Understand the mechanism of inflation in a few minutes?

In this article, Louis DETALLE (ESSEC Business School, Grande Ecole Program – Master in Management, 2020-2023) explains everything you have to know about inflation.

What is inflation and how can it make us poorer?

In a liberal economy, the prices of goods and services consumed vary over time. In France, for example, when the price of wheat rises, the price of wheat flour rises and so the price of a loaf of bread may also rises as a consequence of the rise in the price of the raw materials used for its production… This small example is only designed to make the evolution of prices concrete for one good only. It helps us understand what happens when the increase in price happens not only for a loaf of bread, but for all the goods of an economy.

Inflation is when prices rise overall, not just the prices of a few goods and services. When this is the case, over time, each unit of money buys fewer and fewer products. In other words, inflation gradually erodes the value of money (purchasing power).

If we take the example of a loaf of bread which costs €1 in year X, while the price of the 20g of wheat flour contained in a loaf is 20 cents. In year X+1, if the 20g of wheat flour now costs 22 cents, i.e., a 10% increase over one year, the price of the loaf of bread will have to reflect this increase, otherwise the baker will be the only one to suffer the increase in the price of his raw material. The price of a loaf of bread will then be €1.02.

We can see that here, with one euro, i.e., the same amount of the same currency, from one year to the next, it is not possible for us to buy a loaf of bread because it costs €1.02 and not €1 anymore.

This is a very schematic way of understanding the mechanism of inflation and how it destroys the purchasing power of consumers in an economy.

How is the inflation computed and what does a x% inflation mean?

In France, Insee (Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques in French) is responsible for calculating inflation. It obtains it by comparing the price of a basket of goods and services each month. The content of this basket is updated once a year to reflect household consumption patterns as closely as possible. In detail, the statistics office uses the distribution of consumer expenditure by item as assessed in the national accounts, and then weights each product in proportion to its weight in household consumption expenditure.

What is important to understand is that Insee calculates the price of an overall household expenditure basket and evaluates the variation of its price over time.

When inflation is announced at X%, this means that the overall value spent in the year by a household will increase by X%.

However, if the price of goods increases but wages remain the same, then purchasing power deteriorates, and this is why low-income households are the most affected by the rise in the price of everyday goods. Indeed, low-income households can’t easily cope with a 10% increase in price of their daily products, whereas the middle & upper classes can better deal with such a situation.

What can we do to reduce inflation?

It is the regulators who control inflation through major macroeconomic levers. It is therefore central banks and governments that can act and they do so in various ways (as an example, we use the context of the War in Ukraine in 2022):

They raise interest rates: when inflation is too high, central banks raise interest rates to slow down the economy and bring inflation down. This is what the European Central Bank (ECB) has just done because of the economic consequences of the War in Ukraine. The economic sanctions have seen the price of energy commodities soar, which has pushed up inflation.

Blocking certain prices: This is what the French government is still doing on energy prices. Thus, in France, the increase in gas and electricity tariffs will be limited to 15% for households, compared to a freeze on gas prices and an increase limited to 4% for electricity in 2022. Without this “tariff shield”, the French would have had to endure an increase of 120%.

Distribute one-off aid: These measures are often considered too costly and can involve an increase in salaries.

Bear in mind that “miracle” methods do not exist, otherwise inflation would never be a subject discussed in the media. However, these three methods are the most used by governments and central banks but only time will tell us whether they succeed.

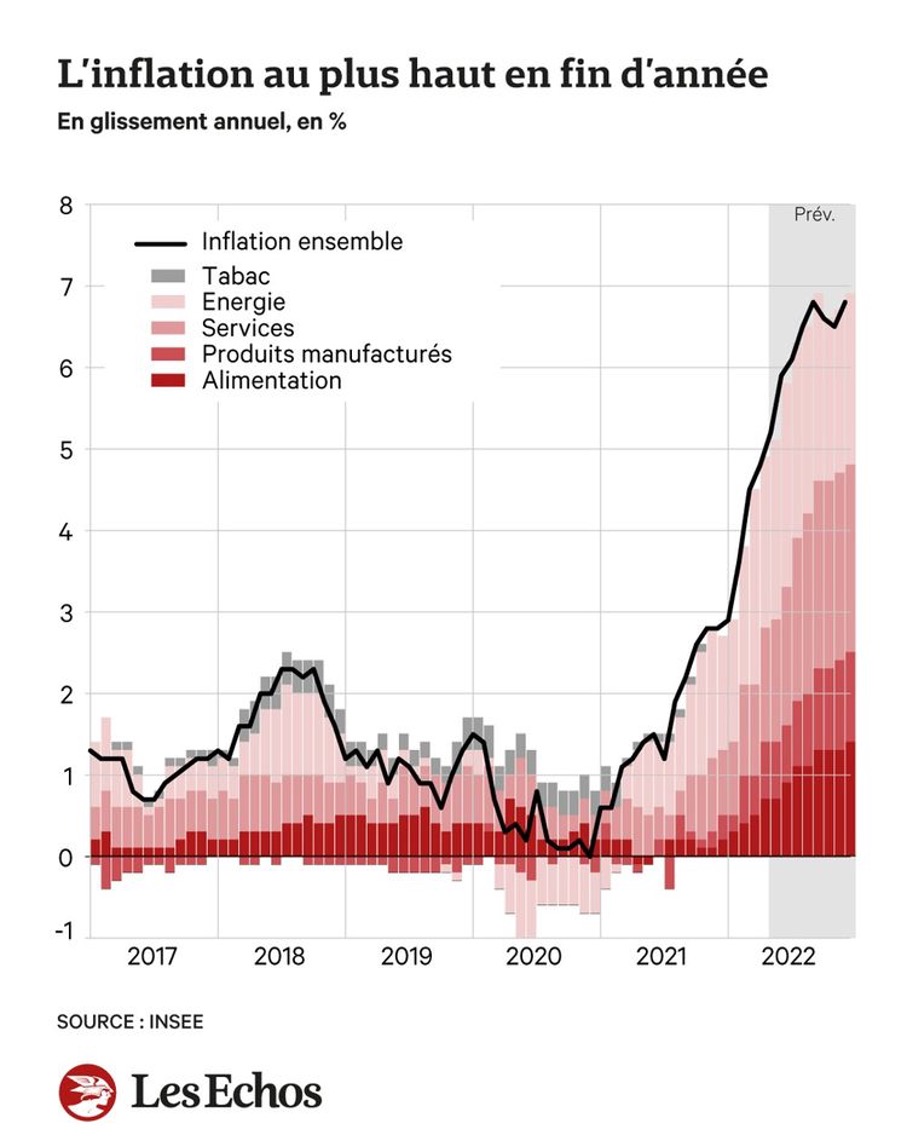

Figure 1. Inflation in France.

Source: Insee / Les Echos.

Useful resources

Inflation rates across the World

Insee’s forecast of the French inflation rate

Related posts on the SimTrade blog

▶ Bijal GANDHI Inflation Rate

▶ Alexandre VERLET Inflation and the economic crisis of the 1970s and 1980s

▶ Alexandre VERLET The return of inflation

▶ Raphaël ROERO DE CORTANZE Inflation & deflation

About the author

The article was written in October 2022 by Louis DETALLE (ESSEC Business School, Grande Ecole Program – Master in Management, 2020-2023).