In this article, Snehasish CHINARA (ESSEC Business School, Grande Ecole Program – Master in Management, 2022-2025) explores the vital difference between solvency and insolvency—where solvency signals long-term financial health, and insolvency marks a tipping point of distress. Understanding this divide is key to assessing corporate resilience and recovery.

Introduction to Solvency and Insolvency

Solvency refers to the ability of a company to meet its long-term financial obligations and sustain operations over time. It is a measure of financial stability that reflects whether an entity’s total assets exceed its total liabilities, providing a buffer to absorb financial shocks or downturns. A solvent company is one that not only meets its short-term obligations (liquidity) but also maintains a robust capital structure for the long haul.

Insolvency occurs when a company is unable to meet its financial obligations as they come due. This may stem from either insufficient liquidity (cash flow insolvency) or a situation where liabilities exceed assets (balance sheet insolvency). Insolvency is a critical financial distress signal and, if unresolved, can lead to bankruptcy, restructuring, or liquidation.

Key Indicators of Solvency

Assessing solvency requires robust financial metrics that provide insight into a company’s long-term financial stability and its ability to meet obligations. Here are the primary indicators used to evaluate solvency:

Solvency Ratios

Solvency ratios measure a company’s financial leverage and its capacity to sustain operations while servicing debt and other long-term obligations. These ratios are pivotal for stakeholders to evaluate financial resilience.

1. Current Ratio

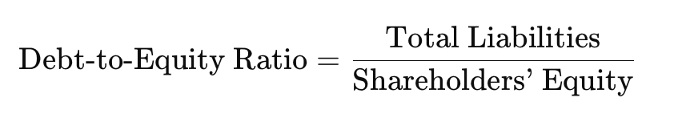

- Purpose: Measures the proportion of debt versus equity in a company’s capital structure.

Interpretation:

- A higher ratio indicates higher reliance on debt, increasing financial risk.

- A lower ratio suggests a more conservative and stable financial structure.

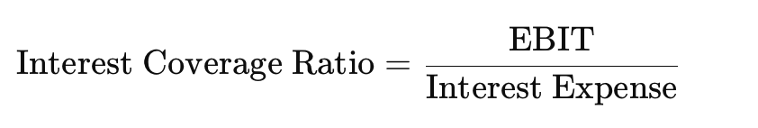

2. Interest Coverage Ratio:

- Reflects the company’s ability to cover its interest payments using earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT).

- A ratio above 2 is generally considered healthy, indicating sufficient earnings to cover interest expenses.

- A ratio below 1 signals that the company may struggle to meet interest obligations.

Cash Flow Analysis

Cash flow analysis evaluates whether a company generates enough cash from its operations to sustain long-term commitments. Unlike profits, cash flows reflect the actual inflow and outflow of money, providing a clearer picture of financial health.

1. Operating Cash Flow (OCF):

- Indicates the cash generated from core business operations.

- Key Metric: Positive and consistent OCF suggests strong financial health.

- Example: A manufacturing firm with consistent OCF can comfortably reinvest in growth or repay long-term debt.

2. Free Cash Flow (FCF):

Free Cash Flow = Operating Cash Flow−Capital Expenditure

Free Cash Flow = EBIT × (1−Tax Rate) + Depreciation and Amortization − Change in Working Capital − Capital Expenditures

- Reflects the cash available for distribution to shareholders or debt repayment after maintaining capital assets.

- Example: A company with growing FCF can fund expansion or pay down debt without raising additional capital.

Balance Sheet Strength

The balance sheet provides a snapshot of a company’s financial position, highlighting its solvency through the relationship between assets, liabilities, and equity.

1.Net Asset Value (NAV):

Net Asset Value=Total Assets−Total Liabilities

- Purpose: Indicates the residual value of a company’s assets after all liabilities are settled.

- Interpretation: A positive NAV reflects solvency, while a negative NAV signals financial distress.

- Example: Companies with high NAV relative to liabilities are perceived as stable and creditworthy.

2.Asset Quality and Liquidity:

- High-quality assets (e.g., cash, receivables) contribute to solvency by being easily convertible into cash during a crisis.

- Illiquid or depreciating assets, such as specialized machinery, may erode financial strength.

3.Leverage and Capital Structure:

- A balance sheet with excessive liabilities compared to equity may indicate solvency risks.

- Strong equity reserves act as a cushion against unforeseen losses.

Types of Insolvency

Insolvency is a critical financial condition indicating that a company or individual is unable to meet its financial obligations. It is broadly categorized into Cash Flow Insolvency and Balance Sheet Insolvency, each reflecting distinct dimensions of financial distress. Understanding these types is essential for diagnosing financial health and determining appropriate remedies.

Cash Flow Insolvency

Cash flow insolvency occurs when an entity is unable to meet its immediate or short-term financial obligations as they come due, even though its assets may exceed its liabilities. This situation often arises from liquidity issues rather than an inherent lack of financial stability.

Key Characteristics:

- The entity has sufficient assets but lacks the liquid resources to convert them into cash quickly enough to pay its debts.

- Typically a temporary condition that can be resolved through effective liquidity management or short-term financing.

Causes:

- Poor cash flow management (e.g., delayed collections, excessive inventory buildup).

- Seasonal business cycles with uneven cash inflows and outflows.

- Overreliance on credit for operational expenses without adequate cash reserves.

- External factors such as economic downturns or disruptions in supply chains.

Balance Sheet Insolvency

Balance sheet insolvency arises when an entity’s total liabilities exceed its total assets, resulting in negative net worth. This form of insolvency reflects deeper financial distress, often signalling a fundamental mismatch between a company’s obligations and its overall financial resources.

Key Characteristics:

- Indicates that the entity is technically insolvent and unable to repay its debts even if all assets are liquidated.

- Unlike cash flow insolvency, this condition is structural and often requires extensive restructuring or bankruptcy proceedings.

Causes:

- Persistent losses that erode retained earnings and equity over time.

- Excessive borrowing relative to the company’s capacity to generate revenue.

- Depreciation in the value of long-term assets, particularly in industries reliant on physical or specialized assets (e.g., real estate or heavy machinery).

- External shocks such as regulatory changes, market collapses, or catastrophic events.

Causes of Insolvency

Insolvency arises from a combination of factors that undermine a company’s ability to meet its financial obligations over the long term. Below are the primary causes of insolvency:

- Prolonged Financial Losses – Sustained operational losses over time erode a company’s equity and reduce its ability to generate profits. Businesses operating in highly competitive or declining markets may struggle to maintain profitability, leading to negative net income and a weakened financial position.

- Excessive Leverage – Over-reliance on borrowed funds (debt) can strain a company’s financial stability. High leverage increases fixed costs in the form of interest payments, reducing financial flexibility. If the company’s revenues are insufficient to cover these obligations, insolvency becomes inevitable.

- Poor Financial Management – Inadequate budgeting, weak internal controls, or mismanagement of resources can lead to insolvency. Companies that fail to monitor expenses, optimize revenue streams, or manage working capital effectively are at higher risk of insolvency.

- Decline in Market Demand – Shifts in consumer preferences, technological advancements, or market disruptions can lead to reduced demand for a company’s products or services. Persistent declines in revenue can deplete reserves and make it difficult to cover fixed costs and debt obligations. Adverse Economic Conditions – Broader economic downturns, recessions, or geopolitical uncertainties can reduce consumer spending and disrupt supply chains. These factors often lead to declining revenues and increased costs, pushing businesses into insolvency.

- Legal and Regulatory Challenges – Ongoing legal disputes, fines, or changes in regulatory requirements can drain financial resources and disrupt operations. Companies facing substantial penalties or compliance costs may become insolvent if they lack sufficient reserves.

- Poor Capital Structure – An imbalance in the capital structure, such as an over-reliance on short-term debt for funding long-term projects, can increase financial risk. Companies that fail to optimize their mix of debt and equity may struggle with rising interest payments and reduced operational flexibility.

- Unanticipated Large Expenses – Unexpected financial burdens, such as lawsuits, product recalls, or natural disasters, can quickly deplete a company’s reserves and lead to insolvency.

- Inefficient Business Model -Companies with outdated or inefficient business models may fail to generate sufficient returns to sustain operations, especially in competitive or innovative markets.

Consequences of Insolvency

Insolvency has far-reaching implications for businesses, creditors, employees, and other stakeholders. Below are the primary consequences of insolvency:

- Bankruptcy Filings -Insolvency often leads to legal proceedings, with the most common being bankruptcy filings. Depending on the jurisdiction, companies may choose between different bankruptcy types:

- Chapter 7 (Liquidation): The company ceases operations, and its assets are sold to pay creditors. This is common for businesses that have no viable path to recovery.

- Chapter 11 (Reorganization): The company continues operations while restructuring its debts and obligations under court supervision. This allows businesses to renegotiate terms with creditors and emerge as a leaner, more viable entity.

- Restructuring or Liquidation of Assets -Companies may undergo significant restructuring to restore financial stability. This can include renegotiating debt terms, cutting operational costs, or divesting non-core assets.

- Restructuring: Focuses on reorganizing the company’s financial obligations to regain solvency while maintaining operations.

- Liquidation: Involves selling off assets to repay creditors, often signalling the end of business operations.

- Loss of Shareholder Value – Shareholders are often the last to be compensated in insolvency scenarios, and in many cases, they lose their entire investment. The market value of the company’s shares typically plummets during insolvency proceedings, reflecting the financial instability.

- Reputational Damage – Insolvency erodes trust among stakeholders, including creditors, investors, customers, and suppliers. This damage to reputation can make it challenging for a company to secure future financing, partnerships, or business opportunities even after recovery.

- Employee Layoffs and Salary Defaults – Insolvent companies often reduce their workforce to cut costs. Employees may face delayed salaries, loss of benefits, or sudden termination. This can create significant disruptions for the workforce and impact morale and productivity.

- Legal and Regulatory Implications – Insolvency proceedings often involve legal scrutiny, with courts, regulatory bodies, and creditors closely examining the company’s financial activities. Non-compliance or mismanagement that contributed to insolvency can lead to fines, penalties, or criminal charges against executives.

- Asset Seizure by Creditors – Creditors may take legal action to recover debts, resulting in the seizure or foreclosure of the company’s assets. Secured creditors typically have priority in claiming collateral, while unsecured creditors may receive partial or no repayment.

- Impact on Creditors – Creditors may face financial losses due to unpaid debts. In bankruptcy, the repayment hierarchy often prioritizes secured creditors, leaving unsecured creditors with minimal recovery. This can lead to a ripple effect on creditors’ financial health.

- Industry and Market Implications – Insolvency of a major company can disrupt the industry or supply chain it operates in. For example, the bankruptcy of a large supplier may affect dependent companies downstream, creating broader economic consequences.

- Opportunities for Acquisition or Takeover – Insolvency often leads to opportunities for competitors or investors to acquire assets or the entire company at discounted valuations. This can result in consolidation within the industry.

Preventing Insolvency

Proactively managing financial health is the cornerstone of preventing insolvency. Businesses must employ strategic measures to anticipate potential risks, optimize resources, and build resilience against economic uncertainties.

Importance of Financial Forecasting and Stress Testing

Financial Forecasting: Regular financial forecasting allows businesses to predict future cash flows, revenue, and expenses. Accurate forecasts enable companies to identify potential shortfalls well in advance and implement corrective measures.

Key Actions:

- Develop rolling forecasts that adjust for real-time changes.

- Incorporate multiple scenarios to evaluate outcomes under varying conditions.

Example: A company anticipating seasonal revenue dips can arrange short-term financing or delay non-essential expenses.

Stress Testing: Stress testing simulates adverse economic scenarios—such as a market downturn, supply chain disruption, or rising interest rates—to evaluate the company’s ability to remain solvent under pressure.

Key Actions:

- Assess liquidity under stress scenarios to determine if obligations can be met.

- Use outcomes to refine contingency plans.

Example: A manufacturer testing the impact of a 20% raw material cost increase might discover a need for improved supplier contracts.

Effective Debt Management Strategies

Debt Structuring: Avoid excessive reliance on short-term debt, which can strain cash flows. Use a balanced mix of short-term and long-term debt to align with business cycles and asset lifespans.

Key Actions:

- Renegotiate unfavourable loan terms.

- Use fixed-rate loans during periods of volatile interest rates.

Debt Servicing Discipline:

Prioritize timely repayment of interest and principal to avoid compounding liabilities.

Example: Automating debt payments ensures consistency and avoids penalties.

Monitoring Debt Ratios:

Regularly analyse debt-to-equity and interest coverage ratios to ensure sustainable leverage.

Key Actions:

- Reduce non-essential borrowing.

- Use retained earnings or equity to finance expansion instead of debt.

Building Strong Liquidity Buffers

Liquidity Reserves:

Maintain cash reserves or liquid assets to manage unexpected shortfalls. A robust liquidity buffer acts as a financial safety net during crises.

Key Actions:

- Allocate a percentage of revenue to a contingency fund.

- Invest in low-risk, short-term instruments like treasury bills.

Credit Line Management:

Establish pre-approved credit facilities for emergency use.

Example: A revolving credit line ensures access to immediate funding without lengthy approval processes.

Working Capital Optimization:

Efficiently manage receivables, payables, and inventory to free up cash.

Example: Implementing stricter credit terms for customers and negotiating extended payment terms with suppliers.

Why Should I Be Interested in This Post?

Insolvency is not just a business concern; it’s a fundamental challenge that can impact investors, employees, and entire economies. This post equips you with a comprehensive understanding of how to anticipate, prevent, and address insolvency by exploring its causes, indicators, and solutions. Whether you’re a student aspiring to master corporate finance, an entrepreneur striving to protect your business, or a professional managing financial risks, the insights in this article empower you to navigate financial complexities with confidence. By understanding solvency dynamics and adopting proactive strategies, you can make informed decisions, safeguard financial stability, and capitalize on opportunities, even in the face of adversity.

Related posts on the SimTrade blog

▶ Snehasish CHINARA Illiquidity, Liquidity and Illiquidity in the Corporate World

▶ Snehasish CHINARA Illiquidity, Solvency & Insolvency : A Link to Bankruptcy Procedures

▶ Snehasish CHINARA Chapter 7 vs Chapter 11 Bankruptcies: Insights on the Distinction between Liquidations & Reorganisations

▶ Snehasish CHINARA Chapter 7 Bankruptcies: A Strategic Insight on Liquidations

▶ Snehasish CHINARA Chapter 11 Bankruptcies: A Strategic Insight on Reorganisations

▶ Akshit GUPTA The bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers (2008)

▶ Akshit GUPTA The bankruptcy of the Barings Bank (1996)

▶ Anant JAIN Understanding Debt Ratio & Its Impact On Company Valuation