In this article, Hadrien PUCHE (ESSEC Business School, Grande École Program, Master in Management, 2023-2027) comments on Jesse Livermore’s timeless quote and explores its relevance for modern investors and students seeking to understand market psychology.

About Jesse Livermore

Jesse Livermore (1877–1940) was one of Wall Street’s first great speculators, a man who understood the rhythm of markets long before data screens and algorithms existed. He made and lost several fortunes, most famously by shorting stocks ahead of the Panic of 1907 and the Great Depression of 1929.

Livermore’s life was both brilliant and tragic, but his insights into crowd behavior and emotional discipline remain essential reading for anyone who wishes to understand how markets truly work.

Jesse Livermore

Analysis of the quote

“The market is never wrong, only opinions are.” – Jesse Livermore

When Livermore says, “The market is never wrong, only opinions are,” he reminds us that prices are not moral judgments or forecasts of truth — they are the product of human behavior under uncertainty.

Markets do not care about fairness or logic. They reflect the collective sum of all opinions, weighted by money. To claim that “the market is wrong” is to claim that your personal view outweighs the collective intelligence and capital of millions of other participants.

That rarely ends well. The market may sometimes overreact, but it is almost always the individual who misunderstands its message.

This quote, in the end, is a lesson in humility. Investors lose not because they lack intelligence, but because they refuse to admit when the market has proven them wrong.

Economic and financial concepts related to the quote

1 – Market efficiency

Livermore’s idea anticipates the theory of market efficiency introduced many decades later by Eugene Fama in 1970. This theory suggests that prices incorporate all available information, which means it is almost impossible to consistently beat the market.

Even if markets are not perfectly efficient, they are highly competitive ecosystems. Information spreads very quickly, and any mispricing is soon corrected by professionals equipped with technology and capital.

So when you decide that the market is wrong, you are effectively betting that your insight is sharper than everyone else’s, from hedge funds to central banks. Occasionally, some investors do have that edge, but they are the exception, not the rule.

2 – The Wisdom and the Madness of Crowds

In The Wisdom of Crowds (2004), James Surowiecki argues that large groups can make remarkably accurate collective judgments, even when individual members are biased or imperfectly informed. Financial markets often exemplify this phenomenon: while single investors are prone to emotion and error, the aggregation of their independent views can produce a consensus that efficiently reflects available information.

Yet, Surowiecki also cautions that collective intelligence breaks down when independence disappears. In markets, this occurs when participants are driven by shared emotions: panic during crashes or euphoria during bubbles. At such moments, the “wisdom” of the crowd can turn to madness.

3 – Risk management and flexibility

Livermore’s warning remains as relevant as ever: never fight the market. Every investor is wrong sometimes, but what matters is how quickly you realize it and act. The real danger isn’t being wrong, it’s refusing to admit it. Livermore’s rule captures this perfectly: “Cut your losses short and let your winners run.”

Good risk management starts there. It means knowing how much you can afford to lose, setting a stop-loss before entering a trade, and sticking to it. A stop-loss isn’t a sign of weakness, it’s a protection. It prevents small mistakes from turning into big ones and keeps you in the game for the long run.

As Keynes famously said, “Markets can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent.” Managing risk isn’t about predicting the market, it’s about surviving it.

My opinion about this quote

Livermore’s insight feels even more relevant in today’s world of instant information and algorithmic trading. Social media multiplies opinions at unprecedented speed, creating noise that can easily obscure reality.

Recent market episodes illustrate this perfectly. In 2021, for example, the GameStop saga showed how collective emotion on Reddit briefly overwhelmed fundamental analysis, sending the stock to irrational highs before gravity reasserted itself.

Similarly, during the cryptocurrency boom of 2021 and 2022, investors often claimed that “this time is different,” only to face sharp corrections when enthusiasm faded.

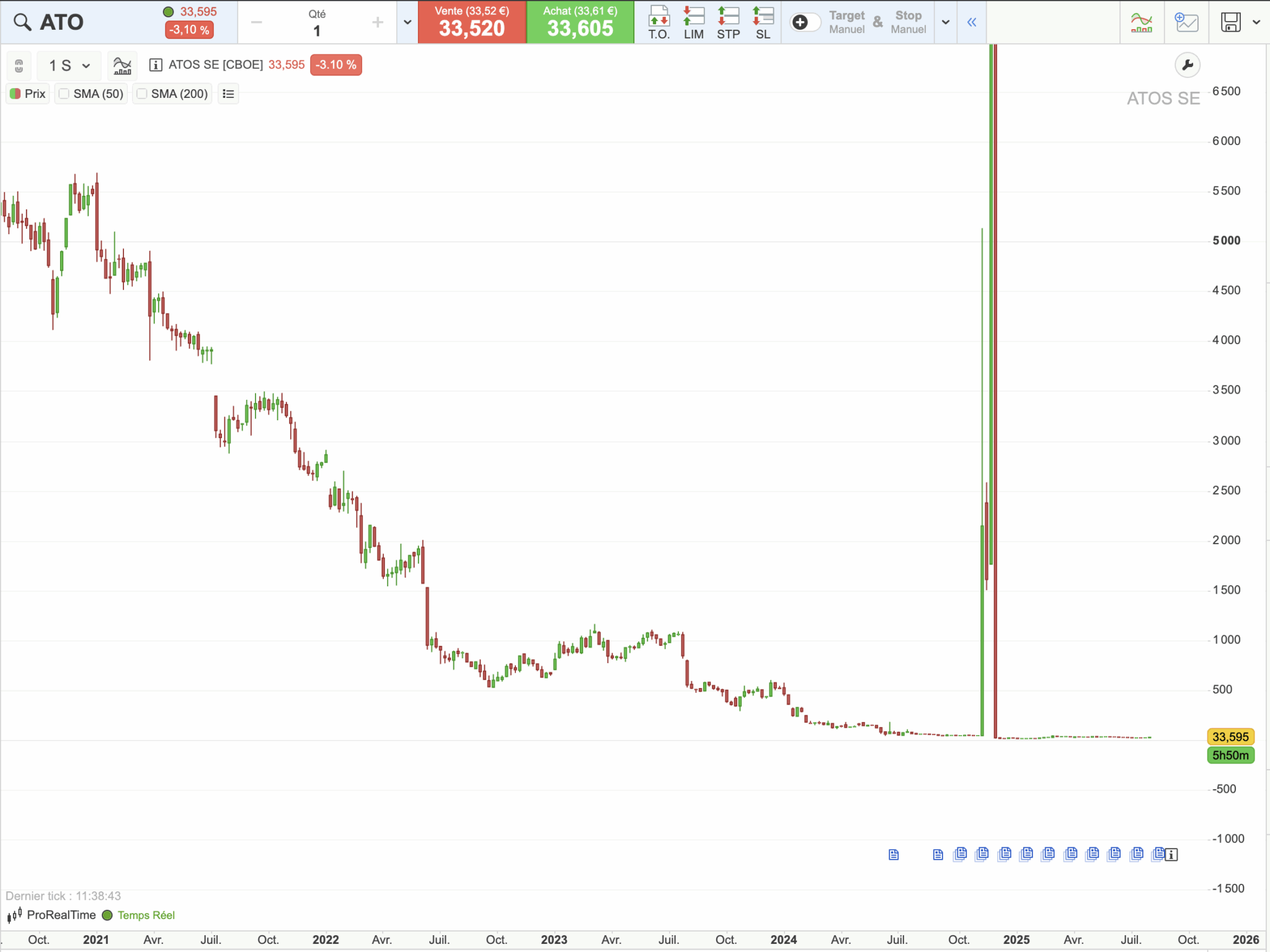

Closer to home, the Atos case in 2024 reflected the same dynamic. Despite the company’s severe financial distress and an announced dilution that effectively made the stock almost worthless, waves of speculative buying pushed its valuation to absurd levels for a few days. When reality returned, the correction was brutal.

These examples confirm Livermore’s message: opinions can be wrong for a long time, but the market always has the final word.

Why should you be interested in this post?

For students and young professionals, Livermore’s lesson is a call for intellectual humility. Markets are complex and adaptive systems, impossible to predict with precision but possible to understand with patience.

Learning to separate your opinions from what the market is telling you will make you a better analyst, investor, and decision-maker. It will also help you develop emotional intelligence, a skill far rarer than technical knowledge.

In finance, as in life, the goal is not to be right, it is to adapt faster when you are wrong.

Related posts on the SimTrade blog

Useful resources

Reminiscences of a Stock Operator – Edwin Lefèvre (1923)

The Efficient Market Hypothesis and Its Critics – Burton Malkiel (2003)

Thinking, Fast and Slow – Daniel Kahneman (2011)

SimTrade course Market information

Academic research

Fama E. (1970) Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work, Journal of Finance, 25, 383–417.

Fama E. (1991) Efficient Capital Markets: II, Journal of Finance, 46, 1575–617.

Grossman S.J. and J.E. Stiglitz (1980) On the Impossibility of Informationally Efficient Markets, The American Economic Review, 70, 393–408.

Chicago Booth Review (30/06/2016) Are markets efficient? Debate between Eugene Fama and Richard Thaler (YouTube video)

About the author

This article was written in November 2025 by Hadrien PUCHE (ESSEC, Grande École Program, Master in Management – 2023–2027).