In this article, SHIU Lang Chin (ESSEC Business School, Global Bachelor in Business Administration (GBBA), 2024-2026) explains the “lemming effect” in financial markets, inspired by the animated movie Zootopia.

About the concept

The “lemming effect” refers to situations where individuals follow the crowd unthinkingly, just as lemmings are believed to follow one another off a cliff. In finance, this idea is linked to herd behaviour: investors imitate the actions of others instead of relying on their own information or analysis.

The image above is a cartoon showing a line of lemmings running off a cliff, with several already falling through the air. The caption “The Lemming Effect: Stop! There is another way” warns that blindly following others can lead to disaster, even if “everyone is doing it.” The message is to think independently, question group behaviour, and choose an alternative path instead of copying the crowd.

In Zootopia, there is a scene where lemmings dressed as bankers leave their office and are supposed to walk straight home after work. However, after one lemming notices Nick selling popsicles and suddenly changes direction to buy one, the rest of the lemmings automatically follow and queue up too, even though this is completely different from their original route and plan. This illustrates how individuals can abandon their own path and intentions simply because they see someone else acting first, much like investors may follow others into a trade or trend without conducting independent analysis.

Watch the video!

Source: Zootopia (Disney, 2016).

The first image shows Nick Wilde (the fox) holding a red paw-shaped popsicle. In the film, Nick uses this eye‑catching pawpsicle as a marketing tool to attract the lemmings and earn a profit.

Source: Zootopia (Disney, 2016).

The second image shows a group of identical lemmings in suits walking in and out of a building labelled “Lemming Brothers Bank.” This is a parody of the real investment bank “Lehman Brothers,” which collapsed during the 2008 financial crisis. When one lemming notices the pawpsicle, it immediately changes direction from going home and heads toward Nick to buy the product, illustrating how one individual’s choice triggers the rest to follow.

Source: Zootopia (Disney, 2016).

The third image shows Nick successfully selling pawpsicles to a whole line of lemmings. Nick is exploiting the lemmings’ herd‑like behaviour: once a few begin buying, the others automatically copy them and all purchase the same pawpsicle. The humour lies in how Nick profits from their conformity, using their predictable group behaviour—the “lemming effect”—to make easy money.

Source: Zootopia (Disney, 2016).

Behavioural finance uses the lemming effect to describe deviations from perfectly rational decision-making. Rather than analysing fundamentals calmly, investors may be influenced by social proof, fear of missing out (FOMO) or the comfort of doing what “everyone else” seems to be doing.

Understanding the lemming effect is important both for professional investors and students of finance. It helps to explain why markets sometimes move far away from fundamental values and reminds decision-makers to be cautious when “the whole market” points in the same direction.

How the lemming effect appears in markets

In practice, the lemming effect can be seen when large numbers of investors buy the same “hot” stocks simply because prices are rising, they assume that so many others doing the same thing cannot be wrong.

It applies in reverse during market downturns. Bad news, rumours, or sharp price declines can trigger a wave of selling. The fear of being the last one can push them to copy others’ behaviour rather than stick to their original plan.

Such herd-driven moves can amplify volatility, push prices far above or below intrinsic value, and create opportunities or risks that would not exist in a purely rational market. Recognising these dynamics helps investors to step back and question whether they are thinking independently.

Related financial concepts

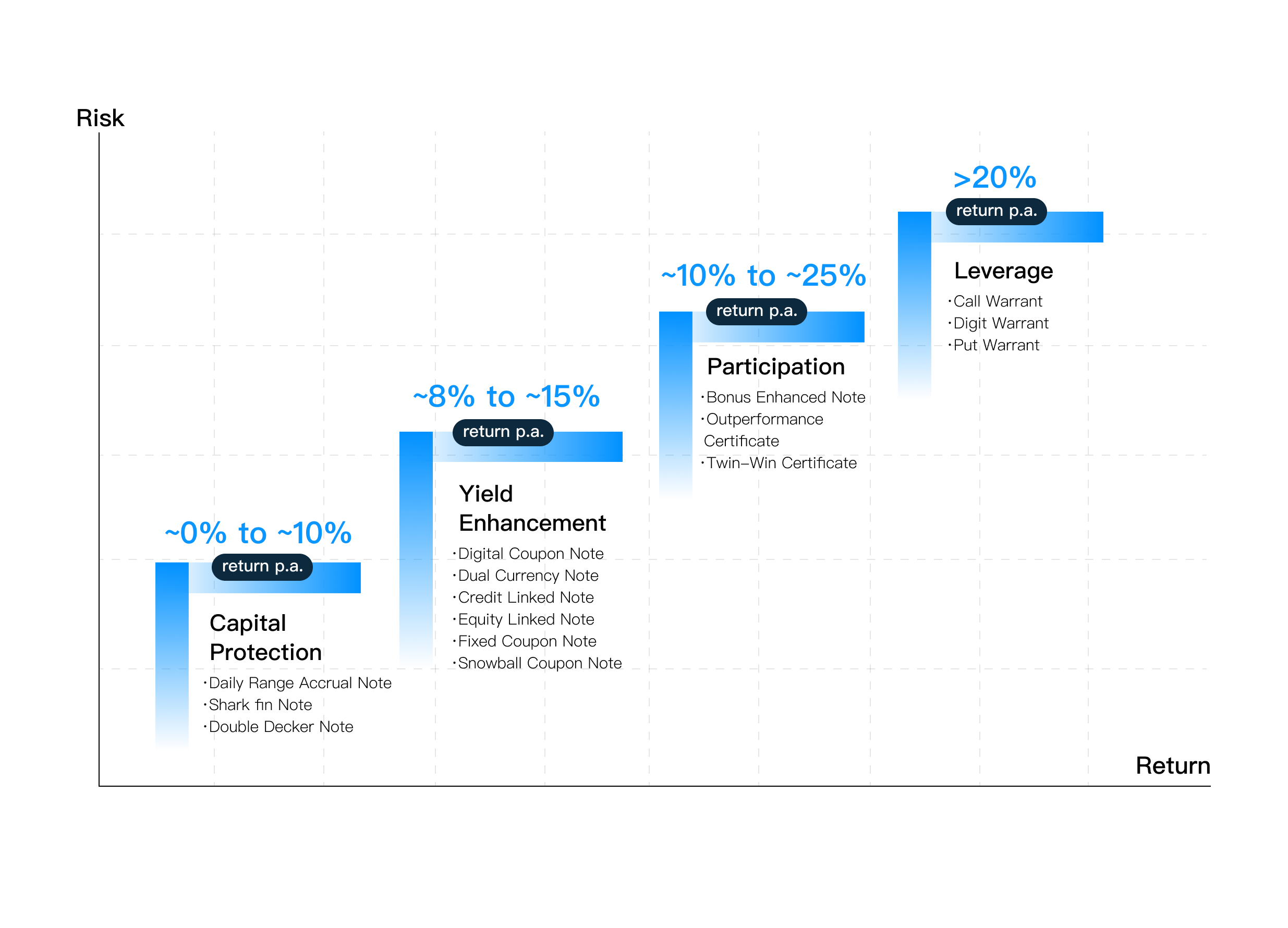

The lemming effect connects naturally with several basic financial ideas: diversification, risk-return trade-off, market efficiency, Keynes’ beauty contest and gamestop story. It shows how human behaviour can distort these textbook concepts in real markets.

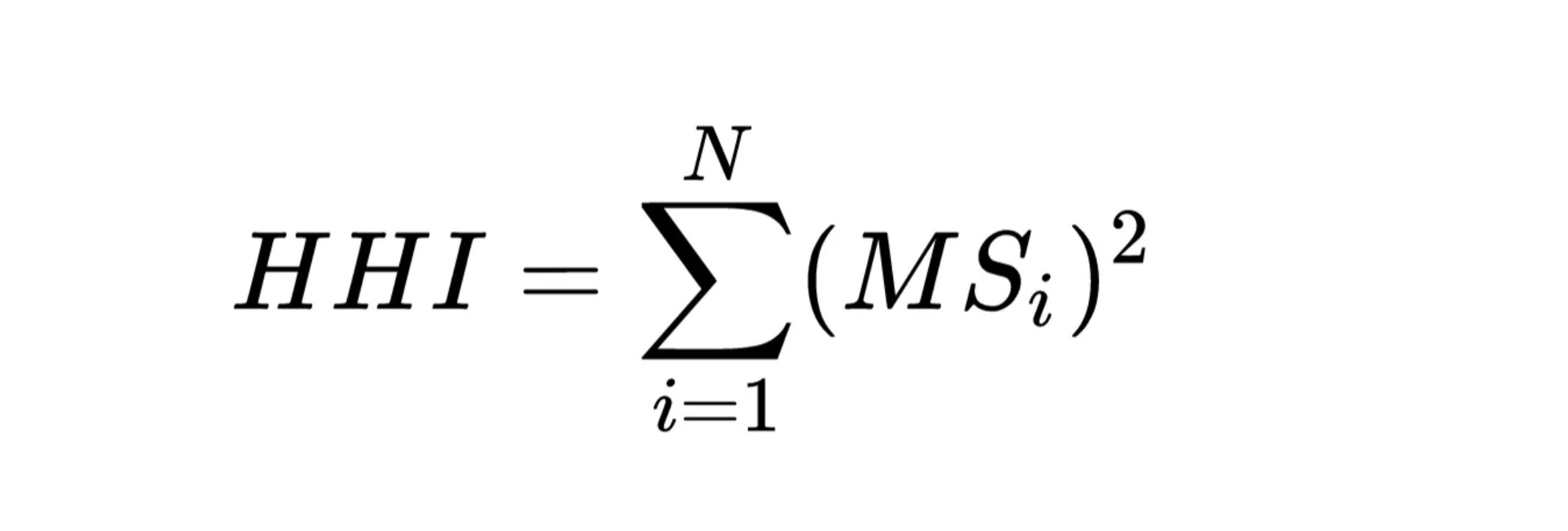

Diversification

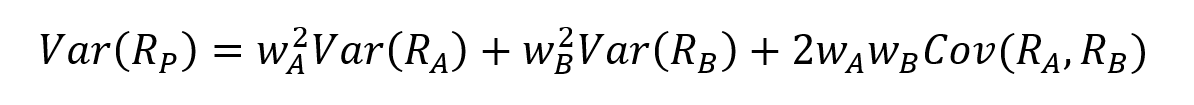

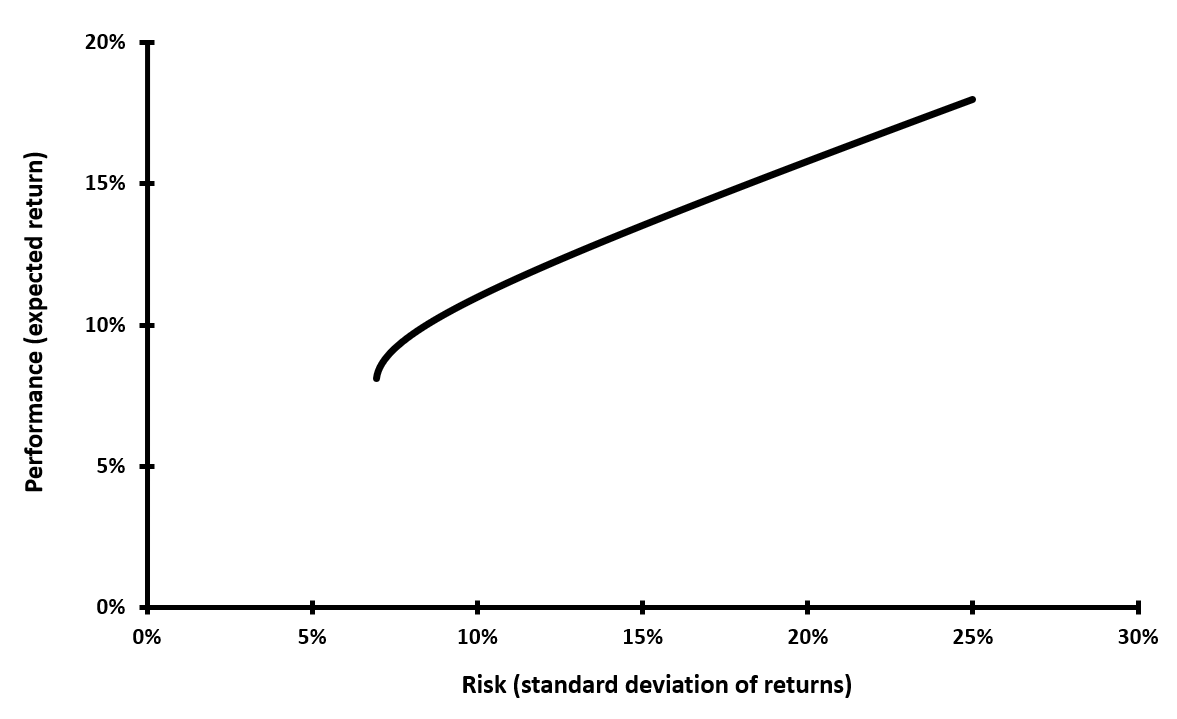

Diversification means not putting all your money in the same blanket (asset or sector), so that the poor performance of one investment does not destroy the whole. When the lemming effect is strong, investors often forget diversification and concentrate on a few “popular” stocks. From a diversification perspective, following the crowd can increase risk without necessarily increasing expected returns.

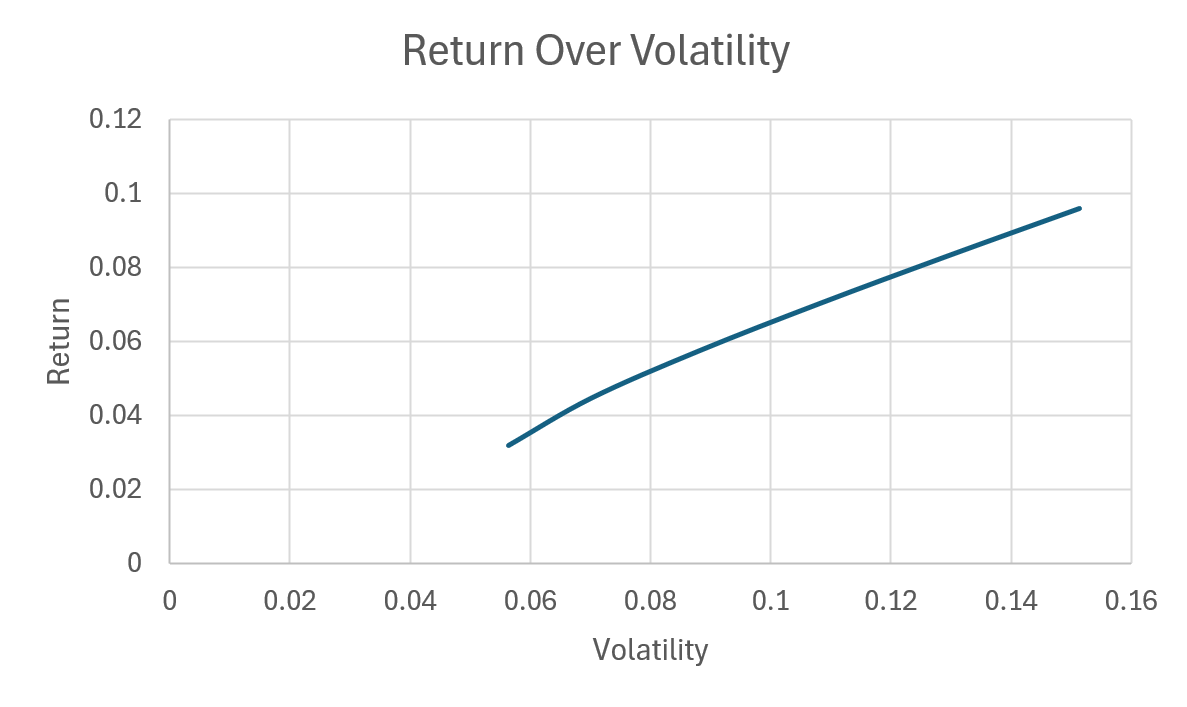

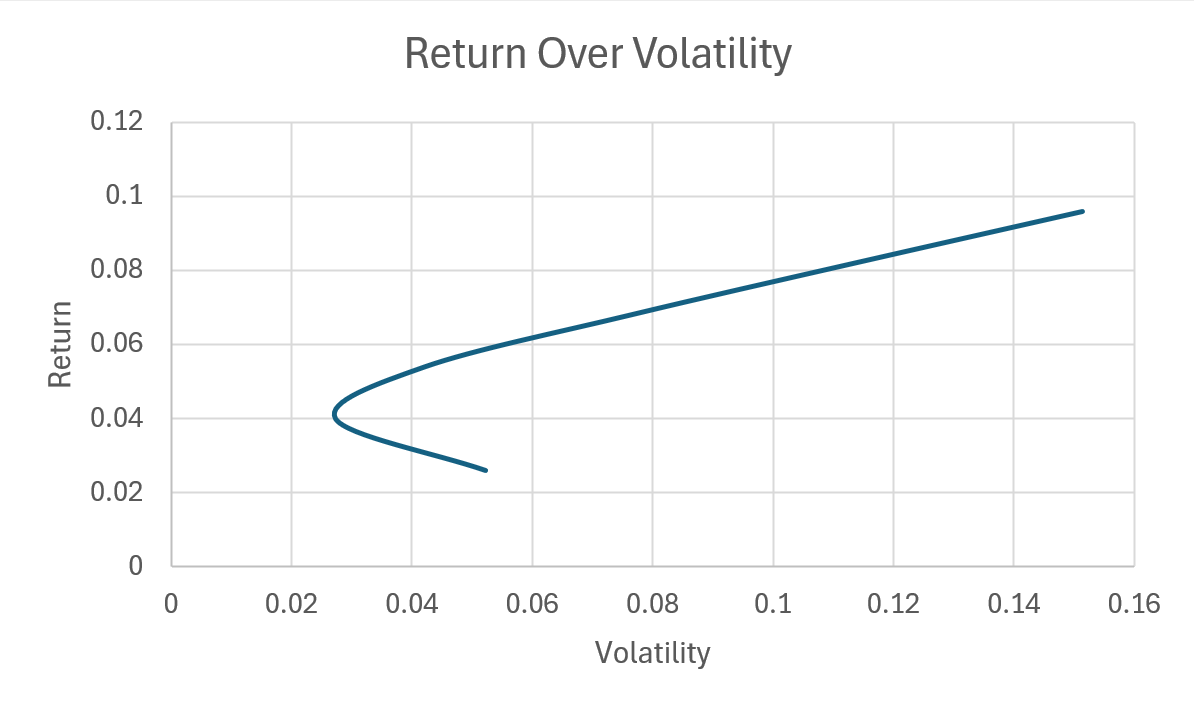

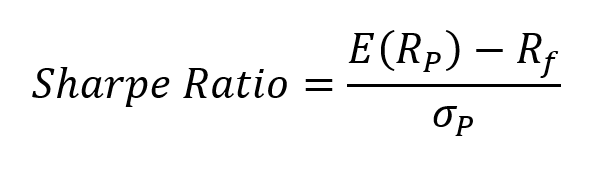

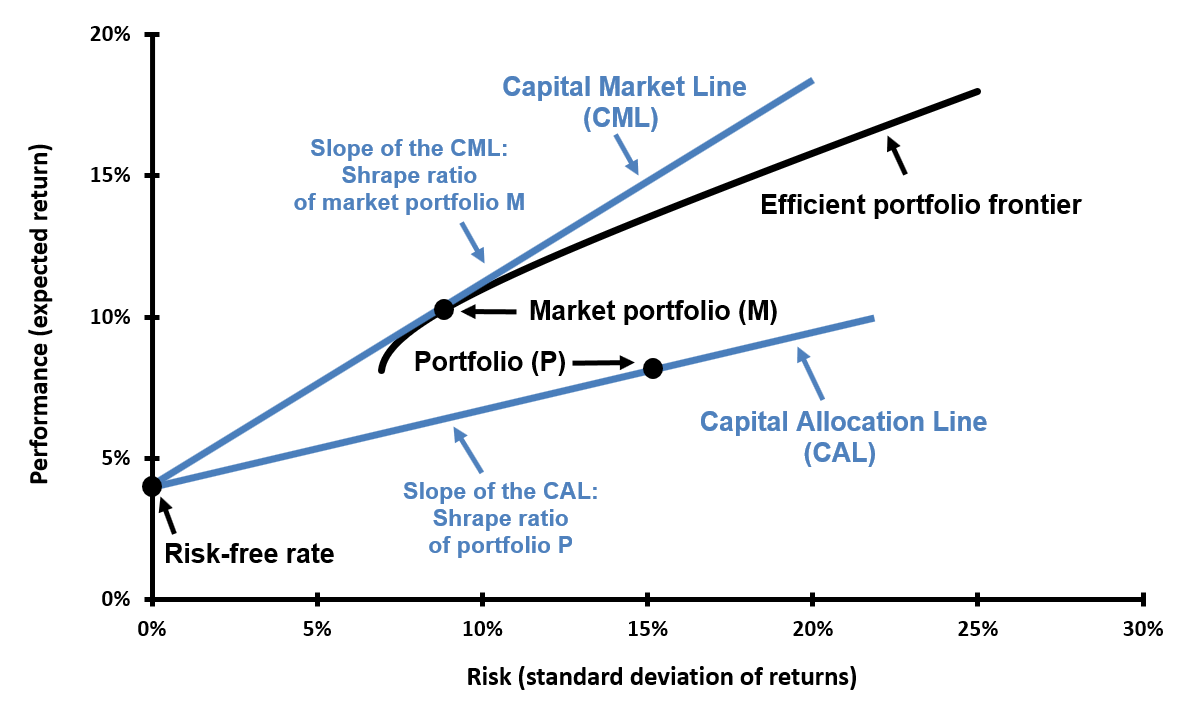

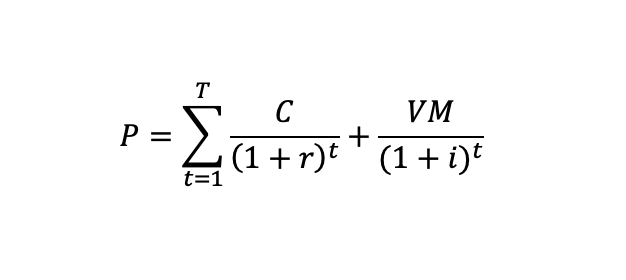

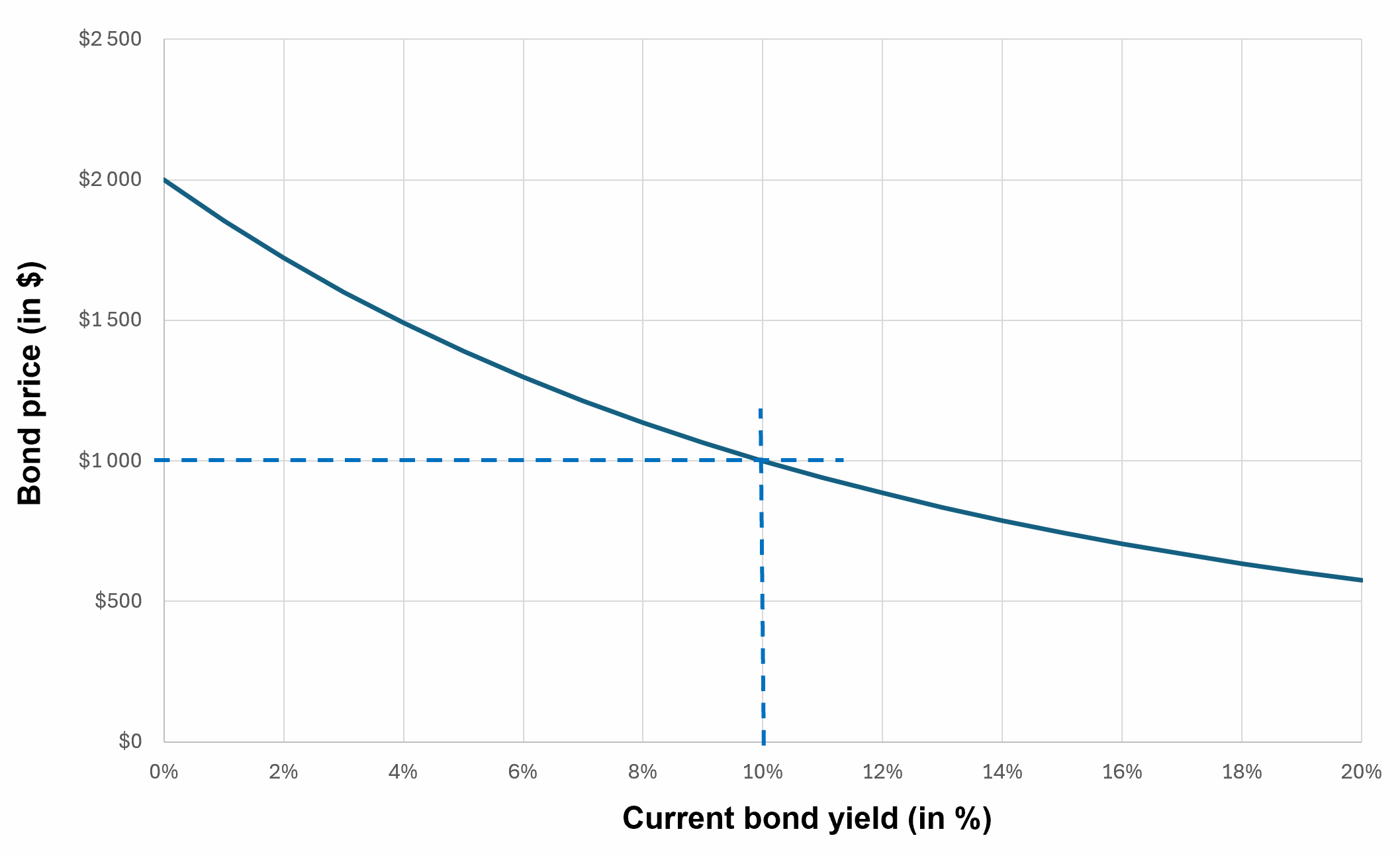

Risk and return

Finance said that higher expected returns usually come with higher risk. However, when many investors behave like lemmings, they may underestimate the true risk of crowded trades. Rising prices can create an illusion of safety, even if fundamentals do not justify the move. Understanding the lemming effect reminds investors to ask whether a sustainable increase in expected return really compensates the extra risk taken by following the crowd.

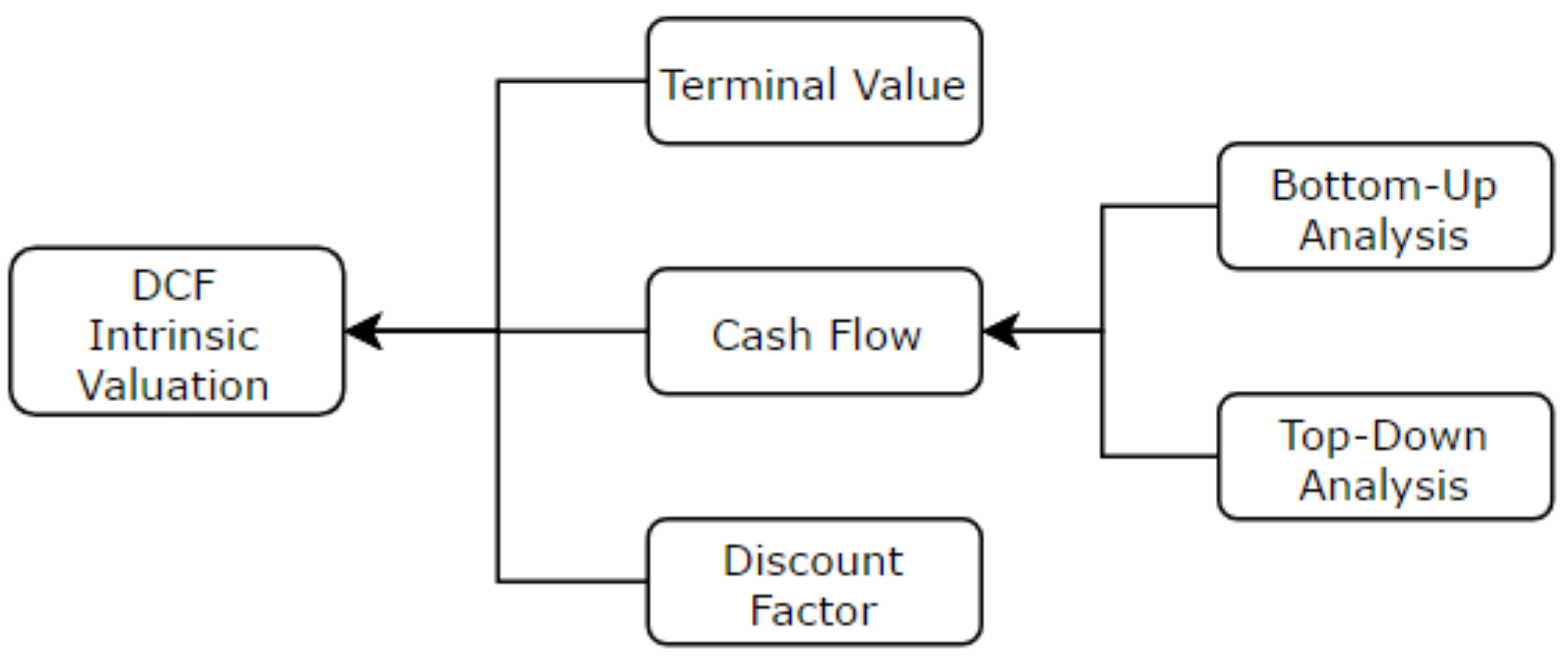

Market efficiency

In an efficient market, prices should reflect all available information. Herd behaviour and the lemming effect demonstrate that markets can deviate from this ideal when many investors react based on emotions or social cues rather than information. Short-term mispricing created by herding can eventually be corrected when new information becomes available or when rational investors intervene. For students, this illustrates why theoretical models of perfect efficiency are useful benchmarks but do not fully capture real-world behaviour.

Keynes’ beauty contest

Keynes’ “beauty contest” analogy describes investors who do not choose stocks based on their own view of fundamental value, but instead try to guess what everyone else will think is beautiful.Instead of asking “Which company is truly best?”, they ask “Which company does the average investor think others will like?” and buy that, hoping to sell to the next person at a higher price. This links directly to the lemming effect: investors watch each other and pile into the same trades, just like the lemmings all changing direction to follow the first one who goes for the pawpsicle.

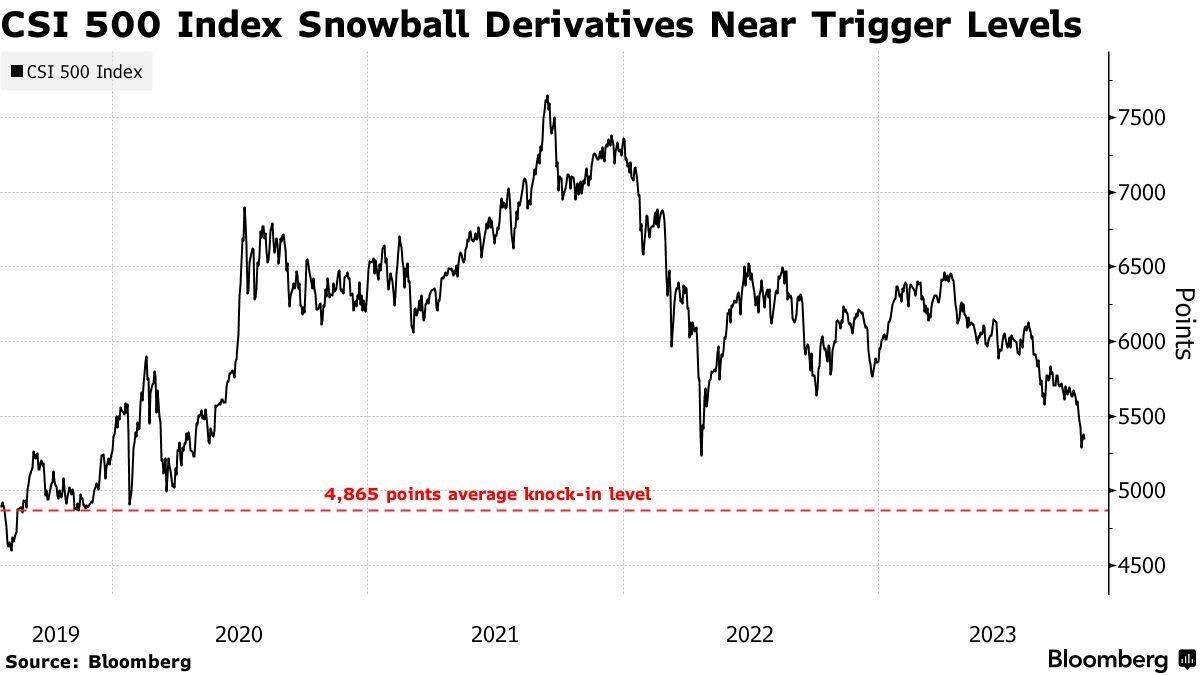

GameStop story

The GameStop short squeeze in 2021 is a modern real‑world illustration of herd behaviour. A large crowd of retail investors on Reddit and other forums started buying GameStop shares together, partly for profit and partly as a social movement against hedge funds, driving the price far above what traditional valuation models would suggest. Once the price started to rise sharply, more and more people jumped in because they saw others making money and feared missing out, reinforcing the crowd dynamic in a very “lemming‑like” way.

Why should I be interested in this post?

For business and finance students, the lemming effect is a bridge between psychology and technical finance. It helps explain why prices sometimes move in surprising ways, and why sticking mindlessly to the crowd can be dangerous for long-term wealth.

Whether you plan to work in banking, asset management, consulting or corporate finance, understanding herd behaviour can improve your judgment. It encourages you to combine quantitative tools with a critical view of market sentiment, so that you do not become the next “lemming” in a crowded trade.

Related posts on the SimTrade blog

▶ All posts about Financial techniques

▶ Hadrien PUCHE “The market is never wrong, only opinions are“ – Jesse Livermore

▶ Daksh GARG Social Trading

▶ Raphaël ROERO DE CORTANZE Gamestop: how a group of nostalgic nerds overturned a short-selling strategy

Useful resources

BBC Five animals to spot in a post-Covid financial jungle

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1973). Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cognitive psychology, 5(2), 207-232.

Gupta, S., & Shrivastava, M. (2022). Herding and loss aversion in stock markets: mediating role of fear of missing out (FOMO) in retail investors. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 17(7), 1720-1737.

Gupta, S., & Shrivastava, M. (2022). Argan, M., Altundal, V., & Tokay Argan, M. (2023). What is the role of FoMO in individual investment behavior? The relationship among FoMO, involvement, engagement, and satisfaction. Journal of East-West Business, 29(1), 69-96.

About the author

The article was written in December 2025 by SHIU Lang Chin (ESSEC Business School, Global Bachelor in Business Administration (GBBA), 2024-2026).

▶ Read all articles by SHIU Lang Chin.