In this article, Snehasish CHINARA (ESSEC Business School, Grande Ecole Program – Master in Management, 2022-2025) delves into liquidity and illiquidity, key concepts in the corporate world.

Liquidity and Illiquidity Definitions

Liquidity is an important economic concept that can be applied to individuals, companies and financial institutions. In this article, we deal with liquidity at the firm level, which involves the liquidity of the assets and the due date of the liabilities.

In a corporate context, liquidity refers to the ability and capacity of accompany to meet its short-term financial obligations using its available cash or easily convertible assets. Short-term financial obligations refer to the payment of the salary to employees, the invoices to providers, the interests of loans and bonds to the creditors, the taxes to the state, etc. Current assets refer to cash, marketable securities, accounts receivable, and inventories. They are categorized as liquid assets due to their relative accessibility and low conversion time.

To assess liquidity, we need to compare the liquidity of assets and the due date of liabilities. In practice, assets and liabilities can be found with their amount in the balance sheet of the firm. For an asset, liquidity is the ability to quickly convert the asset into cash at its fair market value (with relatively small market impact). For a liability, the due date is key.

Illiquidity refers to the inability of a company to convert assets into cash quickly enough to meet short-term financial obligations as they come due. This condition arises from a mismatch in the timing of cash inflows and outflows (illiquidity or a fundamental deficiency in overall financial health (insolvency). For instance, a firm might hold substantial non-liquid assets (e.g., accounts receivable or inventory) that are valuable but not immediately accessible for use in settling debts. The states of liquidity and illiquidity are generally viewed as a short-term liquidity risk and is often addressed through measures such as enhanced cash flow management, securing bridge financing, or leveraging credit facilities.

Causes of Illiquidity

The following are few causes of illiquidity:- Poor Cash Management – Inefficient management of cash flows, such as misaligning income and expenses, is a primary cause of illiquidity. Businesses that fail to maintain adequate liquidity reserves or do not accurately forecast future cash needs may face severe short-term financial strain. For instance, a company might overestimate receivables collections or underestimate operational expenses, leading to insufficient funds for immediate obligations.

- External Shocks:

- Market Downturns: Economic recessions, sudden market volatility, or a decline in demand for products/services can significantly reduce cash inflows, creating liquidity stress.

- Seasonal Variations: Businesses with highly seasonal revenue streams, such as retail or tourism, may experience cash shortages during off-peak periods when income generation is low but fixed costs remain constant.

- Supply Chain Disruptions- Unexpected events like raw material shortages, logistical delays, or geopolitical risks can disrupt production cycles, leading to revenue delays and payment bottlenecks.

- Over-Leverage – Excessive reliance on debt without adequate planning for repayments can strain liquidity. Companies that overextend themselves with short-term borrowing may face difficulties rolling over or refinancing debt, especially in tight credit markets.

- Rapid Expansion- Aggressive growth strategies, such as entering new markets or launching new products, can deplete cash reserves if expenses outpace revenue generation. For example, increased capital expenditures or marketing costs may lead to liquidity shortages during the early stages of expansion.

- Asset Illiquidity- Holding a significant portion of assets in non-liquid forms (e.g., real estate, long-term investments) reduces the ability to generate quick cash. While these assets contribute to the overall balance sheet value, their inability to be converted into liquid funds on short notice can exacerbate illiquidity during crises.

- Contractual Obligations- Fixed payment schedules for rent, salaries, or interest on loans can pressure liquidity when cash inflows do not align with payment deadlines. Even profitable businesses can face illiquidity if contractual commitments are poorly synchronized with revenue cycles.

- Credit Constraints – Difficulty accessing credit markets due to poor credit ratings, higher interest rates, or restrictive borrowing conditions can leave firms unable to secure short-term financing. Companies with a history of missed payments may struggle to find lenders willing to provide liquidity support.

Measuring Liquidity

Key Liquidity Metrics

Liquidity metrics provide a structured way to assess the ability of individuals, companies, or financial systems to meet short-term obligations. These metrics are foundational for understanding a financial entity’s operational efficiency and financial health.

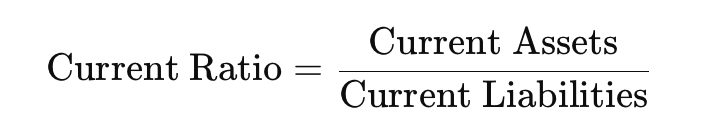

Current Ratio

- Purpose: Measures a company’s ability to cover its short-term obligations with its short-term assets.

- Interpretation: A ratio above 1 indicates that a company has more current assets than current liabilities, signalling good liquidity. However, an excessively high ratio might indicate inefficiency in utilizing resources.

Example – Consider two (non- financial) companies A & B

Company A:

- Current Assets = €200,000

- Inventory = €50,000

- Current Liabilities = €100,000

Quick Ratio (Company A) = (200,000 – 50,000)/100,000 = 1.5

Company B:

- Current Assets = €80,000

- Inventory = €30,000

- Current Liabilities = €100,000

Quick Ratio (Company B) = (80,000-30,000)/100,000 = 0.5

Here, Company A maintains sufficient liquidity even after excluding inventory, while Company B faces liquidity concerns.

Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC)

- Purpose: Evaluates the efficiency of a company in managing its working capital by measuring the time it takes to convert investments in inventory and receivables into cash.

- Interpretation: A shorter cycle indicates faster liquidity, suggesting effective operational management.

Example – Consider two (non- financial) companies A & B

Company A:

- DIO = 40 days

- DSO = 30 days

- DPO = 45 days

CCC(A)=40+30−45=25 Days

Company B:

- DIO = 80 days

- DSO = 50 days

- DPO = 40 days

CCC (B)=80+50−40=90 Days

Company A has a shorter CCC, indicating quicker cash turnover, while Company B takes longer to convert inventory and receivables into cash, leading to potential liquidity constraints.

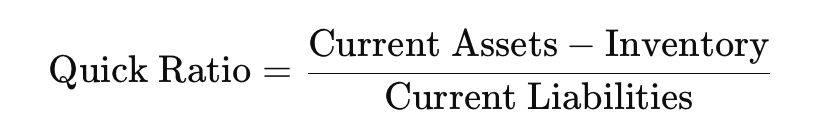

Quick Ratio (Acid-Test Ratio)

- Purpose: Excludes inventory from current assets to provide a stricter measure of liquidity, as inventory may not be easily converted to cash.

- Interpretation: A ratio above 1 typically reflects strong liquidity, especially for companies in industries where inventory turnover is slow.

Example – Consider two (non- financial) companies A & B

Company A:

- Current Assets = €200,000

- Inventory = €50,000

- Current Liabilities = €100,000

Quick Ratio (Company A) = (200,000 – 50,000)/100,000 = 1.5

Company B:

- Current Assets = €80,000

- Inventory = €30,000

- Current Liabilities = €100,000

Quick Ratio (Company B) = (80,000-30,000)/100,000 = 0.5

Here, Company A maintains sufficient liquidity even after excluding inventory, while Company B faces liquidity concerns.

Funding Liquidity

Funding liquidity is the ability of firms, financial institutions, or individuals to meet short-term obligations as they come due, using available cash, liquid assets, or borrowing capacity. It reflects the financial health and cash management practices of an entity.

Key Characteristics:

- Access to Cash: Availability of cash or near-cash assets.

- Borrowing Capacity: Ability to raise funds through credit lines or issuing debt.

- Short-Term Solvency: Ensuring that obligations such as payroll, supplier payments, and loan repayments are met on time.

Examples:

- A company maintaining a cash reserve or a revolving credit line for emergencies.

- Banks relying on interbank lending markets for overnight funding.

Consequences of Illiquidity

Illiquidity can have a cascading impact on a business’s financial health and operational stability. The impact ranges from borrowing difficulties to bankruptcy. Below are the key consequences of illiquidity:

- Missed Payments to Creditors – Companies facing illiquidity may struggle to meet immediate financial obligations such as loan repayments, supplier invoices, or tax liabilities. This can damage relationships with creditors and suppliers, leading to stricter payment terms, higher interest rates, or the refusal of future credit. Missed payments may also result in legal penalties or lawsuits, further exacerbating financial difficulties.

- Short-Term Borrowing – To address cash flow gaps, businesses often resort to short-term borrowing, such as credit lines or bridge loans. While this provides immediate relief, repeated reliance on short-term financing can increase interest expenses and leverage, making the company more vulnerable to future liquidity crises. High debt levels may also negatively impact credit ratings, limiting access to affordable financing.

- Asset Liquidation – Companies may be forced to sell non-core or underperforming assets to generate quick cash. While this can temporarily alleviate liquidity pressure, it can weaken the firm’s long-term strategic position if valuable or income-generating assets are sold. Additionally, asset liquidation in distress scenarios often leads to unfavourable valuations, further diminishing the firm’s financial standing.

- Operational Disruptions – A lack of liquidity can hinder day-to-day operations, such as the inability to purchase raw materials, pay employees, or fund marketing initiatives. These disruptions can result in reduced productivity, loss of market share, and damage to the company’s reputation among customers and stakeholders.

- Increased Cost of Capital – Persistent illiquidity may lead to higher borrowing costs as creditors perceive the company as a higher-risk borrower. This increased cost of capital can strain cash flows further and limit the company’s ability to invest in growth opportunities.

- Employee Layoffs or Salary Delays – In severe cases, companies may delay salaries or initiate workforce reductions to conserve cash. This can lead to lower employee morale, higher attrition rates, and loss of critical talent, affecting the firm’s long-term capabilities and performance.

- Decline in Market Confidence – Illiquidity signals financial distress to investors, customers, and suppliers. A decline in market confidence can lead to reduced stock prices, difficulty in securing contracts, and a potential withdrawal of customer deposits (in the case of financial institutions).

- Escalation to Insolvency – If illiquidity persists and the company cannot stabilize cash flows, it may transition into insolvency, where liabilities exceed assets. This often leads to bankruptcy proceedings, such as liquidation (Chapter 7) or reorganisation (Chapter 11).

- Regulatory and Legal Penalties – Failure to meet statutory obligations, such as tax payments or compliance filings, can result in regulatory fines or legal action. For financial institutions, illiquidity may lead to intervention by regulators or central banks.

- Bankruptcy – If the liquidity crisis persists, the company may be forced to restructure its debts, sell assets at distressed prices, or seek emergency funding. In extreme cases, prolonged illiquidity can result in insolvency, pushing the firm toward bankruptcy proceedings, such as Chapter 7 liquidation (where assets are sold to repay creditors) or Chapter 11 reorganization(where the company restructures to regain financial stability).

Liquidity Management for Companies

Liquidity management is a cornerstone of a company’s financial health, ensuring that it can meet its short-term obligations and operate smoothly without disruptions. Effective liquidity management safeguards against financial distress, supports growth, and enhances the company’s ability to respond to market opportunities or challenges.

Tools for Liquidity Management

1.Cash Flow Forecasting:

- Purpose: Predicts cash inflows and outflows over a specific period, allowing companies to anticipate liquidity needs.

- Implementation: Regularly updating forecasts based on operational activities, seasonal trends, and external market factors.

- Benefits: Helps identify potential shortfalls or surpluses and plan financing or investment activities accordingly.

2.Credit Lines:

- Purpose: Pre-approved borrowing arrangements with banks provide immediate access to funds when needed.

- Implementation: Companies negotiate revolving credit facilities with financial institutions.

- Benefits: Offers flexibility to address liquidity shortfalls without lengthy approval processes.

3.Liquidity Buffers:

- Purpose: Reserve cash or easily liquidated assets set aside to manage unforeseen circumstances.

- Implementation: Maintaining a percentage of revenue or working capital in liquid form.

- Benefits: Acts as an emergency fund to meet unexpected expenses or capitalize on opportunities.

4.Working Capital Optimization:

- Purpose: Efficiently managing current assets and liabilities to improve liquidity.

- Implementation:

- Reducing inventory levels without compromising production.

- Negotiating longer payment terms with suppliers.

- Accelerating accounts receivable collection.

- Benefits: Frees up cash for other uses without requiring additional financing.

5.Treasury Management Systems (TMS):

- Purpose: Automates liquidity tracking and management processes.

- Implementation: Deploying software to consolidate cash positions, manage risks, and optimize cash usage.

- Benefits: Enhances real-time visibility into cash flows and simplifies decision-making.

Building Strong Liquidity Buffers

A well-structured liquidity buffer is essential for corporate firms to withstand financial shocks, economic downturns, and unexpected cash flow disruptions. Establishing and maintaining sufficient liquidity ensures that companies can meet their short-term obligations, maintain investor confidence, and continue operations smoothly during periods of uncertainty. Below are key strategies that firms can adopt to strengthen their liquidity buffers.

Liquidity Reserves:

Liquidity reserves refer to the cash and readily accessible liquid assets that a company maintains to address unforeseen financial needs. These reserves act as a financial safety net, ensuring that a firm can continue operations even during economic downturns, market disruptions, or revenue shortfalls.

Maintain cash reserves or liquid assets to manage unexpected shortfalls. A robust liquidity buffer acts as a financial safety net during crises.

Key Actions:

- Allocate a percentage of revenue to a contingency fund.

- Invest in low-risk, short-term instruments like treasury bills.

- Regularly Review Liquidity Needs

- Diversify Cash Holdings Across Financial Institutions

Credit Line Management:

Beyond maintaining cash reserves, companies should have access to credit facilities that provide immediate funding when needed. A well-managed credit line acts as an additional liquidity buffer and prevents financial distress when operational cash flows are temporarily constrained.

Example: A revolving credit line ensures access to immediate funding without lengthy approval processes.

Working Capital Optimization:

Working capital represents a company’s ability to manage its short-term assets and liabilities efficiently. Optimizing accounts receivable, accounts payable, and inventory can significantly enhance liquidity without the need for external borrowing or additional capital injections.

Example: Implementing stricter credit terms for customers and negotiating extended payment terms with suppliers.

Why Should I Be Interested in This Post?

Understanding liquidity and its management is crucial not just for financial professionals but for anyone navigating the modern economic landscape. Whether you are an investor assessing asset portfolios, a corporate leader ensuring operational stability, or a student preparing for a career in finance, liquidity forms the foundation of informed decision-making. This post provides a comprehensive guide to the causes, consequences, and tools of liquidity management, equipping you with the knowledge to evaluate financial health, mitigate risks, and capitalize on opportunities. In a world where liquidity—or the lack thereof—can mean the difference between success and failure, mastering this concept empowers you to make smarter financial decisions, stay resilient during crises, and thrive in dynamic markets.

Related posts on the SimTrade blog

▶ Snehasish CHINARA Illiquidity, Solvency & Insolvency : A Link to Bankruptcy Procedures

▶ Snehasish CHINARA Chapter 7 vs Chapter 11 Bankruptcies: Insights on the Distinction between Liquidations & Reorganisations

▶ Snehasish CHINARA Chapter 7 Bankruptcies: A Strategic Insight on Liquidations

▶ Snehasish CHINARA Chapter 11 Bankruptcies: A Strategic Insight on Reorganisations

▶ Akshit GUPTA The bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers (2008)

▶ Akshit GUPTA The bankruptcy of the Barings Bank (1996)

▶ Anant JAIN Understanding Debt Ratio & Its Impact On Company Valuation