Financial markets move with a constant rhythm, shaped by news, expectations, and the psychological impulses that influence investors every day. Prices advance, decline, accelerate suddenly, or pause without warning, and to the untrained observer this flow can seem arbitrary or even irrational. This can make it hard for investors to resist the urge of buying or selling their positions quickly.

This quote from Warren Buffett is a warning against it: markets reward those who remain disciplined and focused, while those who act hastily often pay a price for their impatience. The market is not hostile, but it is unforgiving towards impulsive behavior.

Patience allows an investor to benefit from the long-term effect of compounding, and from the natural tendency of solid businesses to grow over time, while impatience often leads to emotional decisions and unnecessary losses.

For students discovering finance, this idea is essential: long term thinking matters far more than reacting to every fluctuation, and why understanding the difference between noise and fundamentals is the foundation of intelligent investing.

About Warren Buffett and the context around this quote

Warren Buffett

Source : Forbes

Warren Buffett, often referred to as the Oracle of Omaha, is widely considered one of the most successful investors in history. His approach, inspired by Benjamin Graham and refined over decades, rests on a simple yet profound principle: invest in high quality businesses, pay a fair or attractive price, and allow time to do the work.

Buffett always emphasized the behavioral dimension of investing. He understood that markets are driven not only by numbers and earnings reports but also by the emotions of millions of individuals. His quote emerges from this observation. In his view, wealth tends to move from those who chase quick gains toward those who maintain a steady and patient perspective. Investors who panic in downturns or who jump rapidly from one trend to another often lose sight of the enduring value behind the companies they own, while patient investors remain focused on long term fundamentals and benefit accordingly.

The quote therefore illustrates a philosophy that has guided Buffett’s entire career: patience is not a passive posture but an active discipline that allows value to reveal itself over time.

Analysis of the quote

When Buffett says that the market transfers money from the impatient to the patient, he is not describing a mechanical rule but rather a behavioral reality. Impatient investors tend to react to fear, enthusiasm, fashionable narratives and short-term price movements. They buy when something is rising, they sell when it is falling, and they allow emotion to replace judgment.

Patient investors do the opposite: they base their decisions on analysis, intrinsic value, and long-term expectations. They endure volatility, because they understand that markets move in cycles, and that temporary declines often have little to do with the underlying quality of a business.

This distinction explains why timing the market is so difficult. Prices fluctuate for countless reasons, many of which are unrelated to value. Without patience, investors risk entering at euphoric peaks and exiting at fearful lows. With patience, they allow compounding, earnings growth, and valuation discipline to work slowly but steadily in their favor.

Financial concepts linked to the quote

To understand why the market favors the patient, we must look at the structural and psychological mechanics that reward those who remain calm.

Compounding: why time is your most important asset

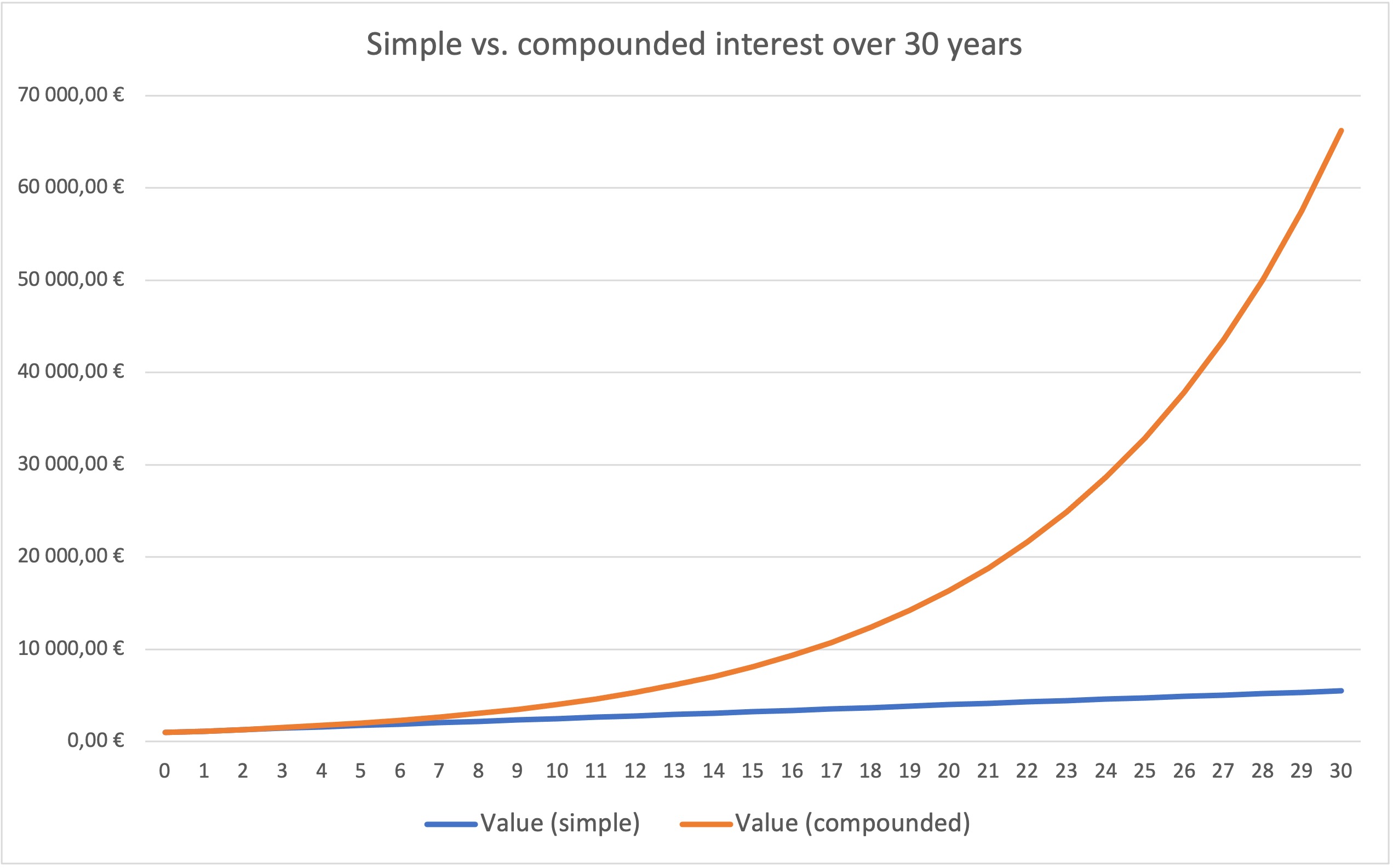

The most powerful tool available to an investor is compounding, a process where the returns on your capital begin to earn their own returns.

However, compounding is not a linear process; it is exponential. In the early stages, progress often feels slow and invisible, which is where many “impatient” investors make the mistake of quitting or changing strategies. To benefit from the “snowball effect,” an investor must possess the patience to endure these quiet early years so that the math can eventually reach its explosive later stages.

As you can see on this graph, compounded interest becomes trully impressive only after quite a long time.

To better understand the power of compounding, download this excel file and try to play around with the interest rate.

Every time an investor reacts to market volatility by selling or switching positions, they effectively stop their compounding clock. This “stop-and-go” approach is costly; by exiting the market out of fear, you don’t just avoid potential losses : you also forfeit the most explosive days of growth that often follow a downturn.

Since the market is nearly impossible to time perfectly, the most reliable path to wealth is not “timing” the market, but maximizing your time in the market.

The hidden cost of action bias

In nearly every aspect of life, effort correlates with reward: working harder, studying more, or practicing longer typically yields better results. However, the stock market operates under a different logic: it punishes excessive activity.

This counter-intuitive reality is best captured by the action bias, a powerful psychological urge to react to every market fluctuation or news headline by adjusting one’s portfolio.

The consequences are financially tangible : each impulsive trade incurs friction costs : brokerage fees, commissions, capital gains taxes… . Over time, these small deductions compound themselves into a significant drag on returns.

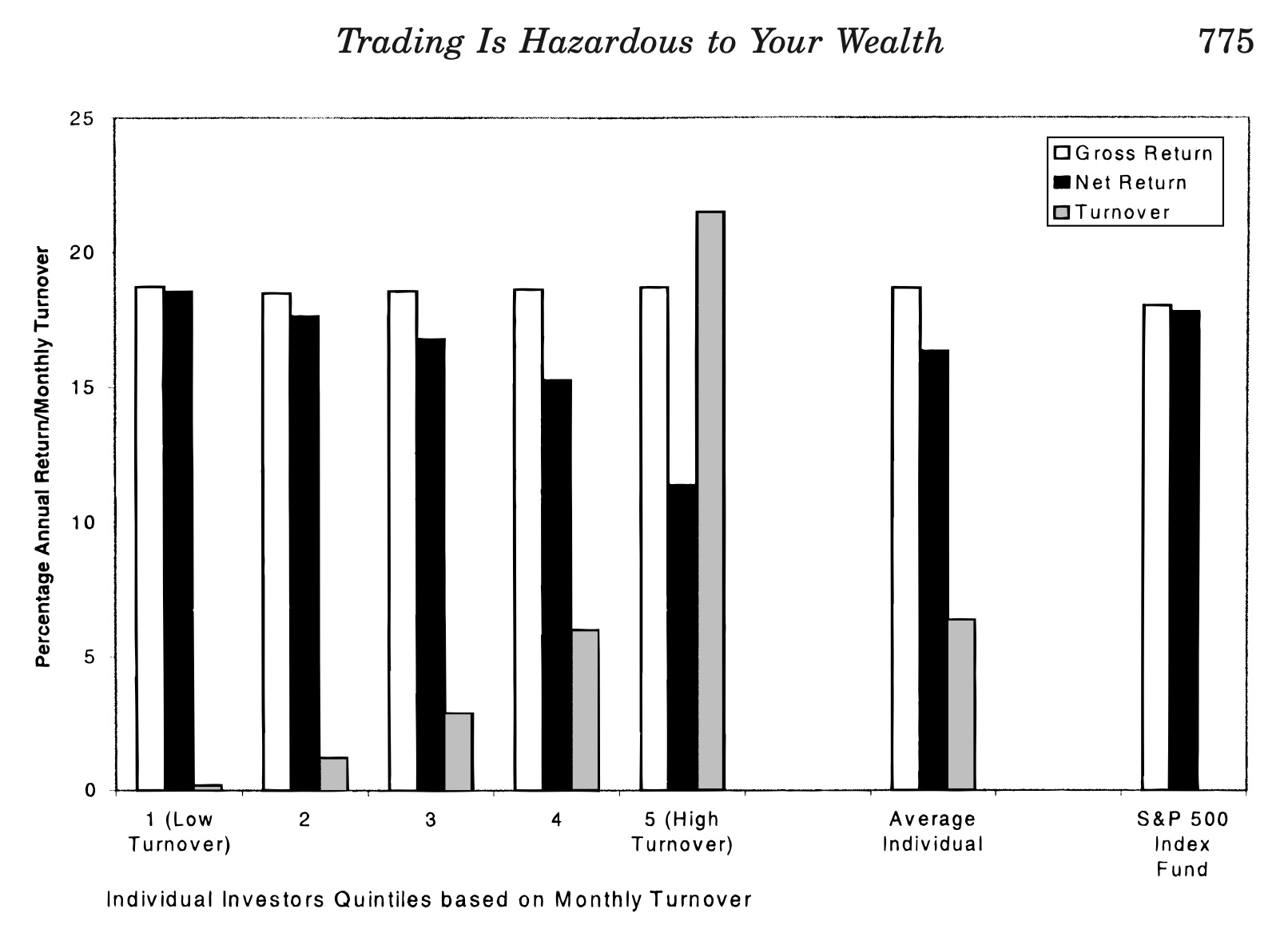

Studies, such as the landmark research by professors Brad Barber and Terrance Odean titled “Trading Is Hazardous to Your Wealth,” consistently show that the most active investors typically underperform simpler strategies. By analyzing thousands of accounts, they discovered that the most frequent traders earned significantly lower returns (by a margin of several percentage points) than those who simply stayed the course.

Source: Barber, B. M., & Odean, T. (2000).

This happens because attempts to “time” the market or avoid perceived risks often lead investors to miss crucial recovery periods. In doing so, they effectively turn off their compounding engine at precisely the wrong moment, proving that in the market, activity is often the enemy of performance.

Patience, therefore, isn’t just about waiting; it’s the profound discipline of knowing when to do nothing. It means resisting the innate human desire to act when faced with uncertainty, and trusting the long-term compounding process.

For students, understanding action bias is crucial. True control in investing often comes from emotional restraint, not constant intervention, and you should always remain calm when others panic.

Diversification: don’t put all your eggs in the same basket

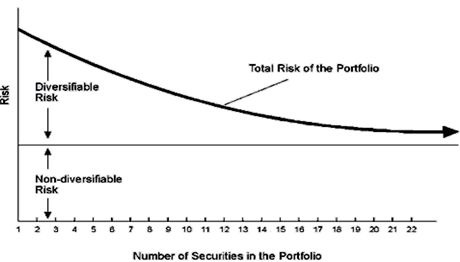

Patience is not merely a test of willpower; it also requires a properly structured portfolio, as it is far easier to remain calm when your entire financial future does not depend on a single outcome. This is where diversification (the practice of spreading investments across various companies, sectors, geographies, and asset classes) becomes a psychological necessity.

By ensuring you aren’t “putting all your eggs in one basket,” you replace the high-stakes anxiety of gambling with the steady reliability of participating in global economic growth.

Diversification therefore is important as an emotional safety net. If you concentrate your wealth into a single “trendy” stock and its price collapses, your natural instinct will be fear, which often leads to selling at the worst possible time. On the other hand, by diversifying your portfolio through an index fund, the failure of one company can be offset by the success of others. This limits the risk of a permanent loss of capital, and helps view market storms as temporary noise rather than a disaster.

Increasing the number of securities in a portfolio reduces unnecessary risk, limiting the risk of excessive fear for the investor

Increasing the number of securities in a portfolio reduces unnecessary risk, limiting the risk of excessive fear for the investor

The arithmetic of active management (Sharpe’s Law)

While Buffett focuses on the behavior of the investor, Nobel Laureate William Sharpe focuses on the math of the market. In his paper The Arithmetic of Active Management, Sharpe presents a simple, undeniable logic:

- Before costs, the average active manager must earn the same return as the market (the passive benchmark). The market return is the average of all manager’s returns, so it makes sense that the average manager’s return must be the market return.

- After costs (management fees, trading commissions, bid-ask spreads), the average active manager must underperform the average passive manager, because they have to bear higher costs.

This is not a matter of opinion, but a mathematical certainty. Passive investors hold the market at a very low cost, when active investors, as a group, hold the same stocks but pay high fees to analysts, traders, and managers who try to “beat” each other.

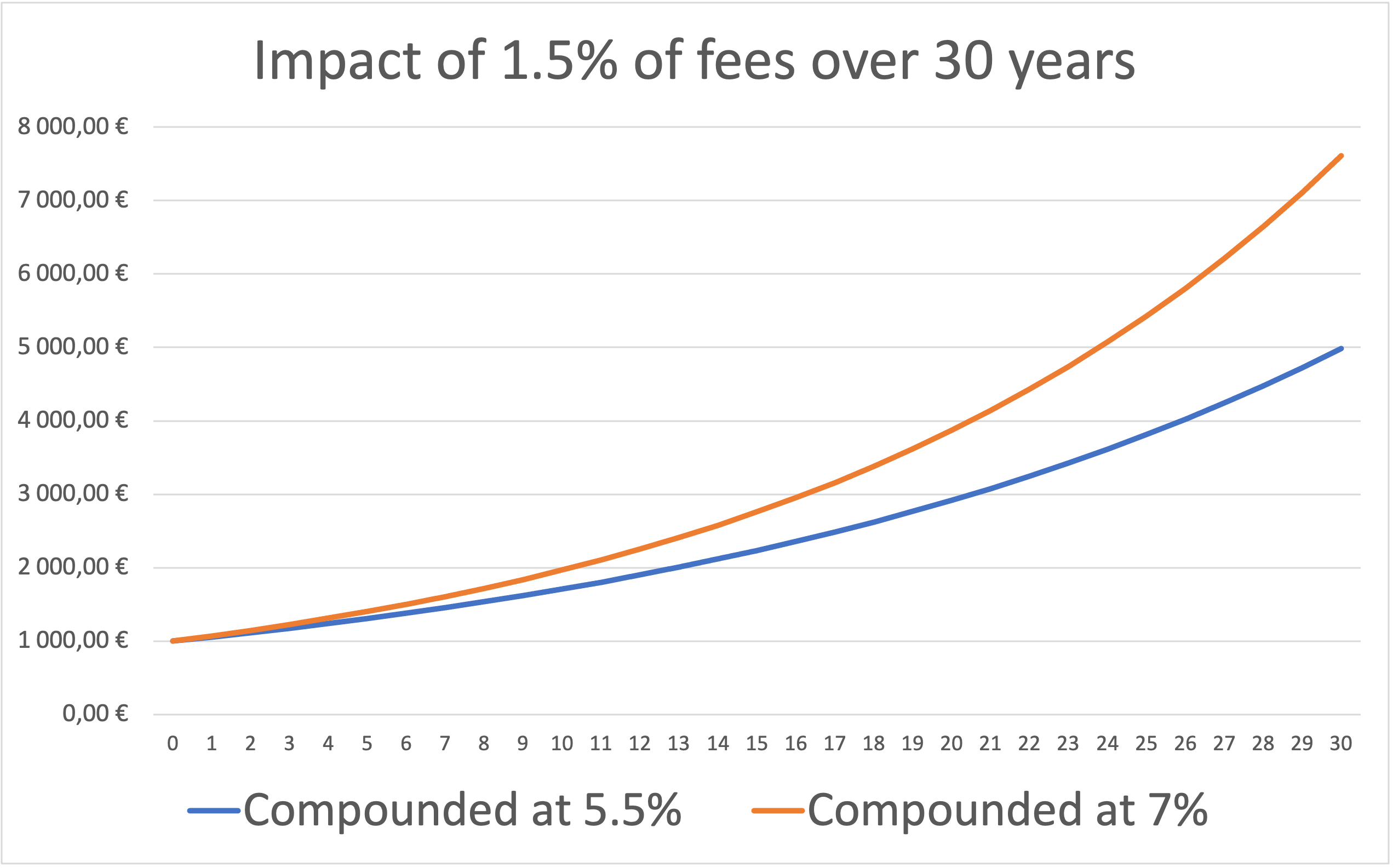

The impact of fees: the “silent killer” of compounding

Fees are the ultimate enemy of the patient investor. If the market returns 7% and an active fund charges 1.5% in fees, the investor only keeps 5.5% every year.

But over 30 years, that 1.5% difference doesn’t just reduce your return by 1.5%: that lost money is never allowed to compound, and because of this, your final wealth will by much lower.

As Sharpe argues, active management is a “zero-sum game” before costs, but a “negative-sum game” after costs for the participants involved.

My opinion on the quote

I believe this quote captures one of the most essential truths in investing: behaviour matters just as much as analysis. Patience is not a simple virtue, it is a true competitive advantage. In a world where information circulates instantly and where impatience is encouraged by constant market noise, choosing to remain calm and long term oriented becomes a rare and valuable discipline.

Buffet’s perspective also helps reinterpret market volatility. Rather than seeing it as a threat, patient investors see it as an opportunity to accumulate quality assets at reasonable prices. Impatient investors, on the contrary, allow volatility to dictate their actions, which often leads to regret. For students, understanding this psychological dimension is essential because it prepares them for the realities of financial markets where noise is constant and conviction must be earned.

Why you should care about this quote

This quote is about avoiding impulsive reactions to short term movements, being able to distinguish between emotion and information, and to appreciate the slow and steady nature of compounding. It emphasizes the importance of discipline, valuation, and long term thinking, and it reveals why the greatest investors often seem remarkably calm in the face of market turbulence.

Ultimately, Buffett’s quote reminds us that markets reward patience not by coincidence but by design. They favor those who stay focused while others are distracted, those who think in years rather than in minutes, and those who allow value to express itself with time. For any student aspiring to navigate markets with intelligence and serenity, this is a principle worth integrating into your financial education.

Related posts

Famous quotes

▶ Hadrien PUCHE “Price is what you pay, value is what you get” – Warren Buffett

▶ Hadrien PUCHE “Patience is bitter, but its fruit is sweet.” – Aristotle

▶ Hadrien PUCHE “The big money is not in the buying and selling, but in the waiting.” – Charlie Munger

Asset management

▶ Youssef LOURAOUI Active investing

▶ Youssef LOURAOUI Passive investing

Useful resources

Academic research

Barber, B. M. & Odean, T. (2000) Trading Is Hazardous to Your Wealth: The Common Stock Investment Performance of Individual Investors. The Journal of Finance, 55(2), 773–806.

Barberis, N. & Thaler, R. (2003) A Survey of Behavioral Finance. Handbook of the Economics of Finance, 1B, 1053–1128.

Odean, T. (1999). Do Investors Trade Too Much? The American Economic Review, 89(5), 1279–1298.

Sharpe, William F. (1991). The Arithmetic of Active Management. Financial Analysts Journal, 47(1), 7–9.

Business resources

Buffett W.E. Berkshire Hathaway Shareholder Letters Omaha, NE: Berkshire Hathaway Inc.

Schroeder A. (2008) The Snowball: Warren Buffett and the Business of Life. New York: Bantam Books, 2008.

About the Author

This article was written in February 2026 by Hadrien PUCHE (ESSEC Business School, Grande École Program, Master in Management, 2023-2027).

▶ Discover all posts by Hadrien PUCHE