Posts

In this article, Dawn DENG (ESSEC Business School, Global Bachelor in Business Administration (GBBA), Smith-ESSEC Double Degree Program, 2024-2026) presents a practical framework for assessing a company’s creditworthiness. The analysis integrates both financial and non-financial dimensions of trust, using the classic 5C framework widely adopted in banking and corporate finance.

Why assess creditworthiness

In corporate finance, assessing a company’s creditworthiness lies at the heart of lending, underwriting, and risk management. For banks, it is not only a “yes/no” lending decision (and also the level of interest rate propose to the client); it is a structured way to understand repayment capacity, operating quality, and long-term sustainability. The goal is not to label a company as “good” or “bad,” but to answer three questions: Can it repay? Will it repay? If not, how much can be recovered?

The five pillars of credit analysis: the 5C framework

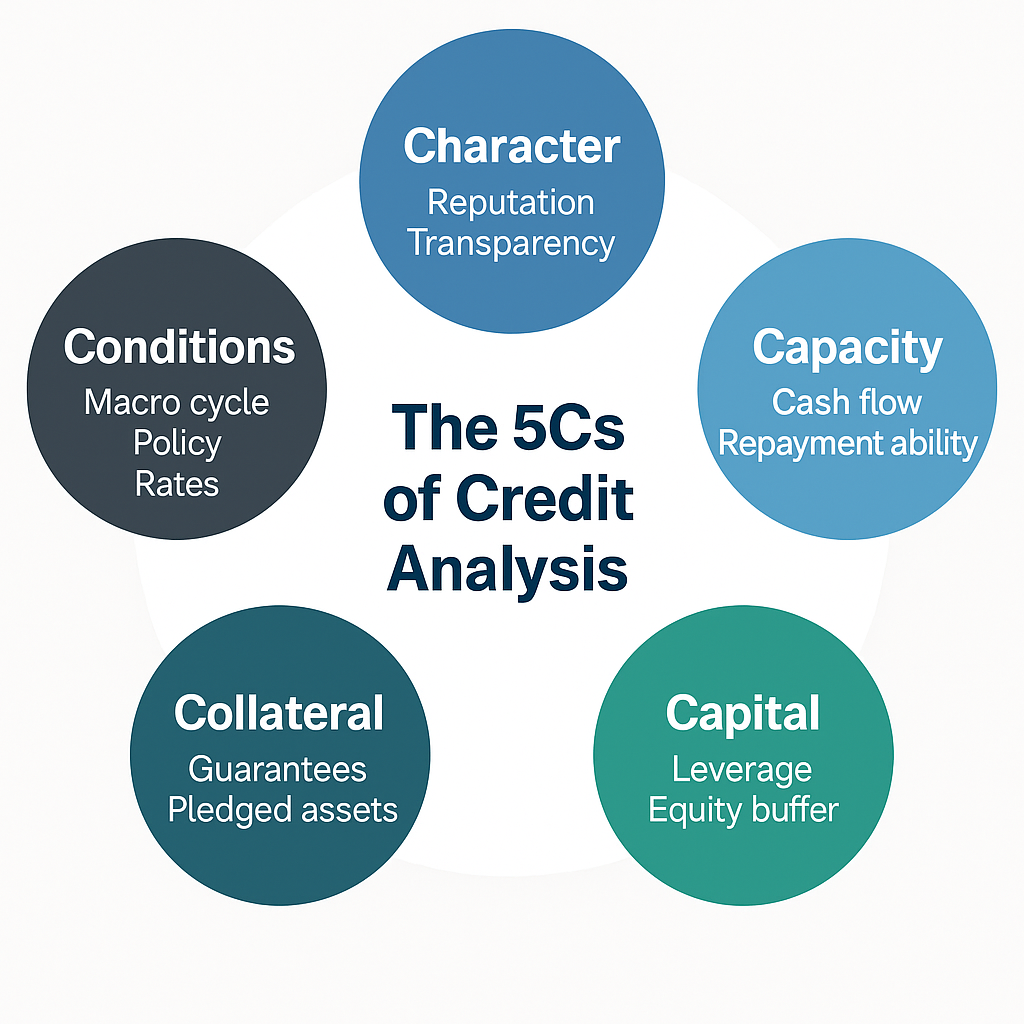

The 5C framework, an industry standard that crystallized over decades of banking practice and supervisory guidance, assesses five core dimensions: Character, Capacity, Capital, Collateral, and Conditions. Rather than originating from a single author or institution, it emerged progressively across lenders’ credit manuals, central-bank training, and regulator handbooks, and is now embedded in banks’ risk-rating and loan-pricing models. These components are interdependent: strength in one area can mitigate weaknesses in another, while vulnerabilities may compound when several Cs deteriorate at the same time.

The five pillars of credit analysis: the 5C framework.

Source: the author.

Character: reputation and track record

Character covers the firm’s reputation and willingness to honor obligations. Analysts review borrowing history, repayment behavior, disclosure practices, management integrity, and banking relationships. A consistent record of timely payments and transparent reporting typically earns a stronger credit score.

For example, a mid-sized manufacturer that consistently meets payment deadlines and maintains transparent reporting will typically be viewed as a low-risk borrower, even if its margins are moderate.

Capacity: ability to repay

Capacity assesses whether operating cash flow can service debt on time. Core indicators include: Interest Coverage (EBIT/Interest), DSCR, and Liquidity ratios (Current/Quick/Cash). As a rule of thumb, an interest coverage below 2× or DSCR below 1.0× often signals liquidity pressure.

For example, in 2023, several property developers in China exhibited DSCR levels below 1.0 amid declining sales, illustrating how even profitable firms can face repayment stress when cash inflows weaken.

Capital: structure and leverage

Capital reflects how the company balances debt and equity. Key metrics are Debt-to-Equity, Debt-to-Assets, and Net Debt/EBITDA. Higher leverage raises financial risk, but acceptable ranges are industry-specific: capital-intensive sectors may tolerate 2–3× EBITDA, while asset-light tech/retail often sit closer to 0.5–1.5×.

A practical example: L3Harris Technologies, a U.S. defense contractor, maintains moderate leverage with strong cash conversion, reinforcing its credit profile despite large-scale acquisitions.

Collateral: security and guarantees

Collateral is the lender’s safety net. Recoveries depend on the value and liquidity of pledged assets (property, receivables, equipment). Asset-light firms lack hard collateral and thus rely more on cash-flow quality and relationship history to mitigate risk.

Asset-light companies (e.g., software, consulting) rely more on cash flow and relationship capital rather than tangible assets, making consistent performance crucial to maintaining credit access.

Conditions: macro and industry context

Conditions cover both external factors (interest rates, regulations, economic cycles) and loan-specific purposes.

During tightening monetary cycles, higher financing costs can compress margins, while in recessionary or trade-sensitive sectors, declining demand directly raises default risk. For example, during 2022’s rate hikes, small exporters with floating-rate debt experienced significant declines in credit ratings due to rising interest expenses.

Financial perspective: reading credit signals in the statements

Effective credit analysis connects the three statements: the income statement (profitability), balance sheet (capital structure and asset quality), and cash flow statement (true repayment capacity).

Income statement: focus on revenue stability, margin trends, and the weight of non-recurring items. Persistent declines in gross or operating margins may indicate weakening competitiveness.

Balance sheet: examine asset quality and liability mix. High receivables or inventory build-ups can flag liquidity strain; heavy short-term debt raises refinancing risk.

Cash flow statement: the practical health check. Sustainable, positive operating cash flow that covers interest and capex signals solvency; strong accounting profits with chronically negative cash flow suggest poor earnings quality.

Useful cross-checks include Operating Cash Flow/Total Debt (coverage of principal from operations) and the persistence of negative free cash flow funded by external capital (a sign of structural vulnerability).

Beyond numbers: governance, transparency, and relationship capital

Creditworthiness extends beyond ratios. Governance quality, reporting transparency, competitive barriers, and banking relationships shape real-world risk. Policy-sensitive sectors (e.g., energy, real estate) exhibit higher cyclicality; tech and retail hinge on stable cash generation and customer retention. Stable leadership, prudent accounting, and timely disclosures build lender confidence. Long-standing cooperation and on-time performance often translate into better terms, a compounding of “relationship capital.”

At its core, credit is a form of deferred trust: banks lend to future behaviors and cash flows. Whether a firm deserves that trust depends on how it balances transparency, responsibility, and disciplined execution.

Conclusion

Credit analysis is not merely about numbers, it is about understanding how financial structure, behavioral consistency, and institutional trust interact. The 5C framework provides a structured map, yet effective analysts also recognize the fluid connections among its components: good character supports capital access, strong capacity reinforces collateral confidence, and favorable conditions amplify all others. Assessing creditworthiness is thus the art of finding order amid uncertainty, of determining whether a company can remain stable when markets turn turbulent.

Related posts on the SimTrade blog

About credit risk

▶ Jayati WALIA Credit risk

▶ Jayati WALIA Quantitative risk management

▶ Bijal GANDHI Credit Rating

About professional experiences

▶ Snehasish CHINARA My Apprenticeship Experience as Customer Finance & Credit Risk Analyst at Airbus

▶ Jayati WALIA My experience as a credit analyst at Amundi Asset Management

▶ Aamey MEHTA My experience as a credit analyst at Wells Fargo

Useful resources

Allianz Trade Determining Customer Creditworthiness

Emagia blog Assessing a Company’s Creditworthiness

About the author

The article was written in October 2025 by Dawn DENG (ESSEC Business School, Global Bachelor in Business Administration (GBBA), Smith-ESSEC Double Degree Program, 2024-2026).