In this article, Emanuele BAROLI (MiF 2025–2027, ESSEC Business School) examines how shifts in interest rates shape the M&A market, outlining how deal structures differ when central banks raise versus cut rates.

Context and objective

The purpose is to explain what interest rates are, how they interact with inflation and liquidity, and how these variables shape merger and acquisition (M&A) activity. The intended outcome is an operational lens you can use to read the current monetary cycle and translate it into cost of capital, valuation, financing structure, and execution windows for deals, distinguishing—when useful—between corporate acquirers and private-equity sponsors.

What are interest rates

Interest rates are the intertemporal price of funds. In economic terms they remunerate the deferral of consumption, insure against expected inflation, and compensate for risk. For real decisions the relevant object is the real rate because it governs the trade-off between investing or consuming today versus tomorrow.

Central banks anchor the very short end through the policy rate and the management of system liquidity (reserve remuneration, market operations, balance-sheet policies). Markets then map those signals into the entire yield curve via expectations about future policy settings and required term premia. When liquidity is ample and cheap, risk-free yields and credit spreads tend to compress; when liquidity becomes scarcer or dearer, yields and spreads widen even without a headline change in the policy rate. This transmission, with its usual lags, is the bridge from monetary conditions to firms’ investment choices.

M&A industry — a definition

The M&A industry comprises mergers and acquisitions undertaken by strategic (corporate) acquirers and by financial sponsors. Activity is the joint outcome of several blocks: the cost and elasticity of capital (both debt and equity), expectations about sectoral cash flows, absolute and relative valuations for public and private assets, regulatory and antitrust constraints, and the degree of managerial confidence. Interest rates sit at the center because they enter the denominator of valuation models—through the discount rate—and they shape bankability constraints through the debt service burden. In other words, rates influence both the price a buyer can rationally pay and the feasibility of financing that price.

Use of leverage

Leverage translates a given cash-flow profile into equity returns. In leveraged acquisitions—especially LBOs—the all-in cost of debt is set by a market benchmark (in practice, Term SOFR at three or six months in the U.S., and Euribor in the euro area) plus a spread reflecting credit risk, liquidity, seniority, and the supply–demand balance across channels such as term loans, high-yield bonds, and private credit. That all-in cost determines sustainable leverage, shapes covenant design, and fixes the headroom on metrics like interest coverage and net leverage. It ultimately caps the bid a sponsor can submit while still meeting target returns. Corporate acquirers usually employ more modest leverage, yet remain rate-sensitive because medium-to-long risk-free yields and investment-grade spreads feed both fixed-rate borrowing costs and the WACC used in DCF and accretion tests, and they influence the value of stock consideration in mixed or stock-for-stock deals.

How interest rates impact the M&A industry

The connection from rates to M&A operates through three main channels. The first is valuation: holding cash flows constant, a higher risk-free rate or higher term premia lifts discount rates, lowers present values, and compresses multiples, thereby narrowing the economic room to pay a control premium. The second is bankability: higher benchmarks and wider spreads raise coupons and interest expense, reduce sustainable leverage, and shrink the set of financeable deals—most visibly for sponsors whose equity returns depend on the spread between debt cost and EBITDA growth. The third is market access: heightened rate volatility and tighter liquidity reduce underwriting depth and risk appetite in loans and bonds, delaying signings or closings; the mirror image under easing—lower rates, stable curves, and tighter spreads—reopens windows, enabling new-money term funding and refinancing of maturities. The net effect is a function of level, slope, and volatility of the curve: lower and calmer curves with steady spreads tend to support volumes; high or unstable curves, even with unchanged spreads, enforce selectivity.

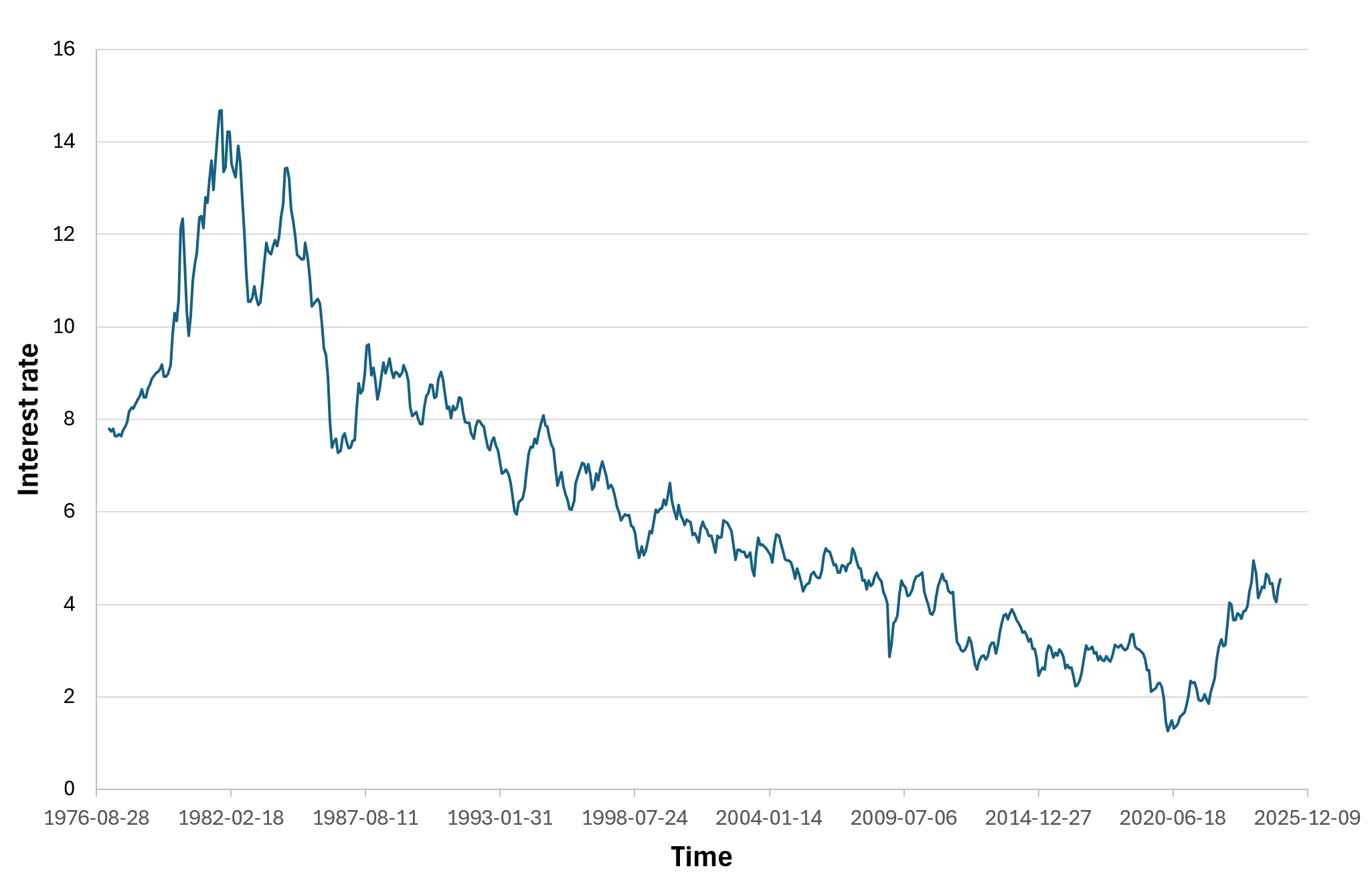

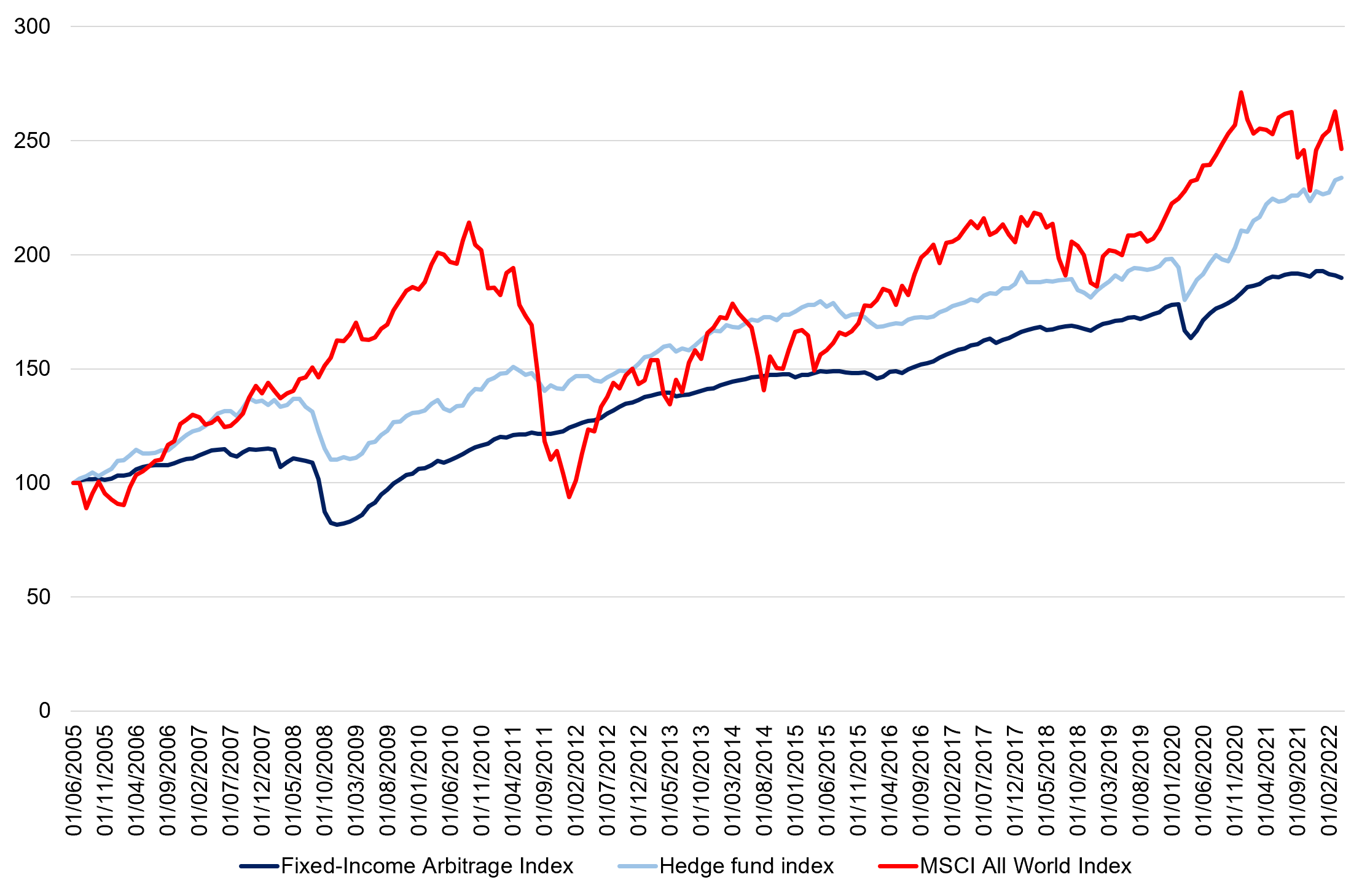

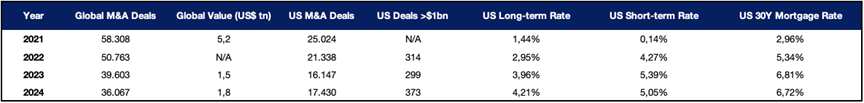

Evidence from 2021–2024 and what the chart shows

M&A deals and interest rates (2021-2024).

Source: Fed.

The global pattern over 2021–2024 is consistent with this mechanism. In 2021, deal counts reached a cyclical peak in an environment of near-zero short-term rates, abundant liquidity, and elevated equity valuations; frictions on the cost of capital were minimal and access to debt markets was easy, so the economic threshold for completing transactions was lower. Between 2022 and 2024, monetary tightening lifted short-term benchmarks rapidly while spreads and uncertainty rose; global deal counts fell materially and the market became more selective, favoring higher-quality assets, resilient sectors, and transactions with stronger industrial logic. Over this period, global deal counts were 58,308 in 2021, 50,763 in 2022, 39,603 in 2023, and 36,067 in 2024, while U.S. short-term rates moved from roughly 0.14% to above 5%; the chart shows an inverse co-movement between the cost of money and activity. Correlation is not causation—antitrust enforcement, energy shocks, equity multiple swings, and the rise of private credit also mattered—but the macro signal aligns with monetary transmission.

What does academic research say

Academic research broadly confirms the mechanism sketched above: when policy rates rise and financing conditions tighten, both the volume and composition of M&A activity change. Using U.S. data, Adra, Barbopoulos, and Saunders (2020) show that increases in the federal funds rate raise expected financing costs, are followed by more negative acquirer announcement returns, and significantly increase the probability that deals are withdrawn, especially when monetary policy uncertainty is high. Fischer and Horn (2023) and Horn (2021) exploit high-frequency monetary-policy shocks and find that a contractionary shock leads to a persistent fall in aggregate deal numbers and values—on the order of 20–30%—with the effect concentrated among financially constrained bidders; at the same time, the average quality of completed deals improves because weaker acquirers are screened out. Work on leveraged buyouts links this to credit conditions: Axelson et al. (2013) document that cheap and abundant credit is associated with higher leverage and higher buyout prices relative to comparable public firms, while theoretical models such as Nicodano (2023) show how optimal LBO leverage and default risk respond systematically to the level of risk-free rates and credit spreads.

Related posts on the SimTrade blog

▶ Bijal GANDHI Interest Rates

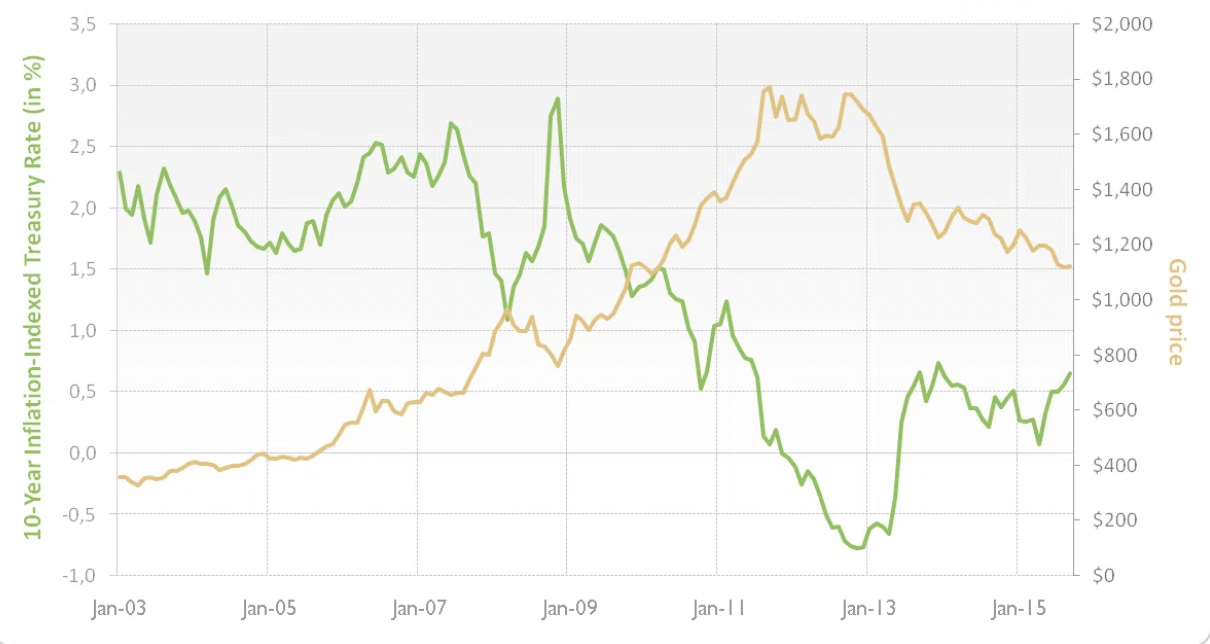

▶ Nithisha CHALLA Relation between gold price and interest rate

▶ Roberto RESTELLI My internship at Valori Asset Management

Useful resources

Academic articles

Adra, S., Barbopoulos, L., & Saunders, A. (2020). The impact of monetary policy on M&A outcomes. Journal of Corporate Finance, 62, 1-61.

Fischer, J. and Horn, C.-W. (2023), Monetary Policy and Mergers and Acquisitions, Working paper Available at SSRN

Horn, C.-W. (2021) Does Monetary Policy Affect Mergers and Acquisitions? Working paper.

Axelson, U., Jenkinson, T., Strömberg, P., & Weisbach, M. S. (2013) Borrow Cheap, Buy High? The Determinants of Leverage and Pricing in Buyouts, The Journal of Finance, 68(6), 2223-2267.

Financial data

Federal Reserve Bank of New York Effective Federal Funds Rate (EFFR): methodology and data

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Effective Federal Funds Rate (FEDFUNDS)

OECD Data Long-term interest rates

About the author

The article was written in November 2025 by Emanuele BAROLI (ESSEC Business School, Master in Finance (MiF), 2025–2027).

▶ Read all articles by Emanuele BAROLI.