Rise of SPAC investments as a medium of raising capital

In this article, Daksh GARG (ESSEC Business School, Master in Strategy & Management of International Business (SMIB), 2020-2021) talks about the rise of SPAC investments as a medium of raising capital. Imagine someone famous asking you to invest in a company. Chances are, you will want to know more. As it turns out, there is no company, at least not yet. Will you invest in it with your money?

What are SPACs?

‘SPAC’ stands for Special Purpose Acquisition Companies. SPACs are a type of blank-check company that pools funds to finance mergers and acquisitions (M&A) transactions.

Once shunned by investors, SPACs have become an increasingly popular method in recent years to list companies on a stock exchange.

SPACs are shell companies with no actual commercial operations but are created solely for raising capital through an initial public offering – or IPO – to acquire later a private company. This is done by selling common stocks – with shares commonly sold at $10 a piece – and a warrant, which gives investors the preference to buy more stocks later at a fixed price.

Once the funds are raised, they will be kept in a trust until one of two things happen:

The management team of the SPAC — also known as sponsors — identifies a company of interest, which will then be taken public through an acquisition, using the capital raised in the SPAC IPO.

If the SPAC fails to merge or acquire a company within a deadline typically two years — the SPAC will be liquidated, and investors will get their money back.

SPACs have existed in one form or another as early as the 1990s, typically as a last resort for smaller companies to go public. The number of SPAC IPOs has waxed and waned over the years in tandem with the economic cycles. SPACs have been making a resurgence of late.

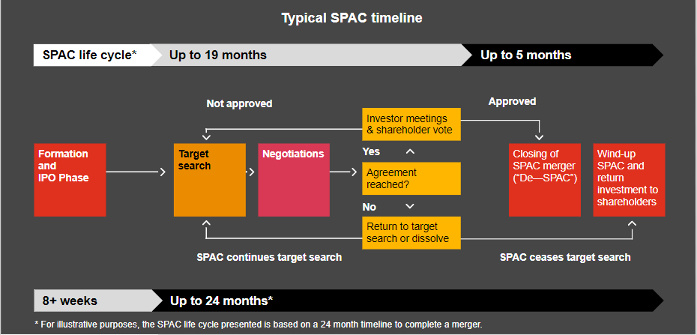

The timeline for SPAC

Figure 1 gives the typical timeline for a SPAC investment. Following the IPO, the proceeds for a SPAC are placed in a fund. In the meantime, the SPAC has to merge with a target company. If it is not able to do that in the time frame, the SPAC has to liquidate and the IPO proceeds are returned to the shareholders.

Figure 1. Typical SPAC timeline.

Source: PWC accounting advisory

Difference between a traditional IPO and a SPAC

There are several ways a private company can go public (being quoted on the stock market). The most common route is through a traditional IPO, where the company is subject to regulatory and investor scrutiny of its audited financial statements.

An investment bank is usually hired by the company to underwrite the IPO, which usually takes 4-6 months to complete. This involves roadshows and pitch meetings between company executives and potential investors to drum up interest and demand in its shares. And not all IPOs succeed. A very famous example is that of a co-working-space company called WeWork withdrew its high-profile IPO in 2019 amid weak demand for its shares after massive losses and leadership controversies were revealed. Other companies such as Spotify and Slack went public through direct listings, saving on fees paid to middlemen such as investment banks, although there are more risks involved. And while private companies listed through SPACs are similar to reverse takeovers, such as the case for insolvent fintech company Wirecard, they are different in that SPACs start off on a clean slate and have lower risks. Because SPACs are nothing more but shell companies, their track records depend on the reputation of their management teams. By skipping the roadshow process, SPAC IPOs also typically are listed in a much shorter time. This leads to some investors to become wary of buying shares in companies listed through SPACs due to the lack of scrutiny compared to traditional IPOs.

SPAC sponsors also typically receive 20% of founder shares in the company at a heavily discounted price, also known as the “promote.” This essentially dilutes the ownership of public shareholders.

Performance of traditional IPOs compared to SPAC IPOs

According to Bloomberg, a study of 56 SPACs that completed acquisitions or mergers since the start of 2018 found that they tend to underperform the S&P 500 during a three, six and 12-month period after the transaction. A separate study of blank-check companies in the U.S. organized between 2015 and 2019 found that the majority are trading below the standard price of $10 per share. Between 2017 and the middle of 2019, there were slightly over 100 SPACs in the U.S., with an average return of a mere 2%.

Even before the pandemic, SPACs were already on the rise, buoyed by the equity boom and hot IPO market in 2019. While the pandemic has slowed the pipeline of traditional IPOs, SPACs have increased.

In fact, funds raised through SPACs outpaced traditional IPOs in August 2020 — a rarity on Wall Street. In the first ten months of 2020, there were 165 SPAC IPOs globally, of which 96% of them were listed in the U.S. While largely an American phenomenon, SPACs have caught the attention of investors in other jurisdictions.

In 2018, Antony Leung, the former finance secretary of Hong Kong, raised $1.5 billion on the New York Stock Exchange through his SPAC, which bought a mainland hospital chain a year later.

Other players include Masayoshi Son’s SoftBank, and the investment arm of Chinese state-owned conglomerate CITIC Group. Despite having sponsors from Asia looking to acquire international companies, these SPACs are ultimately listed in the U.S.

One main reason is the different rules for SPACs across jurisdictions. In the U.S., investors can vote to approve the acquisition the SPAC proposes or redeem their funds if they do not support the proposed deal.

This, however, isn’t a requirement in some European jurisdictions, including the U.K. There is also a lock-in period for British investors once an acquisition is announced until the approval of the prospectus, which ties them into deals that they may not support in that indefinite period.

Future of SPACs

As SPAC activity reaches fever pitch in the U.S., regulators are putting these blank-check companies under the microscope. Competition to the IPO process is probably a good thing, but for good competition and good decision-making, you need good information. And one of the areas in the SPAC space that I’m particularly focused on is incentives and compensation to the SPAC sponsors. As more ordinary investors jump on the SPAC bandwagon, experts are concerned that this will overheat markets and affect any fragile economic recovery. While SPACs provide a straightforward route to invest through a trusted intermediary, its performance so far means that it is a dicey bet for ordinary investors.

Why should I be interested in this post?

If you are interested in how big companies are going public, SPAC is one of the most interesting phenomena which is going to transform the financial industry. So, if you are planning to work for top underwriting firms or big banks or on Wall Street, you should have in-depth knowledge on how SPACs work and what are some of their advantages and disadvantages.

Useful resources

PWC How special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs) work Accessed November 2, 2021.

PWC Analysis: De-SPACing Successes Refuel Hot SPAC IPO Market Accessed November 2, 2021.

Related posts on the SimTrade blog

▶ Suyue MA Expeditionary experience in a Chinese investment banking boutique

▶ Raphaël ROERO DE CORTANZE In the shoes of a Corporate M&A Analyst

About the author

The article was written in November 2021 by Daksh GARG (ESSEC Business School, Master in Strategy & Management of International Business (SMIB), 2020-2021).