In this article, Saral BINDAL (Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur, Metallurgical and Materials Engineering, 2024-2028 & Research assistant at ESSEC Business School) explains how implied volatility is calculated or extracted from option prices using an option pricing model.

Introduction

In financial markets characterized by uncertainty, volatility is a fundamental factor shaping the pricing and dynamics of financial instruments. Implied volatility stands out as a key metric as a forward-looking measure that captures the market’s expectations of future price fluctuations, as reflected in current market prices of options.

The Black-Scholes-Merton model

In the early 1970s, Fischer Black and Myron Scholes jointly developed an option pricing formula, while Robert Merton, working in parallel and in close contact with them, provided an alternative and more general derivation of the same formula.

Together, their work produced what is now called the Black Scholes Merton (BSM) model, which revolutionized investing and led to the award of 1997 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel to Myron Scholes and Robert Merton “for a new method to determine the value of derivatives,” developed in close collaboration with the late Fischer Black.

The Black-Scholes-Merton model provides a theoretical framework for options pricing and catalyzed the growth of derivatives markets. It led to development of sophisticated trading strategies (hedging of options) that transformed risk management practices and financial markets.

The model is built on several key assumptions such as, the stock price follows a geometric Brownian motion with constant drift and volatility, no arbitrage opportunities, constant risk-free interest rate and options are European-style (options that can only be exercised at maturity).

Key Parameters

In the BSM model, there are five essential parameters to compute the theoretical value of a European-style option is calculated are:

- Strike price (K): fixed price specified in an option contract at which the option holder can buy (for a call) or sell (for a put) the underlying asset if the option is exercised.

- Time to expiration (T): time left until the option expires.

- Current underlying price (S0): the market price of underlying asset (commodities, precious metals like gold, currencies, bonds, etc.).

- Risk-free interest rate (r): the theoretical rate of return on an investment that is continuously compounded per annum.

- Volatility (σ): standard deviation of the returns of the underlying asset.

The strike price (exercise price) and time to expiration (maturity) correspond to characteristics of the option while the current underlying asset price, the risk-free interest rate, and volatility reflect market conditions.

Option payoff

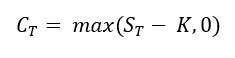

The payoff for a call option gives the value of the option at the moment it expires (T) and is given by the expression below:

Where CT is the call option value at expiration, ST the price of the underlying asset at expiration, and K is the strike price (exercise price) of the option.

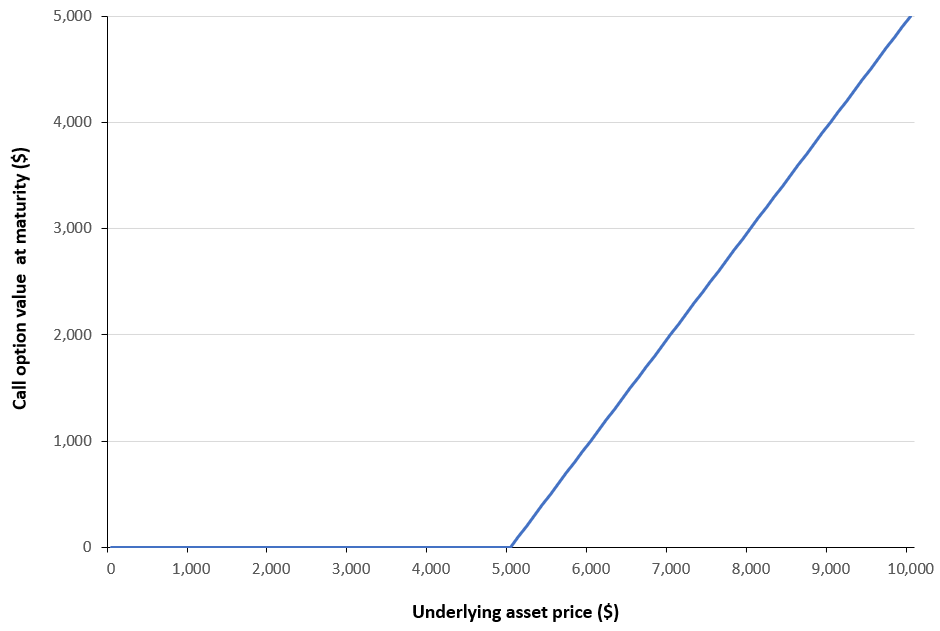

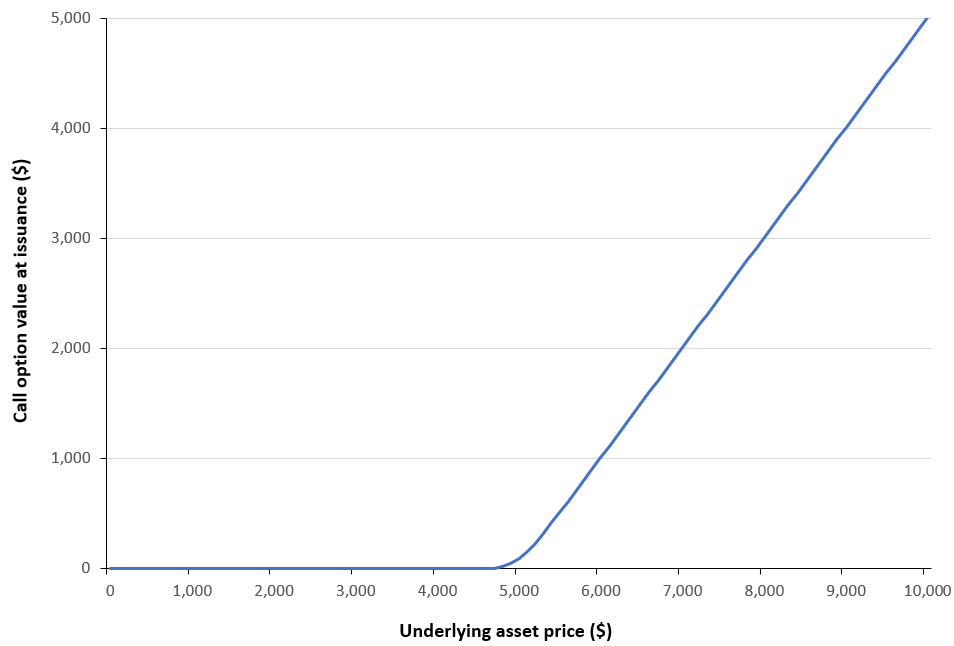

Figure 1 below illustrates the payoff function described above for a European-style call option. The example considers a European call written on the S&P 500 index, with a strike price of $5,000 and a time to maturity of 30 days.

Figure 1. Payoff value as a function of the underlying asset price.

Source: computation by the author.

Call option value

While the value of an option is known at maturity (being determined by its payoff function), its value at any earlier time prior to maturity, and in particular at issuance, is not directly observable. Consequently, a valuation model is required to determine the option’s price at those earlier dates.

The Black–Scholes–Merton model is formulated as a stochastic partial differential equation and the solution to the partial differential equation (PDE) gives the BSM formula for the value of the option.

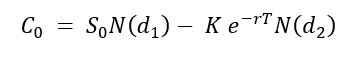

For a European-style call option, the call option value at issuance is given by the following formula:

with

Where the notations are as follows:

- C0= Call option value at issuance (time 0) based on the Black-Scholes-Merton model

- K = Strike price (exercise price)

- T = Time to expiration

- S0 = Current underlying price (time 0)

- r = Risk-free interest rate

- σ = Volatility of the underlying asset returns

- N(·) = Cumulative distribution function of the standard normal distribution

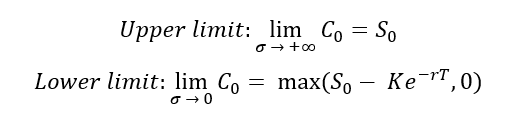

Figure 2 below illustrates the call option value as a function of the underlying asset price. The example considers a European call written on the S&P 500 index, with a strike price of $5,000 and a time to maturity of 30 days. The current price of the underlying index is $6,000, and the risk-free interest rate is set at 3.79% corresponding to the 1-month U.S. Treasury yield, and the volatility is assumed to be 15%.

Figure 2. Call option value as a function of the underlying asset price.

Source: computation by the author (BSM model).

Option and volatility

In the Black–Scholes–Merton model, the value of a European call or put option is a monotonically increasing function of volatility. Higher volatility increases the probability of finishing in-the-money while losses remain limited to the option premium, resulting in a strictly positive vega (the first derivative of the option value with respect to volatility) for both calls and puts.

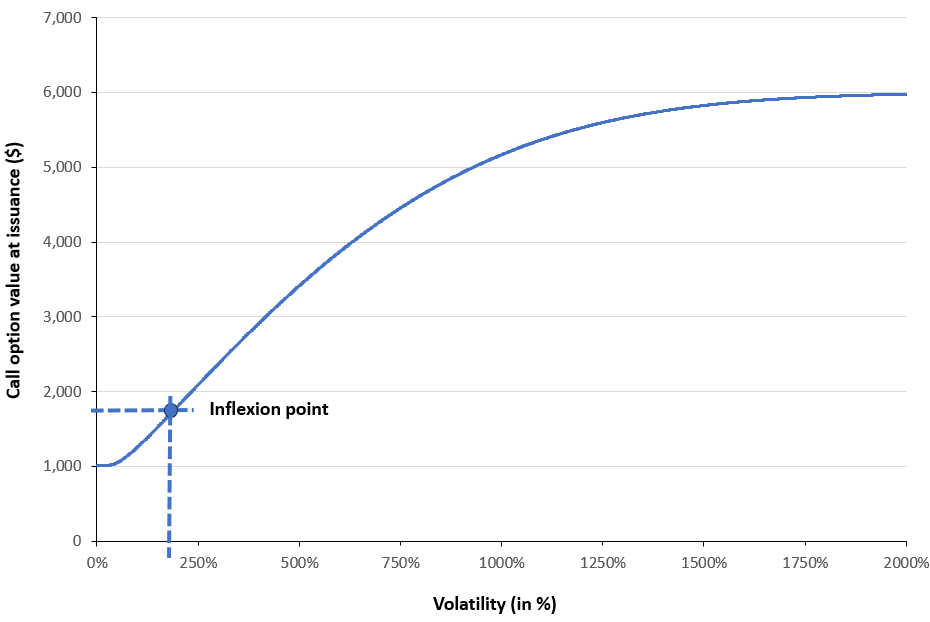

As volatility approaches zero, the option value converges to its intrinsic value, forming a lower bound. With increasing volatility, option values rise toward a finite upper bound equal to the underlying price for calls (and bounded by the strike for puts). An inflection point occurs where volga (the second derivative of the option value with respect to volatility) changes sign: at this point vega is maximized (at-the-money) and declines as the option becomes deep in- or out-of-the-money or as time to maturity decreases.

The upper limit and the lower limit for the call option value function is given below (Hull, 2015, Chapter 11).

Figure 3 below illustrates the value of a European call option as a function of the underlying asset’s price volatility. The example considers a European call written on the S&P 500 index, with a strike price of $5,000 and a time to maturity of 30 days. The current price of the underlying index is $6,000, and the risk-free interest rate is set at 3.79% corresponding to the 1-month U.S. Treasury yield. A deliberately wide (and economically unrealistic) range of volatility values is employed in order to highlight the theoretical limits of option prices: as volatility tends to infinity, the option value converges to an upper bound ($6,000 in our example), while as volatility approaches zero, the option value converges to a lower bound $1,015.51).

Figure 3. Call option value as a function of price volatility

Source: computation by the author (BSM model).

Volatility: the unobservable parameter of the model

When we think of options, the basic equation to remember is “Option = Volatility”. Unlike stocks or bonds, options are not primarily quoted in monetary units (dollars or euros), but rather in terms of implied volatility, expressed as a percentage.

Volatility is not directly observable in financial markets. It is an unobservable (latent) parameter of the pricing model, inferred endogenously from observed option prices through an inversion of the valuation formula given by the BSM model. As a result, option markets are best interpreted as markets for volatility rather than markets for prices.

Out of the five essential parameters of the Black-Scholes-Merton model listed above, the volatility parameter is the unobservable parameter as it is the future fluctuation in price of the underlying asset over the remaining life of the option from the time of observation. Since future volatility cannot be directly observed, practitioners use the inverse of the BSM model to estimate the market’s expectation of this volatility from option market prices, referred to as implied volatility.

Implied Volatility

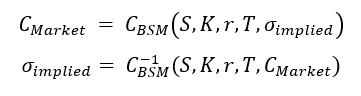

In practice, implied volatility is the volatility parameter that when input into the Black-Scholes-Merton formula yields the market price of the option and represents the market’s expectation of future volatility.

Calculating Implied volatility

The BSM model maps five input variables (S, K, r, T, σimplied) to a single output variable uniquely: the call option value (Price), such that it’s a bijective function. When the market call option price (CBSM) is known, we invert this relationship using (S, K, r, T, CBSM) as inputs to solve for the implied volatility, σimplied.

Newton-Raphson Method

As there is no closed form solution to calculate implied volatility from the market price, we need a numerical method such as the Newton–Raphson method to compute it. This involves finding the volatility for which the Black–Scholes–Merton option value CBSM equals the observed market option price CMarket.

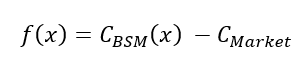

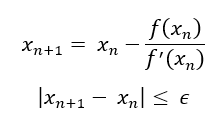

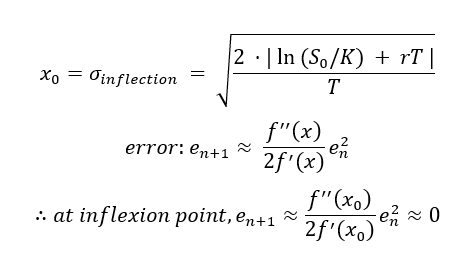

We define the function f as the difference between the call option value given by the BSM model and the observed market price of the call option:

Where x represents the unknown variable (implied volatility) to find and CMarket is considered as a constant in the Newton–Raphson method.

Using the Newton-Raphson method, we can iteratively estimate the root of the function, until the difference between two consecutive estimations is less than the tolerance level (ε).

In practice, the inflexion point (Tankov, 2006) is taken as the initial guess, because the function f(x) is monotonic, so for very large or very small initial values, the derivative becomes extremely small (see Figure 3), causing the Newton–Raphson update step to overshoot the root and potentially diverge. Selecting the inflection point also minimizes approximation error, as the second derivative of the function at this point is approximately zero, while the first derivative remains non-zero.

Where σinflection is the volatility at the inflection point.

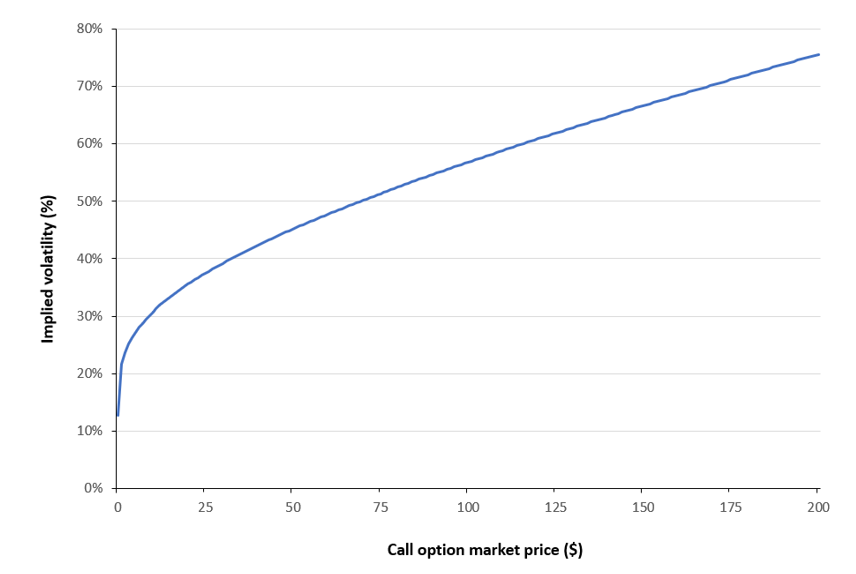

Figure 4 below illustrates how implied volatility varies with the call option price for different values of the market price (computed using the Newton–Raphson method). As before, the example considers a European call written on the S&P 500 index, with a strike price of $5,000 and a time to maturity of 30 days. The current level of the underlying index is $6,000, and the risk-free interest rate is set at 3.79% corresponding to the 1-month U.S. Treasury yield.

Figure 4. Implied volatility vs. Call Option value

Source: computation by the author.

You can download the Excel file provided below, which contains the calculations and charts illustrating the payoff function, the option price as a function of the underlying asset’s price, the option price as a function of volatility, and the implied volatility as a function of the option price.

You can download the Python code provided below, to calculate the price of a European-style call or put option and calculate the implied volatility from the option market price (BSM model). The Python code uses several libraries.

Alternatively, you can download the R code below with the same functionality as in the Python file.

Why should I be interested in this post?

The seminal Black–Scholes–Merton model was originally developed to price European options. Over time, it has been extended to accommodate a wide range of derivatives, including those based on currencies, commodities, and dividend-paying stocks. As a result, the model is of fundamental importance for anyone seeking to understand the derivatives market and to compute implied volatility as a measure of risk.

Related posts on the SimTrade blog

▶ Akshit GUPTA Options

▶ Jayati WALIA Black-Scholes-Merton Option Pricing Model

▶ Jayati WALIA Implied Volatility

▶ Akshit GUPTA Option Greeks – Vega

Useful resources

Academic research

Black F. and M. Scholes (1973) The pricing of options and corporate liabilities. Journal of Political Economy, 81(3), 637–654.

Merton R.C. (1973) Theory of rational option pricing. The Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science, 4(1), 141–183.

Hull J.C. (2022) Options, Futures, and Other Derivatives, 11th Global Edition, Chapter 15 – The Black–Scholes–Merton model, 338–365.

Cox J.C. and M. Rubinstein (1985) Options Markets, First Edition, Chapter 5 – An Exact Option Pricing Formula, 165-252.

Tankov P. (2006) Calibration de Modèles et Couverture de Produits Dérivés (Model calibration and derivatives hedging), Working Paper, Université Paris-Diderot. Available at https://cel.hal.science/cel-00664993/document.

About the BSM model

The Nobel Prize Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 1997

Harvard Business School Option Pricing in Theory & Practice: The Nobel Prize Research of Robert C. Merton

Other

NYU Stern Volatility Lab Volatility analysis documentation.

About the author

The article was written in December 2025 by Saral BINDAL (Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur, Metallurgical and Materials Engineering, 2024-2028 & Research assistant at ESSEC Business School).

▶ Discover all articles written by Saral BINDAL