In this article, Alberto BORGIA (ESSEC Business School, Global Bachelor in Business Administration (GBBA), Exchange student, Fall 2025) explains about EBITDA, how it can be used, its advantages and disadvantages.

Introduction

Earning Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortization (EBITDA) is ones of the most used financial metric and its goal is to understand a company’s operating performance before considering the effects of financial choices (interests), taxation and non-cash accounting charges related to long-lived asset and acquired intangibles.

So in intuition behind it is that if two or more firms sell similar products, the analyst should be able to compare their “core operating engine”, even if they differ from a debt (higher debt), tax (different tax jurisdiction) or asset base prospective.

Because EBITDA is a key component capable of influence valuation and decisions, it is crucial to understand both how it is obtained and what it does.

How it is obtained

To calculate this metric, we begin with the income statement and add back the expenses that are excluded by the EBITDA definition:

EBITDA = Net Income + Interest + Taxes + Depreciation + Amortization

Another way is to start from the EBIT:

EBITDA = EBIT + Depreciation + Amortization

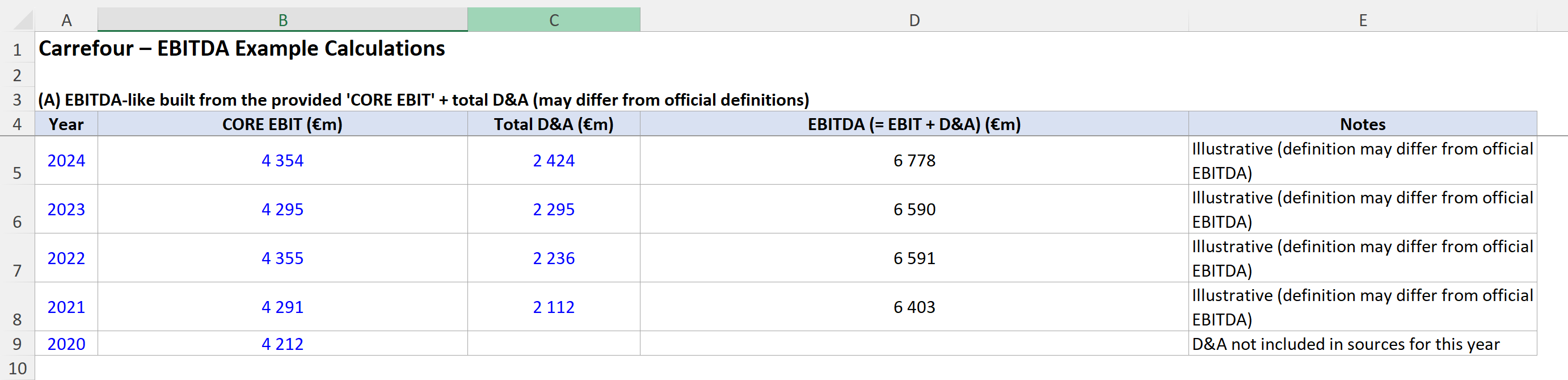

Using Carrefour as a real-case example, I calculated EBITDA starting from the company’s income-statement figures. First, I reproduced an “operating-style” EBITDA by taking Gross Margin and subtracting selling, general and administrative expenses, which gives a core operating profit measure before financing and taxes. Then, for a second approach, I computed EBITDA as Recurring Operating Income + Depreciation + Amortization. This shows how EBITDA is obtained in practice from published financial statement components.

These two formulae can look clean and easy, but the real computation is messier, depending on how the company structure his income statement and on what is included in the amortization and depreciation class. For these reasons EBITDA is usually accompanied by a set of clear definitions and reconciliations.

Another key factor is that the “earnings” are not always interpreted in the same way, that is why the SEC has decided that in the context of EBITDA and EBIT described in its adopting release, “earnings” means GAAP net income as presented in the statement of operations. So, if a measure is calculated differently, it should not be labeled EBITDA, but Adjusted EBITDA.

Adjusted EBITDA

For many documents we see the term Adjusted EBITDA, because it modifies the measure by excluding values that are considered by the management as “non-core” or “non-recurring”. These adjustments typically include items such as restructuring costs, acquisition-related expenses, unusual or non-recurring gains and losses, and stock-based compensation. The goal is to estimate a normalized operating result. This can however create risks when comparing different firms or the same one in different years.

What it is used for

The reasons why EBITDA is one of the metrics most taken into account by financial analysts are multiple as its ways of use. First of all, by excluding interest rates, it is suitable as a proxy for comparing companies from an operating perspective, even when they have different tax or capital structures. It is then used to compare various risk indicators or to limit leverage and protect lenders (in the debt market).

It is also used for company valuation and for the calculation of multiples, such as EV/EBITDA. Here, EV indicates the total value of the firm. According to the technical literature, the reasons why this multiple is particularly useful and widely used include, for example, the possibility of calculating it even when net income is negative, for this reason, it is extremely common in markets where significant infrastructure investments are present and in leveraged buyouts and naturally because it allows the comparison of companies with totally different levels of financial leverage.

They are also particularly useful (EBITDA and its variants) for communicating to investors and analysts, even though it is necessary to be especially careful about any modifications aimed at “inflating” the results.

Last it is considered by analysts as a starting point, pairing it with cash-flow measures, such as free cash flow, for a fuller view.

Advantages

There are several advantages to using EBITDA; for instance, it can be calculated quickly from publicly available financial statements or is often directly disclosed by companies. In industries where leverage varies a lot it is useful to analyze companies in it or when assessing a target in M&A where capital structure can change immediately after the acquisition. Finally operating results are less sensitive to life assigned to asset when we add back depreciation and amortization.

Disadvantages

However, EBITDA is also associated with several notable drawbacks. Even by adding back depreciation and amortization, the value does not take into account changes in working capital and capex needed to increase or maintain productive capacity, it is more like a “rough” measure of operating cash flows.

As previously noted, EBITDA is also susceptible to manipulation, as it is inherently open to interpretation. Consequently, it should be complemented with other financial metrics to provide a more comprehensive and balanced assessment, thereby reducing the risk of misinterpretation driven by management’s attempts to influence investors’ perceptions..

EBITDA Margin

To express the EBITDA relative to revenue, we can use EBITDA margin:

EBITDA Margin = EBITDA / Revenue

It is calculated to understand how much operating earnings the firm generates per unit of sales, in particular it can be used to compare a firm’s profitability with its peers or to track trends. Even though it is particularly useful in financial analysis, the EBITDA margin presents the same issues as the original metric. If the first value is defined incorrectly, then this one will also be wrong. Just like normal EBITDA, this metric can be used best when it is accompanied by Operating Cash Flow (OCF), which reflects the cash generated by a company’s core operating activities, and Free Cash Flow (FCF), which represents the cash available after capital expenditures necessary to maintain or expand the asset base, and by an industry context.

Example

I provide below an example for the computation of EBITDA based on Carrefour, a French firm operating in the retail sector, more precisely in mass-market distribution (retail grocery).

Example of EBITDA calculation: Carrefour

You can download the Excel file provided below, which contains the calculations of EBITDA for Carrefour.

Why should I be interested in this post?

EBITDA represents a fundamental concept for anyone who wants to build their career in the financial field, but not only. Understanding how it works, as well as its weaknesses and strengths, is necessary in order to build the knowledge required to become a competent and respected professional. This article, in fact, starts from the basics in order to explain the principles behind this metric even to those who are not in the field, helping them understand it.

Related posts on the SimTrade blog

▶ Cornelius HEINTZE DCF vs. Multiples: Why Different Valuation Methods Lead to Different Results

▶ Dawn DENG Assessing a Company’s Creditworthiness: Understanding the 5C Framework and Its Practical Applications

Useful resources

Deloitte Accounting Research Tool (DART) 3.5 EBIT, EBITDA, and adjusted EBITDA

Damodaran

Moody’s (202/11/2024) EBITDA: Used and Abused

Faria-e-Castro, M., Gopalan R., Pal, A, Sanchez J.M., and Yerramilli V. (2021) EBITDA Add-backs in Debt Contracting: A Step Too Far? Working paper.

Damodaran EBITDA vs cash flow logic; reinvestment/capex relevance

About the author

The article was written in December 2025 by Alberto BORGIA (ESSEC Business School, Global Bachelor in Business Administration (GBBA), Exchange student, Fall 2025).

▶ Read all articles by Alberto BORGIA.