My experience at the startup BSD Investing

In this article, Rohit SALUNKE (ESSEC Business School, Grande Ecole Program – Master in Management, 2018-2021) shares his experience working in a startup and the evolution of his role and responsibilities…

About BSD Investing

BSD Investing is an independent research firm operating in the asset management industry. It primarily provides research and analysis on active vs passive fund performances for equity and debt funds present across the global financial markets.

The funds are domiciled in Europe (i.e., these are European funds investing in domestic and international markets) and span across 62 universes (i.e., global markets and investment styles).

The goal of the research is to provide BSD Investing clients with insights into the active vs passive performances and help them optimize the portfolio to get better risk adjusted returns.

The evolution of my missions

I started working at this startup in July 2019 in a small office in Saint-Lazare area in Paris, France. At the beginning, it was just me and two others, the founder, and her colleague. We started from scratch, trying to figure out the best data source to use, figuring out the process flow, the product and much more. After selecting Morningstar as our primary data provider, I began writing codes in Python to fetch the data, create our own portfolios and develop performance key performance indicators (KPIs) for those portfolios. Since we did not have any employee skilled in IT, I was the one who took charge of creating the entire IT architecture from data handling to reporting.

After working for about eight months, we hired our head of IT, and he took over the handling of the IT system and made it much more efficient. That’s when I got the chance to devote my entire focus in developing quantitative models and simulations for the performances of our portfolios.

I started off with researching various technical indicators that gave insights into the market performances and how active funds fared in comparison to passive funds. A major portion of my time was devoted to simulating portfolio performances using various indicator signals. The signals were basically an indication to increase or decrease the active allocation to the portfolio.

Apart from this, I helped a lot with creating marketing materials, conducting market research, interviewing portfolio managers to understand the asset management industry and their needs.

In addition, I work very closely with the IT head to implement our models and key indicators onto the website.

Active and Passive funds

The asset management industry is broadly divided into two management styles: the active style and the passive style. Both styles follow a benchmark that could be an index (e.g., CAC 40), or a combination of indices, or a new portfolio that represent the entire universe of financial instruments in the category that the manager wants to invest in (e.g., Emerging countries large cap ESG funds).

Passive style

The goal of the passive fund manager is to create a portfolio that tracks closely the chosen benchmark. But, since a benchmark consists of a large number of stocks, investing in all of them is not very feasible or cost effective. Therefore, the passive manager creates a portfolio using a smaller number of instruments that aims to replicate the returns from the benchmark.

A good metric to measure the performance of a passive fund is tracking error. It is the divergence between the fund returns and those of the benchmark. A low tracking error means that the fund is tracking the benchmark closely and thus is performing well. Since, a passive fund (also known as ETF or index fund) manager does not aim to outperform the benchmark, but just to simply replicate its returns. Therefore, passive funds charge low fees.

Active style

An active manager on the other hand aims to beat the funds benchmark through stock picking, sector rotation and/or other methods. He or she thus takes a larger risk than a passive fund manager and needs a lot more research, expertise, and management. Therefore, an active fund generally charges more fees than a passive fund. For example, among the France large cap funds, an average passive fund charges around 0.25% of fees, whereas an active manager’s fee may range from 1-2%, in some cases more than 4%.

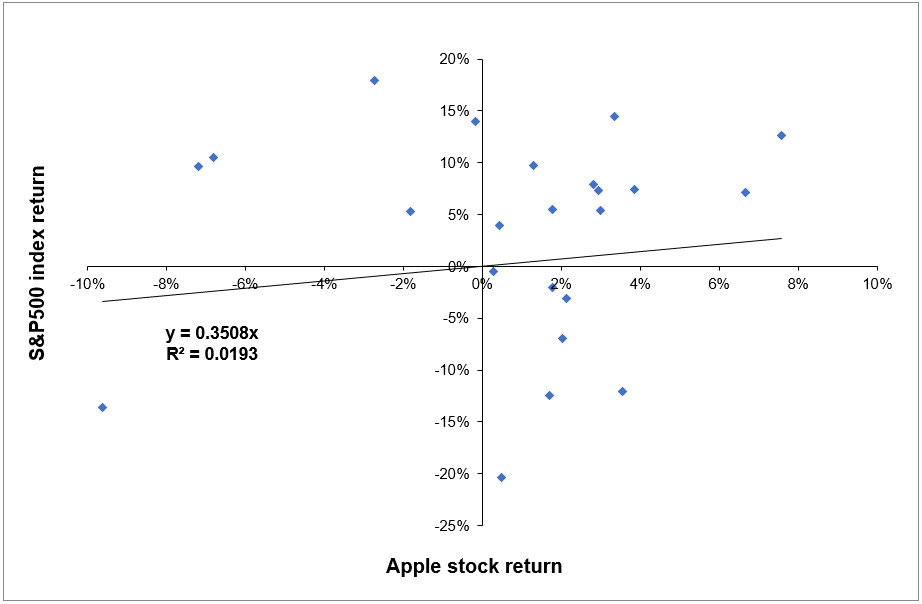

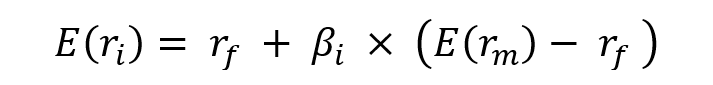

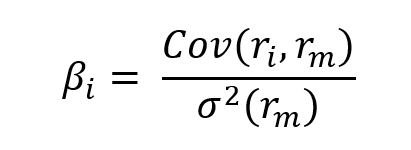

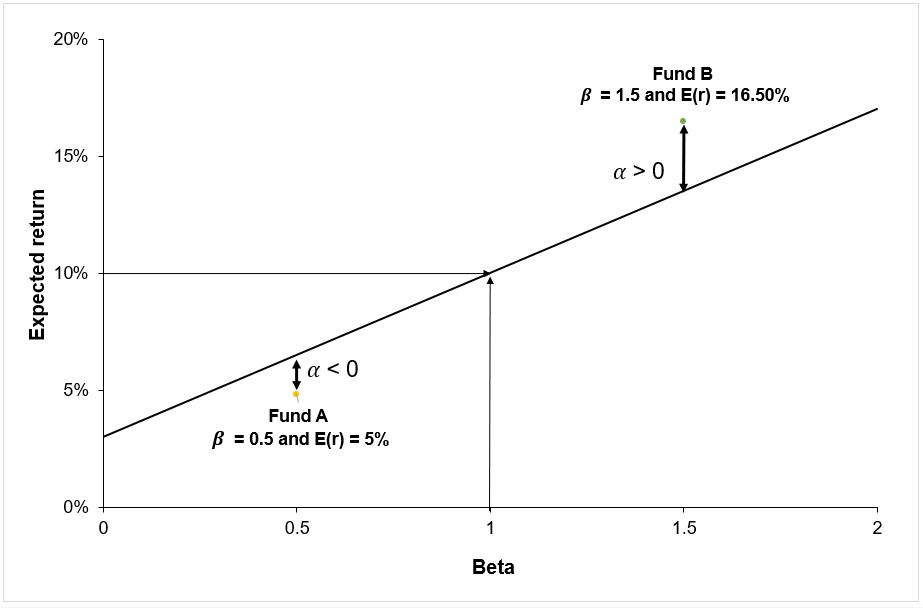

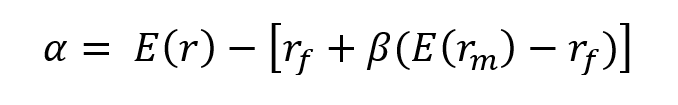

Active managers are alpha seeking. Alpha is the excess return that an active manager generates compared to its benchmark. There are multiple ways to calculate alpha. One such way is using the CAPM model. We predict the expected return of the portfolio using the CAPM model. Subtracting this return from the active managers portfolio gives the alpha. A passive funds alpha is supposed to be zero.

Fund of funds managers create a portfolio of active and/or passive funds to meet their return and risk objectives.

Best style?

In the asset management industry, there is an ongoing debate about which management style is better and are the extra fees charged by the active managers really worth it?

In the US, for example, the active funds have performed very poorly as compared to the ETFs. Whereas, in Europe the performance was mixed and in Japan, the active funds performed better. However, these are the results over the entire period of 10 years. There have been many periods when the active funds outperformed.

Taking the recent example, after the Covid-19 pandemic, the markets went haywire. Since then, in most of the universes active funds have outperformed the passive funds. Therefore, higher returns can be achieved by understanding the markets and allocating the portfolio to the right management style at the right time.

My key learnings

Working in a startup is always challenging and the job comes with heavy responsibilities.

And although working in a startup sounds very interesting, most of the work during the very beginning is quite tedious when it comes to data handling. I spent a few months just understanding the data, checking for errors from the source, figuring out ways to deal with data errors and so on.

Once, I started working on the quantitative models and the simulations, I felt that my work has just begun. During this time, I learnt a big lesson regarding building quantitative models. I build very sophisticated models including machine learning models such as neural networks, gradient boosted trees and so on. However, despite the good results, I had to use simpler logistic models because selling overly sophisticated models would become very difficult.

People in the asset management industry need to know what the real meaning of the data is. And giving recommendations using a black box model does not make it very easy to understand the functioning of the model.

Working on the various indicators, trying to understand their correlations with active and passive fund performances gave me good insights about them. For instance, one good variable that works the best for me is dispersion. This is the standard deviation of returns among funds or stocks. During periods of high dispersion, I observed that active funds generally outperformed the passive funds. I saw a similar result during periods of high volatility. An explanation to this is that a high dispersion could signify a period of high inefficiency in the market, which the active managers could take advantage of. When markets are highly efficient, it makes sense to invest in ETFs, and reduce your costs. Whereas, during periods of high inefficiency, a good active manager could be worth the higher fees that he/she charges. As described above, since March 2019, the active managers have generally outperformed the passive funds across many universes. And this period is also marked with high dispersion and volatility.

In addition, we found that bear periods were more conducive to active outperformance, while bull periods were not. This can be understood since the volatility and dispersion is generally high during bear periods. However, periods after March 2019 were an anomaly to this, since although the markets are in a bull run, there is high dispersion and volatility, and the active funds are outperforming the ETFs.

Knowledge and skills required

For this job I had to have strong data skills, coding skills as well as sound knowledge about finance.

In addition, since I had little to no guidance in my role, I had to come up with my own tasks, define the product and its objects and then learn the essential skills to build it.

Therefore, there was a lot of market research, visits to stackoverflow, reading research papers, cold mailing portfolio managers and so on. Thus, project management and communication skills are essential.

Hard Skills

- Python

- SQL

- HTML

- MorningstarDirect

- Capital Markets

- Portfolio Management, Optimization …

- Risk Management

- Market Research

Soft Skills

- Communication

- Project Management

- Leadership

- Entrepreneurial Thinking

- Ability to handle pressure

- Dedication to your project and display of ownership

Related posts on the SimTrade blog

▶ All posts about Professional experiences

▶ Youssef LOURAOUI Passive Investing

▶ Youssef LOURAOUI Active Investing

Useful resources

About the author

The article was written in December 2021 by Rohit SALUNKE (ESSEC Business School, Grande Ecole Program – Master in Management, 2018-2021).