In this article, Snehasish CHINARA (ESSEC Business School, Grande Ecole Program – Master in Management, 2022-2025) explores the optimal capital structure for firms, which refers to the balance between debt and equity financing. This post dives into the article written by Modigliani and Miller (1963) which explores the case of corporate tax and a frictionless market (no bankruptcy costs).

Introduction to Modigliani and Miller Propositions

In 1958, Franco Modigliani and Merton Miller introduced a groundbreaking theory on capital structure, famously known as the M&M Proposition. Their research concluded that, under certain ideal conditions, the way a company finances itself—whether through debt or equity—does not affect its overall value. This result, known as the Capital Structure Irrelevance Principle, was based on assumptions such as no corporate taxes, no bankruptcy costs, and perfect capital markets. The intuition behind this idea is simple: if investors can create their own leverage by borrowing personally at the same rate as firms, then a company’s financing mix should not matter for its value.

According to M&M Proposition I (1958), in a frictionless world:

where:

- VL is the value of a levered firm using debt.

- VU is the value of a unlevered firm not using debt but only equity

Key Assumptions:

- No taxes (in reality, firms pay corporate taxes).

- No bankruptcy costs (in reality, firms pay costs if they go bankrupt).

- No financial distress (in reality, too much debt can make investors nervous).

However, this initial model had a major limitation: it ignored the effect of corporate taxes. In reality, most governments tax corporate profits, but they allow firms to deduct interest expenses on debt from taxable income. This means that using debt provides a tax advantage, which was missing from the 1958 model. Recognizing this, Modigliani and Miller revised their original work in 1963, introducing the impact of corporate taxes. Their new findings dramatically changed the conclusion: debt financing increases firm value because interest payments reduce taxable income, creating a tax shield. This update laid the foundation for modern corporate finance by showing that, with corporate taxes, firms should prefer debt over equity.

Modigliani-Miller 1963 Theorem (M&M 1963)

Modigliani and Miller’s 1963 revision to their capital structure theory introduced the concept of corporate taxes, which has a crucial impact on their earlier conclusions. They recognized that, in most economies, governments impose corporate income tax, but companies can deduct interest payments on debt from their taxable income. This interest tax-shield increases the after-tax profits of a firm and thereby raises its overall value.

The tax shield refers to the reduction in taxable income that results from interest payments on debt. Since interest expenses are tax-deductible, they effectively reduce the amount of taxes a company owes. This provides a direct financial benefit to firms that use debt financing, making it a valuable tool for optimizing capital structure.

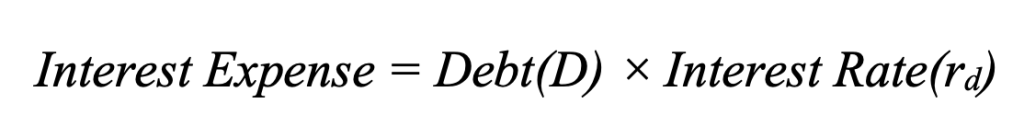

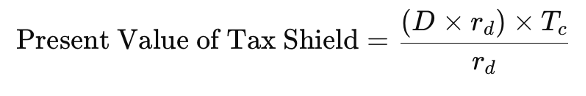

The formula for the tax shield is:

Since interest expense is calculated as:

Therefore, the tax shield for a single year becomes:

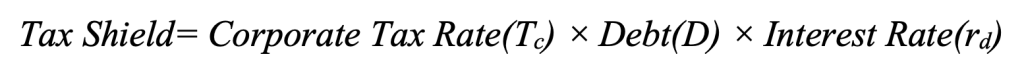

The Modigliani-Miller (1963) model assumes perpetual debt primarily for simplification and mathematical clarity. The use of perpetual debt helps in calculating the present value of the tax shield without the need for complex discounting over a finite period.

If the firm has perpetual debt, meaning it never repays the principal and continues paying interest forever, the total value of the tax shield is found by calculating the present value of all future tax shield benefits. Since the tax shield is received every year indefinitely, its present value is:

Using the cost of debt (rd) as the discount rate, we get:

The (rd) cancels out, simplifying to:

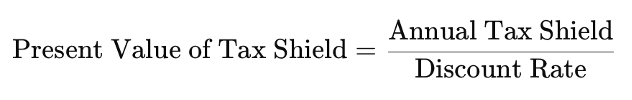

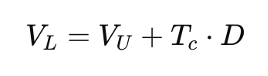

This means that, under the M&M (1963) proposition, the value of a leveraged firm is given by:

where:

- VL is the value of a levered firm using debt.

- VU is the value of a unlevered firm not using debt but only equity

- Tc is the Corporate tax rate

- D is the amount of debt of the firm

This formula shows that the value of a firm increases by the amount of tax shield (Tc⋅D) when debt is introduced into the capital structure. The more debt a company takes on, the greater the tax benefit, making debt financing more attractive than equity financing.

Figure 1. Firm Value vs Debt according to M&M 1963 Theorem

In simple terms, taxes make debt financing more beneficial because firms pay interest on debt before paying taxes, reducing their taxable income. On the other hand, dividends paid to equity shareholders are not tax-deductible, meaning that firms must pay taxes on their entire profit before distributing dividends.

Implication for Capital Structure Decisions:

Firms benefit from using debt due to the tax shield, leading to a preference for more leverage.

The Modigliani-Miller (1963) model with taxes suggests that because of the tax shield on debt, a firm’s value increases as it takes on more debt. The formula for value of a levered firm according to M&M(1963) shows that every additional unit of debt directly increases firm value by the tax savings it provides. In theory, this means that a firm should finance itself entirely with debt (100% debt financing) to maximize its value. This is a significant departure from M&M (1958), where capital structure had no effect on firm value.

Limitations

However, in real-world scenarios, firms do not rely solely on debt. This is because excessive debt increases the risk of financial distress and bankruptcy costs, which M&M (1963) did not initially consider.

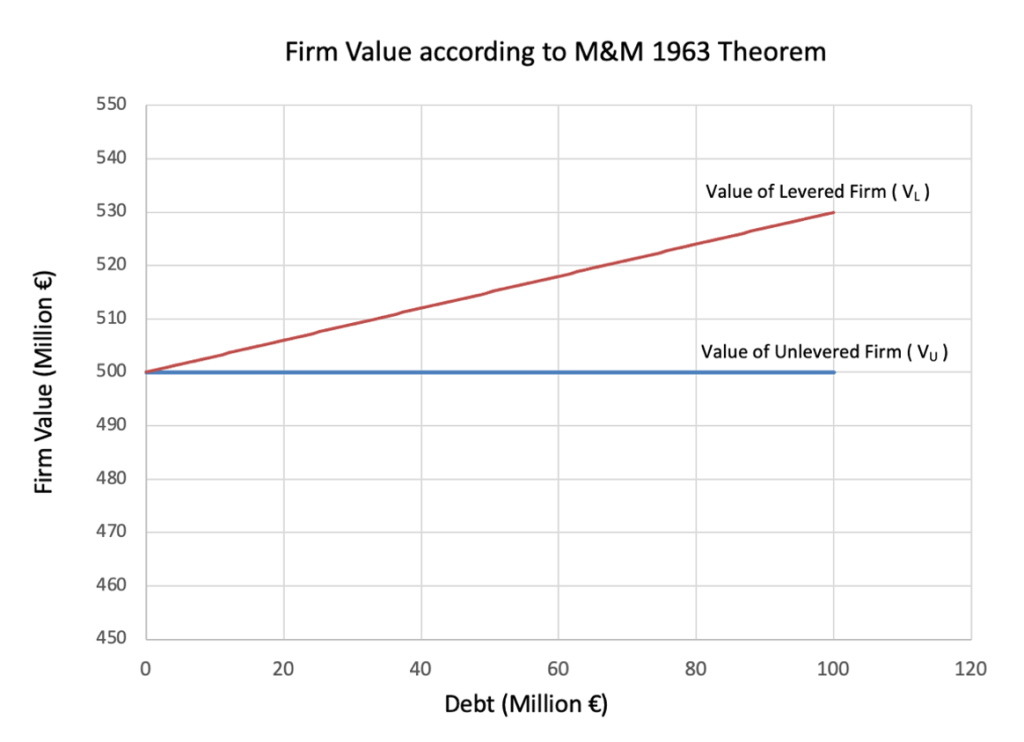

Case Study: Implications of M&M 1963 (Optimal Capital Structure with corporate taxes)

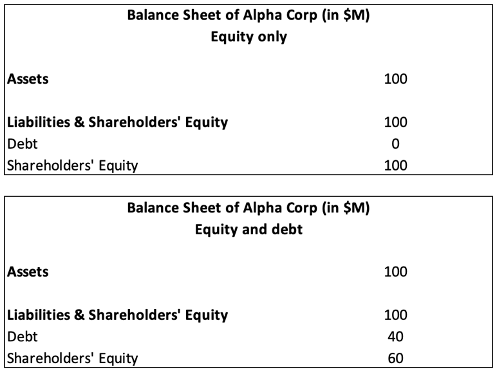

Alpha Corp operates in an imperfect capital market (with taxes only). It has two financing options for the capital structure:

- Option 1: equity only (100% equity, 0% debt)

- Option 2: debt and equity (60% equity, 40% debt)

Each option funds a $100 million investment that generates an annual operating income of $10 million. The risk-free interest rate is 5%, and the corporate tax rate is 30%.

Figure 2. Simplified Balance Sheet of Alpha Corp

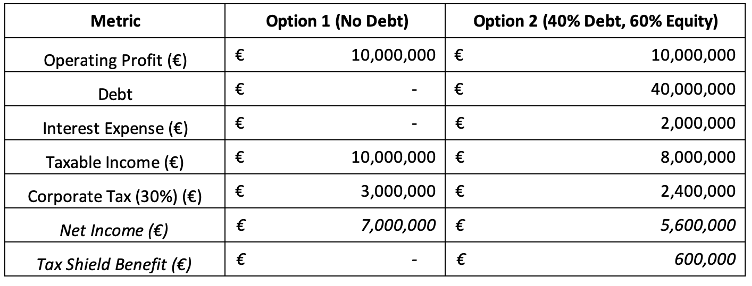

Table 1. M&M 1963: an Example

Based on Table 1, the key takeaways are as follows:

1.Debt Creates a Tax Shield:

- Under Option 2 (40% debt, 60% equity), Alpha Corp pays €2 million in interest expense, reducing taxable income from €10 million to €8 million.

- This results in a lower corporate tax payment (€2.4 million instead of €3 million), leading to a €600,000 tax shield benefit.

2.Net Income is Lower with Debt, But Firm Value Increases:

- Despite reducing tax liability, net income under Option 2 (€5.6 million) is lower than Option 1 (€7 million) because of interest expenses.

- However, the firm’s total value increases due to the tax shield, meaning equity holders still benefit from debt financing.

How Modigliani-Miller (1963) Redefined the Cost of Equity and WACC from Modigliani-Miller (1958)

In Modigliani-Miller (1958), the firm’s capital structure—the mix of debt and equity—was considered irrelevant to its overall cost of capital (WACC) and, by extension, its firm value. This proposition, based on ideal market conditions (no taxes, no bankruptcy costs), argued that whether a firm is financed by debt or equity, the overall cost of capital remains unchanged. The cost of equity increases with leverage because equity holders demand higher returns to compensate for the additional financial risk, but this increase in cost of equity was offset by the lower cost of debt. Therefore, WACC stayed constant regardless of a firm’s capital structure.

However, when Modigliani and Miller (1963) introduced corporate taxes into their model, they demonstrated a significant change in the cost of capital (WACC) and cost of equity dynamics. With the tax deductibility of interest payments on debt, the cost of debt is effectively reduced, which leads to a reduction in WACC. This creates a clear benefit for firms that use more debt in their capital structure, making debt financing a value-enhancing tool. Let’s explore these key differences in detail.

Impact on the Cost of Equity (rE)

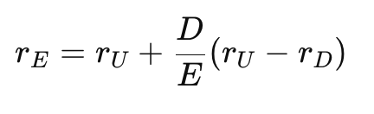

MM (1958) – Cost of Equity Increases with Leverage

Under the Modigliani-Miller (1958) framework, the cost of equity (rE) increases as a firm takes on more debt because equity holders demand higher returns for taking on additional risk due to leverage. The relationship between cost of equity and leverage is described by the following formula:

where:

- rE is the cost of equity for a levered firm

- rU is the cost of equity for an unlevered firm

- rD is the cost of debt

- D/E is the debt to equity ratio measuring leverage

This formula shows that as a firm increases its debt, its cost of equity increases to compensate for the increased financial risk borne by equity holders. However, since debt is cheaper than equity, the overall WACC remains unchanged.

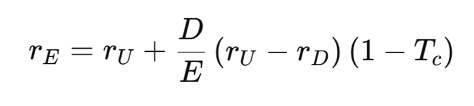

MM (1963) – Tax Shield Reduces the Impact on Cost of Equity In MM (1963), the introduction of corporate taxes changes the scenario. Since interest expenses on debt are tax-deductible, the effective cost of debt (rD) becomes lower. This reduces the overall risk for the firm and, therefore, the increase in the cost of equity (rE) is less severe than in MM (1958). The new formula for cost of equity becomes:

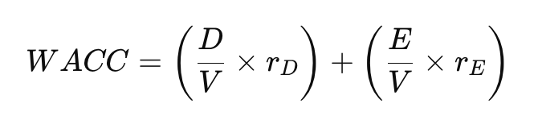

Impact on the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC)

M&M (1958) – WACC Remains Constant Regardless of Leverage

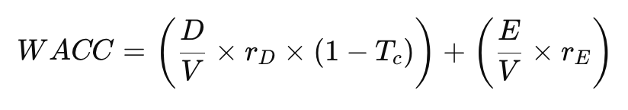

In MM (1958), because the increase in the cost of equity (rE) offsets the benefit of cheaper cost of debt (rD), the WACC remains constant no matter the debt-to-equity ratio. The formula for WACC in this model is:

where:

- V=D+E is the total firm value

- rE is the cost of equity for a levered firm

- rD is the cost of debt

- D is the total debt

- E is the total equity

According to MM (1958), since debt and equity are in perfect balance (i.e., the increase in the cost of equity (rE) is offset by the lower cost of debt (rD)), the WACC stays constant. The capital structure—how much debt or equity a firm uses—has no effect on the overall cost of capital or the firm’s value in a world without taxes.

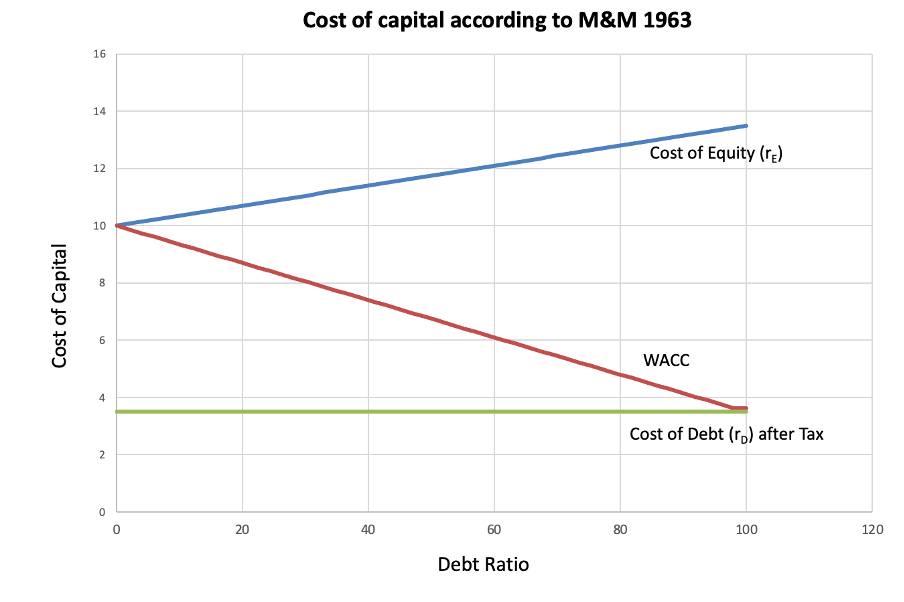

MM (1963) – WACC Declines as Debt Increases

With the introduction of taxes, MM (1963) shows that WACC decreases as a firm increases its debt. The tax shield created by the deductibility of interest payments lowers the effective cost of debt (rD), making debt financing more attractive.

The formula for after-tax WACC in MM (1963) is:

Figure 3. Modigliani-Miller View Of Gearing And WACC: With Taxation (MM 1963)

Case Study: Implications of M&M 1963 (Optimal Capital Structure with corporate taxes)

Alpha Corp operates in a capital market (no bankruptcy costs, and no market imperfections). It has two financing options:

- Option 1: Fully equity-financed (No debt with Corporate Taxes of 30%)

- Option 2: 40% Debt, 60% Equity (without Corporate Taxes)

- Option 3: 40% Debt, 60% Equity (with Corporate Taxes of 30% )

Each option funds a $100 million investment that generates an annual operating income of $10 million. The risk-free interest rate is 5%, and the required return on equity is 10%.

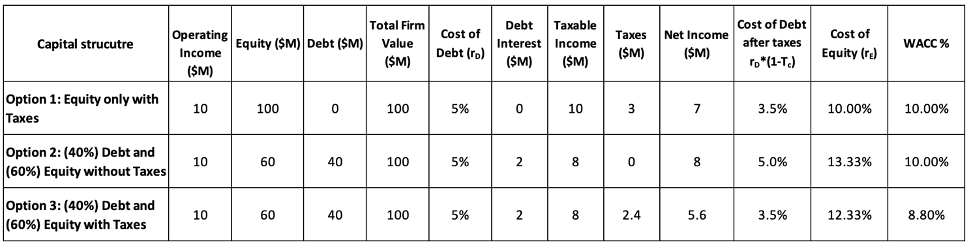

Figure 4. Modigliani-Miller View Of Gearing And WACC: With Taxation (MM 1963)

Table 2. M&M 1963: an Example

Key takeaways from this example are as follows :

1. Corporate Taxes Make Debt Financing More Attractive by Reducing the Effective Cost of Debt

- In a no-tax world (M&M 1958, Option 2), firms are indifferent between debt and equity, as capital structure does not affect WACC.

- However, M&M (1963) proves that in a taxed environment (Option 3), debt financing creates value because interest payments reduce taxable income, leading to lower corporate taxes.

- This is called the “tax shield” effect, where firms pay less in taxes by using debt, increasing after-tax cash flows available to shareholders.

2. WACC Declines with Leverage When Corporate Taxes Exist, Unlike in M&M (1958)

- In M&M (1958) (no taxes, Option 2), WACC remains constant at 10%, regardless of leverage.

- M&M (1963) (Option 3) introduces taxes, causing WACC to drop to 8.80% due to the tax shield.

- Strategic Takeaway: Firms can reduce their cost of capital and increase firm value by incorporating moderate levels of debt into their capital structure.

3. Cost of Equity Increases with Debt, But the Tax Shield Reduces the Rate of Increase

- Higher leverage increases financial risk for shareholders, leading to a higher required return on equity (rE).

- In Option 2 (M&M 1958, No Taxes), introducing 40% debt raises the cost of equity to 13.33% due to added risk.

- In Option 3 (M&M 1963, With Taxes), the cost of equity only increases to 12.33%, because the tax shield offsets part of the financial risk.

- The cost of debt before taxes is 5%.

- Due to the corporate tax rate (30%), the effective cost of debt is reduced: rDafter-tax= rD ×(1−Tc)

- Comparing Financing Costs in Option 3:

- Cost of Equity (rE) = 12.33%

- After-Tax Cost of Debt (rD) = 3.5%

- Debt financing is significantly cheaper than equity financing after adjusting for the tax shield.

- Firms should utilize debt strategically to lower overall financing costs.

- M&M (1963) suggests using more debt to reduce WACC, but in reality, excessive debt increases financial distress risks.

- While debt reduces WACC through the tax shield, too much debt leads to higher bankruptcy risks, credit downgrades, and operational constraints.

- Most firms balance debt and equity to optimize WACC, using debt to take advantage of tax savings without excessive financial risk.

Takeaways on Optimal Debt Structure and Bankruptcy Costs from M&M 1963 Theorem

The Modigliani-Miller (1963) proposition demonstrated that the presence of corporate taxes fundamentally changes the implications of capital structure on firm value. Unlike their earlier 1958 proposition, where capital structure was deemed irrelevant, the 1963 revision highlighted the benefits of debt financing due to the tax shield effect. Since interest expenses on debt are tax-deductible, firms can reduce their taxable income and, consequently, their tax obligations. This finding suggests that, in a world with corporate taxes and no other frictions, firms should finance themselves entirely with debt to maximize their value.

The M&M (1963) proposition remains a cornerstone in understanding capital structure decisions, demonstrating that debt financing enhances firm value through tax savings. However, in practice, firms must carefully balance leverage to avoid excessive financial distress. The optimal capital structure is not purely debt-driven but rather a carefully calibrated mix of debt and equity that maximizes firm value while maintaining financial stability.

Why Should I Be Interested in This Post?

This post explains a key concept in corporate finance—how debt financing affects firm value through corporate tax benefits and financial risks. If you’re a student, finance professional, or investor, understanding the Modigliani-Miller (1963) proposition will help you grasp why companies use debt. With clear explanations, real-world examples, and Excel-based analysis, this post provides practical insights into optimal capital structure decisions.

Related posts on the SimTrade blog

▶ Snehasish CHINARA Optimal capital structure with no taxes: Modigliani and Miller 1958

▶ Snehasish CHINARA Solvency and Insolvency in the Corporate World

▶ Snehasish CHINARA Illiquidity, Liquidity and Illiquidity in the Corporate World

▶ Snehasish CHINARA Illiquidity, Solvency & Insolvency : A Link to Bankruptcy Procedures

▶ Snehasish CHINARA Chapter 7 vs Chapter 11 Bankruptcies: Insights on the Distinction between Liquidations & Reorganisations

▶ Snehasish CHINARA Chapter 7 Bankruptcies: A Strategic Insight on Liquidations

▶ Snehasish CHINARA Chapter 11 Bankruptcies: A Strategic Insight on Reorganisations

▶ Akshit GUPTA The bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers (2008)

▶ Akshit GUPTA The bankruptcy of the Barings Bank (1996)

▶ Anant JAIN Understanding Debt Ratio & Its Impact On Company Valuation

Useful resources

Academic research

Modigliani, F., M.H. Miller (1958) The Cost of Capital, Corporation Finance and the Theory of Investment, American Economic Review, 48(3), 261-297.

Modigliani, F., M.H. Miller (1963) Corporate Income Taxes and the Cost of Capital: A Correction, American Economic Review, 53(3), 433-443.