In this article, Hadrien PUCHE (ESSEC Business School, Grande École Program, Master in Management, 2023-2027) comments on Robert Arnott’s famous quote, exploring how it relates to risk-taking, behavioral biases, and the mindset required to achieve consistent, long-term performance.

About Robert Arnott

Robert Arnott

Source: Research Affiliates

Robert D. Arnott (born 1954) is an American investor, researcher, and entrepreneur. He is the founder and chairman of Research Affiliates, a firm known for its pioneering work on smart beta and alternative indexing strategies. Arnott has written extensively on asset allocation, portfolio construction, and factor investing, often challenging traditional assumptions about market efficiency.

Throughout his career, Arnott has emphasized that the best investment opportunities emerge when investors are willing to leave their comfort zone, particularly when markets are volatile, sentiment is negative, and uncertainty dominates.

Analysis of the quote

When Arnott says, “In investing, what is comfortable is rarely profitable,” he highlights a fundamental paradox of financial markets: comfort and profit rarely coexist.

Comfort comes from stability, familiarity, and consensus. Yet, markets reward those who act rationally in uncomfortable moments; those who buy when others sell and remain calm when others panic. Profitable investing often requires doing what feels counterintuitive.

However, this quote does not promote reckless risk-taking. Instead, it reminds us that genuine investment opportunities often arise in periods of uncertainty and fear, when prices deviate from intrinsic value. Success lies in maintaining discipline and conviction when others lose theirs.

Moreover, this insight resonates with Frank Knight’s distinction between risk and uncertainty. While risk can be measured and priced, true uncertainty is unknowable and unpredictable. Investing in moments of discomfort often means confronting this unmeasurable uncertainty, and taking opportunities when most investors hesitate.

Case study: March 2020 – Investing during the Covid crisis

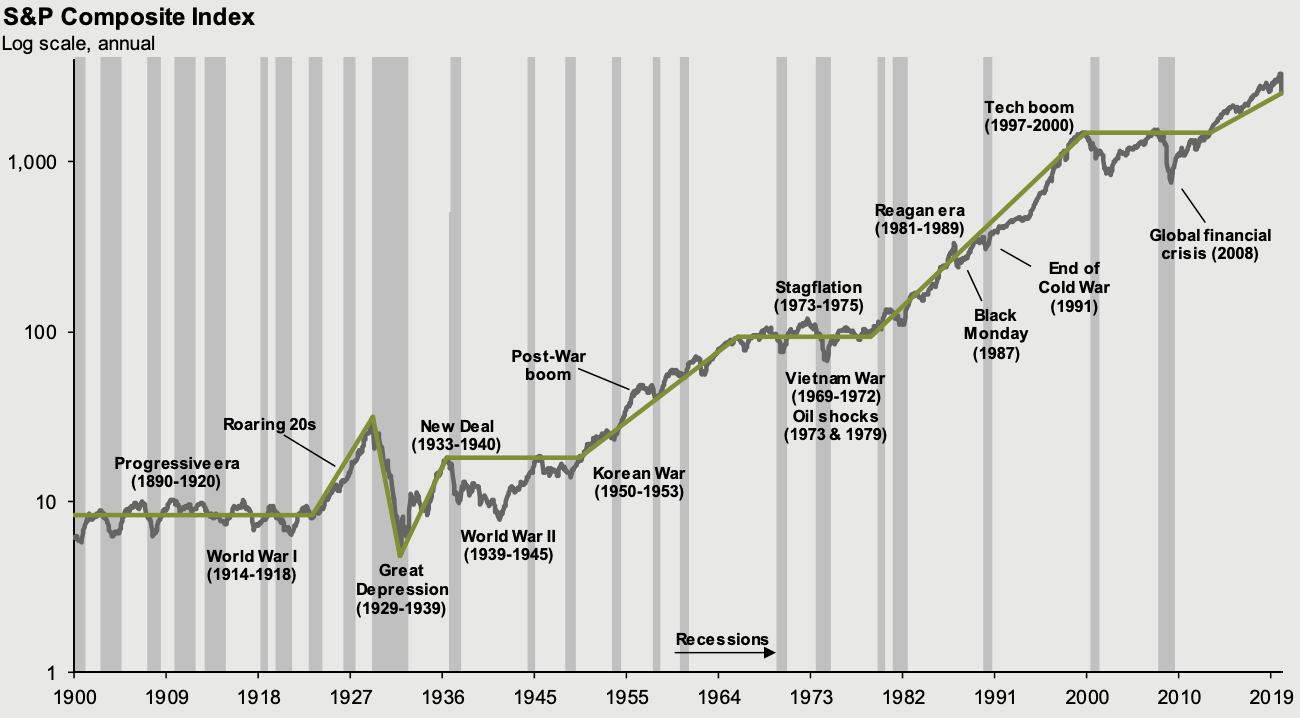

Between February and March 2020, the S&P 500 index fell by more than 30% as investors panicked and rushed to sell their holdings. However, those who bought stocks during the downturn (or even simply stayed invested) saw the market recover to new highs within just a few months. The real losses came not from the crash itself, but from panic selling at the worst possible moment.

To better understand why the market reaction was so violent during this period, it is useful to look at the VIX index, often referred to as the “fear gauge” of financial markets. The VIX measures expected volatility based on S&P 500 option pricing, and it tends to spike when uncertainty and investor anxiety rise.

In the graph below, which compares the performance of the S&P 500 and the VIX over the 2020 Covid market crash, we can clearly see how moments of market stress correspond to sharp increases in the VIX.

The S&P 500 declines at the same time the VIX surges, illustrating the sharp rise in market fear and uncertainty.

Source: TradingView

Economic / Financial concepts related to the quote

I present below three financial concepts: the risk–return tradeoff, the psychology behind discomfort, and contrarian investing and market cycles.

1 – The risk–return tradeoff

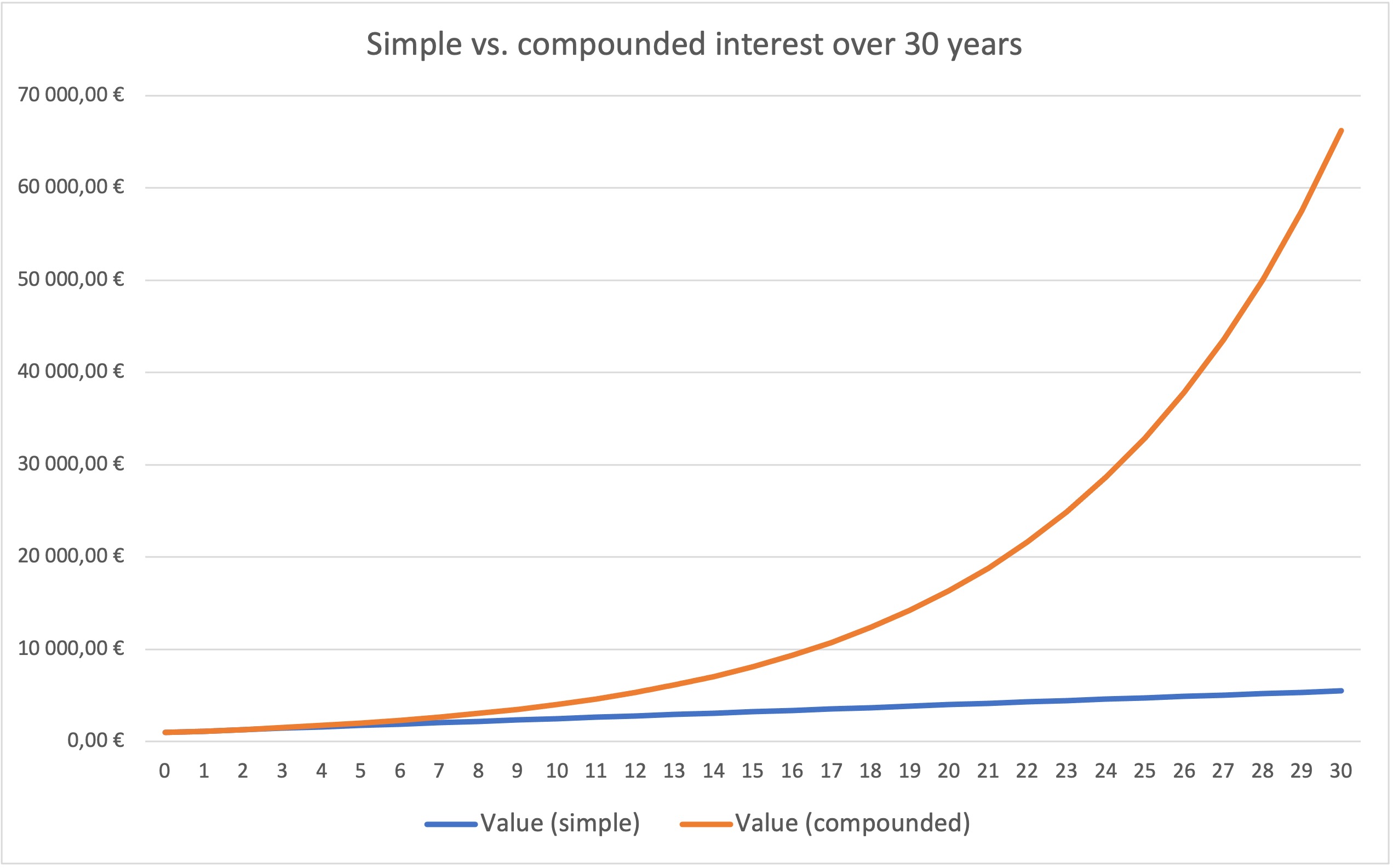

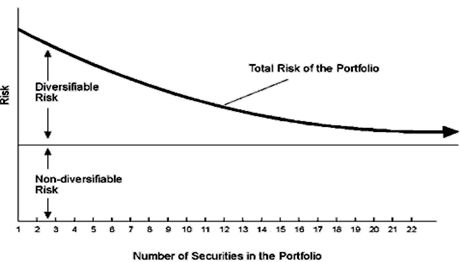

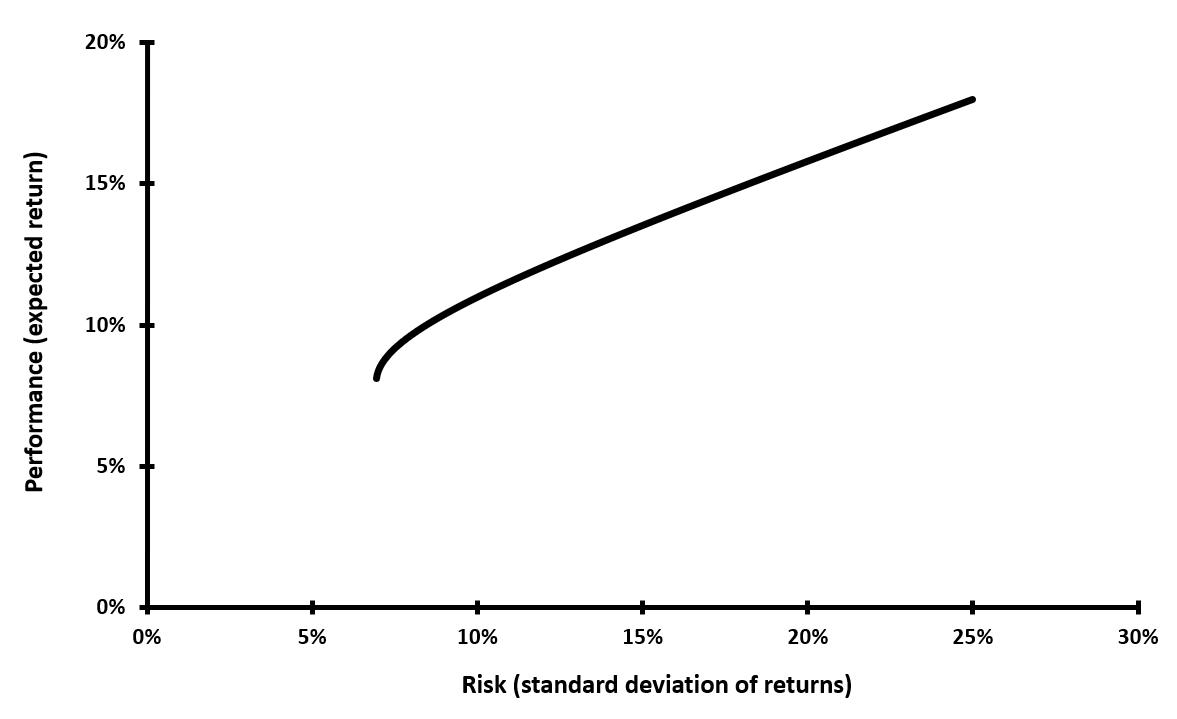

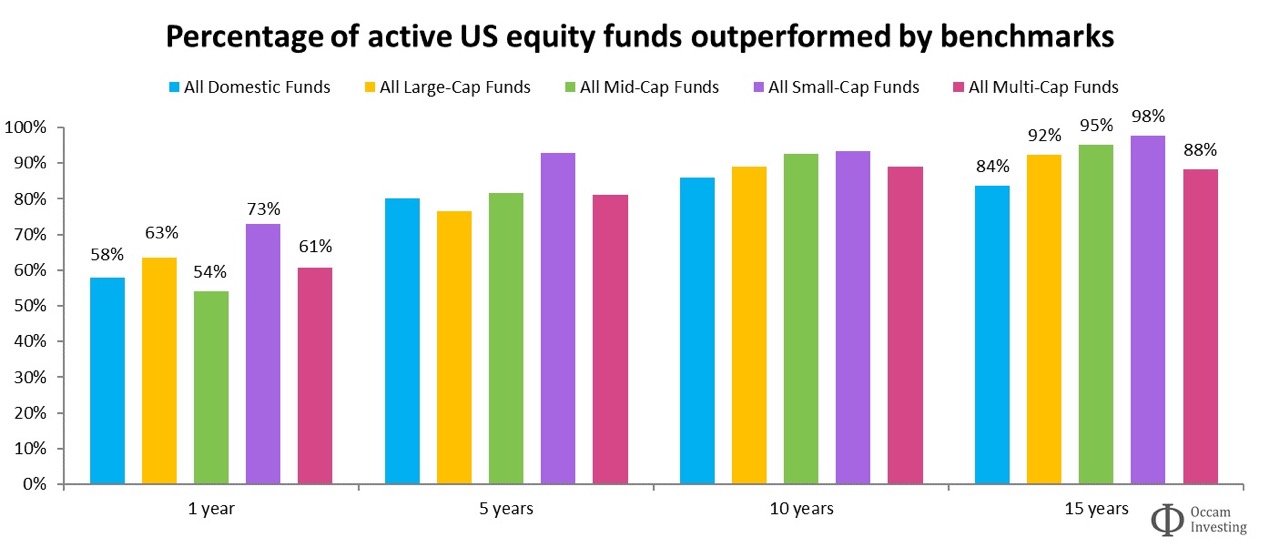

Arnott’s quote connects directly to the risk–return tradeoff, a cornerstone of modern portfolio theory (Harry Markowitz, 1952). The principle is simple but powerful: higher expected returns are only possible when investors accept higher levels of risk.

In quantitative terms, risk is often measured by metrics such as volatility (the standard deviation of returns) or the Value at Risk (the expected maximum loss that could occur on a given period). Assets with higher volatility tend to offer higher average returns to compensate investors for the uncertainty they bear.

This relationship is evident across asset classes: equities have historically outperformed bonds, and small-cap or emerging market stocks have outperformed large, stable firms, precisely because they are riskier and therefore less “comfortable” to hold.

| Money Markets | Bonds (20Y TB) | Equities (S&P 500) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Historical returns | 3.3% | 5.7% | 10.3% |

| Historical volatility | 0.1 to 1% | 10% | 15 to 20% |

Source: “Long-Term Performance”, Martin Capital, and CFA Institute.

Those who prioritize comfort, by investing in stable, low-volatility assets such as government bonds or blue-chip stocks, may achieve safety but at the cost of limited upside. In contrast, investors willing to face volatility intelligently, through diversification, disciplined portfolio construction, and long-term perspective, can capture higher returns over time.

Ultimately, discomfort is not a flaw of investing, but rather the price of better returns. As every investor learns sooner or later, there is no reward without risk, and no performance without volatility.

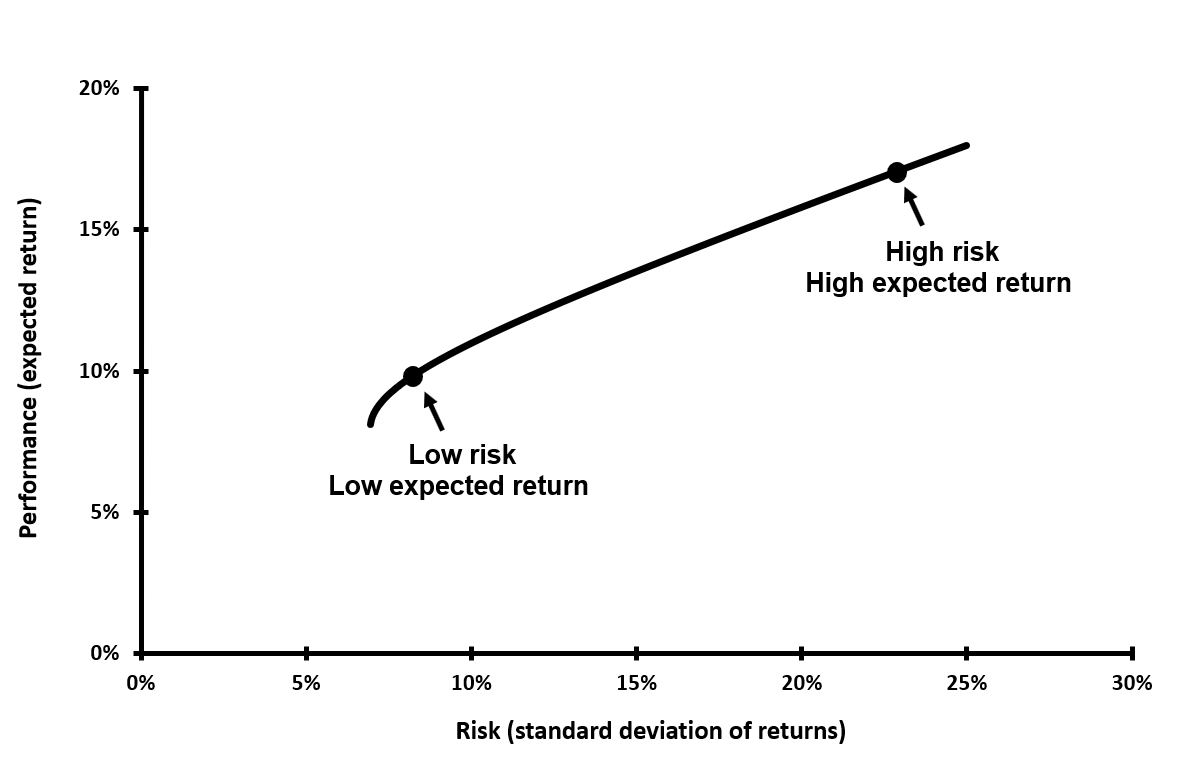

This relationship between risk and return is often illustrated by the efficient frontier: as investors take on more risk (measured by the volatility of returns), the expected long-term return increases. The graph below shows this fundamental tradeoff, highlighting how low-risk assets typically offer modest returns, while higher-risk assets provide the potential for superior performance.

2 – The psychology behind discomfort

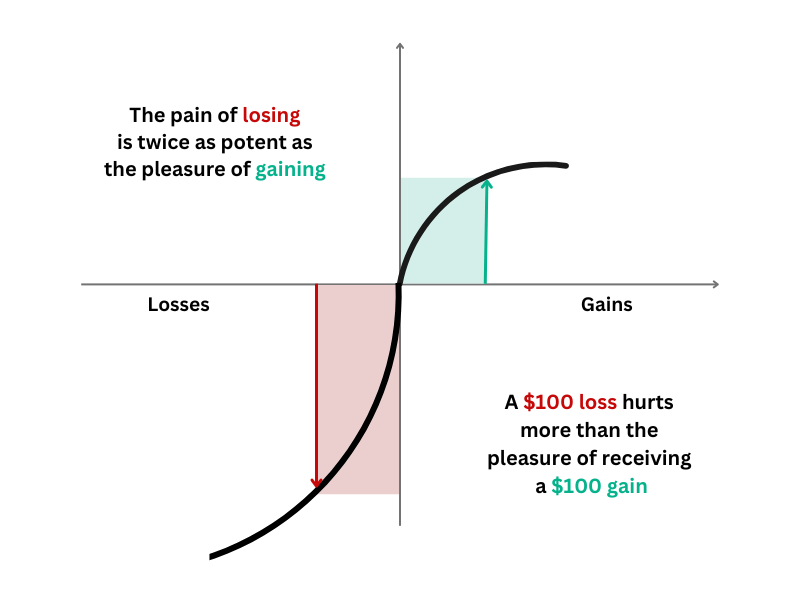

Arnott’s insight aligns closely with behavioral finance, particularly Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky’s concept of loss aversion. The idea is that the pain of losing is psychologically about twice as powerful as the pleasure of gaining.

The chart below illustrates this asymmetry: while gains produce only a moderate rise in satisfaction, losses trigger a disproportionately strong emotional reaction, shaping many irrational investment decisions.

This bias makes investors instinctively avoid risk, even when it offers potential rewards.

In financial markets, this aversion to loss often translates into herd behavior: investors seek comfort in doing what others do, buying overvalued assets during booms and selling undervalued ones during downturns. While this may feel safe in the short term, it systematically destroys value over time.

Legendary investors such as Warren Buffett and Howard Marks have long warned against this mindset: “Be fearful when others are greedy, and greedy when others are fearful.” True comfort in markets is often a sign of danger, not safety.

A good example is the dot-com bubble of 2000. At the time, investing in fast-growing tech stocks felt like the comfortable and obvious choice, as prices seemed to rise endlessly. Yet when the bubble burst, it became clear that this comfort had been an illusion, and that discomfort, not consensus, is where opportunity truly lies.

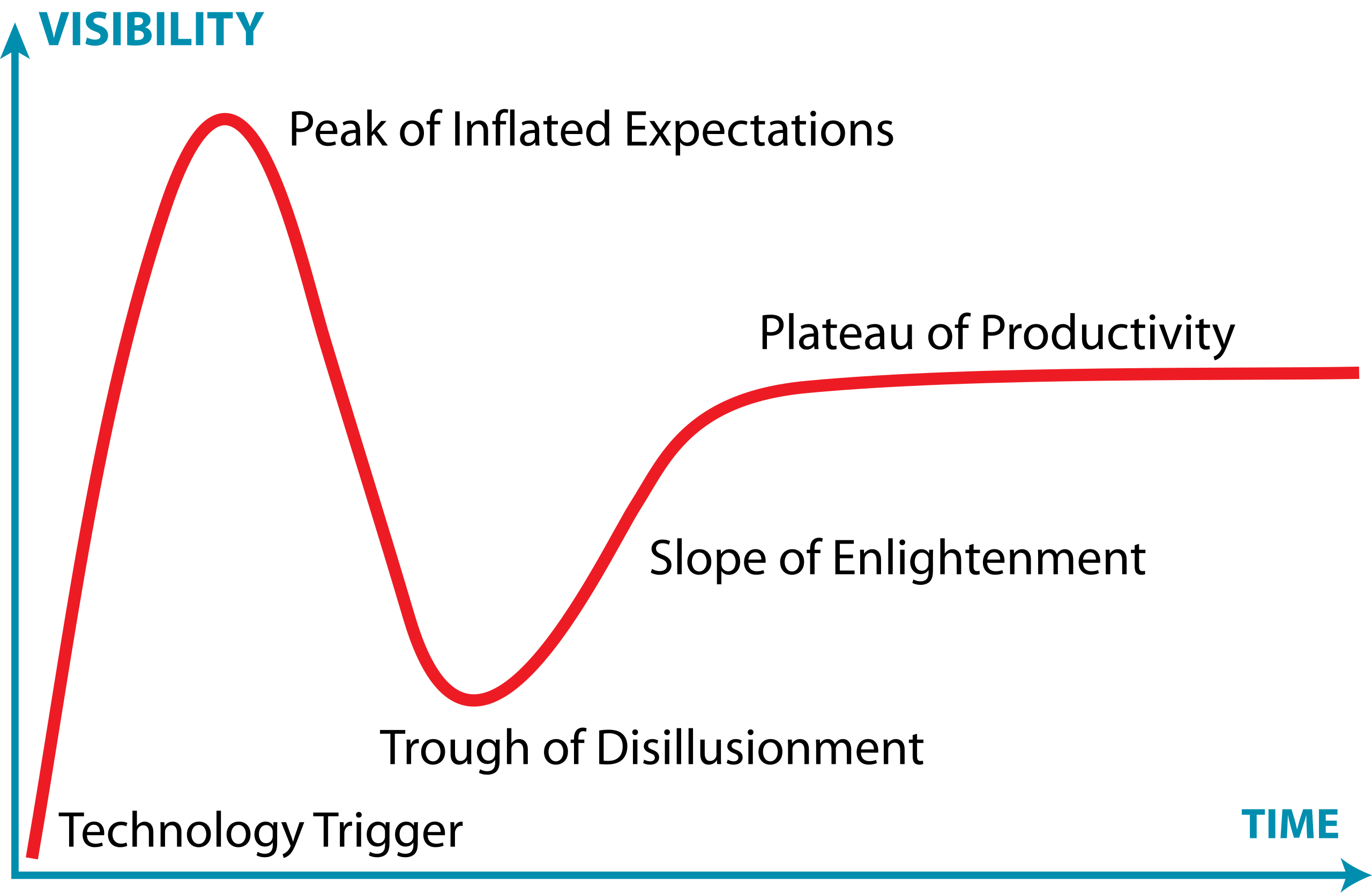

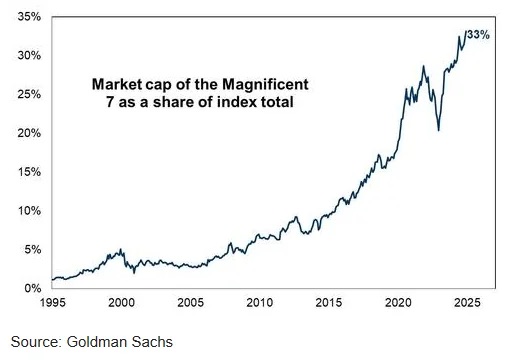

3 – Contrarian investing and market cycles

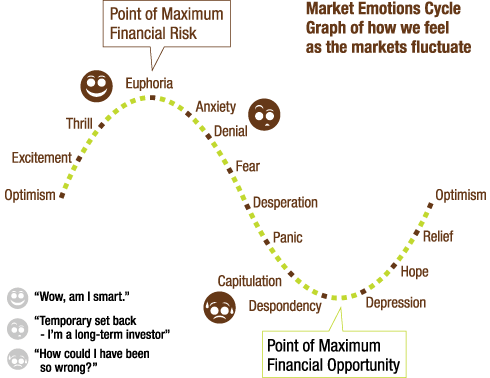

Arnott’s quote also resonates with the philosophy of contrarian investing: the art of going against prevailing market sentiment. It means buying when fear dominates and selling when euphoria prevails.

As Minsky explains in his Financial Instability Hypothesis, periods of stability paradoxically encourage increasing risk-taking, as market participants move from hedge finance to speculative and then Ponzi finance. This endogenous dynamic inevitably leads to points of fragility where confidence collapses. Kindleberger, in Manias, Panics, and Crashes, provides empirical illustration: markets swing from euphoria to distress, from boom to bust, before stability gradually returns and the cycle begins anew.

The chart below visually maps this emotional cycle, highlighting how investor psychology typically evolves from euphoria to panic and back to optimism.

The most profitable opportunities often emerge during moments of maximum discomfort: recessions, crises, or market panics, when prices are depressed but fundamentals remain sound. As Sir John Templeton famously said, “The time of maximum pessimism is the best time to buy.”

However, acting against the crowd is far from easy. It requires not only analytical conviction but also emotional discipline, the ability to stay rational when everyone else reacts emotionally. This mental resilience is what separates long-term investors from speculators driven by short-term noise.

My opinion about this quote

I find Arnott’s statement particularly relevant, at a time when social media and short-term performance metrics dominate investor psychology. Platforms such as X (Twitter), Reddit, or TikTok amplify herd behavior by rewarding consensual views rather than conviction. True investment success requires patience, analytical thinking, and the ability to tolerate discomfort.

To me, this quote extends beyond finance: it reflects a mindset of resilience and independence, valuable in career decisions, entrepreneurship, and life in general, because growth rarely happens in comfort zones.

Why should you be interested in this post?

This quote provides a timeless reminder for students and young professionals: comfort is the enemy of progress.

The rise of AI-driven trading, quantitative strategies, and passive investing has made markets appear more predictable and automated. This can create new forms of comfort, a belief that algorithms or index funds can replace human judgment. However, Arnott’s message reminds us that critical thinking, curiosity are still needed to outperform others.

As Arnott’s principle suggests, growth rarely happens in comfort zones. Whether in markets, careers, or personal development, long-term success comes from embracing uncertainty intelligently, and finding opportunity where others see discomfort.

Related posts on the SimTrade blog

▶ Youssef LOURAOUI Asset allocation techniques

▶ Youssef LOURAOUI Smart Beta strategies: between active and passive allocation

▶ Youssef LOURAOUI Markowitz Modern Portfolio Theory

Useful Resources

- Ackert, L. F., & Deaves, R. (2010). Behavioral Finance: Psychology, Decision-Making, and Markets. South-Western Cengage Learning.

- Research Affiliates. (n.d.). Official Website.

- Martin Capital. (2020). Long-Term Performance. Retrieved from https://www.martincapital.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Long-Term-Performance-Presentation-2020.pdf

Business Books

- Graham, B. (1949). The Intelligent Investor: A Book of Practical Counsel (Rev. ed.). Harper & Brothers.

Academic Articles

- Arnott, R. D. (2003). The Fundamental Index: A Better Way to Invest. Financial Analysts Journal, 59.

- Arnott, R. D. (2005). The Most Dangerous Equation. Financial Analysts Journal, 61.

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–291.

- Markowitz, H. (1952). Portfolio Selection. The Journal of Finance, 7(1), 77–91.

Classic Economic & Finance Works

- Kindleberger, C. P. (1978). Manias, Panics, and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises. New York: Basic Books.

- Minsky, H. P. (1992). The Financial Instability Hypothesis. Working Paper No. 74, Jerome Levy Economics Institute.

About the Author

This article was written in November 2025 by Hadrien PUCHE (ESSEC Business School, Grande École Program, Master in Management, 2023-2027).

▶ Discover all articles by Hadrien PUCHE