In this article, Bryan BOISLEVE (CentraleSupélec – ESSEC Business School, Data Science, 2023-2025) explains the Almgren-Chriss model, a fundamental framework in quantitative finance for optimal execution of large trading orders.

Introduction

Imagine you are a portfolio manager at a large asset management firm, and you need to sell 1 million shares of a stock. If you sell everything right now, you will significantly move the market price against yourself which comes with massive transaction costs. However, if you spread the trades over a too long a period, you expose yourself to the risk of adverse price movements due to market volatility. This dilemma between these two scenarios is one of the major optimal execution problems in finance.

The Almgren-Chriss model, developed by Robert Almgren and Neil Chriss in 2000, provides a mathematical framework to solve this problem. It has become an important model of algorithmic trading strategies used by investment banks, hedge funds, and asset managers worldwide. The model balances two competing objectives: minimizing transaction costs caused by market impact and minimizing the risk from price volatility during the execution period.

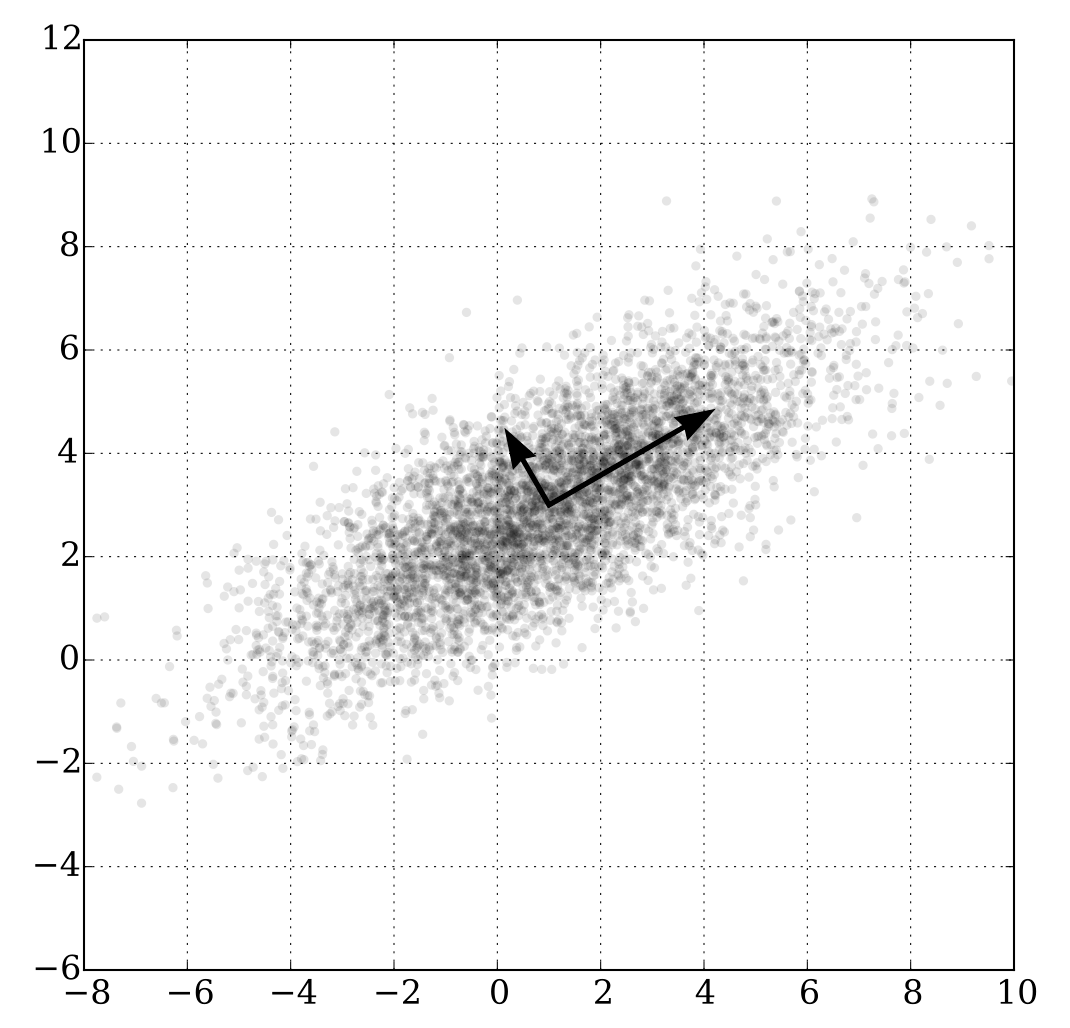

The liquidation trajectory after the use of Almgren-Chriss model

Source: Github (joshuapjacob)

The Core Problem: Market Impact and Execution Risk

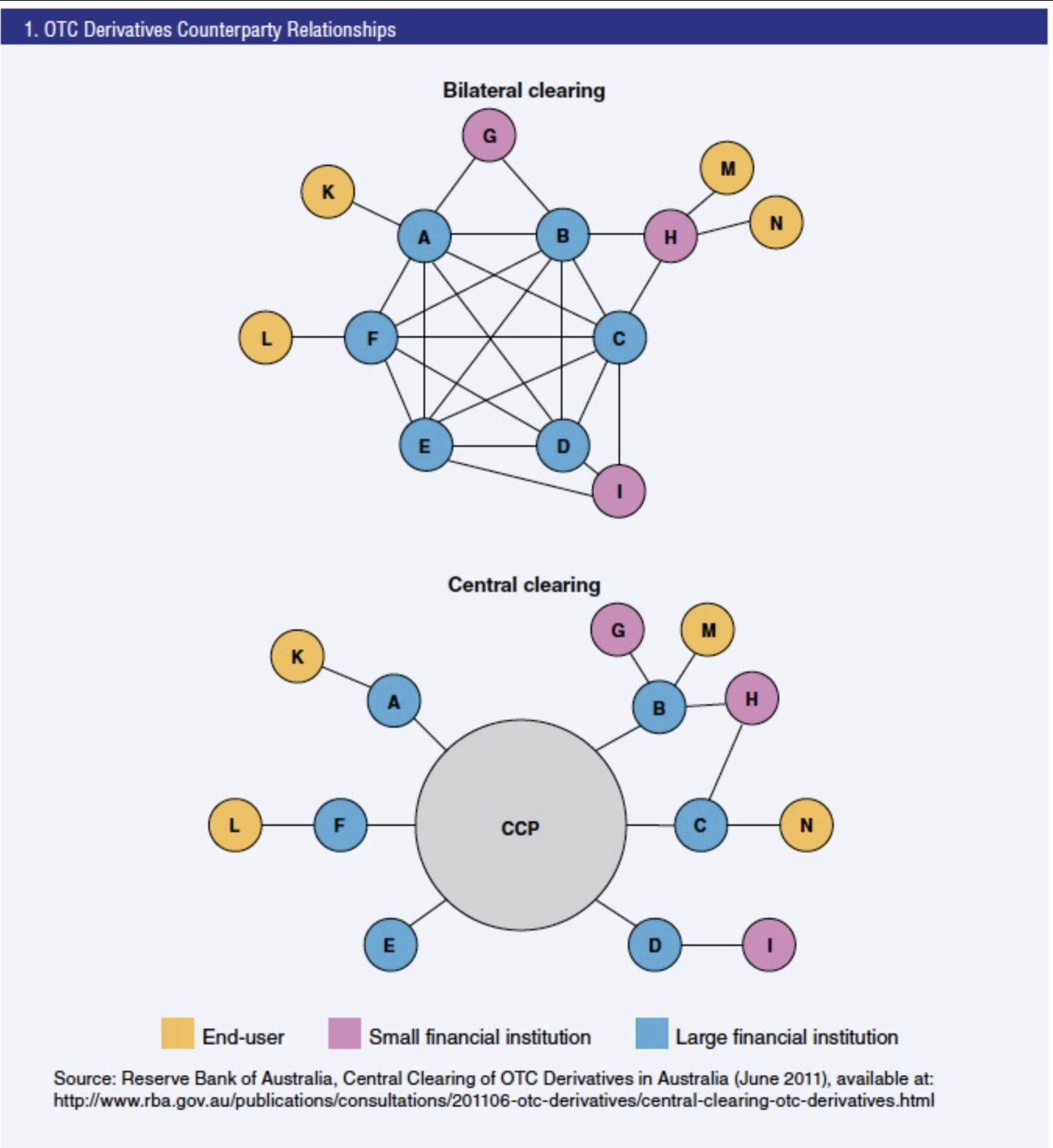

When institutional investors execute large orders, they face two types of market impact. The first is the permanent market impact which is the lasting changes in the equilibrium price caused by the information revealed through trading. For example, a large sell order might signal negative information about the stock, causing the price to drop permanently. The second impact is temporary market impact, which represents the immediate price concession required to find liquidity for the trade, which typically reverts after the order is completed.

In market microstructure, the canonical microfoundation for price impact is Kyle (1985). In Kyle’s model, an informed trader optimally splits a large order across time to hide private information, while competitive market makers update prices from the signed order flow. This generates a linear price impact: the price change is proportional to order flow, with the slope (Kyle’s lambda, λ) capturing how sensitive prices are to trading pressure. This provides a useful economic interpretation for the linear permanent-impact term in Almgren–Chriss: the “depth” parameter can be seen as an equilibrium measure of how quickly information get incorporated into prices, rather than as a purely statistical coefficient.

In addition to these costs, traders face execution risk or volatility risk, which is the uncertainty about future price movements while the order is being executed. A slow execution strategy minimizes market impact but increases exposure to this uncertainty, while rapid execution reduces volatility risk but amplifies market impact costs.

However, rather than assuming permanent impact persists indefinitely because of information content, Bouchaud (2009) shows that individual trade impacts follow a power-law decay governed by the market’s order flow dynamics and latent liquidity structure. The critical distinction is that this decay pattern emerges mechanically from how order books replenish and how traders split their orders across time, not because other participants are updating their valuations based on information signals.

The Mathematical Framework

The Almgren-Chriss model formulates optimal execution as a mean-variance optimization problem. Suppose we want to liquidate X shares over a time horizon T, divided into N discrete intervals. The model assumes that the stock price follows an arithmetic random walk with volatility, and our trading activity affects the price through both permanent and temporary impact functions.

Price Dynamics

The price evolves according to the discrete-time equation. At each step k, the mid-price moves because of an exogenous shock and the permanent impact of selling qk shares during [tk, tk+1]. The execution price also includes a temporary impact term that depends on v_k. The actual execution price we receive includes an additional temporary impact that depends on how quickly we are trading in that interval.

In the simplest linear case, the permanent impact is proportional to the number of shares we sell, with a coefficient representing the depth of the market. The temporary impact includes both a fixed cost (such as half the bid-ask spread) and a variable component proportional to our trading speed.

Expected Cost and Variance

The total expected cost of execution consists of three components: the permanent impact cost, the fixed cost proportional to the total shares traded, and the temporary impact cost that depends on how we split the order over time. Meanwhile, the variance of the trading cost is driven by price volatility and increases with the square of the inventory we hold at each point in time.

The optimization problem seeks to minimize a combination of expected cost and a risk-adjusted penalty for variance. A higher risk aversion parameter indicates greater concern about execution risk and leads to faster trading to reduce exposure.

The Optimal Strategy and Efficient Frontier

One of the most elegant results of the Almgren-Chriss model is the closed-form solution for the optimal trading trajectory. Under linear market impact assumptions, the optimal number of shares to hold at time t follows a hyperbolic sine function that decays from the initial position X to zero at the terminal time T.

The Half-Life of a Trade

A key insight from the model is the concept of the trade’s half-life, which represents the intrinsic time scale over which the position is naturally liquidated, independent of any externally imposed deadline T. This parameter is determined by the trader’s risk aversion, the stock’s volatility, and the temporary market impact coefficient.

If the required execution time T is much shorter than the half-life, the optimal strategy looks nearly linear which spreads trades evenly over time to minimize transaction costs. But, if T is much longer than the half-life, the trader will liquidate most of the position quickly to reduce volatility risk, with the trajectory looking as an immediate execution.

The Efficient Frontier

The Almgren-Chriss model produces an efficient frontier which is a curve in the space of expected cost versus variance where each point represents the minimum expected cost achievable for a given level of variance. This frontier is smooth and convex, as the efficient frontier in portfolio theory.

At one extreme lies the minimum-variance strategy (selling everything immediately), which has zero execution risk but very high transaction costs. At the other extreme is the minimum-cost strategy (the naive strategy of selling uniformly over time), which has the lowest expected costs but maximum exposure to volatility. The optimal strategy for any risk-averse trader lies somewhere along this frontier, determined by their risk aversion parameter.

Interestingly, the efficient frontier is differentiable at the minimum-cost point, meaning that one can achieve significant reductions in variance with only a marginal increase in expected cost. This mathematical property justifies moving away from the naive linear strategy toward more front-loaded execution schedules.

Practical Applications in Financial Markets

The Almgren-Chriss framework is behind many real-world algorithmic execution strategies used by institutional investors. VWAP (Volume-Weighted Average Price) strategies, which aim to execute trades in proportion to market trading volume, can be shown to be optimal for risk-neutral traders in certain extensions of the model. Also, TWAP (Time-Weighted Average Price) strategies, which execute at a constant rate over time, correspond to the minimum-cost solution when trading volume is constant.

Investment banks and electronic trading platforms use variations of the Almgren-Chriss model to power their execution algorithms. By calibrating the model parameters (volatility, market impact coefficients, risk aversion) to historical data and client preferences, these algorithms automatically determine the optimal trading schedule for large orders. The model also informs decisions about whether to use dark pools, limit orders, or aggressive market orders at different stages of the execution.

Beyond equity markets, the framework has been adapted to optimal execution in foreign exchange, fixed income, and derivatives markets, where liquidity conditions and market microstructure differ but the fundamental tradeoff between cost and risk remains central.

More broadly, the need for optimal execution fits naturally with Pedersen’s idea of markets being “efficiently inefficient”. Even when sophisticated investors detect mispricing or believe they have an informational edge, trading aggressively is limited by real frictions: transaction costs, market impact, funding constraints, and risk limits. These frictions imply that profit opportunities can persist because fully arbitraging them away would be too costly or too risky. From this perspective, Almgren–Chriss is not only a practical trading tool: it is a mechanism that quantifies one of the key forces behind “efficiently inefficient” markets, namely that the act of trading to exploit information or rebalance portfolios moves prices and creates costs that rationally slow down execution.

Why should I be interested in this post?

If you are a student interested in quantitative finance, algorithmic trading, or market microstructure, understanding the Almgren-Chriss model is essential. It represents an important application of stochastic optimization and control theory to real-world financial problems. By having a good understanding of this framework will prepare you for roles in proprietary trading, electronic market making, or quantitative research at investment banks and hedge funds.

Moreover, the model illustrates the broader principle of balancing multiple competing objectives under uncertainty which is a skill valuable across many areas of business and finance. The ability to formulate and solve such optimization problems is a key competency in quant finance.

Related Posts on the SimTrade Blog

▶ Raphael TRAEN Volume-Weighted Average Price (VWAP)

▶ Martin VAN DER BORGHT Market Making

▶ Jayati WALIA Implied Volatility

Useful Resources – Scientific articles

Almgren, R., & Chriss, N. (2000) Optimal execution of portfolio transactions Journal of Risk, 3(2), 5–39.

Almgren, R., & Chriss, N. (2001) Value under liquidation. Risk Journal of Mathematical Finance, 12(12), 61–63.

Bouchaud, J.-P. (2017) Price impact.

Bouchaud, J.-P., & Potters, M. (2003) Theory of financial risk and derivative pricing: From statistical physics to risk management Second Edition, Cambridge University Press.

Kyle, A. S. (1985) Continuous auctions and insider trading, Econometrica, 53(6), 1315–1335.

Kyle, A. S. (1989). Informed speculation with imperfect competition, Review of Economic Studies, 56(3), 317–355.

Useful Resources – Python code

Sébastien David, Arthur Bagourd, Mounah Bizri. Solving the Almgren-Chriss framework through dynamic programming

Sébastien David, Arthur Bagourd, Mounah Bizri. Solving the Almgren-Chriss framework through quadratic/nonlinear programming

About the Author

The article was written in December 2025 by Bryan BOISLEVE (CentraleSupélec – ESSEC Business School, Data Science, 2023-2025).

▶ Read all articles by Bryan BOISLEVE.