In financial markets, everyone wants to be right. The temptation to make accurate predictions, about earnings, interest rates, recessions, or stock prices, is universal. But as George Soros reminds us, accuracy alone is meaningless. What truly matters is how much you profit when you’re right, and how much you lose when you’re wrong.

This quote challenges one of the deepest misconceptions in trading: the belief that success depends on predicting the future. In reality, trading success mostly depends on risk management, position sizing, and the discipline to adjust when the market proves you wrong.

About George Soros

George Soros

Source: EU

George Soros (born in 1930) is a Hungarian-American investor and philanthropist. He founded Soros Fund Management, a global macro hedge fund known for making large, directional bets across currencies, bonds, equities, and commodities.

Soros became globally famous in 1992 when he “broke the Bank of England” by shorting the British pound, a trade widely reported to have earned over $1 billion.

The European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) was created to stabilize European currencies ahead of the future monetary union by keeping exchange rates within narrow fluctuation bands. When the UK joined, it agreed to maintain the pound within this band, but entered at a rate that many considered overvalued.

Seeing this imbalance, George Soros spent months building a large short position against the pound. On “Black Wednesday” in 1992, the British government failed to defend the currency through interest-rate hikes and interventions, forcing a devaluation. Soros reportedly earned over $1 billion and became known as “the man who broke the Bank of England.”

Not all of Soros’s trades were successful. In 2016, he reportedly lost close to $1 billion after wrongly predicting that markets would fall following Donald Trump’s election.

Beyond trading, Soros developed the theory of reflexivity, which argues that markets are shaped by feedback loops between perceptions and fundamentals. His philosophy emphasizes uncertainty, adaptability, and the psychological drivers behind market behavior.

The context behind this Quote

This quote is not actually from Soros. It comes from Stanley Druckenmiller—Soros’s former chief strategist—in The New Market Wizards (1994). Druckenmiller explains that the most important lesson he learned from Soros was not the importance of being right, but of structuring trades so that being right pays off and being wrong costs little.

The quote therefore reflects Soros’s investment philosophy: markets cannot be predicted with certainty, so success depends more on managing risk than on forecasting.

This mindset is foundational to modern risk management and a key reason Soros is considered one of the most influential investors of the past century.

Analysis of the Quote

The quote captures three essential ideas:

- asymmetric returns

- risk management

- intelligent position sizing

Being right doesn’t matter unless it pays. For example, even if you forecast Nvidia’s earnings perfectly, you may still fail to profit because:

- You may not have any position.

- Your position may be too small.

- The market may behave irrationally.

- Losses on other trades may outweigh this one win.

This is the essence of risk management: structuring positions so that winners meaningfully contribute to performance while losers remain contained.

Let’s introduce three key financial ideas that relate to this quote.

1. Diversification and Position Timing

Even if your analysis is correct, the market might not react as expected, or not at the right time. This is where the distinction between trading and investing matters.

Soros’s quote speaks the language of trading: position sizing, timing, and controlling downside on each bet.

Investing, by contrast, relies less on precise timing and more on diversification, which reduces exposure to unpredictable events and smooths returns across different regimes.

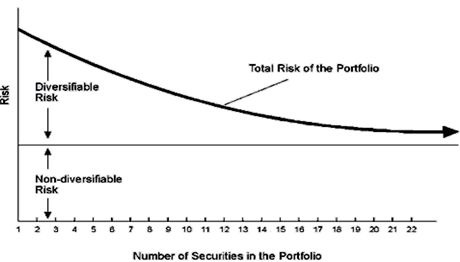

Mathematically, diversification lowers portfolio variance because asset returns are imperfectly correlated. Even when individual positions behave unpredictably, a well-constructed portfolio can achieve far better risk-adjusted results than any single trade. In that sense, diversification plays a similar role for investors as stop-losses and disciplined position sizing do for traders: it manages the impact of being wrong.

The following graph illustrates how adding more independent positions reduces overall portfolio risk.

2. Avoid cutting winners to reinforce losers

This behavioral trap affects most investors. Soros’s approach is the opposite:

- cut losing positions quickly

- let winners run

Yet, due to loss aversion (as formalized by Kahneman & Tversky (1979) in Prospect Theory), investors often do the reverse:

- sell winners too early

- hold losers too long

This pattern is well-documented in the literature. Shefrin & Statman (1985) termed it the disposition effect: the systematic tendency to “sell winners too early and ride losers too long.” The emotional discomfort of realizing a loss often outweighs the rational need to exit a bad position.

Momentum works partly for this reason. Rising prices attract reluctant investors who delayed selling their winners, amplifying trends; meanwhile, stubbornly held losers can drift downward for longer than fundamentals alone would justify.

3. Quantitative trading: the power of averaging out

Quantitative trading is built on making many small, systematic bets with a positive expected value. The goal is not to win every trade, but to win more (or bigger) on average.

This is the practical application of the idea that:

- being right occasionally with large wins

is more valuable than - being right frequently with small gains.

This also echoes Jesse Livermore’s famous line: “The market is never wrong, only opinions are.” (link)

My view on this quote

One limitation of Soros’s statement is that it implicitly assumes the reader is an active trader. In reality, today’s markets are dominated by algorithms, quantitative models, and high-frequency strategies, an environment in which most individuals are unlikely to outperform professional traders. For traders, Soros’s point is straightforward: you will often be wrong, so what matters is how you size positions and manage risk when you are.

At a literal level, the quote may also seem paradoxical: you cannot know in advance which trades will be winners or losers. But the message isn’t about prediction, it’s about discipline.

This distinction becomes especially clear when you contrast trading with investing.

- Traders live in a world of short-term uncertainty and constant position adjustments, where the asymmetry between gains and losses determines survival.

- Investors, on the other hand, think in years, not minutes. They rely less on timing and more on letting fundamentals and compounding work over time. For them, the “how much you lose when you’re wrong” part translates into diversification, staying invested, and avoiding irreversible mistakes rather than optimizing each individual decision.

Seen this way, Soros’s line applies to both groups, just at different scales: traders manage outcomes trade by trade; investors manage them across decades. Either way, the principle holds: success depends less on being right and more on controlling the cost of being wrong.

Why should you care about this quote ?

The lesson is not about predicting markets or mastering sophisticated position sizing. The deeper message is:

- Don’t rely on being right.

- Structure your trades so that mistakes are limited and successes compound.

A diversified ETF strategy naturally achieves this.

In cap-weighted indices:

- winners grow in weight

- losers shrink, limiting their impact

- the portfolio trends with long-term market growth

This simple, robust approach aligns with Soros’s philosophy: control the downside, let the upside work.

Related Posts

- All posts about Quotes

- “The market is never wrong, only opinions are.”

- Portrait of George Soros: a famous investor

Useful Resources

- Soros, George (1987). The Alchemy of Finance. Soros explains reflexivity, asymmetry of payoff, and his macro-trading framework.

- Schwager, Jack (1994). The New Market Wizards. Contains Stanley Druckenmiller’s interview where the famous quote originates.

- The Disposition to Sell Winners Too Early and Ride Losers Too Long: Theory and Evidence — Hersh Shefrin & Meir Statman (Journal of Finance, 1985, 40(3), 777–790).

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–291.

To learn more about Soros’s famous 1992 British pound trade:

- Eichengreen, Barry & Wyplosz, Charles (1993). “The Unstable EMS.” A leading academic analysis of why the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) became vulnerable and how the 1992 crisis unfolded.

- Bank of England (1993). Report on the Withdrawal of Sterling from the ERM. Official institutional account of the events surrounding Black Wednesday.

About the Author

This article was written in 2025 by Hadrien Puche (ESSEC, Grande École Program, Master in Management – 2023–2027).