buffett seeks companies that compound capital effectively over decades. Napoleon Hill’s quote speaks to compounding in personal life: the cumulative effect of small, positive daily actions (how you use your spare time and spending decisions) that, over ten years, leads to exponential growth in skills, wealth, and character. This continuous, patient investment, whether in a stock or a skill, is the ultimate driver of long-term success. Other authors, such as the best-selling author James Clear in his widely known self-help book Atomic Habits, also present this idea of compounding specifically for everyday skills.

My opinion about this quote

I chose these two quotes because they provide a complete roadmap for success. The Buffett quote provides the external strategy: be disciplined, patient, and focus on quality when allocating capital. The Hill quote provides the internal strategy: be disciplined, patient, and focus on quality when allocating time and effort. As a student of finance, it’s easy to get fixated on technical analysis and short-term movements, but these quotes remind us that the biggest returns come from long-term vision and consistent commitment to fundamental excellence, whether we’re analyzing a company’s leadership or assessing our own daily habits. This dual focus is the best preparation for a successful career in finance and beyond, emphasizing that personal growth and investment success are deeply intertwined.

Why should I be interested in this post?

If you’re a student interested in business and finance, this post is essential. It moves beyond the mechanics of valuation to address the philosophy of investment, a core requirement for success in roles like asset management, portfolio management, and private equity. Understanding Buffett’s principle demonstrates a mature, long-term mindset often tested in interviews. Furthermore, Napoleon Hill’s insight offers a blueprint for personal development, showing that the same consistency and discipline required to choose a “wonderful company” are needed to build a successful professional self through thoughtful allocation of your time and money.

Related posts on the SimTrade blog

Quotes

▶ Hadrien PUCHE “Price is what you pay, value is what you get“ – Warren Buffett

▶ Federico DE ROSSI The Power of Patience: Warren Buffett’s Advice on Investing in the Stock Market

▶ Hadrien PUCHE “The big money is not in the buying and selling, but in the waiting.” – Charlie Munger

Financial techniques

▶ All posts about Financial Techniques

▶ Andrea ALOSCARI Valuation methods

▶ Maite CARNICERO MARTINEZ How to compute the net present value of an investment in Excel

Useful resources

Cunningham, L.A (1997) The Essays of Warren Buffett: Lessons for Corporate America, Fourth Edition.

Hill, N. (1937). Think and Grow Rich. New York: The Ralston Society.

Graham, B., & Dodd, D. L. (1934). Security Analysis. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Autorité des Marchés Financiers (AMF) Guide d’élaboration des prospectus et de l’information à fournir en cas d’offre au public ou d’admission de titres financiers

Autorité des Marchés Financiers (AMF) (January 2026) Les obligations d’information des sociétés cotées

Autorité des Marchés Financiers (AMF) Guides épargnants

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Resources for Investors

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Beginners Guide to Investing

About the author

The article was written in January 2026 by Mathilde JANIK (ESSEC Business School, Global Bachelor in Business Administration (GBBA), 2021-2025).

▶ Discover all articles written by Mathilde JANIK.