In this article, Georges WAUBERT gives the reasons why governments issue debt.

In normal times, governments use debt (bills, notes and bonds) to cover expenses and finance investments that will create new wealth, which will make it possible to repay the debt. This is what companies do when they use credit to buy new machinery for example. It is also what public authorities do when they build schools, hospitals or roads that will increase the productive capacity of the country and improve the living conditions of its inhabitants. However, the interest for a state to go into debt could not be limited to this. What are the other reasons to go into debt?

Public debt allows the mobilization of private savings

The level of savings directly influences investment in the economy and, therefore, the level of consumption. However, there are many factors that can push savings away from their optimal level, i.e. the level that maximizes consumption. It is therefore necessary for a government to find solutions to adjust this level of savings. Recourse to debt is one of the solutions.

Indeed, recourse to debt is a means of mobilizing, in return for remuneration, the savings of individuals, and in particular those of households with sufficiently high incomes to save. Today, there are not enough borrowers who issue good quality assets. The proof is that interest rates are very low on public debt. Savers are competing with each other and accepting lower and lower yields for this type of savings medium. Thus, in a world of asset shortages, it is the state that will provide sufficient savings vehicles. The state is then faced with a dilemma: to provide adequate and safe savings vehicles and to increase taxes in order to pay the interest on new public debt.

Public debt helps limit fluctuations in production levels

As we have seen with the Covid-19 crisis, an economy can be confronted with one or more shocks that temporarily push the level of production away from its potential level. Such fluctuations represent a cost. Indeed, a higher volatility in the level of output translates into a lower growth rate. In addition, a temporary fall in output from its potential level can lead to the failure of long-term viable businesses.

Investments financed by debt can be used to limit the magnitude of changes in the level of output. Changes in government spending or tax obligations significantly affect the level of output. An increase in expenditure usually results in an increase in output. Thus, public debt is an effective way of stabilizing output. This is what happened during the 1980s and 1990s. Governments around the world used massive debt to support their economic activity. During the Covid-19 crisis, the “whatever it takes” approach saved many companies. However, it has also kept unprofitable companies on life support, which should have disappeared, due to a lack of hindsight.

Public debt is a redistribution within the present generations

Public debt is often presented as a burden to be borne by future generations. However, this statement is far from obvious. Indeed, it is very difficult to measure the extent of transfers between generations. Future generations will also benefit from part of the money borrowed today that will have been invested and distributed to households that will be able to save it and then pass it on to their children. Thus, it is difficult to assess the real burden of the debt for future generations.

What is more certain, however, is that the public debt is primarily a transfer within the households at the present time. The State borrows from an agent X to redistribute to an agent Y or to make an investment that will benefit an agent Z. Thus, from this point of view, the use of debt is a good tool for redistribution among households.

Related posts on the SimTrade blog

▶ Georges WAUBERT Government debt

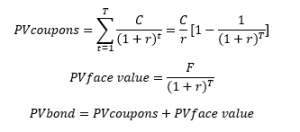

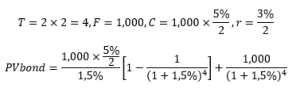

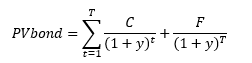

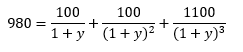

▶ Georges WAUBERT Bond valuation

▶ Georges WAUBERT Bond markets

▶ Bijal GANDHI Credit Rating

▶ Jayati WALIA Credit risk

Useful resources

Rating agencies

About the author

Article written in July 2021 by Georges WAUBERT