In this article, Snehasish CHINARA (ESSEC Business School, Grande Ecole Program – Master in Management, 2022-2025) explores the optimal capital structure for firms, which refers to the balance between debt and equity financing. This post focuses on how the impact of personal taxes on the firm capital structure. The author unpacks Miller’s 1977 proposition, which presents a formula for calculating the right tax advantage of debt, and explains how it helps reconcile theory with what we actually observe in practice.

Introduction

When Modigliani and Miller introduced their capital structure theory in 1958, they shook the foundations of corporate finance. They argued that, in a perfect market with no taxes, no bankruptcy costs, and no frictions, a firm’s value is completely independent of how it is financed. In other words, it doesn’t matter whether a firm uses debt, equity, or a combination of both—the total firm value remains the same.

In 1963, Modigliani and Miller revised their theory to incorporate corporate taxes. With this adjustment, interest payments on debt are tax-deductible, and then provide firms with a “tax shield” that effectively reduces the cost of debt. This made debt financing more attractive than equity, leading to the conclusion that firms should increase their leverage to maximize their value (ideally reaching a 100 debt ratio). In the extreme, this version of the theory suggested that firms should be financed entirely with debt to benefit from the maximum tax advantage.

However, the real world tells a different story. Very few firms rely solely on debt. In fact, most maintain a balanced mix of debt and equity. If debt is supposedly so advantageous under corporate tax rules, why don’t we see more of it being used? This is where Merton Miller’s 1977 work offers a crucial refinement to the theory.

Miller introduced a critical yet often overlooked component into the capital structure discussion: personal taxes. While interest payments are tax-deductible at the corporate level, the income received by investors—whether as interest or dividends—is also subject to personal taxation. Importantly, interest income is often taxed at a higher rate than equity income (like capital gains or dividends). This means the supposed advantage of debt at the corporate level may be offset—or even completely nullified—by the higher tax burden borne by investors.

Modigliani-Miller 1963 Theorem (M&M 1963)

Let us first remind you about the main findings of Modigliani and Miller (1963). In their revision of their first article published a few years earlier (1958), their theory about the firm capital structure introduced corporate taxes, which has a crucial impact on their earlier conclusions which found that the capital structure was irrelevant. They recognized that, in most economies, governments impose corporate income tax, but companies can deduct interest payments on debt from their taxable income. This interest tax-shield increases the after-tax profits of a firm and thereby raises its overall value.

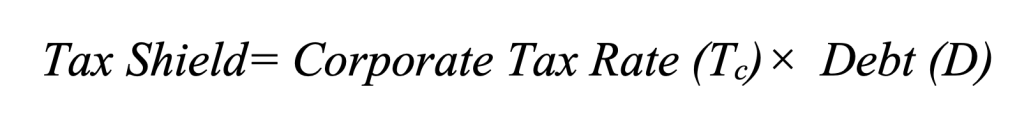

The tax shield refers to the reduction in taxable income that results from interest payments on debt. Since interest expenses are tax-deductible, they effectively reduce the amount of taxes a company owes. This provides a direct financial benefit to firms that use debt financing, making it a valuable tool for optimizing capital structure.

The formula for the tax shield is:

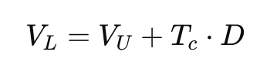

This means that, under the M&M (1963) proposition, the value of a leveraged firm is given by:

where:

- VL is the value of a levered firm using debt.

- VU is the value of a unlevered firm not using debt but only equity

- Tc is the Corporate tax rate

- D is the amount of debt of the firm

This formula shows that the value of a firm increases by the amount of tax shield (Tc⋅D) when debt is introduced into the capital structure. The more debt a company takes on, the greater the tax benefit, making debt financing more attractive than equity financing.

Miller (1977): The Role of Personal Taxes in Capital Structure

Modigliani and Miller’s 1963 revision made a powerful case for debt: because interest payments are tax-deductible, firms enjoy a tax shield that reduces their cost of capital. The logical (but extreme) implication of this idea was that firms should maximize debt in their capital structure. However, the theory still fell short of explaining reality—most firms do not load up on debt. Why?

This is where Merton Miller’s 1977 paper brought a major refinement. While M&M (1963) focused on corporate taxes, Miller highlighted the crucial role of personal taxes paid by investors. Specifically, he noted that:

- Interest income (from bonds or loans) is typically taxed at a higher personal rate (TPi),

- While equity income (via dividends or capital gains) is often taxed at a lower rate (TPe).

Thus, although the firm saves taxes through debt, the investor receiving interest income may lose part of that advantage due to higher personal taxes. Miller argued that the tax benefit of debt is not universal—it depends on the relative tax positions of the firm and its investors.

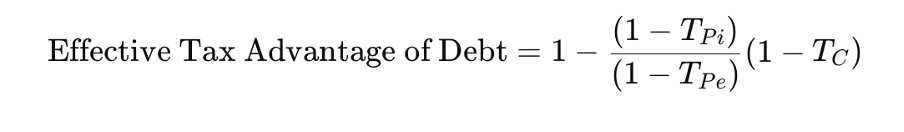

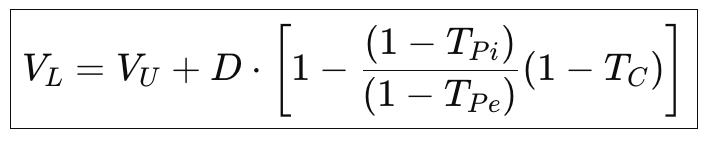

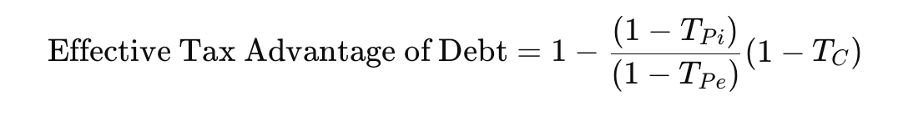

Miller quantified the net tax advantage of debt with the following formula:

where:

- TPi is the personal tax rate on interest income

- TPe is the personal tax rate on equity income (dividends/capital gains)

- Tc is the corporate tax rate

This expression compares the after-tax returns from debt and equity financing, from both the firm’s and investor’s perspectives.

Value of a Levered Firm according to Miller (1977)

In Miller (1977), the value of the firm incorporates both:

1. The corporate tax shield (from M&M 1963), and

2. The personal tax disadvantage from investor taxation on interest income.

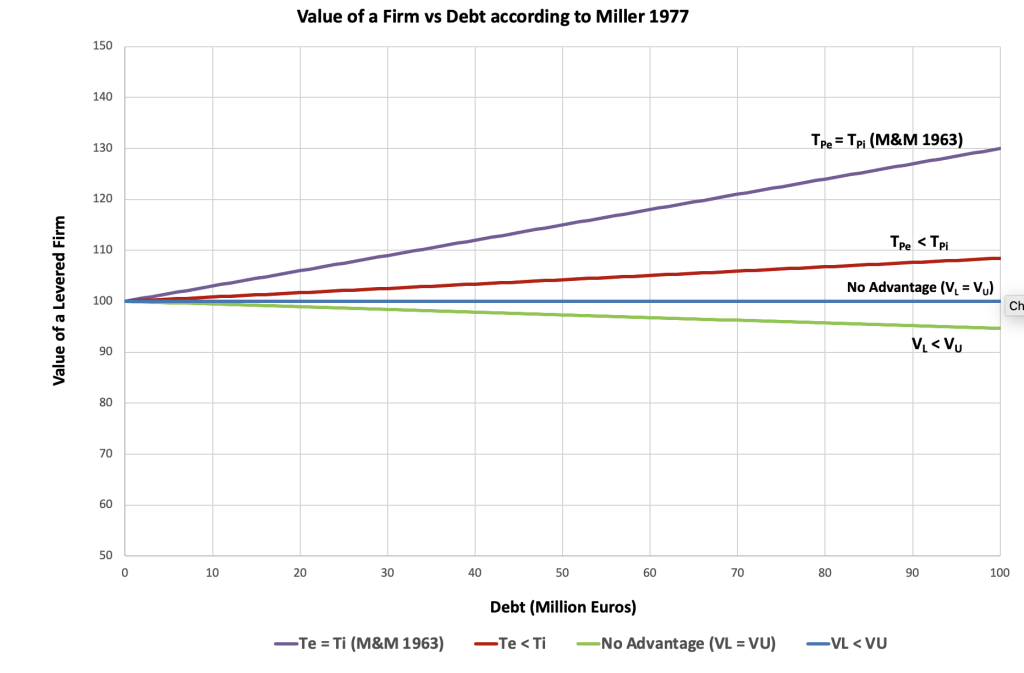

Unlike M&M 1963 (which assumed value keeps increasing with leverage due to tax shields), Miller showed that the firm’s value plateaus at an equilibrium level, reflecting the offsetting effect of personal taxes.

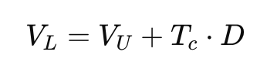

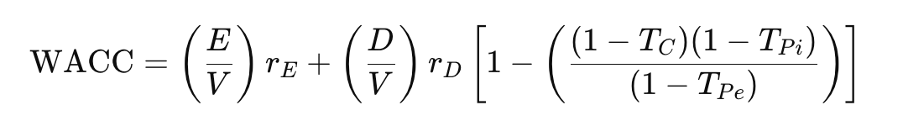

There isn’t a single formula as elegant as in M&M 1963 because Miller focuses on market equilibrium, not firm-level maximization. But we can express the adjusted value of a levered firm relative to the unlevered firm as:

that is,

where:

- VL is the value of a levered firm using debt.

- VU is the value of a unlevered firm not using debt but only equity

- Tc is the Corporate tax rate

- TPi is the personal tax rate on interest income

- TPe is the personal tax rate on equity income (dividends/capital gains)

- D is the amount of debt of the firm

Figure 1. Firm Value vs Debt according to Miller 1977 Theorem

where:

- Tc is the Corporate tax rate

- TPi is the personal tax rate on interest income

- TPe is the personal tax rate on equity income (dividends/capital gains)

The Equilibrium Capital Structure Across Firms

One of the most insightful—and often misunderstood—contributions of Miller (1977) is that there is no single “optimal” capital structure for all firms. Instead of recommending that every company should maximize debt (as M&M 1963 might suggest), Miller argued that the optimal mix of debt and equity depends on the broader market, not just individual firm decisions. His approach introduced a market-level equilibrium perspective, which helps us understand the diverse financing strategies we observe in the real world.

Miller recognized that not all investors are taxed equally. Some investors—like pension funds, endowments, or individuals in low tax brackets—are less affected by taxes on interest income. These investors prefer debt because they can earn stable interest income without facing significant tax penalties. On the other hand, investors in higher tax brackets might favour equity, particularly because capital gains and dividends are often taxed at lower rates than interest income.

This diversity in investor preferences (from different personal tax rates) creates a kind of natural balance in the financial markets. Some firms will issue more debt to attract income-focused investors, while others will rely more on equity to appeal to investors who value capital gains. Over time, this leads to a market equilibrium in which different firms adopt different capital structures based on the preferences of the investors they attract.

In reality, we do not see all firms aggressively using debt to lower their tax bills. Instead, we see some firms—like utilities or financial institutions—using higher levels of debt, while others—like tech startups or growth firms—rely more on equity. This variation observed in practice aligns perfectly with Miller’s theory. The aggregate tax advantage of debt is “used up” across the economy, so not every firm needs to (or should) leverage itself heavily.

Firms essentially compete for investor types, and their capital structure decisions reflect the marginal investor’s personal tax situation. In this way, the equilibrium is not found at the level of a single firm, but across the entire set of firms.

How Miller (1977) Redefined the Cost of Equity and WACC from Modigliani-Miller (1963)

In M&M (1963), the introduction of corporate taxes led to a crucial insight: because interest payments are tax-deductible, debt financing creates a tax shield that reduces the firm’s Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC). The model predicted that, as leverage increases, WACC decreases, and firm value rises—implying that a firm should use as much debt as possible to minimize its cost of capital.

This had a direct impact on the cost of equity as well. In M&M (1963), the cost of equity (rE) increases with leverage to compensate for the rising risk faced by shareholders:

where:

- rE is the cost of equity for a levered firm

- rU is the cost of equity for an unlevered firm

- rD is the cost of debt

- D/E is the debt to equity ratio measuring leverage

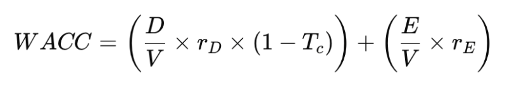

Here, while the cost of equity increases due to higher financial risk, the overall WACC falls, thanks to the tax shield:

Where: V is the Value of the firm (V= D + E)

Miller (1977) introduced personal taxes into the equation—something that M&M (1963) completely ignored. He observed that investors are not only taxed at the corporate level but also at the personal level:

- Interest income is taxed at the personal level (personal tax rate on interest income: TPi)

- Equity dividends and capital gains are taxed at the personal level (personal tax rate on equity: TPe)

Crucially, interest income is taxed more heavily than equity dividends and capital gains: TPi > TPe. This is the case in the United States and most developed countries.

This alters the perceived tax advantage of debt as the benefit of corporate tax deductibility may be neutralized—or even outweighed—by the higher taxes on interest income.

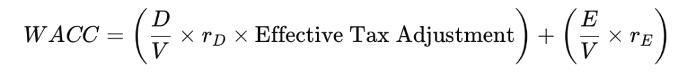

While Miller (1977) didn’t give a neatly adjusted cost of equity formula like Modigliani and Miller (1963), he did show that the tax advantage of debt financing is not universal—it depends on both corporate and personal tax rates. This led to a redefinition of the net tax advantage of debt, which in turn affects WACC:

And so, the adjusted value of the tax shield, and by extension the impact of debt on WACC, becomes:

Using this expression, the WACC becomes:

where,

- Tc is the Corporate tax rate

- TPi is the personal tax rate on interest income

- TPe is the personal tax rate on equity income (dividends/capital gains)

- D/V is the proportion of debt in the capital structure

- E/V is the Proportion of equity in the capital structure

- rE is the cost of equity for a levered firm

- rD is the cost of debt

This means that the WACC no longer declines indefinitely with debt. Instead, as the tax burden on interest income increases (via Ti ), the marginal benefit of debt diminishes. At market equilibrium, the advantage of debt disappears, and WACC flattens—explaining why we observe moderate, not extreme, debt usage in practice.

- If Ti > Te and corporate tax Tc is high, debt still offers a net tax advantage, though smaller than in M&M (1963).

- If the term in brackets equals zero, there is no net tax advantage—WACC remains flat regardless of leverage.

- If the term becomes negative, equity becomes more tax-efficient, and adding debt raises the WACC.

Why Should I Be Interested in This Post?

In corporate finance, the debate around how much debt a firm should take on is far from settled. While traditional models like Modigliani-Miller (1963) emphasize the tax benefits of debt, they ignore the taxes investors pay. This post introduces the groundbreaking Miller (1977) framework, which shows how personal taxes can offset corporate tax advantages, reshaping our understanding of optimal capital structure. If you’re a finance student, investor, or aspiring professional, understanding this equilibrium-based view will give you a more realistic—and nuanced—perspective on how real-world firms decide between debt and equity.

Related posts on the SimTrade blog

▶ Snehasish CHINARA Optimal capital structure with taxes: Modigliani and Miller 1963

▶ Snehasish CHINARA Optimal capital structure with no taxes: Modigliani and Miller 1958

▶ Snehasish CHINARA Solvency and Insolvency in the Corporate World

▶ Snehasish CHINARA Illiquidity, Liquidity and Illiquidity in the Corporate World

▶ Snehasish CHINARA Illiquidity, Solvency & Insolvency : A Link to Bankruptcy Procedures

▶ Snehasish CHINARA Chapter 7 vs Chapter 11 Bankruptcies: Insights on the Distinction between Liquidations & Reorganisations

▶ Snehasish CHINARA Chapter 7 Bankruptcies: A Strategic Insight on Liquidations

▶ Snehasish CHINARA Chapter 11 Bankruptcies: A Strategic Insight on Reorganisations

▶ Akshit GUPTA The bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers (2008)

▶ Akshit GUPTA The bankruptcy of the Barings Bank (1996)

▶ Anant JAIN Understanding Debt Ratio & Its Impact On Company Valuation

Useful resources

Academic research

Miller, M. H. (1977) Debt and Taxes, Journal of Finance, 32(2), 261–275.

Modigliani, F., M.H. Miller (1958) The Cost of Capital, Corporation Finance and the Theory of Investment, American Economic Review, 48(3), 261-297.

Modigliani, F., M.H. Miller (1963) Corporate Income Taxes and the Cost of Capital: A Correction, American Economic Review, 53(3), 433-443.