Investing is often a battle with our own emotions. We see prices rise sharply and crash just as fast, and this can lead to very bad investment decisions. However, Charlie Munger’s wisdom comes once again handy, to remind us to avoid overlooking at prices all day-long, because “Investing is stupid if you’re more worried about short-term volatility than long-term quality”.

In this article, Hadrien PUCHE (ESSEC Business School, Grande École Program, Master in Management, 2023-2027) explores why Munger’s wisdom serves as a welcome reminding of the difference between short-term price and long-term value.

Charlie Munger: the architect of quality investing

Charlie Munger

Source : Fortune

Charlie Munger (1924–2023) was far more than a mere lieutenant to Warren Buffett; he was the primary intellectual catalyst who shifted Berkshire Hathaway’s strategy away from the traditional “cigar butt” school of Benjamin Graham. While Graham sought “fair businesses at a great price,” Munger convinced Buffett of the immense power found in “great businesses at a fair price”. The 1989 Letter to Shareholders is particularly famous for the “Mistakes of the First Twenty-Five Years” where Munger’s influence is clear.

He achieved this by integrating a multidisciplinary framework (incorporating insights from psychology, biology, and physics) to decode the complexities of the financial world, ultimately arguing that the quality of a business is the only reliable engine for long-term wealth.

It has to be said that there is no record of Charlie Munger saying these exacts words, but it does summarize well his investment philosophy.

An analysis of this quote

Munger’s philosophy rests upon the bedrock observation that the stock market operates as a “weighing machine” in the long run, even if it behaves like a “voting machine” in the short term. He famously dismissed the academic obsession with volatility as a proxy for risk, arguing instead that a twenty-percent drawdown is not a “loss” unless the investor is forced to sell, or if the fundamental earning power of the business has permanently deteriorated. Real risk, in the Munger school of thought, is defined strictly as the permanent loss of capital (the inability to recover one’s initial investment), which has almost no correlation with the standard deviation of daily price movements.

Furthermore, Munger recognized that investors are often their own worst enemies, due to “loss aversion” (a biological vestige of our evolutionary past where a declining stock price triggers a “fight or flight” response). He suggested that if an individual lacks the temperament to ignore these short-term signals, they are effectively paying an “emotional tax” that prevents them from reaching the higher echelons of compounding.

Indeed, the first rule of compounding is to never interrupt it unnecessarily; by reacting to volatility, investors often liquidate high-quality assets during temporary market drawdowns, effectively resetting their exponential growth clock and sacrificing future prosperity.

Financial concepts related to the quote

This quote reminds me of a few very interesting financial concepts that you may be interested in.

The flaw with Beta in the modern portfolio theory

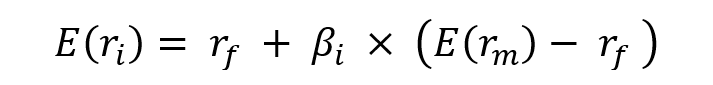

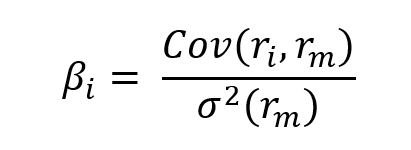

In the world of academic finance (specifically within the Capital Asset Pricing Model, or CAPM), risk is mathematically defined as Beta (β), which measures the sensitivity of an asset’s returns relative to the broader market.

As a reminder, the CAPM expresses the expected return of an asset as a function of the risk-free rate, the beta of the asset, and the expected return of the market. The main result of the CAPM is a simple mathematical formula that links the expected return of an asset to these different components. For an asset i, it is given by:

Where:

- E(ri) represents the expected return of asset i

- rf the risk-free rate

- βi the measure of the risk of asset i

- E(rm) the expected return of the market

- E(rm)- rf the market risk premium.

The risk premium for asset i is equal to βi(E(rm)- rf), that is the beta of asset i, βi, multiplied by the risk premium for the market, E(rm)- rf.

In this model, the beta (β) parameter is a key parameter and is defined as:

Where:

- Cov(ri, rm) represents the covariance of the return of asset i with the return of the market

- σ2(rm) the variance of the return of the market.

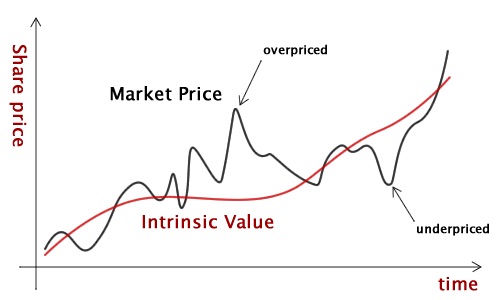

However, Munger viewed this as a fundamental intellectual error. From an analytical standpoint, if a company’s intrinsic value remains stable while its price drops significantly, the “risk” (the probability of overpaying) has actually decreased, even though the “volatility” (the Beta) has technically increased.

For the rational investor, volatility should be viewed as a provider of liquidity and favorable entry points rather than a threat. When the market overreacts to macro-economic data or geopolitical tension, it creates a “Rationality Gap” where high-quality firms are temporarily mispriced. Munger argued that those who can remain stoic during these periods are the ones who capture the “premium of patience.”

In essence, while the academics are busy calculating standard deviations, the Munger-style investor is busy calculating whether the business’s ability to generate cash remains intact.

What really matters for Charlie Munger is to buy the stock when it is underpriced, and selling it when it is overpriced.

Source: Elearnmarkets Blog

ROIC, and the dynamics of the “Economic Moat”

For Munger, “Quality” was not a vague descriptor but a quantifiable financial phenomenon centered on one main metric: Return on Invested Capital (ROIC). The formula is elegant in its simplicity:

Munger observed that over a forty-year holding period, a stock’s total return will inevitably converge toward its ROIC. Crucially, for value to be created, this ROIC must be higher than the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC). If you hold a business that earns six percent on its capital for decades—barely matching its cost of capital—you will ultimately earn a six percent return, regardless of whether you bought it at a “bargain” or a “fair” price. Conversely, if a business earns eighteen percent on capital, the positive spread over its WACC creates a compounding effect that will eventually dwarf any initial valuation premium you paid.

However, high ROIC is a magnet for competition, which is why Munger prioritized companies with a “Economic Moat.” This refers to a structural barrier (such as the brand equity of Coca-Cola, the network effects of Alphabet, or the high switching costs of Microsoft) that prevents competitors from eroding those high returns. Without a moat, the spread between ROIC and WACC is merely a temporary state before mean-reversion takes hold. Therefore, analyzing a business involves a deep dive into its competitive advantages to ensure that its high ROIC is sustainable over decades, and not just over a few quarters.

Time Arbitrage and Tax Efficiency

One big advantage that an individual investor has over a professional fund manager is the concept of “Time Arbitrage.” Most institutional managers are constrained by quarterly benchmarks, and the pressure to avoid “tracking error” (falling behind the index), which forces them to react to short-term volatility to protect their career longevity. However, by extending the time horizon to ten or twenty years, an investor exit this hyper-competitive arena where most traders operate, and enters a space where patience is the primary competitive edge.

This long-term orientation also creates a significant (yet often overlooked) financial benefit: tax efficiency. By refusing to sell during volatile periods, the investor avoids triggering capital gains taxes, which allows the “unpaid taxes” to remain within the investment, and compound for free.

As Munger frequently noted, the “big money” is found in the waiting. By minimizing turnover, you maximize the terminal value of your portfolio, by ensuring that the engine of compounding is never throttled by unnecessary friction or tax leakage.

My opinion on this quote

In my view, this quote is a very interesting take on financial rationality. It is a rejection of the “noise” that defines modern electronic trading. What I find most compelling is Munger’s insistence that volatility is not a hazard, but rather the price of admission for superior returns (a concept many students struggle to internalize when they first encounter the volatility-centric models of academic finance).

To me, Munger is arguing that the market is often a theatre of the absurd where prices decouple from reality due to human emotion; therefore, the only logical response for a serious investor is a disciplined focus on the structural integrity of the business (the quality) rather than the erratic pulse of the stock price.

I believe that the “stupidity” Munger refers to is the intellectual laziness of letting a falling price dictate your perception of a business’s value. It is far easier to look at a chart and feel fear, than it is to dig into a 10-K filing to verify the Return on Invested Capital (ROIC), or the durability of a competitive advantage. By prioritizing quality over volatility, we are essentially choosing to be owners of productive assets rather than gamblers on price movements; and this shift in perspective is, in my opinion, the single most important transition a young financier can make.

Why should this quote matter to you

Whether you aspire to work in Asset Management, Private Equity, or Equity Research, Munger’s perspective is a vital toolkit for professional survival. In the institutional world, you will be constantly bombarded with requests to explain “why the market is down today” or “why a portfolio company underperformed this month.”

If you focus on these short-term “wiggles” in the data, you risk becoming a mere weather reporter. Understanding Munger allows you to move beyond superficial queries and focus on the real metrics: the cash flow margins, the structural moat, the capital allocation of management…

The “ROIC” of your career path

This principle transcends stock picking and applies directly to your own professional trajectory. Think of your career through the lens of Investment vs. Volatility:

- Career Volatility: These are the temporary setbacks: a tough performance review, a project that stalls, or a hiring freeze. If you overreact to this volatility, you risk making impulsive “trades” with your career that interrupt your progress.

- Career Quality: This is the compounding value of your technical skills, your network, and your intellectual rigor. These are the assets that generate a high “Return on Invested Capital” (ROIC) for your time and effort.

In finance, the most dangerous mistake you can make is interrupting a compounding process unnecessarily. By prioritizing the “long-term quality” of your professional output over the “short-term noise” of the job market, you ensure that you are building a career that is structurally sound and capable of weathering any economic storm.

Related posts

Quotes

▶ Hadrien PUCHE “The big money is not in the buying and selling, but in the waiting.” – Charlie Munger

▶ Hadrien PUCHE “The market is never wrong, only opinions are.” – Jesse Livermore

Financial techniques

▶ Saral BINDAL Historical Volatility

▶ Jayati WALIA Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM)

▶ Youssef LOURAOUI Markowitz Modern Portfolio Theory

▶ Youssef LOURAOUI Beta

Useful resources

Kaufman, P.D. (2005) Poor Charlie’s Almanack: The Essential Wit and Wisdom of Charles T. Munger, Third Edition, Virginia Beach, VA: Donning Company Publishers.

Buffett W.E. Berkshire Hathaway Shareholder Letters Omaha, NE: Berkshire Hathaway Inc.

Frazzini A., D. Kabiller, and L.H. Pedersen (2013) Buffett’s Alpha, Working paper.

About the Author

This article was written in February 2026 by Hadrien PUCHE (ESSEC Business School, Grande École Program, Master in Management, 2023-2027).

▶ Discover all articles by Hadrien PUCHE