Modeling of the crude oil price

In this article, Youssef LOURAOUI (Bayes Business School, MSc. Energy, Trade & Finance, 2021-2022) models the market price of the crude oil.

This article is structured as follows: we introduce the crude oil market. Then, we present the mathematical foundations of Geometric Brownian Motion (GBM) model. We use this model to simulate the price of crude oil.

The crude oil market

The crude oil market represents the physical (cash or spot) and paper (futures) market where buyers and sellers acquire oil.

Nowadays, the global economy is heavily reliant on fossil fuels such as crude oil, and the desire for these resources frequently causes political upheaval due to the fact that a few nations possess the greatest reservoirs. The price and profitability of crude oil are significantly impacted by supply and demand, like in any sector. The top oil producers in the world are the United States, Saudi Arabia, and Russia. With a production rate of 18.87 million barrels per day, the United States leads the list. Saudi Arabia, which will produce 10.84 million barrels per day in 2022 and own 17% of the world’s proved petroleum reserves, will come in second. Over 85% of its export revenue and 50% of its GDP are derived from the oil and gas industry. In 2022, Russia produced 10.77 million barrels every day. West Siberia and the Urals-Volga area contain the majority of the nation’s reserves. 10% of the oil produced worldwide comes from Russia.

Throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the United States was one of the world’s largest oil producers, and U.S. corporations developed the technology to convert oil into usable goods such as gasoline. U.S. oil output declined significantly throughout the middle and latter decades of the 20th century, and the country began to import energy. Nonetheless, crude oil net imports in 2021 were at their second-lowest yearly level since 1985. Its principal supplier was the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), created in 1960, which consisted of the world’s largest (by volume) holders of crude oil and natural gas reserves.

As a result, the OPEC nations wielded considerable economic power in regulating supply, and hence price, of oil in the late twentieth century. In the early twenty-first century, the advent of new technology—particularly hydro-fracturing, or fracking—created a second U.S. energy boom, significantly reducing OPEC’s prominence and influence.

Oil spot contracts and futures contracts are the two forms of oil contracts that investors can exchange. To the individual investor, oil can be a speculative asset, a portfolio diversifier, or a hedge for existing positions.

Spot contract

The spot contract price indicates the current market price for oil, while the futures contract price shows the price that buyers are ready to pay for oil on a delivery date established in the future.

Most commodity contracts bought and sold on the spot market take effect immediately: money is exchanged, and the purchaser accepts delivery of the commodities. In the case of oil, the desire for immediate delivery vs future delivery is limited, owing to the practicalities of delivering oil.

Futures contract

An oil futures contract is an agreement to buy or sell a specified number of barrels of oil at a predetermined price on a predetermined date. When futures are acquired, a deal is struck between buyer and seller and secured by a margin payment equal to a percentage of the contract’s entire value. The futures price is no guarantee that oil will be at that price on that date in the future market. It is just the price that oil buyers and sellers anticipate at the time. The exact price of oil on that date is determined by a variety of factors impacting the supply and demand. Futures contracts are more frequently employed by traders and investors because investors do not intend to take any delivery of commodities at all.

End-users of oil buy on the market to lock in a price; investors buy futures to speculate on what the price will be in the future, and they earn if they estimate correctly. They typically liquidate or roll over their futures assets before having to take delivery. There are two major oil contracts that are closely observed by oil market participants: 1) West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude, which trades on the New York Mercantile Exchange, serves as the North American oil futures benchmark (NYMEX); 2) North Sea Brent Crude, which trades on the Intercontinental Exchange, is the benchmark throughout Europe, Africa, and the Middle East (ICE). While the two contracts move in tandem, WTI is more sensitive to American economic developments, while Brent is more sensitive to those in other countries.

Mathematical foundations of the Geometric Brownian Motion (GBM) model

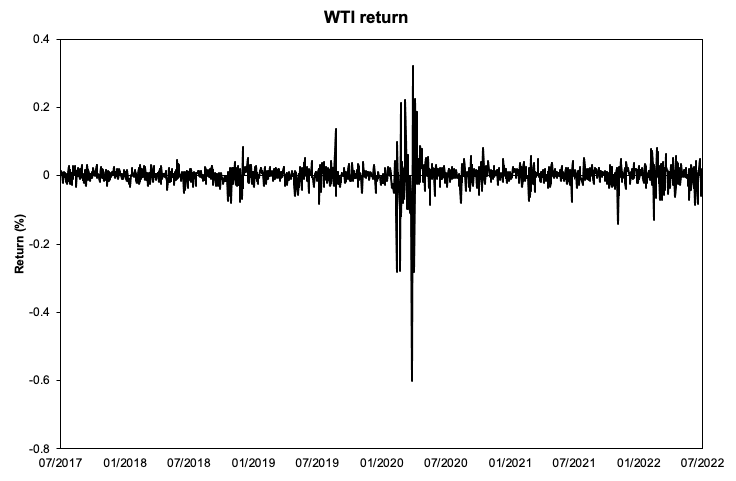

The concept of Brownian motion is associated with the contribution of Robert Brown (1828). More formally, the first works of Brown were used by the French mathematician Louis Bachelier (1900) applied to asset price forecast, which prepared the ground of modern quantitative finance. Price fluctuations observed over a short period, according to Bachelier’s theory, are independent of the current price as well as the historical behaviour of price movements. He deduced that the random behaviour of prices can be represented by a normal distribution by combining his assumptions with the Central Limit Theorem. This resulted in the development of the Random Walk Hypothesis, also known as the Random Walk Theory in modern finance. A random walk is a statistical phenomenon in which stock prices fluctuate at random. We implement a quantitative framework in a spreadsheet based on the Geometric Brownian Motion (GBM) model. Mathematically, we can derive the price of crude oil via the following model:

where dS represents the price change in continuous time dt, dX the Wiener process representing the random part, and Μdt the deterministic part.

The probability distribution function of the future price is a log-normal distribution when the price dynamics is described with a geometric Brownian motion.

Modelling crude oil market prices

Market prices

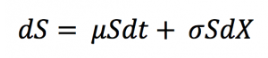

We downloaded a time series for WTI from June 2017 to June 2022. We picked this timeframe to assess the behavior of crude oil during two main market events that impacted its price: Covid-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine.

The two main parameters to compute in order to implement the model are the (historical) average return and the (historical) volatility. We eliminated outliers (the negative price of oil) to clean the dataset and obtain better results. The historical average return is 11.99% (annual return) and the historical volatility is 59.29%. Figure 1 helps to capture the behavior of the WTI price over the period from June 2017 to June 2022.

Figure 1. Crude oil (WTI) price.

Source: computation by the author (data: Refinitiv Eikon).

Market returns

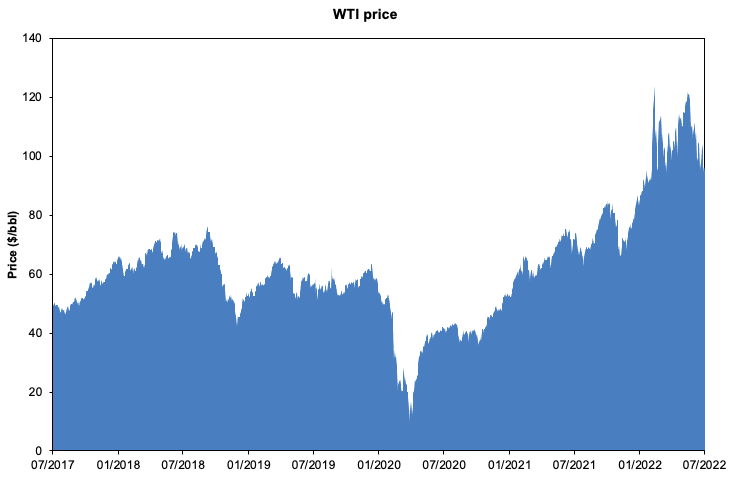

Figure 2 represents the returns of crude oil (WTI) over the period. We can clearly see that the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic had important implications for the negative returns in during the period covering early 2020.

Figure 2. Crude oil (WTI) return.

Source: computation by the author (data: Refinitiv Eikon).

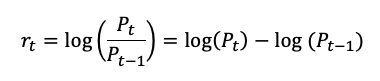

We compute the returns using the log returns approach.

where Pt represents the closing price at time t.

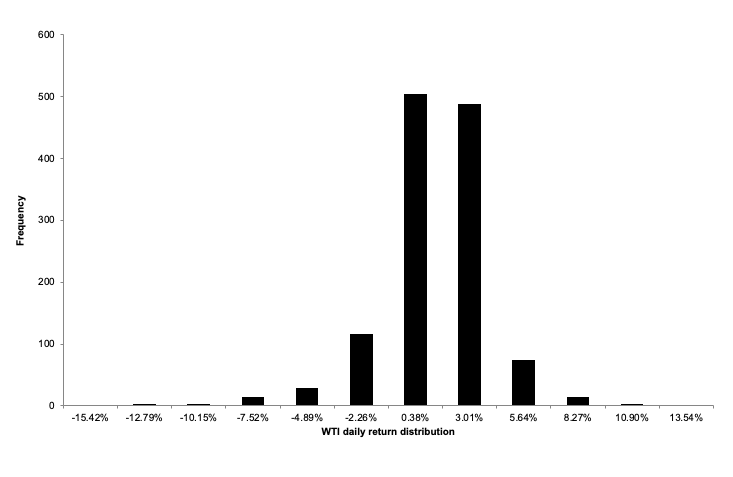

Figure 3 captures the distribution of the crude oil (WTI) daily returns in a histogram. As seen in the plot, the returns are skewed towards the negative tail of the distribution and show some peaks in the center of the distribution. When analyzed in conjunction, we can infer that the crude oil daily returns doesn’t follow the normal distribution.

Figure 3. Histogram of crude oil (WTI) daily returns. Source: computation by the author (data: Refinitiv Eikon).

Source: computation by the author (data: Refinitiv Eikon).

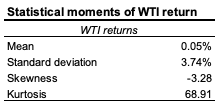

To have a better understanding of the crude oil behavior across the 1257 trading days retained for the period of analysis, it is interesting to run a statistical analysis of the four moments of the crude oil time series: the mean (average return), standard deviation (volatility), skewness (symmetry of the distribution), kurtosis (tail of the distribution). As captured by Table 1, crude oil performed positively over the period covered delivering a daily return equivalent to 0.05% (13.38% annualized return) for a daily degree of volatility equivalent to 3.74% (or 59.33% annualized). In terms of skewness, we can see that the distribution of crude oil return is highly negatively skewed, which implies that the negative tail of the distribution is longer than the right-hand tail (positive returns). Regarding the high positive kurtosis, we can conclude that the crude oil return distribution is more peaked with a narrow distribution around the center and show more tails than the normal distribution.

Table 1. Statistical moments of the crude oil (WTI) daily returns.

Source: computation by the author (data: Refinitiv Eikon).

Application: simulation of future prices for the crude oil market

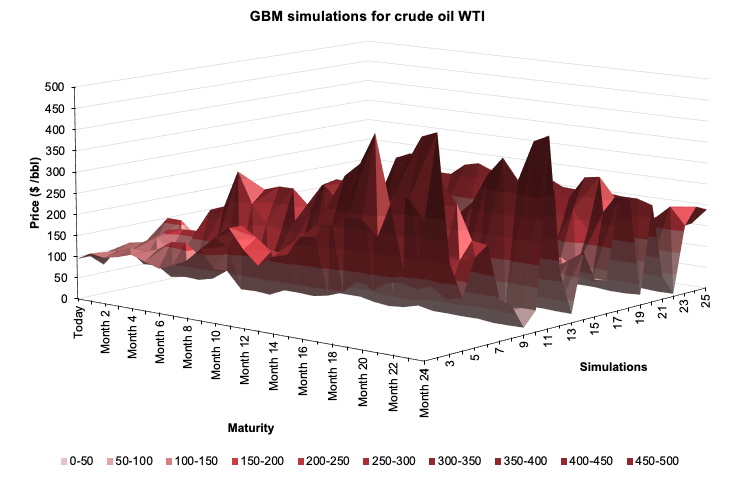

Understanding the evolution of the price of crude oil can be significant for pricing purposes. Some models (such as the Black-Scholes option pricing model) rely heavily on a price input and can be sensitive to this parameter. Therefore, accurate price estimation is at the core of important pricing models and thus having a good estimate of spot and future price can have a significant impact in the accuracy of the pricing implemented profitability of the trade.

We implement this framework and use a Monte Carlo simulation of 25 iterations to capture the different path that the WTI price can take over a period of 24 months. Figure 4 captures the result of the model. We plot the simulations in a 3D-graph to grasp the shape of the variations in each maturity. As seen from Figure 4, price peaked at the longer end of the maturity at a level near the 250$/bbl. Overall the shape is bumpy, with some local spikes achieved throughout the whole sample and across all the maturities (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Geometric Brownian Motion (GBM) simulations for WTI. Source: computation by the author (Data: Refinitiv Eikon).

Source: computation by the author (Data: Refinitiv Eikon).

You can find below the Excel spreadsheet that complements the explanations about of this article.

Related posts on the SimTrade blog

▶ Youssef LOURAOUI My experience as an Oil Analyst at an oil and energy trading company

▶ Jayati WALIA Brownian Motion in Finance

▶ Youssef LOURAOUI Introduction to Hedge Funds

▶ Youssef LOURAOUI Global macro strategy

▶ Youssef LOURAOUI Portfolio

Useful resources

Academic research

Bachelier, Louis (1900). Théorie de la Spéculation, Annales Scientifique de l’École Normale Supérieure, 3e série, tome 17, 21-86.

Bashiri Behmiri, Niaz and Pires Manso, José Ramos, Crude Oil Price Forecasting Techniques: A Comprehensive Review of Literature (June 6, 2013). SSRN Reseach Journal.

Brown, Robert (1828), “A brief account of microscopical observations made on the particles contained in the pollen of plants” in Philosophical Magazine 4:161-173.

About the author

The article was written in January 2023 by Youssef LOURAOUI (Bayes Business School, MSc. Energy, Trade & Finance, 2021-2022).