The Gold Standard

In this article, Nithisha CHALLA (ESSEC Business School, Grande Ecole Program – Master in Management (MiM), 2021-2024) explores the origins, implementation, and eventual decline of the gold standard, leading to the establishment of the Bretton Woods system, which redefined global financial stability in the post-World War II era.

Introduction

The concept of using gold as a basis for currency emerged in the early 19th century, aiming to provide a universally accepted standard of value for trade and to reduce inflation. Countries agreed that their paper currency could be exchanged for a fixed amount of gold, which limited the amount of money governments could issue, thus preventing inflation.

The United Kingdom was one of the earliest adopters, establishing the gold standard formally in 1821. The system allowed Britain to stabilize its currency and promote global trade, reinforcing its position as a leading global economic power. This model inspired other countries to adopt similar standards. By the late 19th century, several countries, including the United States (1900), Germany (1873), and France (1873), adopted the gold standard. The U.S. had been on a de facto gold standard since 1879 and later officially adopted the gold standard in 1900 with the Gold Standard Act, and the practice became increasingly popular as global trade expanded.

The Gold Standard’s Role in Economic Stability

Some key features of the classical gold standard are exchange rates, price stability, and discipline in monetary policy.

Stabilizing Exchange Rates

One of the primary benefits of the gold standard was stable exchange rates, which encouraged international trade and investment. By fixing the value of their currencies to a certain amount of gold, countries reduced currency fluctuation, making trade more predictable.

Preventing Inflation

Price stability (low inflation) was demanded since governments could only print as much currency as their gold reserves permitted. The gold standard limited excessive money printing and helped prevent inflation.

International Trust and Trade

The gold standard fostered trust among trading nations because gold-backed currencies reduced the risk of devaluation. Trade partners knew they were dealing in stable, reliable currencies.

Countries that Opted Out of the Gold Standard

According to an article published by Cooper, R Dornbusch and Hall (1982), until the late 19th century most countries were on a bimetallic standard, interspersed with occasional periods of inconvertible paper (as in the United States in the 1780s and the 1862-78 period, or Britain from 1797 to 1821). Some countries, such as China and Mexico, were only based on silver until the twentieth century. Holland and Belgium even switched from bimetallism to silver alone in 1850 on the grounds (following the California gold discoveries in 1848) that gold was too unstable to provide the basis for the currency. The United States adopted a de facto gold standard with the resumption of specie payment on the Civil War greenbacks in 1879 (some would say it was formal since the standard silver dollar was dropped from the coinage in the “crime of 1873”); it moved formally with the Gold Standard Act of 1900.

Though several countries opted for the classical gold standard, there were still many countries who chose to opt out because of economic challenges:

- Economic Challenges and Opt-Outs: Some countries struggled to adopt the gold standard, especially those with weaker economies or limited gold reserves. For example, several Latin American countries and parts of Eastern Europe either delayed adopting the standard or abandoned it after a short period due to limited gold resources.

- Flexibility vs. Stability Debate: Countries facing frequent economic crises found the gold standard too restrictive. By adhering to a strict gold-based system, governments had less flexibility to respond to economic downturns, which later became a crucial issue in the Great Depression.

The Great Depression and the Decline of the Gold Standard

During the Great Depression (1929–1939), many countries faced extreme economic challenges. The rigid nature of the gold standard prevented governments from increasing the money supply to stimulate growth, worsening the economic crisis.

In response, several major economies, including the United Kingdom (1931) and the United States (1933 under President Franklin D. Roosevelt), abandoned the gold standard to regain control over their monetary policies. This allowed them to inject liquidity into the economy, stimulating growth and reducing unemployment. The gold standard was briefly reinstated in a modified form, known as the “gold exchange standard,” but it was ultimately unsustainable in the post-Depression global economy.

Transition from the Gold Standard to the Bretton Woods System

After World War II, the world needed a new financial system to prevent the economic instability that had contributed to the Great Depression. The gold standard was no longer viable, but there was still a need for a stable international currency framework.

In 1944, delegates from 44 nations gathered in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, to establish a new global monetary system. The Bretton Woods system introduced a modified form of the gold standard where the U.S. dollar became the central reserve currency, convertible to gold at a fixed rate of $35 per ounce.

Some key features of the Bretton Woods system were:

- U.S. Dollar as the Global Reserve: Countries agreed to peg their currencies to the U.S. dollar, and in turn, the dollar was backed by gold. This established the U.S. as the central player in global finance.

- International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank: The Bretton Woods conference also established the IMF and the World Bank to oversee exchange rates, provide financial assistance, and promote economic development.

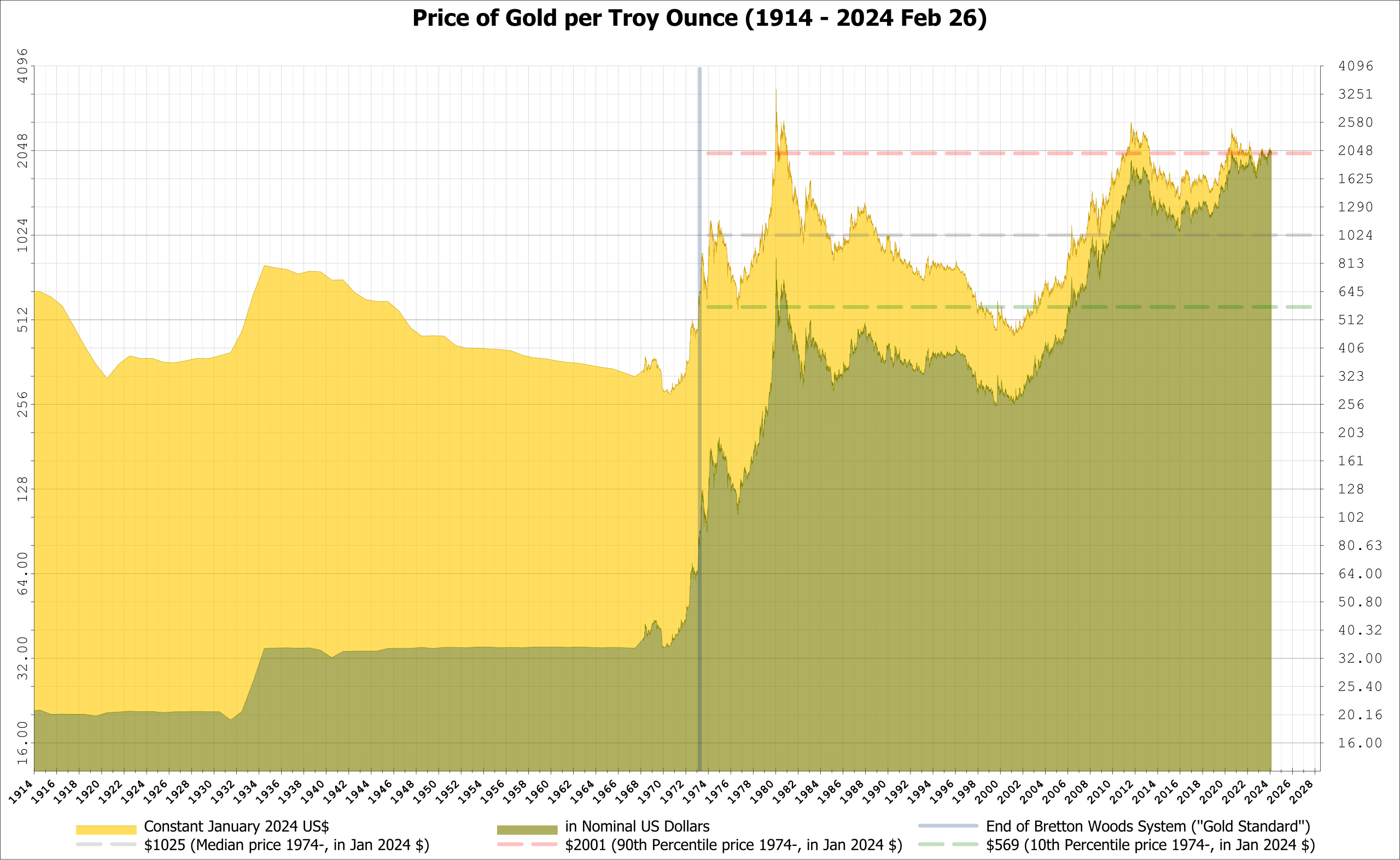

The figure below shows the dollar conversion price to gold bullion for the period 1914-2024.

Dollar conversion price to gold bullion for the period 1914-2024

Source: Wikipedia

By the 1960s, the U.S. began running significant trade deficits, and its gold reserves dwindled as foreign governments exchanged dollars for gold. The U.S. could no longer sustain the gold-dollar convertibility at the set rate of $35 per ounce. In 1971, President Richard Nixon announced the end of dollar convertibility to gold, effectively ending the Bretton Woods system. This decision led to a floating exchange rate system, where currencies were no longer tied to gold but fluctuated based on market forces.

Conclusion

The gold standard played a vital role in creating a stable economic environment and promoting international trade in the 19th and early 20th centuries. However, its rigidity limited countries’ ability to respond to economic crises, eventually leading to its abandonment during the Great Depression. The Bretton Woods system provided a middle ground, establishing a dollar-based standard that aimed to maintain stability while allowing more flexibility. However, as global economies evolved, even this system proved unsustainable, paving the way for today’s floating exchange rate regime.

Why should I be interested in this post?

Gold has been a key financial asset for centuries, acting as a store of value, a hedge against inflation, and a safe-haven asset during economic crises. Understanding its investment options helps students grasp fundamental market dynamics and investor behavior, especially during periods of economic uncertainty.

Related posts on the SimTrade blog

▶ Nithisha CHALLA History of Gold

▶ Nithisha CHALLA Gold resources in the world

Useful resources

Academic research

Cooper RN, R Dornbusch, RE Hall (1982) The Gold Standard: Historical Facts and Future Prospects, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1982(1): 1-56.

Business

World gold council The Bretton Woods System

Federal Reserve History Creation of the Bretton Woods System

Other

Wikipedia Gold

Wikipedia Bretton Woods system

About the author

The article was written in November 2024 by Nithisha CHALLA (ESSEC Business School, Grande Ecole Program – Master in Management (MiM), 2021-2024).