There are two primary approaches to investing in the stock market. Some market participants adopt a trading-oriented strategy; they believe that financial gains depend on their ability to predict the evolution of the market (when to enter and when to exit), or in other words, they try to time the market. Other market participants favor a long-term investment approach: they expect their investments to compound over 10 or 20 years, by spending as much time in the market.

Time in the market vs. timing the market is a classic debate in the investment world. Kenneth Fisher had a very strong opinion on this debate. To him, “Time in the market beats timing the market”. The duration on an investment (the time in the market) is a significantly better factor of success for your investments that the quality of your attempts to optimize entry and exit points (timing the market).

For the vast majority of market participants, the effort to outmaneuver daily fluctuations is not just difficult, but a statistically losing game.

In this article, Hadrien PUCHE (ESSEC, Grande École Program, Master in Management, 2023-2027) explores the behavioral and financial foundations of Fisher’s principle, analyzing why the “cost of being out” can often exceed the risks of staying in through market cycles.

About Kenneth Fisher and the quote

Source: Fisher Investments

Source: Fisher Investments

Kenneth Fisher is a billionaire investment analyst, who founded Fisher Investments. He also is a long-time columnist for Forbes. He is well known for his contributions to investment theory, particularly in popularizing the use of the Price-to-Sales ratio. Throughout his career, Fisher has been a vocal critic of the “market timing” fallacy, arguing that most investors hurt their returns by trying to avoid downturns.

This quotes originates from a 2018 USA Today article where Kenneth Fisher wrote :

“Even the greatest investors are wrong maybe a third of the time. But here’s some good news: You don’t need perfect timing to achieve marvelous returns. Time in the market beats timing the market – almost always.”

Analysis of the quote

The fundamental question every investor face is: How to invest? While the allure of “buying low and selling high” sounds simple, executing it consistently is nearly impossible. Fisher’s quote highlights that the market is not a puzzle to be solved daily, but a vehicle to be ridden over years.

“Timing the market” requires two perfect decisions: knowing exactly when to get out and exactly when to get back in. “Time in the market,” conversely, requires only one decision: to start. By staying invested, you capture the total return of the market, including dividends and the recovery phases that follow volatility. Fisher’s principle suggests that the “missed opportunity” of being on the sidelines is the greatest risk of all.

Furthermore, Fisher’s insight also implies that an investment’s duration is very often more important than the yield. Too many investors are obsessed over finding the best “alpha” (a few extra percentage points of return) but forget about duration. A moderate return sustained over decades will always outperform a spectacular return that gets interrupted all the time.

Similarly, another thing to consider is the heavy “cost of inaction” that comes with searching for the perfect entry point. By waiting for the ideal market conditions or trying to identify the absolute best opportunities, you are losing time (and therefore compounding); a cost that is rarely justified by the improved entry point.

Three Financial Concepts Linked to the Quote

We now introduce three financial concepts that are related to this quote, and that you may find useful to understand the mechanics behind Fisher’s principle: the long-term drivers of the market growth, the danger of missing the “Best Days”, and the Dollar Cost Averaging (DCA) to find a good compromise between timing and time.

The long-term drivers of the market growth

To understand why “time in the market” works, we have to look at what actually drives the market’s long-term upward trajectory. Unlike a casino, the stock market is a vehicle for productive capital, and its growth is fueled by fundamental economic forces:

- GDP Growth & Corporate Earnings: As the global economy expands and companies become more efficient, they generate higher profits. Over decades, stock prices tend to track this fundamental growth in value.

- Inflation: Since stocks represent ownership in real assets and businesses, they act as a natural hedge. As prices for goods and services rise, nominal corporate revenues and asset values follow suit.

- The Equity Risk Premium: This is the “extra” return investors demand for choosing stocks over “risk-free” assets like government bonds. To earn this premium, you simply have to be present.

By staying in the market, you aren’t just “hoping” for a rise; you are capturing the compounding effect of global productivity and inflation.

The danger of missing the “Best Days”

When it comes to the statistical distribution of the market returns, it is important to understand that it is highly skewed, with the bulk of annual gains often concentrated in a handful of trading sessions. This concentration creates a massive “cost of being out” for any investor that happens to miss such days.

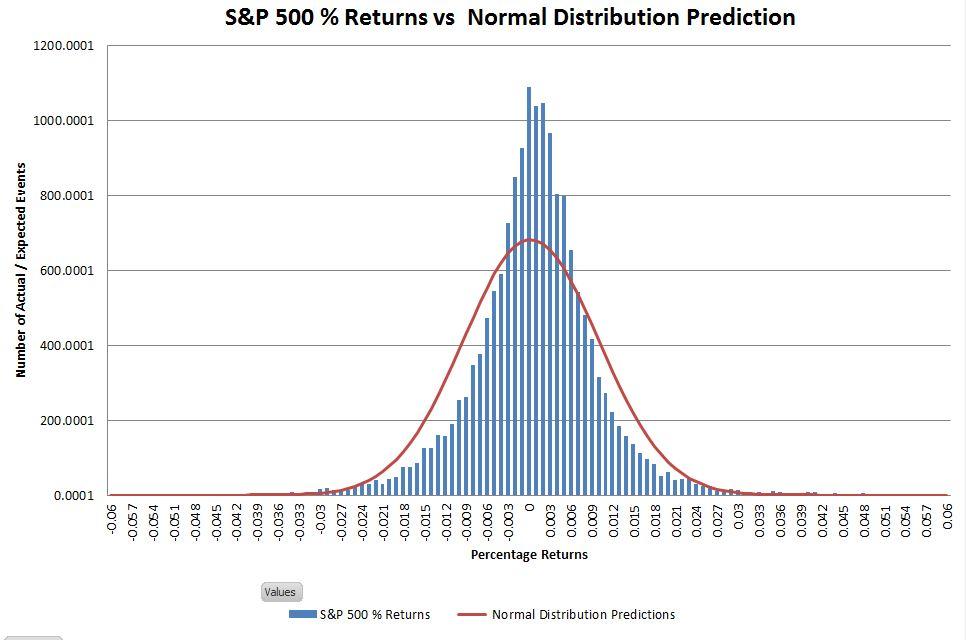

The figure below shows the distribution of the returns on the S&P 500 index compared to the estimated normal distribution. What matters here is that the S&P500 distribution has much fatter tails than the normal ones; meaning that very high and very low returns happen more than one would expect with a normal distribution.

Figure 1. Distribution of the returns on the S&P 500 index

Source: Seeking Alpha

The issue with these fatter tails is that missing a small number of high-returns days can be catastrophic for an investor’s terminal wealth. Historically, missing just the 10 best days in a decade is enough to cut an investor’s total return by half, and missing the best 30 days end can turn the returns negative, even in a bull market.

The paradox of the “Time in the Market” is that these “best days” usually occur within weeks or days of the “worst days.” By trying to avoid the worst days, many also miss the best days, and this is where the true opportunity cost lies. The only proven way to make sure that you are present for the best days is to stay invested through the worst ones

DCA: The Compromise Between Timing and Time

Let’s say you have €10,000 today, and you want to invest them in the market. You do not want to “time the market” and want instead to spend “time in the market”. However, you are facing the “entry dilemma”: should you go all-in now or wait for a better price in a few days?

Going all-in (Lump Sum investing) means immediate exposure, but it can make many investors uncomfortable. To make it easier and more manageable, many investors choose to rather do a Dollar Cost Averaging (DCA): investing their money progressively at set intervals (monthly, weekly, etc.).

The DCA approach is psychologically attractive, because it removes the paralysis that comes with the fear of “buying the top.” If the market drops the day after your first investment, you actually benefit by buying the next “tranche” at a lower price. However, financial literature suggests a different reality.

Most academic research, including the study by Brennan, Li, and Torous (2005), argues that Lump Sum investing outperforms DCA roughly 75% of the time. This is because markets have a positive “expected return” (they go up more often than they go down). By holding cash on the sidelines to “average in,” you are essentially betting against the market’s natural upward trajectory.

Brennan’s core argument is that “Dollar-Cost Averaging just means taking risk later.” By choosing DCA, you aren’t avoiding market risk; you are simply delaying your full participation in the market’s growth. The “cost” of this delay is often higher than the benefit of potentially catching a lower entry price.

So why do so many professionals still recommend DCA?

The choice is ultimately a psychological one. While a Lump Sum is mathematically superior, it carries a high “regret risk.” If an investor puts €10,000 in on Monday and the market crashes on Tuesday, they might panic and sell everything, violating Fisher’s principle of staying in the market. DCA acts as a behavioral bridge: it may yield slightly lower returns on average, but it ensures the investor actually stays the course.

Ultimately, the “best” strategy is the one that prevents you from exiting the market prematurely. How much stress do you feel at the idea of a short-term loss? If that stress leads to bad decisions, the “insurance” provided by DCA is well worth the mathematical trade-off.

Why you should always keep this quote in mind

Fisher’s perspective extends far beyond financial advice. It is a reminder that in most cases, in both your personal and professional life, consistency matters more than intensity. While the modern world often rewards the pursuit of the “perfect” moment, this mantra suggests that the duration of your efforts is a far more reliable predictor of success than the timing of your actions.

At its core, this quote is a reminder that time will always be your greatest asset. You may not always secure the highest yields, or the most prestigious returns in the short term, but as long as you maintain a longer presence, the cumulative effect of being active will eventually outweigh the benefits of a single, well-timed move.

Consider your own professional career. As a student, your immediate returns may not be that great, and you may fail at “timing the market” by not landing the perfect role in the perfect company in your first attempt. But as long as you spend more “time in the market” (by building skills, networking, gaining experience…), you will eventually reach your objectives.

There is also a significant (and often overlooked) cost to trying too hard to find the perfect opportunities. When you obsess over timing, you risk analysis paralysis and the exhaustion of your mental capital. Sometimes the most strategic move is to accept the path currently before you, proceed with discipline, and allow the future to unfold. By focusing on your tenure rather than your timing, you trade the stress of the unknown for the certainty of cumulative growth.

In the long run, the most successful individuals are rarely those who waited for the wind to be perfect; they are those who kept their sails up regardless of the weather. By internalizing this quote, you adopt a mindset that values patience as a form of hidden strength, ensuring that your capital (both financial and intellectual) has the necessary room to breathe, and expand.

Related Posts on the SimTrade Blog

▶ Hadrien PUCHE “The stock market is designed to transfer money from the impatient to the patient” – Warren Buffett

▶ Hadrien PUCHE “Price is what you pay, value is what you get” – Warren Buffett

Useful resources

Fisher Investments Market Commentary. Insights from Ken Fisher’s firm on why staying the course matters.

Academic literature

Fama E.F. (1965) Random Walks in Stock Market Prices, Financial Analysts Journal, 21(5), 55-59.

Brinson G.P., L.R. Hood, and G.L. Beebower (1986) Determinants of Portfolio Performance, Financial Analysts Journal, 42(4), 39-44.

Brennan M.J., F. Li, and W.N. Torous (2005) Dollar-Cost Averaging Just Means Taking Risk Later, Review of Finance, 9(4), 509–535.

About the Author

This article was written in February 2026 by Hadrien PUCHE (ESSEC Business School, Grande École Program, Master in Management, 2023-2027).

▶ Discover all articles by Hadrien PUCHE