In this article, Andrei DONTU (ESSEC Business School, Global Bachelor in Business Administration (GBBA) 2025-2026) explains the gap between the productivity gains and the unrealized returns of the investors regarding the investments in AI.

Introduction

In the current market landscape, “Artificial Intelligence” has become the magic word used to justify almost any valuation. The narrative is simple: AI will trigger a productivity explosion, fundamentally altering the unit economics of global business and ushering in a new era of equity growth. However, when we cut away the marketing icing and look at the underlying economic data, a much more sobering economic reality emerges, one that I call the AI Productivity Myth.

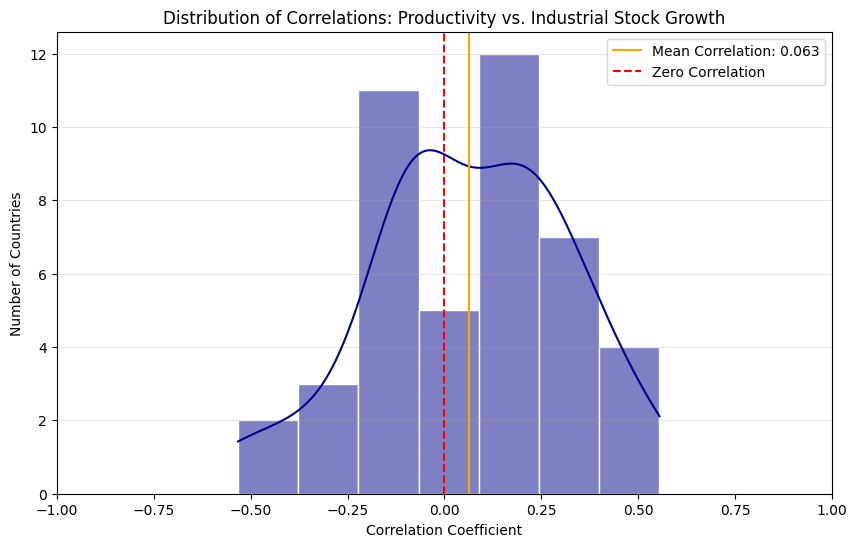

Distributions of Correlations: Stock Growth vs Industrial Stock Growth

Source: ECB data.

The core of this myth is the macroeconomic assumption that a more efficient workforce naturally results in a more valuable stock market. This myth has been debunked on numerous occasions(1) (2), but the disruption created by AI creates new challenges that have to be addressed. To test this, I conducted an extensive analysis on the correlation between labor productivity and stock market returns across European Union countries. The results were startling. The correlation value was only 0.063.

The 0.063 Reality Check

In the world of statistics, a correlation of 0.063 is effectively zero. This figure reveals a profound “missing link” in our economic understanding. For decades, workers in the EU became more efficient and had almost no direct impact on the country’s stock market performance.

In conducting this study, I took the data for the EU member states starting from 2005 until 2025. This time-lapse represents the period following the “.com bubble” and the beginning of the mass adoption of informational systems by many companies. As the cost of owning, operating, and managing these systems became more accessible, it represented a fresh start.

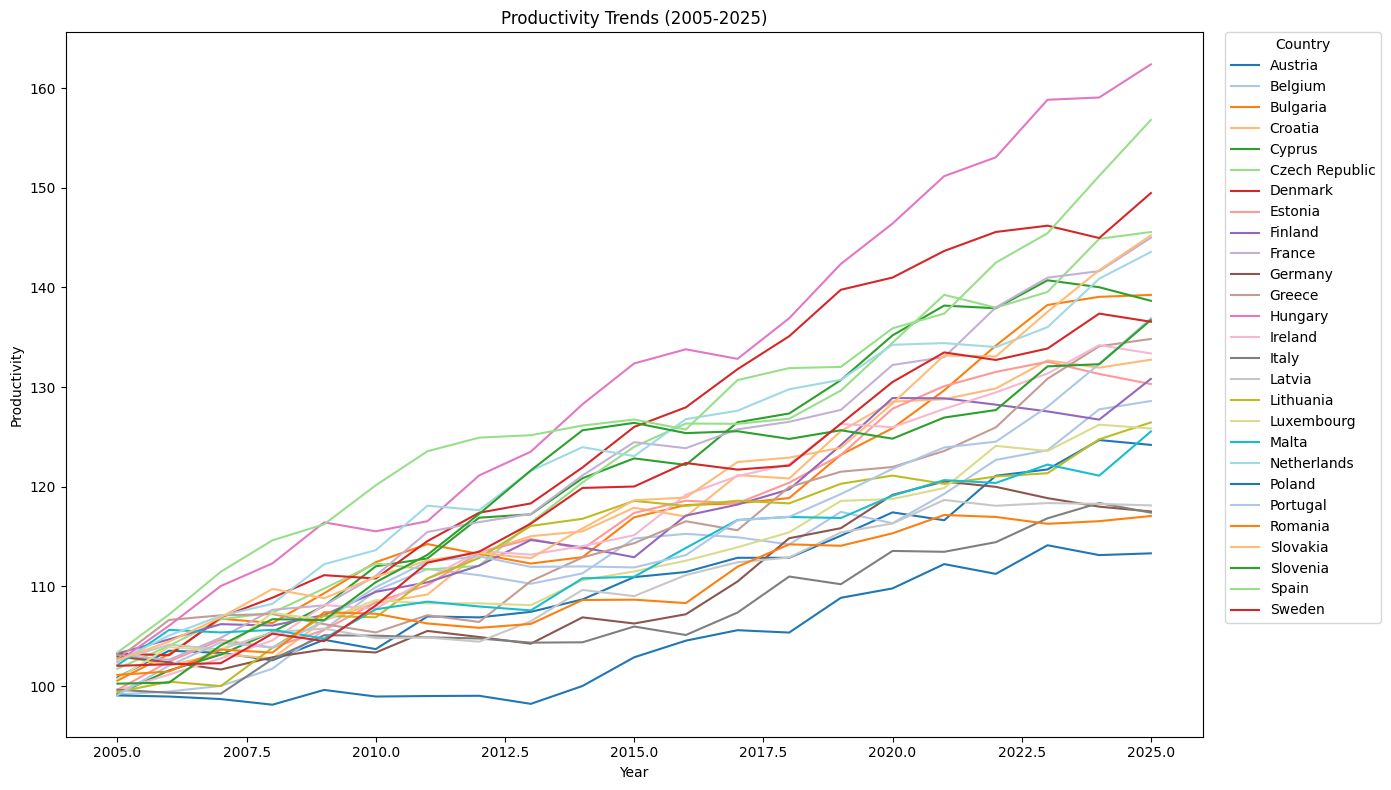

Productivity Trend

Source: ECB data.

By computing the productivity with the return on the EURO STOXX, a clear result can be seen: working harder is not making the enterprise more valuable if everyone is capable of implementing similar strategies. At an individual level, some countries can excel in the implementation if the governance facilitates the projection of technology by liberating and promoting innovation. Some good examples would be the Netherlands, a leader in innovation in the technology and information sector, benefiting heavily from the adoption of the internet and outsourcing, and Italy, a counter-example in productivity growth with similarly low growth in the stock market.

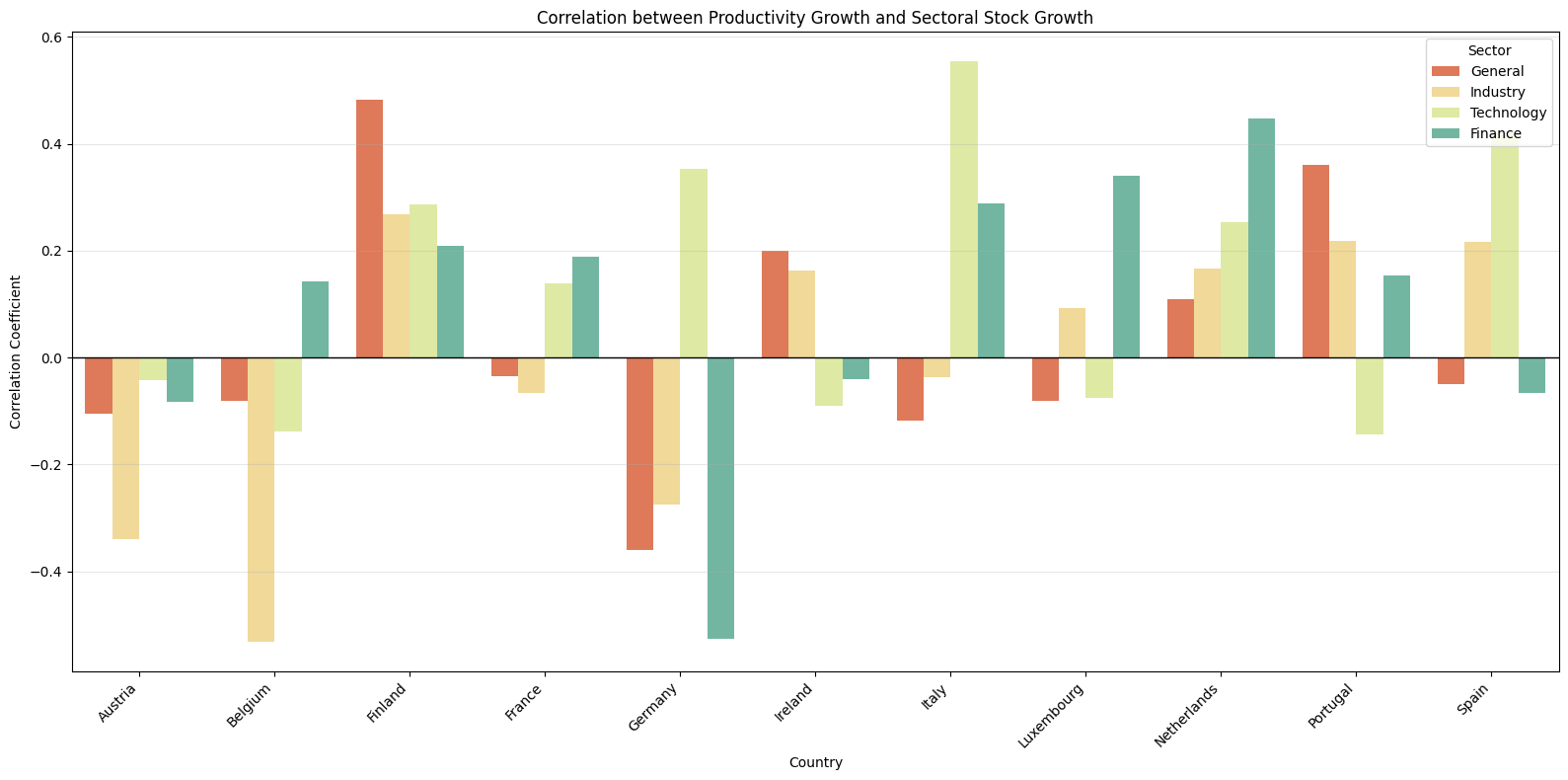

Sectoral Correlation

Source: ECB data.

Although many countries exhibit a significant correlation between growth and productivity, the reality shows that some sectors are driving the general growth. The benefits of the new technologies implemented in the information sector led to a process simplification, reducing the due diligence and accelerating the globalization of the product and market access. While some sectors directly benefited from the implementation of the internet in the processes, the industrial process lagged in showing a similar impact from the internet adoption.

The implementation of the internet resulted in winners and losers, affecting individual companies differently and consolidating the position of global leaders in the industry. Following the .com bubble, many companies disappeared or were acquired by the companies that successfully bypassed the fast-paced changes of the new demands of the customers that encountered a truly global world for the first time (3).

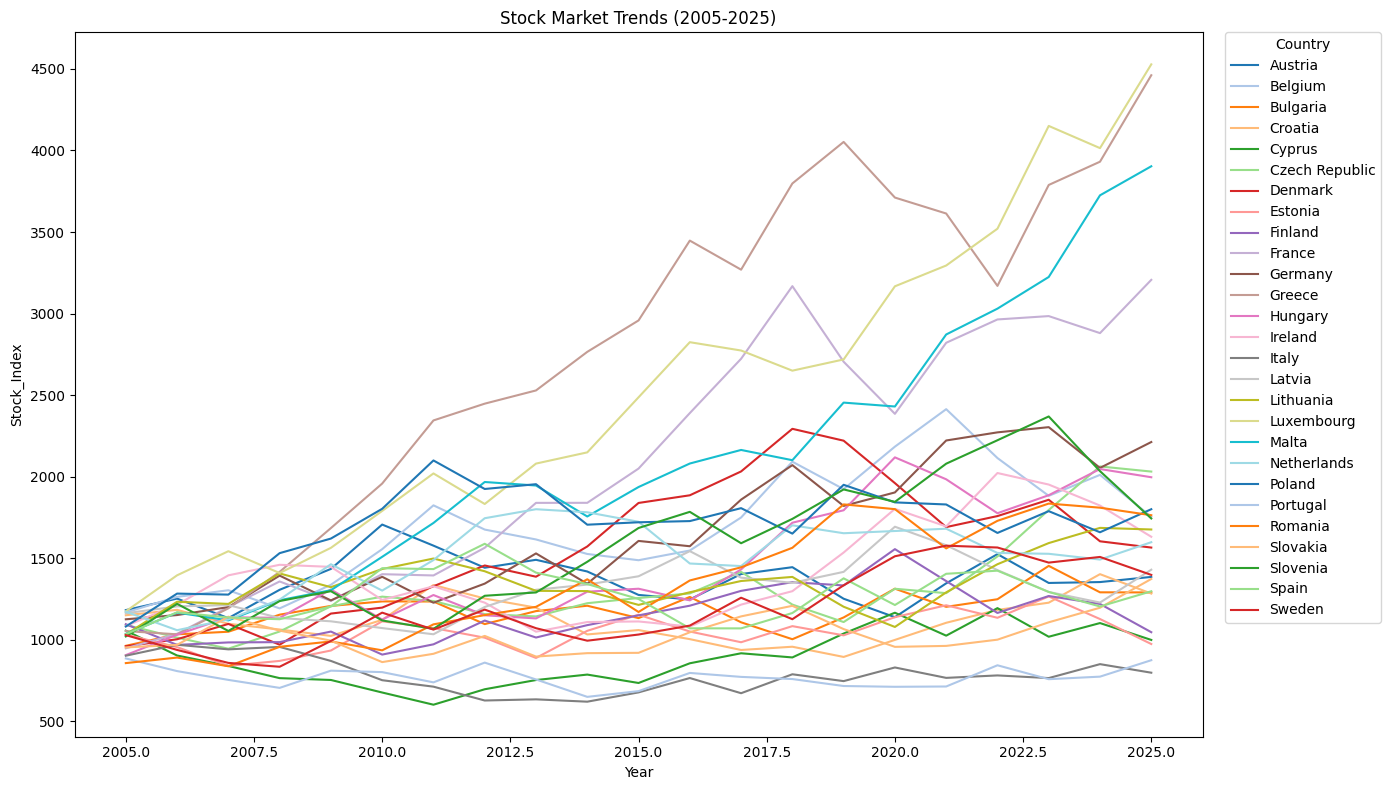

Stock Market Trends

Source: ECB data.

This finding is the “missing link” for the AI Productivity Myth. If thirty years of digital and industrial evolution failed to bridge this gap, investors must ask why AI will be the exception and close the gap. My research suggests that productivity is a measure of how hard an economy works, whereas stock growth is a measure of how much of that work shareholders actually get to keep. In the EU, these two variables operate in parallel universes and vary vastly from one country to another.

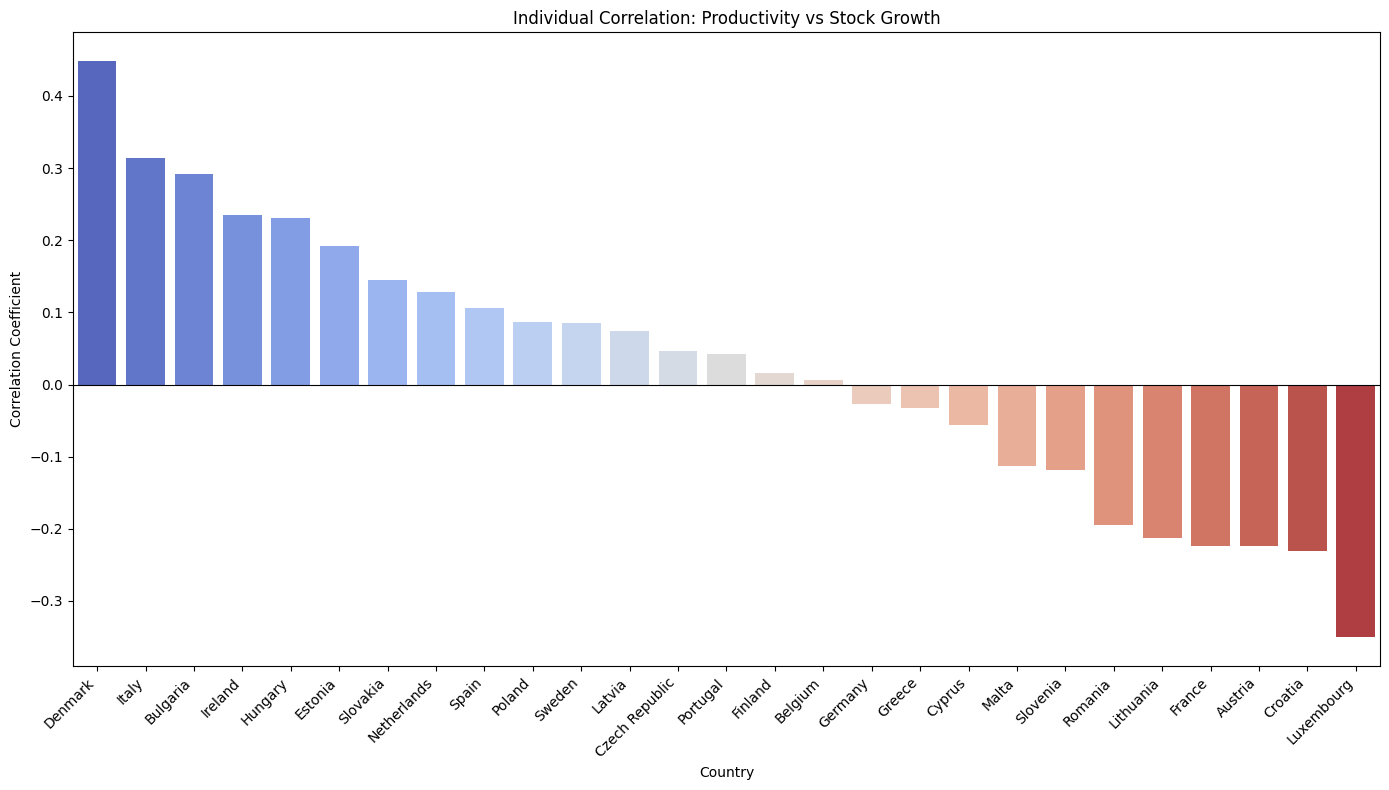

Individual Correlation: Productivity vs Stock Growth

Source: ECB data.

Echoes of the Internet Boom

In the late 1990s, the Internet was the “disruptive power” that promised a new era of high profits from internet sales, showing positive sentiment in the new technology (4). Specialists discussed the exponential implementation of the internet and how all companies will use it in maximizing their profits and directly impacting the prices of the stocks. Many investors were unaware of the risk involved in the investments in new technologies, and focused solely on the possible returns from their investments. The promise was very similar to the AI’s, the internet will revolutionize the world, creating a massive leap in how we exchange information.

Although the information travelled faster and everyone was benefiting from the effects of a “smaller world”, it backfired. While the technology succeeded, the investments often failed. When the bubble burst in 2000, it wasn’t because the internet stopped working; it was because the market momentum had far outpaced the actual ability of companies to turn that efficiency into profit.

Today, AI is facing the same exaggerated expectations. Investors are paying premium prices for the hope of future productivity, but they are ignoring thehardships of the adoption gap: the period where companies spend billions on Graphic Processing Units(GPU), the core of the AI systems, and energy without seeing a single cent of increased margin. This gold rush after the current stock of GPUs is leading to a speculative movement over their importance and short product cycles, leading to slow amortizations for ⅚ years, while in reality they become obsolete in ⅔ years(5).

The “Blurriness” of AI Returns

The “blurriness” of Large Language Models (LLMs) refers to the difficulty in measuring their return on investment (ROI). The investment in AI chips, developing agents, and managing data centers comes into effect without prior benchmarks on how such investments should be estimated, and it is hard to quantify their success in monetary terms or advantages against the competitors. Unlike a new factory machine that produces 10% more widgets, an LLM’s impact on knowledge and streamlining is harder to capture on a balance sheet.

- The CapEx Trap: Companies are engaged in an “Arms Race,” spending record amounts on infrastructure. Firms are paying considerable amounts on implementation costs (licensing, retraining, power, cloud, cybersecurity,etc.), but often eats up the savings the AI was supposed to generate.

- The Perfect Competition Paradox: If every firm uses AI to work 50% faster, no single firm has a competitive advantage. Competition forces them to lower prices, passing the productivity gain to the consumer while the investor is left with higher tech costs and lower retention of both earnings and customers.

- Front-Running the Gains: The stock market is forward-looking. Most expected gains are already baked into today’s prices. When a company finally reports a “good” productivity increase, the stock may drop because it wasn’t the “miraculous” increase the market demanded to justify its valuation.

Conclusion: Why the Low Correlation Matters

The key takeaway is the danger of the 0.063 correlation. It proves that efficiency is the tool for survival, but not a guaranteed engine for wealth. In the European Union (EU), efficiency gains are frequently absorbed by regulatory compliance, labor costs, and competitive pricing before they ever reach the bottom line.

Why should I be interested in this post?

As we move through 2026, the “blurriness” of AI will likely resolve into a clear picture of high costs and incremental gains. For everyone, the lesson should be clear: do not mistake a technological revolution for a guaranteed stock market return. In an environment where the correlation between productivity and returns is as low, the “AI Myth” is a luxury that few can afford to believe in.

Other SimTrader Blogs:

▶ Mahé FERRET Behavioral Finance

References

(1) Chun, H., Kim, J. W., & Morck, R. (2016). Productivity growth and stock returns: firm-and aggregate-level analyses. Applied Economics, 48(38), 3644-3664.

(2) Pellegrini, C. B., Romelli, D., & Sironi, E. (2011). The impact of governance and productivity on stock returns in European industrial companies. Investment management and financial innovations, (8, Iss. 4), 20-28.

(3) Johansen, A., & Sornette, D. (2000). The Nasdaq crash of April 2000: Yet another example of log-periodicity in a speculative bubble ending in a crash. The European Physical Journal B-Condensed Matter and Complex Systems, 17(2), 319-328.

(4) Bandyopadhyay, S., Lin, G., & Zhang, Y. (2001). A critical review of pricing strategies for online business models.

(5) Lifespan of AI chips- the 300 billion question

Data sources:

European Central Bank EURO STOXX

European Central Bank~Productivity Growth

About the author

The article was written in January 2026 by Andrei DONTU (ESSEC Business School, Global Bachelor in Business Administration (GBBA), 2025-2026).

▶ Read all posts written by Andrei DONTU