In this article, Dawn DENG (ESSEC Business School, Global Bachelor in Business Administration (GBBA), Smith-ESSEC Double Degree Program, 2024-2026) offers a practical introduction to building a beginner-friendly stock pitch—from selecting a company you truly understand, to structuring the investment thesis, and translating logic into valuation. The goal is not to produce “perfect numbers,” but to make your reasoning coherent, transparent, and testable.

Why learn to do a stock pitch?

Learning to pitch a stock is learning to tell a story in financial language. Whether you are aiming at investment banking, asset management, or equity research roles—or competing in a student investment fund—the stock pitch is a core exercise that reveals both how you think and how you communicate. Within ten minutes, you must answer three questions: Who is this company? Why is it worth investing in? And how much is it worth? A strong pitch convinces not by breadth of information, but by reasoning that is consistent, evidence-based, and verifiable.

Choosing a company: balance understanding and interest

For beginners, picking the right company matters more than picking the right industry. Do not start by hunting the next “multibagger.” Start with a business you can truly explain: how it makes money, who its customers are, and what drives its costs. Familiar products and clear business models are your best teachers. I first learned how to build a stock pitch during my Investment Banking Preparatory Program at my home university, Queen’s Smith School of Business. The program was designed to train first- and second-year students in the fundamentals of financial modeling, valuation, and investment reasoning. In my first pitch with the audience from school investment clubs and the professor, I chose L3Harris Technologies (NYSE: LHX)—working across defense communications and space systems. Its complexity pushed me to locate it precisely in the value chain: not a weapons maker, but a critical node in command-and-control. No valuation model can substitute that kind of business understanding.

Industry analysis: space, structure, and cycle

The defense sector operates under multi-year budget cycles, long procurement timelines, and high barriers to entry. The market is dominated by five major U.S. contractors—Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, General Dynamics, Raytheon, and L3Harris. While peers tend to focus on platform manufacturing, L3Harris differentiates itself through integrated communication and command systems, giving it recurring revenue and a lighter asset base. This focus positions the company at the intersection of AI-driven defense innovation and space-based data systems—a niche expected to grow rapidly as military operations become more network-centric.

Investment thesis: three key arguments

(1) Strategic Layer – “Why now”

The defense industry is entering a new digitalization cycle. L3Harris’s acquisition of Aerojet Rocketdyne expands its vertical integration into propulsion and guidance, while its strong exposure to secure communication networks aligns with rising defense budgets for AI and satellite modernization.

(2) Competitive Layer – “Why this company”

Compared to peers, L3Harris demonstrates strong operational efficiency and disciplined capital allocation. Its EBITDA margin of ~20% and R&D intensity near 4% of revenue outperform sector averages. Management has proven its ability to sustain synergy realization post-merger, reducing leverage faster than expected.

(3) Financial Layer – “Why it matters”

The company’s robust cash generation supports consistent dividend growth and share repurchases, signaling confidence and financial flexibility. Our base-case target price was USD 287, implying ~12% upside, supported by improving free cash flow yield and moderate multiple expansion.

Valuation: turn logic into numbers

Valuation quantifies your logic. At the beginner level, focus on two complementary methods: Relative Valuation and Absolute Valuation (DCF). The first tells you how markets price similar assets; the second estimates intrinsic value under your assumptions. Use them to cross-check each other.

Relative Valuation

We benchmarked L3Harris Technologies against major U.S. defense peers including Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and Raytheon Technologies, using EV/EBITDA and P/E multiples as our key comparative metrics. Peers traded at around 14–16× EV/EBITDA, consistent with the industry’s steady cash-flow profile. However, given L3Harris’s stronger growth visibility, improving free cash flow, and synergies expected from the Aerojet Rocketdyne acquisition, we assigned a justified multiple of 17× EV/EBITDA—positioning it slightly above the sector average. This premium reflects not only its operational efficiency but also its role in the ongoing digital transformation of defense communications and space systems.

Absolute Valuation (Discounted Cash Flow)

DCF values the business as the present value of future free cash flows. Build operational drivers in business terms (volume/price, mix, scale effects), then translate into FCF:

FCF = EBIT × (1 – tax rate) + D&A – CapEx – ΔWorking Capital.

Choose a WACC consistent with long-term capital structure (equity via CAPM; debt via yield or recent financing, after tax). For terminal value, use a perpetual growth rate aligned with nominal GDP and industry logic, or an exit multiple consistent with your relative valuation. Present a range via sensitivity (WACC, terminal growth, margins, CapEx) rather than a single precise point. Where DCF and multiples converge, your target price gains credibility; where they diverge, explain the source—cycle position, peer distortions, or different long-term assumptions.

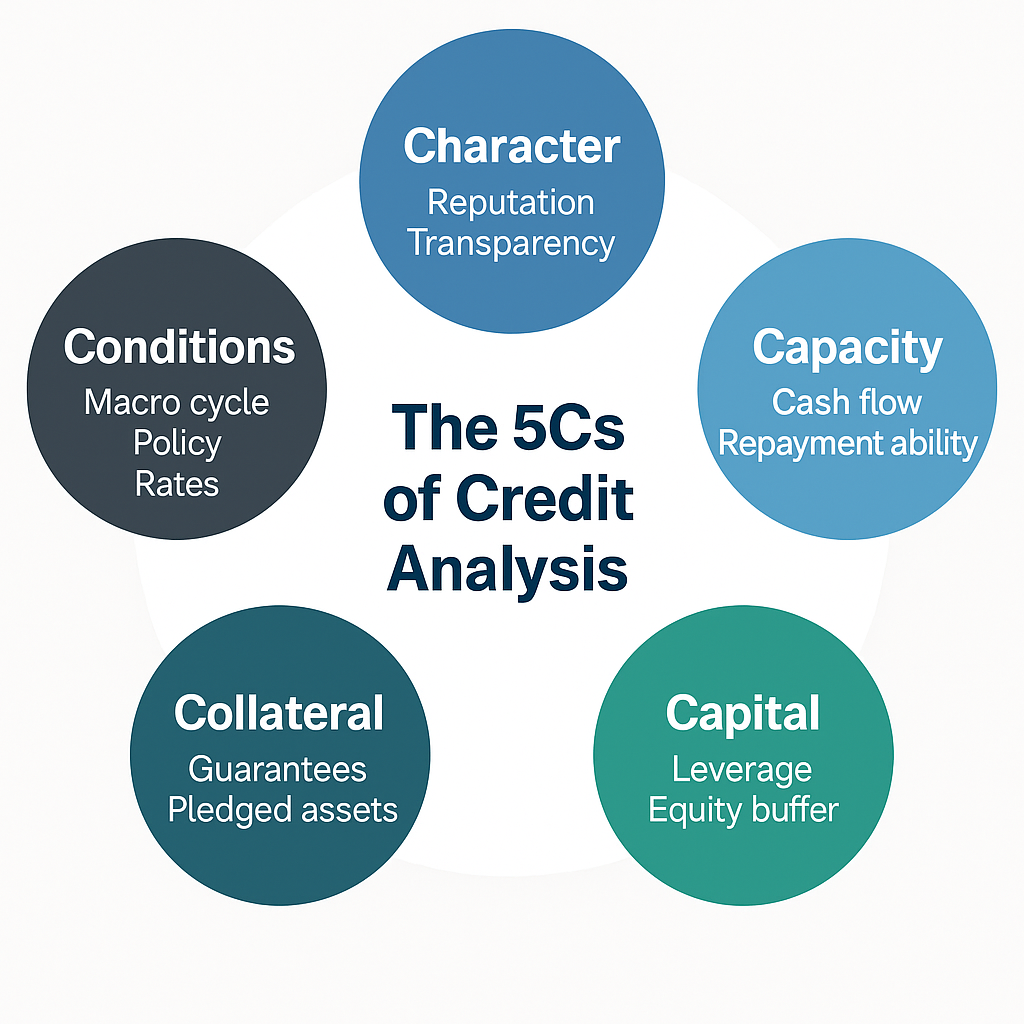

Risks and catalysts: define uncertainty

Every pitch must face uncertainty head-on. Map the fragile links in your logic—macro and policy (rates, budgets, regulation), competition and disruption (new entrants, technology shifts), execution and governance (integration, capacity ramp-up, incentives). Then specify catalysts and timing windows: earnings and guidance, major contracts, launches or pricing moves, structural margin inflections, M&A progress, or regulatory milestones. Make it explicit what would validate your thesis and when you would reassess.

Related posts on the SimTrade blog

▶ Cornelius HEINTZE Two-Stage Valuation Method: Challenges

▶ Andrea ALOSCARI Valuation Methods

▶ Jorge KARAM DIB Multiples Valuation Method for Stocks

Useful resources

Mergers & Inquisitions How to Write a Stock Pitch

Training You Stock Pitch en Finance de Marché : définition et méthode

Harvard Business School Understanding the Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) Method

Corporate Finance Institute Types of Valuation Multiples and How to Use Them

About the author

The article was written in October 2025 by Dawn DENG (ESSEC Business School, Global Bachelor in Business Administration (GBBA), Smith-ESSEC Double Degree Program, 2024-2026).