In this article, William LONGIN (Sorbonne School of Economics, Master in Money Banking Finance Insurance, 2024-2026) discusses the religious imagery in finance contained in the book ‘Money’ (L’Argent) by Émile Zola.

L’Argent

Published in 1891, L’Argent (Money) is a book written by Émile Zola a 19th-century French novelist and journalist, known for founding the naturalist literary movement and for his bold defense of justice in the Dreyfus Affair. The book ‘Money’ tells the story of Aristide Saccard, a Parisian banker whose risky projects lead to a boom and a crash of his bank called “The Universal Bank” on the Paris Stock Exchange. By using biblical references, metaphors of faith, and symbolism, the author shows how wealth is deeply intertwined with religion at the time of the Second Empire in France (1852-1870). Throughout the novel, the author conceptualizes “faith” as a value-generating mechanism, as shown by religious symbolism within financial institutions.

First edition of L’Argent by Émile Zola (1891).

Source: Bibilothèque Charpentier (Paris).

Faith creates value

In financial markets the law of supply and demand is what drives prices. The demand is driven by what market participants think an asset will bring back in terms of cash flows in the future. This is seen with the word “credit” that comes from the Latin word “credo” showing how belief is central in finance. This belief is uncertain and ungraspable as financial markets can be similar to the omnipotence of God. Zola illustrates this comparison by mixing liturgic elements with finance. In chapter 10 of the book, traders have blind faith in the markets ability to deliver and produce “miracles”. Zola compares stock-market belief with an irrational religion, blind to the signs of a crash.

“…the faithful believed in a rise as they believed in the good Lord.” (chapter 10)

In the General Theory of Keynes, markets are described as being influenced by “animal spirits” through instincts, moods, and confidence that drive people to invest or hold back, rather than pure logic. Similarly, Émile Zola adds a religious dimension to Keynes argument as the characters believe in financial miracles, almost presenting the stock market as the center of a religion of its own.

“…he searched to know by what fault God had not allowed him to bring to fruition the great Catholic bank destined to transform modern society, that treasure of the Holy Sepulchre which would restore a kingdom to the Pope…” (chapter 12)

The main character, Saccard, blames God rather than his own actions, evading moral responsibility for how he handled his clients’ money and shifting guilt onto a higher power. The “sacralized” project of the Universal bank tied to the Holy Sepulchre and the papacy pushes the project as a catholic investment. By intertwining the Holy Sepulchre’s “treasure” with banking, Zola blurs the line between crusade and commerce.

Banks and stock exchanges: religious buildings

Throughout the book the stock market is compared to a church. In the first chapter a comparison of the staircase of the stock exchange is made comparing the level of usage of the stairs saying the they were “more worn than the thresholds of old churches.” The stock exchange is later described “as a four-pointed star”. Zola ironically sacralizes the trading pit (la corbeille in French) comparing it to a modern temple where people worship capital.

Paris Stock Exchange building: Palais Brongniart in the 19th century.

Source: Bourse de Paris archives.

La corbeille in the Paris Stock Exchange.

Source: Bourse de Paris archives.

Zola hints that modern hubris is architectural. In chapter 5, the board room of the Universal Bank is compared to a “chapel”. And later on, in chapter 8, the Universal Bank’s headquarters turns into a temple, “part temple, part café-concert”. Zola uses liturgical vocabulary to show the sacralization of finance. Through décor, ritual, and titles, the bank borrows sacred codes of respectability and vice versa, the church becomes a place to pray for gains and a better future. This logic is echoed in the construction of the J.P. Morgan building at 23 Wall Street in New York, whose early-twentieth-century, temple-like mass of stone, stripped of ornament and pierced by only a few windows, presents the bank as an inviolable shrine to capital, a solid and reassuring “sanctuary” for investors’ money. Like Zola’s Universal Bank, such architecture turns finance into a quasi-religious experience: a teller’s counter that resembles an altar or chapel is reassuring for its depositors.

People in finance

Zola presents leading financiers as disciplined to the point of asceticism (a way of living that deliberately avoids physical comforts and pleasures). The character of Gundermann is a powerful Jewish banker who embodies cold, rational, and stable finance serving as Saccard’s rival and the realistic counterpoint to his reckless speculation. He lives “a galley-slave life,” suggesting monk-like self-denial but at the same time living in a luxurious environment. His rapport to money is religious as seen in chapter 5, money is handled with “clerical discretion”.

Another striking aspect of L’Argent is the way Zola shows winners on the market being treated almost like superior beings. Successful financiers are not just clever speculators; they are revered as if they possessed a special, mystical intelligence. Early in the novel, Gundermann is described as an object of worship, with “crowds prostrated around the god” (chapter 1).

Portraits at the Paris Bourse

Source: Edgard Degas.

Saccard, too, embraces this quasi-divine status. He casts himself as a savior of society rather than a mere businessman. “We are here to save everything,” he proclaims (chapter 5), boldly taking over the Church’s traditional mission of redemption and applying it to financial speculation. Zola reinforces this confusion of sacred and economic power through moments of visionary revelation through the idea of “The Universal Bank” appears to Saccard “as if in letters of fire,” as though granted by some higher power rather than born of greed and ambition. In this way, Zola suggests that modern capitalism creates its own gods, prophets, and miracles, transforming financial success into a new form of worship.

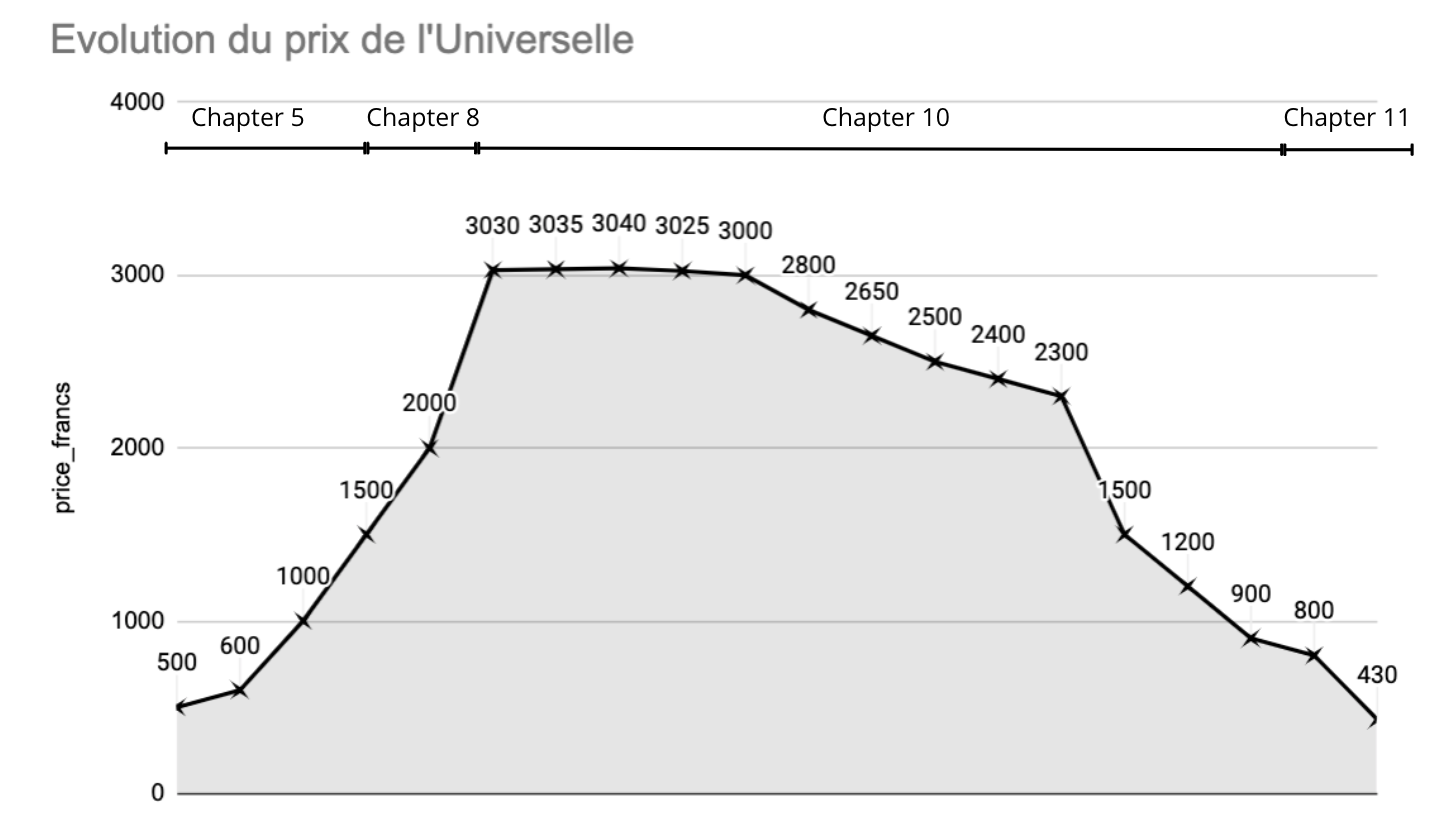

The figure below depicts the stock price trajectory of “The Universal Bank” as presented in the book. The horizontal axis reflects time, structured according to the chapters providing information on price movements, since Zola does not specify explicit calendar dates.

Evolution of the stock price of The Universal Bank shares.

Source: the author.

“What about today”

Today’s western civilization is much less religious than before with about only 50% of the French population claiming to believe in a religion where as it was once a majority during Émile Zola’s time. While Catholic credit unions once existed, Christian finance has mostly been replaced by ESG investing. The 2015 launch of the S&P 500 Catholic Values Index sparked some attention, but French banks rarely use religious symbolism.

In contrast, the U.S. has a well-developed Christian finance market. Firms like Knights of Columbus and Timothy Plan openly market faith-based portfolios aligned with biblical principles, often referencing scripture and using religious imagery. Products screen out morally objectionable sectors and promote “biblically aligned” companies, with ETFs like BIBL and PRAY leading the trend.

Related financial concepts

Price vs Value

In L’Argent, Zola portrays a world where financial speculation takes on a religious fervor, blurring the line between what something costs and what it is worth. This distinction echoes the financial concept of price versus value. The price reflects what the market is willing to pay at a moment in time, while value reflects the underlying fundamentals such as assets or cash flows. In the book, characters often worship price movements as if they were divine signs, forgetting that markets can be irrational and driven by emotion rather than reality. This parallels how modern investors sometimes chase rising prices without questioning intrinsic value, illustrating the timelessness of Zola’s critique.

Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) model

A DCF model seeks to calculate the true value of an asset by estimating its future cash flows and discounting them back to the present. This rational, analytical approach contrasts sharply with the speculative excesses described in L’Argent, where anticipated gains and promised fortunes overshadow the analysis using real economic output. In a sense, a DCF is the opposite of the “faith-based finance” depicted by Zola: instead of belief, charisma, or collective enthusiasm, it relies on measurable expectations and the time value of money. If Zola’s financiers had applied something like a modern DCF approach, their illusions of endless prosperity would likely have dissolved, revealing how fragile and unsupported their dreams truly were.

Zola’s narrative anticipates key ideas from behavioral economics, which studies how human biases systematically influence financial decisions. In L’Argent, investors fall prey to herd behavior, overconfidence, illusion of control, and the “narrative fallacy,” believing in grand stories of progress and fortune. These behaviors mirror well-documented cognitive biases that affect markets today, bubbles, panics, and irrational exuberance. Zola intuitively captures how money can become a quasi-religious force, shaping collective psychology and pushing individuals to act against their rational interests. Behavioral economics formalizes these observations, showing that markets are not purely logical systems but human and emotional ones, just as Zola described.

In L’Argent, Zola forges a powerful equivalence between religion and finance to show how belief, more than metal or marble, mints value. By sacralizing the Exchange, the bank, and the financier himself, he renders capitalism’s success contingent on liturgy: architecture that reassures, rituals that discipline, and a priesthood of leaders who promise salvation through profit. The crowd’s devotions inflate prices the leader’s “revelations” and, as in any cult of miracles, the crash arrives as a kind of failed prophecy, exposing how the same belief that creates wealth can just as quickly unmake it.

Why should you be interested in this post?

By linking Zola’s 19th-century novel to today’s financial concepts, from credit and bubbles to ethical and faith-based investing, it reveals how belief still drives markets as much as numbers do.

Related posts on the SimTrade blog

Financial concepts

▶ William LONGIN How to compute the present value of an asset?

Useful resources

Articles and books

Keynes J.M. (1936) The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, London: Macmillan (reprinted 2007).

Legoyt A. (1871-1872) La population française d’après le recensement de 1866, Journal de la Société Statistique de Paris , 12-13: 1-10.

Zola E. (1891) L’argent, Bibliothèque Charpentier, Paris.

SimTrade

SimTrade course Financial analysis

Others

About the author

The article was written in November 2025 by William LONGIN (Sorbonne School of Economics, Master in Money Banking Finance Insurance, 2024-2026)

▶ Read all articles by William LONGIN.