In an era dominated by instant trading for individuals, high-frequency trading firms, ever-faster market infrastructures, and social-media-driven market narratives, patience has become an underrated virtue.

In this article, Hadrien PUCHE (ESSEC Business School, Grande École Program, Master in Management, 2023-2027) comments on Charlie Munger’s famous quote about the role of patience and discipline in long-term investing, and what it teaches us about the power of compounding, temperament, and time.

About Charlie Munger

Charlie Munger (1924–2023) was the long-time vice chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, and Warren Buffett’s closest business partner for over 50 years. Munger profoundly influenced Buffett’s philosophy, steering him toward buying high-quality businesses and holding them for the long run.

Munger’s wisdom combined principles from psychology, economics, and philosophy to form a timeless view of markets and human behavior.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

About the quote

“The big money is not in the buying and selling, but in the waiting.”

This quote is one of Charlie Munger’s most enduring lessons, though its origins date back to the 1923 classic Reminiscences of a Stock Operator by Jesse Livermore. Munger adopted and popularized this wisdom throughout his career, most notably during the Berkshire Hathaway annual shareholder meetings, to explain the firm’s extraordinary success.

The quote encapsulates the essence of long-term investing: wealth is not built through frequent market timing, but through the quiet power of patience and compounding. Munger and Buffett repeatedly emphasized that the most successful investors are not those who move the fastest, but those who possess the “temperament” to sit still when the rest of the market is acting impulsively.

Ultimately, this principle suggests that time, rather than timing, is the real driver of wealth creation. In Munger’s view, “waiting” is an active strategy. It is the disciplined choice to let your initial thesis play out without the interference of market noise or emotional reactions.

Analysis of the quote

This quote highlights a key principle of investing: activity is not the same as value creation. Many investors confuse motion with progress, feeling the urge to trade constantly in response to news, trends, or short-term price fluctuations.

Munger’s philosophy reminds us that wealth is not “generated” by the act of trading; it is accumulated by letting compounding do its work, a process that rewards patience and conviction far more than speed. Charlie Munger’s observation, “The first rule of compounding is to never interrupt it unnecessarily,” distills decades of investing wisdom into a single principle: long-term wealth creation depends less on brilliance than on consistency and emotional endurance.

Every time an investor exits a position due to short-term fear or a desire to “lock in” small gains, they “reset” the clock and sacrifice the exponential growth that occurs in the final years of a holding period. Furthermore, frequent activity creates “leakage” through trading costs and taxes, which act as a constant drag on returns.

In essence, Munger’s rule is a call for consistency over cleverness, emphasizing that compounding rewards time and temperament, qualities far rarer and more valuable than momentary flashes of insight.

Financial concepts related to the quote

I present below three financial concepts: the power of compounding, opportunity cost and value of inactivity, and the patience premium of investor behavior.

The Power of Compounding

Compounding is the process by which returns themselves begin to generate further returns: a self-reinforcing cycle of growth. Its effect is exponential rather than linear: small, steady gains, that accumulate dramatically over time.

For instance, at a 10% annual return, an investment of 100 grows to 110 after one year, 259 after ten years, and 1,745 after thirty years. The formula for the future value Vf is:

Where ρ (rho) is the interest rate and n is the number of times that interest is compounded every year. The key variable is time (t): the longer the compounding process continues uninterrupted, the greater the growth. Interruptions through withdrawals or frequent trading can significantly reduce the ultimate value of the investment.

Opportunity Cost and the value of inactivity

In behavioral and financial terms, opportunity cost is what one sacrifices by choosing one action over another. Many investors mistakenly equate activity with progress, yet frequent transactions often lead to higher costs, taxes, and emotional errors. As Buffett and Munger emphasize, strategic inactivity (allowing quality investments to compound) is often the most effective decision one can make.

The “Goalkeeper Syndrome”: A Lesson from the Pitch

This tendency to favor motion over stillness is driven by action bias. A study by Bar-Eli et al. (2007) on elite soccer goalkeepers found that while goalkeepers have the highest probability of stopping a penalty by staying in the center of the goal, they only do so 6.3% of the time. In over 93% of cases, they dive to the left or right.

This “Goalkeeper Syndrome” is best explained by Daniel Kahneman’s Norm Theory (Thinking, Fast and Slow, 2011). Kahneman demonstrates that humans feel more intense regret when a bad outcome results from an action than from an inaction—unless the action is the norm.

In the goalkeeper’s case, jumping is the social norm. If a goal is scored while the keeper stands still, they appear to have “done nothing,” which is socially and emotionally harder to bear. If they dive and miss, they have “tried.” For investors, this creates a dangerous paradox. In the investment industry, “activity” is often the norm. A fund manager who does nothing during a market shift risks being seen as lazy or incompetent. By “diving” into a new trade, they protect themselves from the intense regret of being wrong while being inactive.

Recognizing this bias is essential for any finance professional. True discipline lies in knowing when to act, and having the courage to stay in the center of the net when everyone else is jumping.

The Patience Premium and Investor Behavior

Behavioral finance demonstrates that human psychology often works against long-term success. Biases like overconfidence, loss aversion, and herd behavior push investors to buy high and sell low. The ability to stay rational when others panic — to maintain conviction in one’s analysis rather than react to market noise — creates a powerful advantage.

This discipline produces what can be called a patience premium: higher long-term returns earned simply by avoiding costly mistakes. As Warren Buffett summarized, “The stock market is a device for transferring money from the impatient to the patient.”

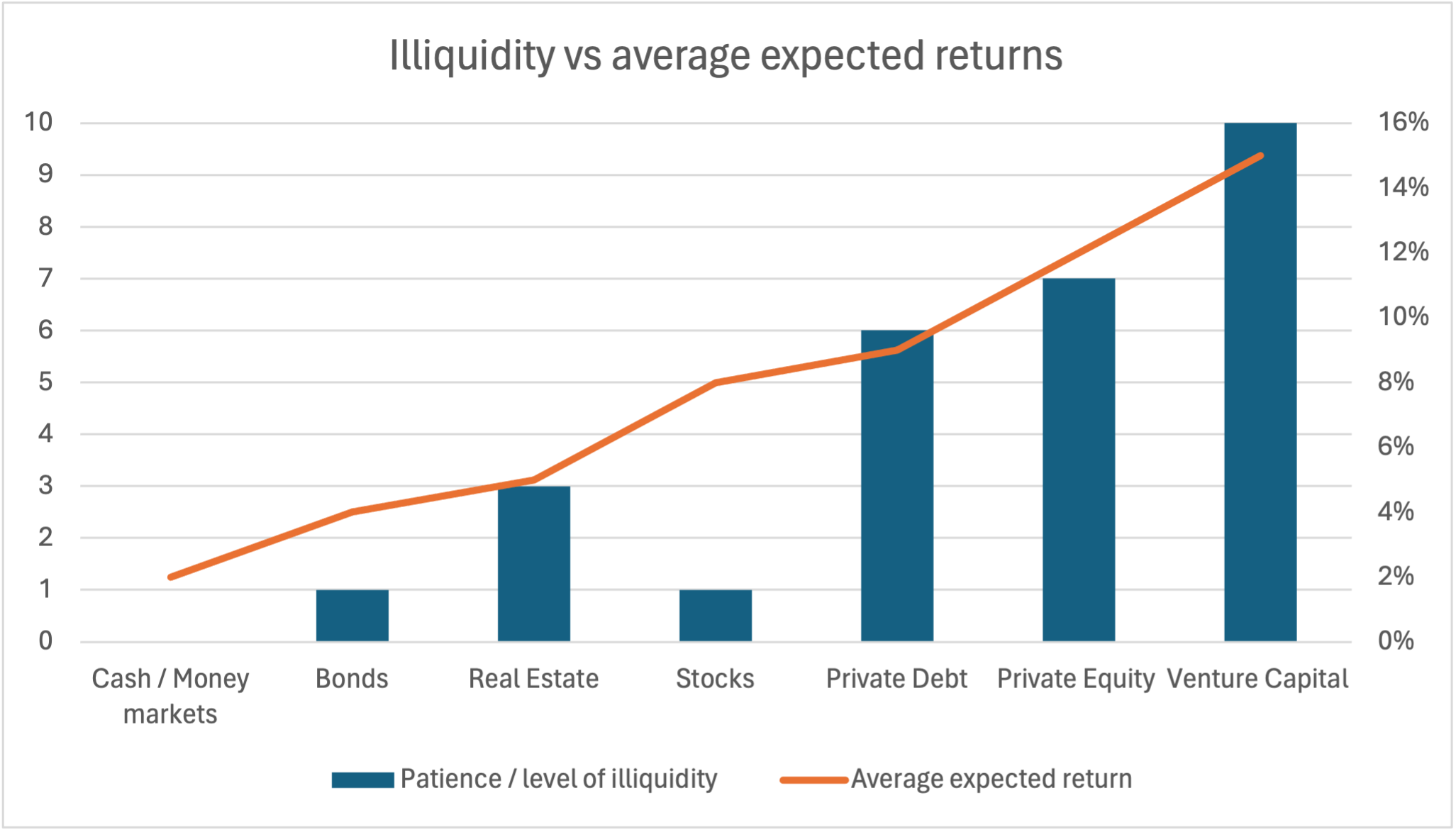

Private equity provides a practical illustration of the patience premium. Investments in private companies are typically illiquid for many years, forcing investors to maintain a long-term perspective. This “forced patience” comes with a reward: private equity funds historically deliver higher returns than public markets, reflecting both the illiquidity premium and the benefits of disciplined, long-term value creation.

In general, more illiquid investments offer higher expected returns, as investors are compensated for the additional illiquidity risk. Note: Values are illustrative.

Beyond the financial premium, illiquidity serves as a vital behavioral guardrail. In public markets, the ability to sell an asset instantly makes it far easier to succumb to panic during market turbulence. You cannot “panic sell” an asset that you cannot sell quickly. By removing the option for impulsive exits, illiquid structures protect investors from their own emotional reactions, ensuring that compounding is never interrupted unnecessarily.

My opinion about this quote

I believe this quote captures one of the hardest truths in investing: sometimes the most profitable action is to do nothing. In today’s world of trading apps, meme stocks, and 24-hour market news, patience feels almost countercultural. Investors are constantly nudged to act, reacting to every headline or social media hype. Yet, this very activity often erodes long-term returns.

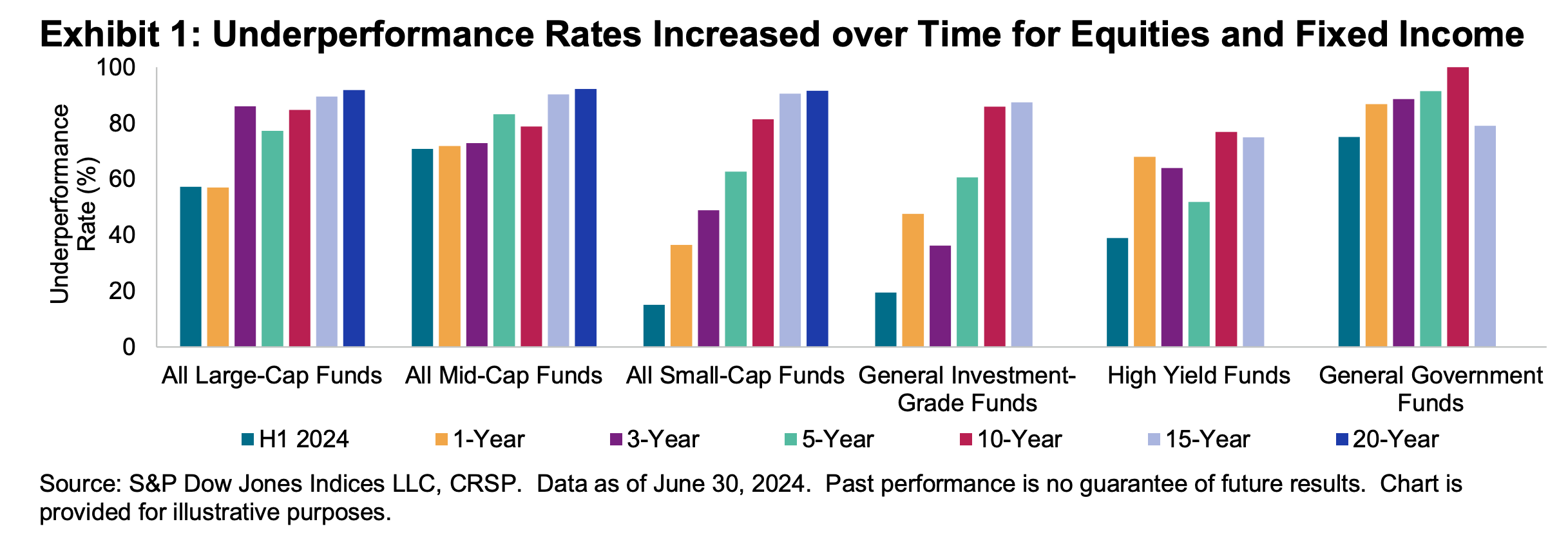

One concrete way to see this principle in action is through passive investing. Actively managed funds exist with the goal of outperforming their benchmark indexes, yet studies like SPIVA (S&P Indices Versus Active) show that most fail to do so over long periods. For instance, over 10-year periods, roughly 80% of U.S. equity funds underperformed the S&P 500 index.

This SPIVA graph illustrates that most actively managed funds underperform their benchmark index over the long term, highlighting the advantage of passive investing.

However, this debate between active and passive management leads us to a fascinating theoretical tension: the Grossman-Stiglitz Paradox. If every investor followed the “sweet fruit” of passive investing because it is statistically superior, the market would cease to function properly and make active investment worth it again.

The paradox, formulated by Sanford Grossman and Joseph Stiglitz in 1980, suggests that markets cannot be perfectly efficient. If a market were perfectly efficient (meaning all information is already reflected in the price), no one would have an incentive to spend time uncovering new information. But if no one uncovers information, the market becomes inefficient. Therefore, the market must remain “efficiently inefficient”: it requires active managers to do the “bitter” work of research, even if they often fail to beat the index, so that passive investors can enjoy the “sweet” ride of a mostly accurate market price.

Yet, the lesson is clear: staying invested in a broadly diversified index often beats trying to “time” the market. The patient investor harnesses compounding without the friction of trading costs, taxes, and emotional mistakes. As Munger famously noted, “the big money is not in the buying and selling, but in the waiting.” It’s not about inactivity for its own sake; it’s about informed, disciplined inactivity.

Why should you be interested in this post?

Beyond investing, this quote is about cultivating a mindset of patience, discipline and rational thinking that can separate successful individuals from the crowd. Mastering the art of waiting will give you an edge, no matter which industry you desire to work in.

Careers, skills, and personal growth all compound like investments; building expertise takes time. Quick wins may feel gratifying, but long-term impact comes to those who embrace patience and persist through the quiet, unglamorous work that others sometimes avoid.

Related posts

▶ Hadrien PUCHE “The stock market is filled with individuals who know the price of everything, but the value of nothing.” – Philip Fisher.

▶ Hadrien PUCHE “Most people overestimate what they can do in a year and underestimate what they can do in ten.” – Bill Gates

▶ Hadrien PUCHE “Patience is bitter, but its fruit is sweet.” – Aristotle

Useful resources

Berkshire Hathaway’s website: www.berkshirehathaway.com

Munger, Charlie. Poor Charlie’s Almanack, 2005.

Buffett, Warren. Berkshire Hathaway Shareholder Letters.

Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking, Fast and Slow, 2011. (especially Chapter 32 on regret and norm theory).

Bar-Eli, M., Azar, O. H., Ritov, I., Keidar-Levin, Y., & Schein, G. (2007) Action bias among elite soccer goalkeepers: The case of penalty kicks. Journal of Economic Psychology, 28(5), 606-621.

About the Author

This article was written in January 2026 by Hadrien PUCHE (ESSEC Business School, Grande École Program, Master in Management, 2023-2027).

▶ Discover all articles by Hadrien PUCHE